Compiled by Adam Jones, Ph.D.

Research Associate, Department of Political Science

University of British Columbia

C472 - 1866 Main Mall

Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6T 1Z1

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

For more on gender-selective atrocities against men,

including extensive Kosovo materials, see the Gender Page

of this website.

Australia estimates that up to 1,000 people were killed in East Timor during the violence after the United Nations vote.

Foreign Affairs Minister Alexander Downer gave a death toll estimate of between 500 and 1,000 people.

Speaking to the National Press Club in Canberra, Mr Downer discounted allegations that Indonesian forces dumped thousands of bodies at sea.

"Even if they were dumped at sea, the bodies would have washed up," he said.

"They clearly weren't dumping at sea tens of thousands of bodies with concrete around their necks so the bodies would stay under water.

"Simply the mechanics of that would be impossible, so this is in any case an assessment that we would make and the UN would make.

"Look, believe me if between 500 and 1,000 people died that's a terrible thing - that's a lot of people to die, but on the other hand it's not tens of thousands." [...]

[Comment: Okay, let me get this straight. Interfet has found over 100 bodies without even looking (I have seen no update for two weeks). The East Timor Human Rights Centre has found nearly 400 in Dili alone. At a minimum, 200-300 people are known to have died at Suai; dozens of the victims are turning up in mass graves in West Timor. U.S. and Australian intelligence sources report repeated dumpings of corpses at sea. More than 100 bodies have been reported washed up on beaches, on both coasts (I have seen no update for two weeks). Eyewitness testimony from Maliana speaks of more than 40 people (men) dying in an hour of public executions in one small town. Many tens of thousands of Timorese, at a minimum, are still unaccounted for. And the Minister of Foreign Affairs is estimating between 500 and 1,000 killed? He is living in la-la land.]

A five-member UN mission has completed nine days of investigation into allegations of atrocities in East Timor, but has declined to say whether an international tribunal to try those responsible will be necessary.

Costa Rican jurist Sonia Picado, who led the team, says the commission had listened to more than 160 witnesses and met various East Timorese leaders during the nine days they stayed in East Timor.

Militias, supported by Indonesian security forces, waged a campaign of murder, arson and forced deportation after the East Timorese voted for independence in August.

The task of the UN commission of inquiry is to substantiate claims of atrocities made by refugees.

Many have maintained the Indonesian Army orchestrated the militia rampage.

[Comment: Five people. Nine days.]

COMPERE: Amnesty International's increasing the pressure on the Australian Government to hand over intelligence information on human rights' abuses in East Timor. The United Nations has already set up a special Commission of Inquiry to process any evidence. This afternoon, Amnesty representatives met the Foreign Affairs Minister, Alexander Downer, to seek guarantees that Australia will co-operate.

Amnesty National Director, Kate Gilmore, told Sally Sara in Canberra that the government is promising to live up to international standards.

KATE GILMORE: Well, it's significant that this affirmation is given. As to what it means in practice, none of us quite knows. The government will reserve its right to withhold information if it thinks it threatens Australian security.

From Amnesty International's point of view we think due justice with respect to human rights' violations has to be first order priority. We want as much transparency in that process, and we want the region's governments, including Australia, to fully co-operate. How can we be assured of that when the government reserves its right to withhold information. That's one of the things we're not so happy with.

SALLY SARA: If there is that rider in terms of preserving Australia's security interests, you're not really going to know what kind of information is there and what's been left out, will you?

KATE GILMORE: That's absolutely correct. What we have to hold the Minister to, and indeed the government to, is a commitment to meet the same standards that the International Communities apply to itself in other comparable circumstances. Rwanda, Kosovo, Bosnia.

SALLY SARA: Your campaign and the meeting with Alexander Downer this afternoon, how does that fit into a wider campaign?

KATE GILMORE: Em, right around the region from Malaysia to Mongolia, from New Zealand to Taiwan, Amnesty International Members and supporters are rallying. They're rallying in the capital cities of the region's countries to demonstrate our support for justice for the people of East Timor, and to put pressure on our respective governments for them to support the establishment of an independent international tribunal to try these crimes against humanity.

SALLY SARA: So what have you really achieved, then, today? It doesn't sound as if the message from Alexander Downer is all that different to what he's been saying all along?

KATE GILMORE: Well there's ... it's important for non-government organisations like us to manifest to the government -which we did through presenting petitions of over tens ... signed by over ten thousand Australians - to manifest public expectation that the Australian Government maintain its resolve and keep its spine on the issue of justice for East Timor.

SALLY SARA: Is this a case of applying pressure well and truly in Indonesia's backyard?

KATE GILMORE: Absolutely. But it's also using East Timor as a springboard, if you wish, to establish a regional acceptance that impunity is unacceptable. That when you're a government official or a member of a high rank of an army, that's not sufficient grounds for you to get away.

From Amnesty International's Members' point of view, the region's population are now saying enough already.

COMPERE: Kate Gilmore, National Director of Amnesty International Australia, speaking to Sally Sara.

[Comment: Bravo Amnesty -- the Australia office, anyway. Head office in London has been much more laggardly in getting to grips with the scale of Timor atrocities.]

Ref.: SE06-1999/11/23eng

(distributed by East Timor Action Network, ETAN-News #43, 7 December 1999)

Summary:

The number of people in East Timorís interior, in towns and villages, plus those thought to be still in hiding in the hills and forests, added to those who fled or were forcibly taken to Indonesia, falls far short of 850,000 - the figure that, on the basis of the UNís ballot registration, was estimated to be East Timorís total population in August 1999. Between 80,000 and 300,000 Timorese have still not been located. This conclusion is gradually being reached by the international military force (INTERFET) and international humanitarian organisations working on the ground. A fresh census of the Timorese population is necessary and urgent.

Context:

After 24 years of Indonesian occupation, there are many unanswered questions concerning East Timorís population: most written records have either been destroyed or apparently lost. Prior to the 30 August ballot, the UN Mission conducted a voter registration process. Those in the territory who registered totalled 438,000. This number included Timorese over the age of 17 years who were eligible to vote and wished to do so. At the time, UNAMET believed that nearly all potential voters had registered. A few Indonesians, who had either married Timorese or had been born in East Timor, are also among the 438,000 registered voters, but most Indonesians had already left the territory by then. On the basis of the voter registration list, the UN estimated the total population of East Timor just before the ballot to be between 850,000 and 890,000 inhabitants. Subsequent doubts about these figures are more a result of the complexity of such a large numbers of people having "disappeared", than any well-founded criticism of the figures themselves.

The facts:

1. In early October, Jose Ramos Horta, Vice Chairman of the CNRT (National Council of Timorese Resistance) and 1996 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, raised the alarm about the possible "disappearance" of 100,000 Timorese.

2. According to the IPS news agency, [unidentified] UN staff had stated that "possibly 300,000 [Timorese] were still unaccounted for" (IPS, UN, 15.10.99).

3. On 1 November, the last of Indonesiaís soldiers left Dili. The UN intervention force believed that the people in hiding would then return to their towns and villages, said Col. Mark Kelly, INTERFETís deputy commander. Australian Broadcasting Corporation presented a quick calculation: out of a total population of 800,000 (!), if 250,000 had taken refuge in Indonesia, and 35,000 of those had already returned, INTERFET ought to have 600,000 under its control. "No, it does not have 600,000", said Col. Kelly. In spite of more than 5,000 hours of flying over the territory, the number of people detected in the mountains is small. There could still be some surprises. For example, Col. Kelly referred to when a Philippine military unit "literally almost bumped into over 20,000 people" who were living in the hills near Laclubar. He also suggested that perhaps "the initial estimate for the population was too high" (ABC, Australia, 1.11.99).

4. "There is a difference, we believe, of about 80,000 people. Are they are in the hills or just have not been located? We are not sure", replied INTERFET Commander General Peter Cosgrove, in answer to questions about the large number of Timorese still apparently missing. There were between 220,000 and 250,000 in West Timor, about 40,000 in other parts of Indonesia, 1,500 in Australia, and an estimated 100,000 in the 22 sub-districts still not covered by INTERFET. General Cosgrove thus reached a total of about 720,000, of the estimated 800,000 (!) at the time of the 30 August consultation (AFP, Dili, 3.11.99).

5. "Frankly, the numbers are a mess", said one high-ranking UN staff member who asked Reuters not to reveal his identity. "Many of the figures we are using are based on anecdotal information from different sources. It is very hard to cross-reference the differences", "the concern, obviously, is that there is a large sector that, at the end of the day, simply cannot be accounted for. Are they dead? Deported? So far, no one has a good understanding of the problem and it will be a long time before they do". Mario Carrascalao, who was Governor of East Timor from 1982 to 1992, believes that "In order to find out how many people have "disappeared", it is necessary to conduct a fresh census and to go to Indonesia to check, since many people could have dispersed among the archipelagoís thousands of islands" (Reuters, Dili, 1.11.99).

6. The Sydney Morning Herald pointed out that UN staff had estimated the total population as being between 850,000 and 890,000, and not 800,000 as General Cosgrove had stated. "Different UN officials calculate that the human cost of Indonesiaís bloody withdrawal could be close to 200,000" (Sydney Morning Herald, 5.11.99).

7. Mrs. Ogata, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, said that international humanitarian agencies had not yet uncovered evidence of killings on the scale they had initially expected. She stressed, however, that many people remained unaccounted for: "Itís a big island, whether they all went away by sea, I just donít know" (South China Morning, 12.11.99).

8. The Australian newspaper "The Age" wrote that neither the Australian nor the US intelligence services, which are both highly interested in monitoring Indonesia, have the answer to the question of those to whom humanitarian agencies refer as "the ghosts of Timor". "Many of them must have been killed. How many? Hundreds, thousands? Ė we do not know", said one intelligence agent quoted by the newspaper. "Where the hell are all these people? Where are they? All we can say is that we do not know" (The Age, Melbourne, 13.11.99).

Conclusions:

1. Many of the figures put forward are, in reality, estimates. The people responsible for handling these figures must do so with the utmost care and seriousness: the differences mean lives and deaths.

2. Whatever figures are used, the difference is in the region of tens of thousands, probably many tens of thousands. It would be illogical to dismiss the possibility of genocide before finding out what has really happened to all the "disappeared". There is increasing evidence that what happened in East Timor after the 30 August vote was a well-planned military operation that included careful attention to getting rid of the bodies.

3. On 3 November, INTERFET put the number of people whom it had managed to locate in East Timor at 334,015 residents. No information was given as to how this figure had been reached, but it meant that 500,000 people were not in the territory at that time or, if they were, they had not been found.

4. Efforts should focus on three directions:

a) To locate and identify displaced East Timorese in Indonesia and repatriate all those wishing to return. The precariousness of their situation makes this the number one priority. International organisations are going to find it increasingly hard to locate and contact displaced persons: as well as sporadic reports of refugees dispersing in Indonesia, there are statistics that suggest that this dispersion could reach high levels. The total number of displaced persons, confirmed by West Timorís authorities, dropped by 105,000 between 19.10.99 and 17.11.99 (the figure was 265,933 on 19.10.99, 219.000 on 28.10.99, and 161,000 on 17.11.99). This reduction is far in excess of the total number of people repatriated: 75,000 between 8.10.99 and 18.11.99 (including those repatriated from other Indonesian islands Ė Java, Bali, Flores Ė and even from Australia).

b) To identify all residents in East Timor and, therefore, to find those who could still be hiding in the mountains and forests. A fresh census of the population should be conducted (and perhaps temporary identification cards issued at the same time?) The disappearance and/or destruction of East Timorís public records means that UNAMETís voter registration probably now constitutes the most complete and systematic population record available. A comparison between the results of a new census and UNAMETís findings would indicate the humanitarian impact of Indonesiaís withdrawal.

c) To gather information about those who were killed and the "disappeared" and to try to identify them. In an attempt to obliterate the memory of the dead and make searching for the "disappeared" more difficult, destruction of public records was included as part of the genocide planned by the Indonesian military and the militias. Gathering information is also urgent and vital to the decisions that will be made regarding the international court for trying crimes against humanity.

Recommendations:

The UN Temporary Administration for East Timor, UNTAET, and the UN department for electoral operations, are the two bodies that are best placed to clarify the situation described above. Appeals should, therefore, be addressed to:

Sergio Vieira de Melo

UN Transitional Administration for East Timor

Att. UN Secretary-General

Fax: 1-212-963-4879

E-mail: ecu@un.org

Carina Perelli

Electoral Assistance Division United Nations

Room S-3235 A

New York, NY 10017 - USA

Fax: 1-212-963-2979

E-mail: perelli@un.org

Washington: Thousands of East Timorese refugees who fled militia violence are stranded in camps in West Timor where they continue to be intimidated by the army-backed groups, a US senator said yesterday.

"The West Timor situation is more problematic because of the existence of militias who are still receiving covert support from the Indonesian army," said Democrat Senator Jack Reed.

"The militias are targeting refugee camps and intimidating people not to go back" to East Timor, where a national referendum in August won the territory the right to independence, he said.

Reed, a Democrat from Rhode Island, recently returned from a two-day tour of West Timor and an inspection of efforts by the multinational force to establish order in East Timor.

"The people would be better termed hostages than refugees," said Pamela Sexton, an activist who has made several trips to the region in the past year, most recently last month.

She said Indonesian militia units were pervasive in the camps, harassing and killing any who expressed a desire to return to East Timor. "People are afraid to go back. People are trying to escape and being killed. Women are being taken from the camps and not returning," she said.

Ms Sexton based her reports on first-hand information as well as talks with Roman Catholic Church representatives who have a freer hand in the camps .

[Comment: If Ms. Sexton thinks, based on the evidence and testimony extant, that it is predominantly women who are "being taken from the camps and not returning," she needs to read some of the earlier Timor coverage on this site.]

High-ranking Indonesian military officers who ordered atrocities against civilians would escape prosecution because they were carrying out state policy, Dr Juwono Sudarsono, the country's defence minister, said yesterday.

Dr Sudarsono told journalists in Jakarta that only those soldiers who actually committed crimes and human rights abuses would stand trial.

"We can't go up into the high ranks, as they were just carrying out state policy," he said.

Dr Sudarsono, a political science professor who is Indonesia's first civilian defence minister, also made clear the military's intention to keep tight control of the archipelago, saying it would take five to 10 years before any democratically elected civilians could run the country alone.

He said the military would seize control if the new government of President Abdurrahman Wahid failed to rule properly.

Dr Sudarsono's warning came as one of the country's most powerful politicians, Mr Akbar Tandjung, denied there was a conspiracy to discredit Mr Wahid only weeks after taking office.

Mr Tandjung, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, said it was normal in a democracy to criticise the president, acknowledging criticisms of him from all political sides.

Dr Sudarsono said the first trial of soldiers charged with human rights abuses in Aceh would be heard in a joint civilian-military trial next week.

The decision ignores the recommendation of a government-sanctioned inquiry that former armed forces chiefs, including General Wiranto, the most powerful member of Mr Wahid's Cabinet, be put on trial for atrocities committed in Aceh.

Dr Sudarsono also warned that any action resulting from a United Nations investigation which has found evidence of Indonesian military responsibility for serious human rights violations in East Timor would have to be based on clear evidence "not story development, including news from foreign countries".

A five-member UN investigation team found evidence of atrocities, including the systematic destruction of property and the sexual assault of dozens of women [!] in East Timor.

But the team was forced to leave Indonesia without interviewing East Timorese living in appalling conditions in militia- controlled refuge camps in West Timor, because authorities in Jakarta were too late approving visas.

The defence minister said Indonesia demanded that a separate inquiry by Indonesia's Human Rights Commission take the lead in deciding any action against Indonesians.

The commission is believed to have made similar findings to those of the UN investigation.

One UN team member, Ms Sonia Picado, told journalists in Jakarta that "we have seen concrete violations of human rights with regard to the rights to life, the rights to liberty and the rights to property".

The team is expected to submit a report by December 31, recommending the setting up of an international tribunal to hear evidence of East Timor atrocities.

Australia says it is now clearer that the Indonesian military commanders were complicit in the terror campaign by East Timor militias.

A deputy secretary of Australia's Foreign Affairs Department, John Dauth, says elements of the chain of command of Indonesia's military (TNI) were directing the militia.

Mr Dauth told a Senate inquiry that his views on military involvement had evolved from evidence given earlier in the year.

"I believed then and I believe now that there were a lot of people acting outside of command and control arrangements in TNI," he said.

"I believe now, in a way in which I was not so clear then, that some elements of the TNI command and control at least were involved in that complicity."

[Comment: This will no doubt come as a shock to those returning from an extended sojourn on Mars.]

Leaked Indonesian military documents have revealed that soldiers who carried out killings and human rights abuses have been rewarded with promotions.

The documents show that military atrocities committed in the troubled province of Aceh, where government troops are fighting separatist rebels, have been carried out with the knowledge of Indonesia's military leaders.

In another blow to the Indonesian military's image, the country's commission on missing persons and victims of violence has released 400 pages of documents revealing that military violence in Aceh, on the northern tip of Sumatra, was well planned and part of an operational command.

It has evidence which conflicts with the statements of six former generals, who denied, during a parliamentary hearing, any involvement by Indonesia's top brass, claiming abuses were the work of individual undisciplined soldiers.

At least 2,000 people died in a 10-year military campaign in Aceh.

Separatists are now calling for a referendum like the one in East Timor, to decide whether the Acehense want independence.

[Comment: Interesting in the light of the article immediately preceding. Note that like East Timor, though on a smaller scale, Aceh has been the site of consistently gendercidal atrocities. For example: "About an hour's drive north of Lhokseumawe, in the foothills of the mountains, lies the hamlet of Cot Keng. Today it is more commonly known as Kampung Janda, or 'Village of Widows.' Seven women in the village lost their husbands during the army's counter-insurgency operations in the early 1990s." "Digging up Indonesia's past," The Economist, 12 September 1998. These "villages of widows" are apparently a widespread phenomenon. (It should be noted that the Aceh rebel movement (Aceh Merdeka) is by no means a cuddly bunch: see "Terrorizing the truth," New Internationalist, November 1999.)]

A United Nations investigator said yesterday that her team had found evidence of "systematic" murder in East Timor, but prospects for justice for the newly independent country remain uncertain after the Indonesian government declared its unwillingness to see senior officers prosecuted overseas.

"We will try not to deliver the generals to an international tribunal," the new Indonesian Foreign Minister was quoted as saying in the Jakarta Post yesterday. "We don't want generals unable to travel overseas and [liable to] be arrested like Pinochet."

The head of the UN Commission of Inquiry in East Timor, Sonia Picado, said that about 200 bodies had been uncovered Ė the victims of an explosion of violence by Indonesian troops and their militias after the country voted for indepen-dence from Indonesia in a referendum in August.

"The killings in East Timor were systematic," Ms Picado said in Jakarta after a nine-day investigation. "Every day you find bodies. So many people have died including women and children." [Comment: Anyone else?] But she declined to say whether she would recommend the setting up of an East Timorese war crimes tribunal such as those established for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia.

The Indonesian government has set up its own investigation, led by senior human rights lawyers, which announced this week that it would summon leading officers for questioning this month. The Committee for the Investigation of Human Rights Abuses in East Timor says it has drawn up a list of 60 generals involved in abuses, including the former armed forces commander, General Wiranto.

The new government of President Abdurrahman Wahid, which was democratically elected in October, has promised not to interfere with either of the investigations. But it still needs the support of the military, which has already been humiliated by the loss of Timor and by allegations of further human rights abuses and violence in the provinces of Aceh, Irian Jaya and the Spice Islands.

On Tuesday, the Defence Minister, Juwoni Sudarsons, warned that, unless democratic institutions in Indonesia are strengthened, "within months or years ... the military will come back in full force and take over from civilian control".

An Indonesian commission of investigation has blamed the country's armed forces for the violence and destruction in East Timor.

The commission, carried out under the auspices of the UN, places responsibility for the violence at senior levels of the military.

Indonesian human rights investigators have appointed the finger of blame for much of the violence and destruction in East Timor at senior military and police commanders.

The investigators say a pattern has emerged of the armed forces involvement in planning and in many cases standing by or participating in mass killings.

The commission says it has proof of the armed forces direct involvement in three known massacres in the towns of Suai, Liquica and Maliana.

However, it says responsibility is not limited to those officers directly involved.

It says superior officers based in Jakarta and the regional command post in Denpassar should also be held responsible for crimes committed.

Meanwhile, Indonesian President Abdurrahman Wahid has accepted a UN invitation to visit East Timor.

Foreign Minister Alwi Shihab says he will also come with the President.

Mr Shihab says an official invitation to visit East Timor, from UN secretary general Kofi Annan, had been conveyed to President Wahid by the head of the UN Transitional Administration in East Timor, Sergio Vieira de Mello, yesterday.

However, he could not give a date for the visit.

Indonesia's President Abdurrahman Wahid has given the go-ahead to prosecute Indonesia's top generals if there is evidence they were responsible for the murder and destruction that gripped East Timor three months ago.

The President said he would not interfere in the judicial process and would allow the courts to decide the fate of the generals, including his Senior Minister for Security and Political Affairs, General Wiranto, The Jakarta Post said.

"I will not be swayed by any temptation," he said.

"What is important is that we accept the decision of the court."

Military-backed militia gangs went on a violent rampage in East Timor following the announcement of the overwhelming vote for independence in a UN-sponsored plebiscite on August 30.

Hundreds of thousands of people were forced to flee their homes. The violence continued until international peacekeepers arrived on September 20.

State-appointed human rights investigators said military leaders may be held accountable for the violence since evidence showed they knew it was taking place and did nothing to prevent it.

"I believe [General] Wiranto could be charged with omission or failure to take action," Albert Nasibuan, head of the investigating team, said.

Last month, the group dug up the bodies of 26 people - including three Roman Catholic priests - who were massacred during September's violence.

They had been buried in mass graves after being trucked in from East Timor to Indonesian-controlled West Timor.

In all about 200 bodies have so far been recovered.

A senior legal adviser to the East Timorese leader Mr Xanana Gusmao believes that more than 20,000 Timorese who were forcibly evacuated after the independence ballot are still unaccounted for and says he holds grave fears for their safety.

Speaking on a brief visit to Sydney, Dr Manuel Tilman, co-ordinator of the legal task force for the East Timor Resistance Council (CNRT), says laborious efforts are being made to account for thousands of Timorese who have had no contact with their families since being removed from the territory by the Indonesian military in early September.

Timorese human rights workers are beginning the arduous work of going from village to village drawing up lists of those whose fate remains unknown.

"We don't know where these people are," Dr Tilman told the Herald, "maybe some are dead". They are not among up to 100,000 refugees in camps in West Timor, he explained, but some could still be scattered through Bali and other outer islands.

Since the forced evacuations, debate about how many Timorese died at the hands of the Indonesian military (the TNI) and pro-Indonesian militias has been intense. While initial media reports put the figure in the thousands, Australian officials now suggest the number is more likely to be in low hundreds.

Significantly, Dr Tilman, a Lisbon-educated lawyer, is in a privileged position to comment on the forced evacuations and killings by the TNI and the militias. Recently, he has been able to talk to several key militia figures who were once part of the TNI plans but are now collaborating with CNRT.

Their evidence, he believes, reveals an intense level of planning by the TNI and its top commanders for the destruction of Dili, the forced evacuations and some of the killings. This, he says, is backed up by documents held by human rights investigators which will be available to UN investigators for any case against the Indonesian military.

The evidence, he says, implicates General Wiranto, the former head of the TNI and now a minister in the Indonesian Cabinet, and four other senior officers.

"We have a witness who participated in meetings in March, in April and in May in Bali to prepare the violence."

Among those present, he claims, was General Wiranto, his regional commander in Bali, Major-General Adam Damiri, the chief of staff, Major-General Syafrie Syamsuddin, the local military commander in Dili, and Major-General Zacky Anwar Makarim, the TNI's liaison officer with the UN mission.

The officers under General Wiranto have all had past connections with Kopassus, the elite special forces of the Indonesian military which was responsible for strategy on East Timor from 1975.

A recent Indonesian Human Rights Commission briefing on the atrocities in East Timor revealed investigators wanted to interview the TNI officers, including General Wiranto, over meetings which plotted the destruction of East Timor and the killing of pro-independence leaders.

According to Dr Tilman there are also several militia witnesses who can give evidence about meetings in Dili with senior TNI officers, including Dili commander Colonel Tono Suratman, throughout July and August where killings and forced evacuations were discussed.

Evidence is also emerging, according to Dr Tilman, that the son-in-law of former president Soeharto - the disgraced Lieutenant-General Prabowo - was "supporting the militias with money".

EAST TIMOR: The Indonesian President, Mr Abdurrahman Wahid, said for the first time yesterday that senior Indonesian military officers accused of human rights abuses in East Timor should be tried.

While the move may be aimed at forestalling indictments by an international court, it could bring closer the downfall of Indonesia's leading military official, Gen Wiranto, and break the power of the military in Indonesia, observers in Jakarta said.

There has been a growing public clamour for the generals to be made to account for years of abu ses, especially in East Timor and the separatist provinces of Aceh and Irian Jaya.

In a BBC interview yesterday, Mr Wahid said: "If they issued the orders themselves, if they did the atrocities themselves then they have to stand trial."

Mr Wahid, who makes policy "on the run" each day, as one commentator put it, has by this statement overruled his Defence Minister, Mr Juwono Sudarsono, who said two weeks ago that officers in charge would not be tried because they were implementing government policy.

The Indonesian commission investigating atrocities in East Timor said last week it would summon several generals for questioning, including Gen Wir anto, who is Co-ordinating Minister for Political and Security Affairs.

This could open the door for Gen Wiranto to step down from the cabinet. If he does not, it could provoke a crisis between the army and Indonesia's first democratic government.

Mr Wahid said on Monday that his policy that cabinet ministers should be suspended if they were investigated by state prosecutors and fired if convicted remained unchanged.

He said: "My statement when I inaugurated them remains put, that ministers under legal probe must be deactivated, and must quit once the court convicts them."

Under the glare of international scrutiny, Indonesian officers now seem to be pulling the plug on the militias they created and sustained in East Timor and who are now an international embarrassment.

The militias were under the nominal control of figures like East Timorese landowner, Mr Joao da Silva Tavares, who on Sunday met East Timor independence leader, Mr Xanana Gus mao, at a military camp in Indo nesian West Timor.

In an extraordinary display of affection, Mr Tavares promised to disband the militias, who hold an estimated 169,800 East Timorese in camps in West Timor.

Similar promises of reconciliation by the militias in the past have proved not to be sincere, but Mr Tavares may be feeling that not only is he on the losing side but that his patrons are running for cover.

Sources in the region said the meeting was likely set up by Gen Wiranto to improve his image by being seen to move to end the human rights abuses against refugees in West Timor.

The most obvious charge prosecutors will put to Gen Wiranto is "guilt by omission", according to Indonesian newspaper reports of an inquiry commission set up by the National Commission on Human Rights chaired by Mr Marzuki Darusman, the state's attorney general.

As head of the armed forces, Gen Wiranto visited East Timor a number of times during the terror unleashed by Indonesianbacked militias and Indonesian soldiers before the arrival of a UN force in September.

He failed to stop the killings and arson after the August 31st UN-organised vote for independence, which left the former Portuguese colony 75 per cent destroyed.

Both the inquiry commission and a UN-sanctioned Commission for Inquiry in East Timor have blamed members of the Indonesian military and gangs of pro-Jakarta militiamen for the atrocities, and have accused the generals of letting the violence run unchecked.

Also facing questioning this weekend are former East Timor military chief, Brig Gen Tono Suratman; former East Timor police chief, Brig Gen Timbul Silaen; Maj Gen Zacky Anwar Makarim; Maj Gen Sjafrie Syamsuddin of the army's elite special force (Kopassus), and former Bali-based regional military chief, Maj Gen Adam Damiri.

Maj Gen Dimiri, head of the military area that included East Timor, allegedly held a meeting of militia leaders and promised weapons for 2,000 men and, at a later meeting of officers in Dili, planned operation "Global Clean Sweep" designed to destroy the East Timorese Resistance. Gen Wiranto has rejected all accusations of human rights violations in East Timor.

[Comment: Now it has a name.]

Interfet troops in East Timor's Oecussi Ambino enclave believe they have located up to 52 bodies buried in one area.

The grave site has been described as a killing field.

If the reports are confirmed it will be the largest mass grave yet found on East Timorese soil.

A report from an Interfet intelligence officer to Australian Defence Minister, John Moore says 52 bodies may be buried in a field near the Oecussi Ambino's enclave border with West Timor.

It is believed the killings were committed before Interfet's deployment when Indonesian soldiers, Indonesian police and militia recruits pursued pro-Independence supporters in the area.

Interfet believes 170 people have been killed in the enclave, and says militia are still active.

The United Nations is investigating 18 separate grave sites in the East Timor enclave of Oecussi which local Timorese claim could hold the remains of 52 people missing after post-referendum militia violence.

In a separate discovery, Australian Navy divers yesterday recovered the remains of about a dozen bodies dumped in a lake at Maubara, near Liquica, where pro-Indonesian militias were reported to have slaughtered 67 people in April.

The 18 grave sites are at Passabe in the south-east corner of Oecussi, a small chunk of land that is part of East Timor but straddles the north coast of Indonesian West Timor.

The United Nations' Dili-based director of human rights, Ms Sidney Jones, said: "We're clearly dealing with a large set of graves. It is a major [mass grave] site - that is clear.

"It's clear some of the graves may contain more than one body," she said, adding that the latest information indicated "head and bone parts from four bodies" had been recovered.

Local villagers had told investigators that the victims, all suspected independence supporters, had been taken by lorry from a small town called N'bate into Passabe, where they were executed.

Heavy seasonal rain in the area has exposed the human remains. The site lies in a remote area of Oecussi accessible only by helicopter, then by four-wheel drive.

Security near the site, several hundred metres from the West Timor border, is a big concern. Local Timorese have been guarding the area but members of the Australian elite Special Air Service Regiment and paratroops from Sydney-based 3RAR are also known to be in the area.

UN and East Timorese human rights officials said some of the worst allegations of atrocities committed by Indonesian soldiers and pro-Jakarta militia occurred in the enclave, the last East Timorese territory to be secured by Interfet peacekeepers.

Ms Jones said: "There were all sorts of allegations of major murders in the aftermath of the September violence but none verified. We've probably more reports from people coming out from Oecussi ... than from any other district."

The pro-independence coalition, the National Council for Timorese Resistance, claims 52 people are missing from around the area of the grave sites.

The human remains discovered in the lake west of Liquica are believed to be those of victims of an April 6 massacre carried out by Indonesian soldiers and pro-Jakarta militia.

Indonesian soldiers and members of the Besi Merah Putih (Red and White Iron) militia attacked the Liquica church where hundreds of unarmed people were sheltering.

The Dili-based Yayasan-Hak human rights group estimates 67 people were shot or hacked to death.

Two Australian forensic specialists arrived in Dili yesterday following a request for specialists by East Timor's UN Administrator.

The head of Sydney's Institute of Forensic Medicine, Professor John Hilton, and an associate, Professor Jeoffrey Wellburn, will establish a facility for international forensic experts, pathologists and anthropologists to further investigate grave sites.

The latest discoveries bring to about 200 the number of sets of human remains recovered by Interfet peacekeepers since they arrived in East Timor on September 20. Of those, 77 have been identified.

UN human rights investigators are examining more than 200 other potential sites across East Timor.

COMPERE: The discovery of two new mass graves in East Timor is expected to provide further evidence of the Indonesian military's key role in the slaughter of pro-independence civilians. Yesterday Defence Minister John Moore received a briefing on a killing field in the Ocussi, Ambino enclave, and as Geoff Thompson reports, divers have now discovered yet another mass grave.

GEOFF THOMPSON: Standing in front of a diorama of the enclave, Captain Plunkett reveals the grizzliest [sic] find yet on East Timorese soil. He points to a little cardboard sign labelled 'mass grave', a site which in the real world has revealed 14 bodies. But disturbed earth in what's been called the killing field suggests there could be as many as 52 victims of a mass killing - killings which witnesses say were done by Indonesian soldiers and police along with local militia.

CAPTAIN PLUNKETT: And they were basically targeting CNRT elements along that road. They rounded them up, put them on the back of a truck and they murdered them, according to witnesses, down here and along the road. [Note: This is almost certainly a gender-selective massacre of younger men.]

GEOFF THOMPSON: INTERFET commander Major General Peter Cosgrove called for caution until the grave site could be investigated thoroughly by UN civilian police. But he had this to say about witness suggestions that Indonesian forces were directly involved in the slayings.

PETER COSGROVE: That was the account. It was an account conveyed by inhabitants of the enclave. And accordingly, like the other facts of this awful tale, will need to be confirmed by a thorough investigation.

GEOFF THOMPSON: In a separate find yesterday about one dozen bodies were found in a lake in the town of Maubara just west of Liquica. Australian Navy divers were guided to the bodies by a local truck driver. He told them he drove a truck full of bodies to the lake after the Liquica massacre on April 6, when perhaps dozens of people were slaughtered in a church by the Besih Merah Putih militia.

That incident was the first major act of anti-independence violence to grab the world's attention this year. But it's only now, eight months later, that the bodies are being found.

COMPERE: Geoff Thompson reporting from Dili.

The Foreign Minister, Alexander Downer, has confirmed Australia will provide intelligence material about East Timor to the United Nations.

The UN has formally requested Australian intelligence on what the UN describes as a systematic campaign of terror in East Timor.

Mr Downer says the request was made a couple of weeks ago and the Government is in the process of putting together a formal response.

"We are happy to provide material in an appropriate form for the United Nations," he said.

"The United States and the United Kingdom provided material of an intelligence nature to investigations into human rights abuses in the Balkans, and we're using the way the US and the UK provided material as a model for the sort of approach that we'll be taking."

][Comment: This could be interesting; I earnestly hope the U.N. will attempt to interview the U.S. and Australian intelligence sources cited in the Sydney Morning Herald reports of 12-13 November (link to November coverage).]

East Timorese leaders say 20 people have starved to death in East Timor in the past week in one district alone, despite the presence of international aid agencies.

Portugal's Lusa newsagency quotes an official from the National Council of Timorese Resistance (CNRT), the territory's main political group, as saying the deaths had occurred in the Manatuto district.

The CNRT committee member said there is no food to give the starving, but did not elaborate. [Comment: Evidence of how lackadaisical has been the Interfet effort in key respects, and how frail or nonexistent is its presence across large swaths of East Timor.]

International donors have pledged to provide aid totalling $520 million to help East Timor recover from the devastation wrought by pro-Jakarta militias and prepare for full independence in two to three years.

War Crimes

Indonesia has ruled out allowing an international tribunal to try military leaders accused of war crimes in East Timor.

President Abdurrahman Wahid said he would allow an Indonesian court but not an international tribunal to conduct the hearings.

Former military chief General Wiranto and some senior army officers face allegations of complicity in atrocities committed in East Timor after it voted for independence.

Speaking to reporters in Jakarta, President Wahid said any outside body should respect whatever rulings the Indonesian court might render.

His statement came as a government-sanctioned commission of inquiry postponed hearing the evidence of General Wiranto, after his lawyers asked for more time to prepare.

United Nations

The special panel of the United Nations Human Rights Commission, which called for the establishment of a war crimes tribunal, says the UN Security Council should set up the tribunal whether Indonesia gives consent or not, if its authorities do not soon show they are actively investigating alleged war crimes by their troops.

The panel says it is too early to assess the full extent of human rights violations in East Timor, but they say it is clear that murder, torture and sexual violence all took place on a wide scale.

They say the evidence of the Indonesian Armed Forces' involvement in militia violence is already sufficient to incur the responsibility of the Government in Jakarta.

The stench of death went straight to the back of the throat, and instinctively the young woman put a cloth to her mouth. The InterFET soldier shook his head. It's worse, apparently, to try to smother thesmell.

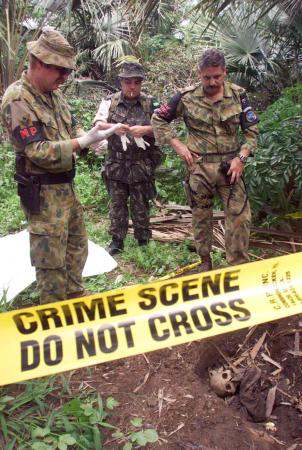

A razor-wire barricade and 20-odd InterFET troops held back scores of Timorese from the strip of grass leading to the beach. Just beyond, five empty graves lay open to a heavy sky. The exhumation was well under way. A high sheet of blue tarpaulin strung around some poles shielded three men in army camouflage and rubber gloves from the crowd. But, on the other side of the tarp, their makeshift mortuary was completely exposed. The pathologist held up a pair of rotting trousers, carefully examining the garment for holes. On the ground sheet sat a neat pile of bones with a skull. Beyond these sad remains, lay the next 11 graves, where diggers were still at work.

In the sweltering afternoon heat, a British police officer, one of the United Nations civilian investigators, was already briefing on the rudimentary examination. "They are able to tell us of stab wounds, puncture holes in clothing, skull trauma, bone trauma," said Detective-Sergeant Steve Minhinett, "so they can give us fairly accurately the cause of death."

Within minutes word came from behind the tarpaulin: the first three victims had died from multiple gunshot and stab wounds. "This will take our number through 100 in the Liquica region - that's 100 bodies," Minhinett said. "And we still have a considerable number after this."

An intense American woman in civilian clothes stepped forward. Sidney Jones, a long-time human rights activist, directs the human rights division for the UN's transitional authority in East Timor. She pointed to the empty graves. "The five bodies up here in front were buried as a result of killings on 6 April in the church compound of Pastor Rafael do Santos. The second group of bodies are 11 over here." She turned to the beach. "These were people killed in the attack on 17 April in Dili. "We want to find out the cause of death and whether people can identify the victims and match up physical evidence with witness testimony which we now have. "These bodies," Jones says, "make much of the evidence amassedso far so much more credible."

On this remote beach, an hour west of Dili, Jones is trying to corroborate allegations of horrific crimes, acts that may finally be classified as war crimes committed by Indonesian-backed militias, officers of the Indonesian army, the TNI, and Indonesian-led police.

Just how many Timorese died in last year's crisis and by whose order is a matter of intense debate at UN headquarters in New York, in Jakarta and Canberra. Before Christmas, Foreign Minister Alexander Downer tried to revise earlier wild estimates of tens of thousands slaughtered with a more sober figure in the hundreds. But already Canberra's revisionism is proving premature.

Here, on the north Timor coast, the methodical work of counting the dead continues. So does the investigation of who is responsible. "One thing is certain," says Jones, "the number of reports of people being killed and the number of reported grave sites is steadily increasing. As people are becoming more confident about coming forward, the number of cases is going up."

She insists it is far too early to give an accurate death toll, but says: "If I were to hazard a guess, I'd say somewhere between 1500 and 2000. That's based on very shaky data at this stage and ... it's going to be a very long, slow, laborious process before we have an accuratecount."

But Jones and others say the toll could go even higher. Tens of thousands of Timorese are still unaccounted for since September. While these figures are now thought [sic: claimed] to be the result of statistical errors, even InterFET's General Cosgrove says the numbers still trouble him.

Clearly, says Jones, the known body count, around 220, is no guide. She knows of almost 500 alleged killings still waiting to be investigated. The figures are confounding. But patterns are emerging. Certain regions of East Timor, such as Liquica, were hit hard. Pro-independence figures, members of the National Council of Timorese Resistance,or CNRT, were specifically targeted. Churches and priests who shielded independence supporters were attacked. In many cases, witnesses identify TNI soldiers and police as present at the killings. And, tellingly, bodies were often removed and attempts made to hide the death toll. These patterns will be vital in determining whethera war crimes tribunal will be established.

Inside the razor-wire barricade on the beach in Liquica stands a witness, Santiago de Santos Cencela. A few metres away, the body of his brother Raoul is being exhumed.

Santiago's eyes flit over to the makeshift mortuary as he talks about the day he saw his brother shot dead by militia in Dili at the house of a prominent independence figure, Manuel Carrascalao. With scores of other pro-independence supporters, Santiago sheltered at the Carrascalao home after fleeing militia attacks in the Liquica district. Hiding in the toilet, he watched about 100 "Thorn" militia besiege the house. He also saw TNI soldiers and police before he saw his brother shot.

The attack was reportedly ordered by Eurico Guterres, commander of the Dili militia and a vicious young criminal trained by the TNI. He is now sheltering in Indonesia. At least 12 unarmed civilians died inthe attack, including Santiago's brother and Carrascalao's adopted son. The corpses were removed on trucks while Santiago, with the living,was taken to the police station. There, he recalls, he was told to sign a statement saying only one person died in the brutal attack. He refused and was held for three days. Later he traced the bodies of many victims to the mortuary and tracked them back to Liquica.

As he watches the UN police on the beach lay out body bags for his brother and the others, Santiago appears both depressed and gratified. "For a long time, without the UN, we could not prove a massacre," he says. Now he wants justice. A local militia man has been arrested in Dili, but Santiago wants the Indonesian army held accountable." It is important for the Timorese to show to the world that Indonesia did something very wrong here."

Inside the razor wire, more Timorese are waiting. They hope to identify relatives from another massacre that took place 10 kilometres down the road at the church compound in Liquica town. UN police are investigating the deaths of about 60 refugees, many pro-independence supporters, who were slaughtered when they sought shelter in Pastor Rafael's church. The dead were taken away by truck, theirrelatives left to search for their remains. Since InterFET's arrival, scores of rotting corpses have been discovered on the shores of a nearbylake and now on this beach.

"Unfortunately," says one UN police officer, "it's impossible to say whether they have come from the church because there are so many other reported incidents of murder in the area."

The investigation into the Liquica church massacre is significant because many witnesses put Indonesian military and police at the scene. But Sidney Jones says proving a case against TNI officers will be difficult. "Certainly, there is lots of testimony of the TNI giving orders from behind the militias to advance on the people inside the pastor's compound. And there is some testimony suggesting there were planning meetings beforehand. But I'm not sure there are prosecutable cases against individual perpetrators."

ESTABLISHING this proof is critical to the case for a future warcrimes tribunal. From these junior officers, investigators need to trace the chain of command to General Wiranto and his senior command, who still claim ignorance of the crimes. At least one UN investigator thinks Western intelligence information will be essential to prove the case against senior Indonesian generals. And some classified material does exist.

Two days after the Liquica massacre in April, Australia's Defence Intelligence Organisation, in a secret report, blamed the Indonesian military, then still called ABRI, for failing to prevent the massacre. "It is known that ABRI had fired tear gas into the church and apparently did not intervene when the pro independence activists were attacked. "BRIMOB (Indonesian police) were allegedly standing behind the attackers at the church and firing into the air... ABRI is culpable whether it actively took part in the violence, or simply let it occur."

Whether the intelligence material is sufficiently direct is debatable. Far more contentious for the Federal Government is what its intelligence services knew about Indonesian military planning for the mass deportation, destruction and killings that took place after the UN-sponsored ballot on 30 August.

In the two weeks after the vote, massacres on the scale of Liquica occurred across Timor. More than 200,000 people were transported to Indonesian West Timor, many forcibly; thousands of homes and businesses were looted and burnt to the ground and major infrastructure destroyed. By any definition, these were war crimes.

Jones makes a telling point. As Dili burnt and militias put the UN mission under siege, Wiranto declared martial law throughout Timor on 7 September. Saying he had full confidence in his forces to stabilise the situation, he stalled the push for an international peace-keeping force to occupy the territory. A day later, two of the most chilling massacres were carried out, with apparent TNI complicity. One is only now coming to light, a mass killing in the far-western enclave of Oecussi, just a few hundred metres from the West Timor border.

In UNTAET's Dili headquarters, Superintendent Martin Davies peers over the top of his steel-rimmed glasses at the computer screen. The middle-aged British police officer with a greying beard taps away quietly, scutinising the Oecussi figures as the air conditioner blasts away the midday heat. Davies, the UN police chief, had just returned from the mass grave site in Oecussi. Although there were rumors about the site for weeks, it was mid-December before a witness could direct the UN to the area, which is only accessible by walking track.

It is impossible to know how many victims are buried there. Davies says figures are being bandied about of 52 to 54 bodies, but he cautions that much of the site is underground. "There are human bones and remains exposed on the surface at the moment that would give an indication there may be 10 or 12, but until the site's actually excavated we can't say."

The first allegations that "something massive has occurred" surfaced in October. Local CNRT people have given police a list of names, but it may be weeks before any bodies can be identified. But Davies is in no doubt there was mass murder at the site.

The same day as these killings, when Wiranto's troops were supposedly enforcing martial law, another massacre was under way in the mountain town of Maliana. An estimated 50 people were slaughtered in the police headquarters in a district then controlled by TNI's top ally in the militia, Joao Tavares. The witness statements, critically, put militia, police and TNI officers present at the killings, which took place inside the police station compound and in the grounds. The victims included pro-independence activists and refugees from surrounding towns. There are also allegations that some TNI officers had lists ofnames.

Jones is not sure about this evidence. "There were clearly a couple of people that were targets, more well-known pro-independence figures. But it also sounds as though it was a fairly mass killing.

"The problem is it took place in different rooms in the police station so you don't have anybody that can attest to seeing everybody killed. The testimonies we have are either from people who helped remove the bodies from the police station, or, in some cases, people who saw individuals murdered, but they were taken away from the rest of the crowd."

AGAIN, the disappearance of the victims is hindering investigators. "We haven't found any bodies, that's the problem," Davies says. "We've got witnesses there, and there's a figure of 53, but again..." He shrugs.

Some villagers have put the toll at 100. This pattern of cover-up points to organisation that needed the complicity of TNI at a seniorlevel.

Last May, when the UN ballot was agreed on, Indonesia resisted calls for international peacekeepers coming to Timor, insisting it would be solely responsible for security. Now there is mounting evidence that from the time former President Habibie first proposed the ballot in January, the top commanders of the TNI worked covertly with the militias to defeat independence through violence and intimidation.

In a rambling compound, back from the Dili waterfront, a team of East Timorese human rights investigators from the Yayasan Hak Foundation pore over documents, piecing together corroboration of the covert strategy by militias and the TNI. The foundation's headquarters was trashed during the Dili siege and much of their work lost. But under the guidance of a respected lawyer, Aniceto Guterres, the foundation is re-building its files.

Even with limited evidence, Guterres is adamant that Wiranto and his commanders are responsible. "General Wiranto is involved because there is a military doctrine that says soldiers in the field have to follow orders from above. If what happened here from January to September happened without his knowledge, it meant that all these soldiers deserted from his army; it means 20,000 deserted from the army.That's impossible, The fact is, General Wiranto knew."

That view has won some support from an independent Indonesian commission of inquiry into the atrocities now being finalised in Jakarta. The inquiry has targeted Wiranto's senior commanders - specifically the man who oversaw the Timor operation from Bali, Major-General Adam Damiri, and the TNI commander in Dili, Brigadier-General Tono Suratman, promoted from the rank of colonel after the crisis. The Indonesian inquiry has accused the generals of collusion in the atrocities. The generals are denying the claims and mounting a defence. But the inquiry's view is shared by Australia's Defence Intelligence Organisation, DIO. A 9 September paper on the TNI policy states: "TNI embarked on a finely judged and carefully orchestrated strategy to retain East Timor as part of Indonesia. All necessary force was to be employed with maximum deniability..."

In Dili, two former key insiders say they have first-hand knowledge of the TNI's secret operation. Sitting in the back yard of his brother's house, Tomas Gonsalves lights a cigarette and begins his story. Just a year ago he was a leading pro-Indonesian figure in Dili, a veteran who had fought with the Indonesian special forces in 1975. Now his weatherbeaten face tells a story of betrayal and disillusionment.

In late 1998, he says, he met Major-General Adam Damiri and Colonel Tono Suratman at the Dili military headquarters for his first high-level meeting about the militias. Joining them was Yayat Sudrajat, the head of the SGI, the feared intelligence task force attached to Kopassus. The Indonesians discussed the rumored referendum in East Timor, and secret plans to step up the training and arming of pro-Indonesia militia. Soon after, says Gonsalves, the SGI was distributing weapons to militias, and he was pressured to organise the operation in his own town of Emera.

Last March, the SGI boss arrived in Emera with three pickups loaded with weapons for Gonsalves to distribute. Two days later, he was called to a meeting with the pro-Indonesian governor of Timor, Abilio Soares. That meeting, he says, was chilling. After discussing the security needs of the pro-autonomy front, Gonsalves says the Governor told him that "in the near future there will be an operation throughout East Timor". As part of that operation, he says, they were told to, "kill all CNRT leaders, their families, even their grandchildren. If they sought shelter in the churches, even the bishop's compound, we were told to kill them all".

Despite being shaken by this meeting, Gonsalves agreed. But soon after a rift emerged in the pro-Indonesian leadership. Some were baulking at the planned level of violence. In early April, Gonsalves and other pro-autonomy leaders were summoned to Jakarta for a meeting with a senior general from Wiranto's headquarters.

Gonsalves says that Major-General Kiki Syahnakri impressed on them the need to go ahead with the militias. The TNI, said the general, "was getting weaker and the only way for the pro-autonomy forces to defend themselves is by organising the militia. If there are any sons of Timorese who wanted to fight for the red-and-white flag, they would support them with guns and money."

Corroboration of Gonsalves's story comes from Rui Lopes, another veteran of the 1975 war, who fought alongside Kopassus. Lopes says that in late 1998, Major-General Damiri flew him to Bali to persuade him to work for the pro autonomy cause. At first they wanted him to draw defectors from the independence ranks, but soon they stepped up arming and training militias. Like Gonsalves, Lopes is certain the weapons were distributed by Indonesian intelligence.

"The weapons came from (Colonel) Tono Suratman; he gave the green light. The Indonesians knew it was impossible to convince people to vote for autonomy even if there was a lot of money from the central government. By creating the militias, they wanted to make them scared to vote for us." Lopes says he had direct dealings with Major-General Zacky Anwar, the one-time head of Indonesian military intelligence who was the TNI military liaison to the UN mission during the ballot. Lopes says that in August Anwar advised him to set up a home base in West Timor in case a guerrilla war was needed to hold on to East Timor.

The testimony of these two insiders is significant, but on its own not enough, Sidney Jones says. The key question is whether these meetings and plans can be tied to individual deaths. "My own feeling is that you do what you can with low-ranking TNI soldiers, bring those cases forward," she says. "I don't think you can start with the top and work down. I don't think you're going to get evidence that will stand up in court until you have some of these cases with lower-ranking officers actually prosecuted."

One case is the massacre in the western coastal town of Suai. On 6 September, at least 100 unarmed Timorese civilians were slaughtered in the Suai church compound in a militia attack. Again, TNI and police were present. Among the dead was a Timorese priest, Father Hilario Modeira, and two colleagues. For both UN and Indonesian investigators much is at stake in the case.

In a burnt-out building in the mountains, a young boy sits in a white plastic chair, his feet just touching the floor. Until last September Toto lived in Saui with his cousin, Father Hilario. Toto says he wants to talk about the day "Papa Saint" died.

It was about two in the afternoon when he first heard the shooting. All day Father Hilario had tried to telephone police and army headquarters but nobody would answer. The only person he could reach was Bishop Belo in Dili. Belo told his priest to pray.

Toto says people began running everywhere as the shooting continued. He hid in Father Francisco's bedroom. He wanted to see Father Hilario on the veranda, but others hiding with him warned him to stay down. Then he heard a shot and Father Hilario fell. "He lay down on the veranda, saying please, please, help me and called out Father Cico's name. Then he died."

The boy and six others huddled in the bedroom until the compound was set on fire. Men began searching the house so they fanned the smoke to screen themselves. When it was quiet, the frightened survivors escaped. "I had to walk over the dead bodies. I think there were a lot of people, but I didn't count them."

In Dili police headquarters, Sergeant Sue King, a federal police officer from Sydney, is piecing together evidence on the massacre. In the months before the ballot, the church compound was a refuge for thousands of pro-independence supporters driven from their homes. Father Hilario's courage in sheltering the refugees brought the attention of US senators and the international media, but angered the local TNI commander and militia.

On 4 September, when the UN announced the overwhelming vote for independence, the priests knew they were sitting targets. Father Hilario urged thousands of refugees to leave the compound, but some were too frightened to go.

From witness statements, King now thinks about 400 unarmed people were left in the compound when the militia surrounded them. Her best estimate is that 100 people were slaughtered. Others say the figure is much higher. The wet season has hindered King's inquiries. "InterFET didn't investigate till much later and, with the rain, that crime scene was severely contaminated," she says.

But what evidence remained - blood stains and a pile of empty shells - spoke clearly of a massacre.

IT WAS the Indonesian human rights inquiry that announced the discovery of Father Hilario's body last November. Three graves were found 20 kilometres from Suai, on the Indonesian side of the border, that held the remains of the priests and 23 unidentified victims. All three priests were buried in a single grave.

The find was a breakthrough for the Indonesian inquiry, the first victims discovered on Indonesian soil. The discovery boosted the credibility of the inquiry, but East Timorese human rights activists and Sidney Jones remain sceptical. They doubt that the Jakarta inquiry - a fact-finding exercise with no power to prosecute - will lead to high-level convictions. Jones is sure the Wahid Government supported the inquiry to forestall an international tribunal.

The UN human rights panel has completed its investigation and is due to release its report on Monday. Jones, who has not seen the report, says the recommendations range from an international court with Timorese and Indonesian judges, to "border courts" set up under Indonesian law and Indonesian judges with some international participation. Despite the courage of the Indonesian inquiry, Jones doubts any Indonesian court will bring people to justice.

While most local observers say militia members should be tried in East Timor, the prosecution of the Indonesian command is the key issue. For the thousands of Timorese who lost homes, jobs, friends and family, the Indonesian commanders must stand trial.

In a ransacked office in his home town, Father Hilario's brother, Louis, fights back tears. His father and two brothers were killed under Indonesian occupation. His job is gone, his friends are dead, the local woman who worked for the UN raped and murdered. He steadies himself by lighting a cigarette. He is prepared to wait if necessary, but says a war crimes tribunal must come. "We want justice in the end. It will break the hearts of the Timorese if there is no justice."

The East Timorese selected for execution in the Oecussi enclave were first registered by Indonesian officials before being marched, hands bound, a short distance across the border where they were hacked to death by machete-wielding members of a militia death squad.

The East Timorese selected for execution in the Oecussi enclave were first registered by Indonesian officials before being marched, hands bound, a short distance across the border where they were hacked to death by machete-wielding members of a militia death squad.

Senior UN officials claim the executions were supervised by Indonesian army and police. At least one person was shot dead, possibly while trying to escape the frenzy of killing.

Miraculously, there were survivors of the Passabe massacre, the worst-known atrocity in September's post-referendum violence.

According to UN and East Timorese human rights officials, some 1,000 men, women and children were murdered in the violence that followed the August 30 ballot.

In a simple ceremony at the Dili morgue on Monday, a Catholic priest performed last rites on the 45 bodies exhumed over the weekend. The ceremony was organised to help calm and reassure East Timorese who would be working at the facility.

"It's always difficult when you are dealing with death, and we'll be dealing with death in large numbers," said Ms Sidney Jones, the head of the UN Human Rights in East Timor.

A stench swept over the small group of reporters, photographers and UN officials attending the commemoration as a security officer unlocked a commercial shipping container holding the human remains brought to Dili on Sunday.

"Show compassion for the East Timorese in this time of sorrow. We ask this, oh Christ our Lord," said Father Edmundo Barreta before he entered the darkened freezer container to sprinkle holy water on the bodies each individually wrapped in blue plastic sheeting.

Ms Jones said 36 bodies had been exhumed, plus nine sets of incomplete remains. They were recovered from a series of shallow graves dug along a sandy river bank marking the border with Indonesian West Timor.

At least two other bodies were unable to be recovered because they lay in quicksand. Another eight bodies lie buried on the Indonesian side of the river border near Passabe hamlet in the southern corner of Oecussi.

"They were clearly executed after they crossed the river into East Timor," Ms Jones said. "There was some form of registration process. They were taken into a government building and forced to register their names.

"It is the worst massacre of the post-referendum violence that we know of. We don't know exactly how many died at Liquica and Suai. This one, we know exactly. Most of the bodies are two or one to a grave."

Evidence gathered so far indicated the victims were mostly men taken on September 8 from villages near Passabe, identified by Indonesian authorities as pro-independence strongholds. According to accounts from independence supporters, between 52 and 56 men were marched across the nearby border into West Timor for registration. Their hands were then bound with palm twine and they were marched a short distance back into East Timor where they were executed, Ms Jones said.

On Monday the outgoing commander of Interfet military forces, Major-General Peter Cosgrove, said an arrest warrant had been issued against a pro-Jakarta militia leader, Laurantinio "Moko" Soares, implicated in the Oecussi violence.

A meeting yesterday exchanged further information on his activities and a warrant for his arrest on the West Timor side had been issued, he said. Interfet had been reassured by the new Indonesian commander of the appropriate military district that he was eager to produce "Moko" Soares for a joint investigation.

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

adamj_jones@hotmail.com