Gender-Selective Atrocities

in East Timor (3)

Coverage: November 1999

Compiled by Adam Jones, Ph.D.

Research Associate, Department of Political Science

University of British Columbia

C472 - 1866 Main Mall

Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6T 1Z1

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

For more on gender-selective atrocities against men,

including extensive Kosovo materials, see the Gender Page

of this website.

Jill McGivering,

"Fears Over East Timor's Missing"

BBC Online, 1 November 1999

Tens of thousands of people are still unaccounted for more than five weeks after the multinational force, Interfet, arrived in East Timor.

Following the final withdrawal of Indonesian troops on Sunday, local people still thought to be hiding in the mountains are expected to return to their homes. Others are known to be in camps in West Timor.

The departure of Indonesian troops is welcomed by locals

However, these approximate figures combined still fall far short of the region's original population.

Before the referendum on independence in late August, East Timor had a registered population of about 850,000 people.

When Interfet troops arrived on 20 September, after weeks of widespread violence, they found towns and villages burned to the ground and largely deserted.

The slow increase of Interfet's presence since then has made it possible for thousands of people to emerge from hiding places in the forest and mountains. Yet, visible evidence in the western parts of the territory suggest many houses remain empty.

Many East Timorese have returned to find their homes wrecked

Many people fled outside East Timor, some leaving by choice, others taken by force across the border into West Timor, or to other parts of the country by pro-Indonesian militia.

United Nations figures suggest about 240,000 people left, although accounts vary.

Indonesian authorities say 250,000 people went just to West Timor, but officials at the United Nations estimate that figure is closer to 150,000.

Most of these people are still in refugee camps across the border. Only about 35,000 have so far returned. Some of those who have come back say they were held in West Timor against their will by militia groups.

Refugees outside Dili are still being intimidated by militia groups

The Indonesian authorities signed a formal agreement with the United Nations two weeks ago guaranteeing free access to these refugees, but so far that has not been honoured.

Intimidation of the refugees by the militia, including beatings and killings, are still being reported.

Humanitarian workers say rumours are also being spread in the camps that Interfet soldiers are killing refugees who return.

But even taking into account the discrepancies in the figures available, many thousands of people have still failed to reappear on official data, raising questions about where a significant proportion of East Timor's original population has really gone.

"Hundreds of Thousands of East Timorese Still Missing"

Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 1 November 1999

MARK COLVIN: In East Timor the mystery of the disappeared is deepening as weeks go by. Where have all the people gone?

As the threat of militia violence appears to recede aid groups and the East Timorese are trying to track down all the people who used to live in the territory but it's a difficult task.

INTERFET and aid groups are largely relying on anecdotal evidence, but with no reliable figures for the population before the poll making an accurate assessment of the death toll in the recent violence is proving difficult.

Rafael Epstein reports from Dili.

RAFAEL EPSTEIN: As you fly over this violence racked country there are very few signs of life. The occasional small hamlet is occupied, most are empty.

Army Black Hawk chopper pilots who combined have flown more than five thousand hours over the territory say they see very few people in the hills. But it seems the East Timorese, adept at hiding in these mountains, can hide from anybody, even INTERFET.

As Chief of Staff, Colonel Mark Kelly, explains Filipino troops in the east quite literally stumbled on to 20,000 people living in the bush.

COLONEL KELLY: Up in the hills to the south of Manatuto again reports would suggest that there were very few people up in those hills there, yet the Filipino contingent went on a task where they went up into the high country around Laclubar, they've found in excess of 20,000 people that are existing up in that area.

Now with the weather, with flights over et cetera, there was not necessarily any visible sign of those people when we first arrived yet they have been existing, they weren't hungry, when the Filipinos contingent got up there, yet obviously they are now very pleased with the presence of the Filipino INTERFET troops so, you know, there's one example of a large group that were in the hills area, and that may set a pattern for other areas.

It's challenging country, how easy it is for people to be in those areas around those very steep features and it would take some time to find that they are there or reach them without patrols going out to sort of link up with them and encourage them to come back into the townships.

RAFAEL EPSTEIN: The United Nations registered just over 450,000 people to vote in the independence ballot. Most aid groups estimate the total pre-ballot population at more than 800,000 people. Privately the UNHCR says it's unlikely more than 250,000 people were forced to flee to West Timor.

With the return of around 35,000 already INTERFET should now have control of just under 600,000 people. They don't. For now Colonel Kelly says the initial population figure is too high.

COLONEL KELLY: No we haven't found 600,000 people in East Timor. But we need to sort of look at the detail of the numbers that we've got and can account for here now. That clearly is a focus of ours now, having stabilised East Timor, having troops around the regencies remaining vigilant and providing that security that's allowing and achieving pre-conditions, to have these people return....

RAFAEL EPSTEIN: Getting a grasp on the real numbers is difficult. INTERFET says it's relying on the UN's figures, but the UN says they're getting their information from INTERFET and in West Timor the UN is getting figures from the Indonesian Army.

But it's clear tens, if not hundreds, of thousand of people are unaccounted for.

COLONEL KELLY: Well we certainly hope nothing terrible has happened to them and the differences in the numbers that we're talking about here again we need to track that. We're here to actually facilitate the return of those IDPs from wherever they are.

RAFAEL EPSTEIN: In Dili, East Timor, this is Rafael Epstein for PM.

Michael Valpy,

"Rape and Murder in Sight of Our Lady"

The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 November 1999

(originally in The Globe and Mail, 1 November 1999)

THE heart of darkness in East Timor is the Catholic Church compound in this coastal market town - so still and empty, a silent statement on the evil that was done here.

What took place on the day and night of September 6 is not known in detail to Australian Army investigators. The number of victims and their identities are uncertain. What is known is that most were women and girls.

The evidence attests to that: the jumble of bras, underpants and sanitary napkins on the steps leading up to the church; the children's leg bones; a hank of a woman's hair; the scorched skeletal remains of two women behind the church; the thick bloodstain on a schoolroom door, covered by bougainvillea petals baking beneath the sun.

Certainly what happened was male savagery as old as history - rape, killing, burning, razing - in a church, a school, in the adjacent huge, grey, concrete shell of a cathedral called Ave Maria under construction to the glory of God. Savagery against the defenceless, as women and children usually are; vengeance on a people who voted for independence from their Indonesian military overlords and landowners.

The victims in the church compound, according to Australian investigators, were schoolgirls, nuns, other women and at least one priest. Maybe 100, maybe 200 were killed. Some had been raped. Some had been decapitated, their bodies burned on a cement terrace in front of the church, their remains carted away by trucks.

The military investigators arrived at the compound on October 14, the day after Interfet forces came ashore on Suai's beach. The investigators found dogs playing with human bones.

Last Friday morning, a contingent from Canada's Royal 22nd Regiment - the Van Doos - joined the force at Suai. The following day, I walked around the church compound with Captain Ben Farinazzo of Australian Army intelligence, military policeman Lieutenant Troy Mayne, and a security escort, Sergeant Martin Ryan.

Captain Farinazzo, the interpreter at Australian brigade headquarters in Suai, became quiet and noticeably uncomfortable as we moved through the ruined buildings, leaving us a couple of times to stand thoughtfully by himself.

"The first time I came, my reaction to the story was pretty matter of fact," he said later. "Now, more and more when I come back, I get an emotional reaction."

The story of what happened in the compound is incomplete. The investigators have not found many witnesses. Most of the Suai region's population, between 10,000 and 14,000, is still missing. Women and children were carted away on trucks to Indonesia's neighbouring West Timor province, about 30 kilometres away, where they are still being held. The whereabouts of many of the men is not known.

This is what the Australians have pieced together. The evil began a few days after the August 30 independence referendum. Indonesians owned many of the coffee and agricultural plantations around Suai. The town was a stronghold of the pro-Indonesia militias, most of whom were from West Timor. Some of the militiamen, mainly local officials, had been recruited in town.

After the vote result became known, soldiers and militia gangs began rounding up people from the outlying villages, bringing them to Suai's district military headquarters.

Father Hilario Madeira, pastor of the church of Nossa Senhora de Fatima (Our Lady of Fatima), went to the headquarters and got permission for the people to move to the church compound.

Several thousand, mostly women, set up a shanty town there. Many of the men, prime targets of the militias, had already fled to the hills, Lieutenant Mayne said. The women were thought to be safe once they got inside the compound. Safe from murder, he emphasised. No-one was safe from rape.

At dawn on September 6, militia and some soldiers took up positions along the front wall of the compound, across the street from the market in the centre of town. They began firing at the crowd inside. There was panic. Most people ran helter-skelter from the compound. Some didn't. Some went into the partially built cathedral to hide. About 200 ran to the church. It is believed that children were in the classrooms of the adjacent school.

When night fell, killing teams were sent in. They first hunted victims in the cathedral.

I climbed to the unfinished third- and fourth-floor galleries with Lieutenant Mayne. He pointed out the bloodstains where three people were shot, their bodies dragged to the edges of the construction site and thrown to the ground.

The attackers then moved to the one-storey row of pale-yellow schoolrooms between the cathedral and the church, smashing furniture, strewing schoolbooks over the floor, torching the buildings with petrol. They killed someone at a classroom door.

Investigators surmise that several schoolgirls or women, or both, were herded together near the church, ordered to strip, dropping their underwear in a pile on the ground, and were then raped. At the church, the attackers burst through the front and side doors and began firing at people inside. The absence of bulletholes in the walls indicates most of the attackers found their mark, Lieutenant Mayne said.

One of the witnesses was Father Hilario's 13-year-old nephew. The boy described how militiamen with machetes moved into the church, hacking at people, decapitating some. Father Hilario was shot as he pleaded for lives to be spared. A little heap of flowers along one wall marks where he died.

Cans of petrol were thrown on the church roof and ignited while people were still inside. The resulting blaze must have been a terrible inferno. The roof collapsed. Two four-wheel-drive vehicles and a tractor parked behind the church were reduced to burnt-out hulks. The skeletal remains of the two nuns - most of their bones burned to powder - were found in their charred quarters behind the church. A leg lay beneath an iron bedframe. Father Hilario's nephew, Atio, somehow escaped, his face and right arm burned.

The bodies of the dead were pulled from the church, piled outside, doused with petrol and set alight. What was left of them was then loaded onto three army vehicles and driven away. The site of their cremation - an area five metres square - has been ringed by stones and strewn with flowers. A skull fragment lies there, and the hank of woman's hair and some bones and a little stack of heat-blistered belt-buckles.

Much of the story remains to be told. What happened to the teaching sisters who lived in a convent, burned and wrecked, on the other side of the church compound? Where are the schoolchildren? Where do the bones keep coming from? How many were killed? Who gave the orders to slaughter them?

Letter to the Editor: Re Valpy

[The following letter was sent to The Globe and Mail

after the publication of Michael Valpy's piece,

just cited, on 1 November.]

To the Editor:

Reading Michael Valpy’s article “Male savagery as old as history” (The Globe and Mail, November 1) made me queasy, but not for the reasons he apparently intended. It is disgraceful that Mr. Valpy should concentrate his attention overwhelmingly on “worthy” victims of the Timorese conflict – women, children, nuns – and say nary a word about the brutal gender-selective atrocities visited upon East Timor’s defenceless male population in recent weeks. The Globe and Mail has been almost alone in reporting the phenomenon of mass gender-selective disappearances prominently (see the front-page article, “The chilling disappearance of East Timor’s young men,” September 16). Even Mr. Valpy acknowledges in a vague way that while Timorese women and children have been predominantly carted off to refugee camps in West Timor (the Suai massacre notwithstanding), “the whereabouts of many of the men is not known.” Meanwhile, fragmentary media and human-rights coverage strongly suggests that mass execution, dismemberment in machete attacks, and torture to death has been the fate of thousands if not tens of thousands of civilian Timorese men in recent weeks (see the coverage I have compiled [on this website]). Militia have reportedly pledged to create a “nation of widows” in East Timor.

What justification can Mr. Valpy claim for virtually eliminating the male victims of this genocidal assault from his analysis, and focusing instead on the evil male perpetrators and the violence they do to women and children? Are Timorese men simply the victims of “male-on-male” violence, and thus deserving of no empathy or attention? By the same token, I suppose Mr. Valpy could dismiss the Tutsi genocide of 1994 as “black-on-black” violence or “tribal warfare” (another phenomenon “as old as history”?), or female genital mutilation as merely “women cutting women.” But I’m sure such formulations would seem very redneck to him, as they do to me.

If Mr. Valpy wishes to explain decades of Indonesian violence in East Timor, continuing at this moment in the militia-run camps of West Timor and the growing Timorese diaspora around the archipelago, he would do better to consider such factors as Javanese imperialism and neo-colonialism, economic collapse, and corrupt political manipulations, rather than some abstract “male savagery.” Implicitly blaming the majority category of victims for their own suffering, by ignoring them, says more about Mr. Valpy’s bias and insensitivity than about the situation in East and West Timor. This situation remains deeply disturbing. As I write, there are perhaps a quarter of a million Timorese still missing, not counting those in the camps for refugees/abductees. We, and Mr. Valpy on the scene, should be devoting every effort to ascertaining their whereabouts and ensuring their physical safety, rather than effacing them from the equation.

Sincerely,

Adam Jones, Ph.D.

Executive Director, Gendercide Watch

Vancouver, B.C.

David Lague,

"A Creeping Fear: Where Are the People?"

The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 November 1999

The international force in East Timor has been unable to find the hundreds of thousands of refugees aid agencies claim are hiding in the hills, despite weeks of widespread patrols in remote areas.

Australian troops with the international force Interfet are now patrolling remote hills between the capital, Dili, and the border with West Timor but have failed to locate big concentrations of East Timorese thought to have been displaced in a wave of militia violence in September.

The Interfet spokesman, Colonel Mark Kelly, said yesterday that it was possible estimates of people hiding in the hills were incorrect.

"We certainly hope that nothing terrible has happened to them," he said.

Aid agencies estimated there were more than 800,000 people in East Timor before pro-Jakarta militia went on the rampage after the overwhelming vote for independence at the August 30 ballot organised by the United Nations.

They believe about 260,000 were shipped to West Timor or fled across the border before peacekeepers arrived on September 20 and that several hundred thousand abandoned their homes to hide in remote hills.

However, as refugees trickle back from West Timor, there has been no sign of huge numbers returning to their homes from inside East Timor. Thousands of small hamlets over wide areas of the former Portuguese colony remain uninhabited.

Colonel Kelly said Interfet patrols had found some people in the hills and it was possible rugged terrain made it difficult to spot major groups, even from the air.

Philippine soldiers searching the hills south of Manatuto had recently located 20,000 people in that area, he said.

"That may set a pattern for other areas," he said. [...]

"Mass Graves Still Being Found in East Timor"

ABC (Australia) News Online, 2 November 1999

Mass graves are still being found in East Timor, with the local human rights commission saying it has found 136 bodies in Dili alone.

The Human Rights Commission of East Timor is run by volunteer students, determined that militia crimes will not be forgotten.

Operating out of a deserted house in the centre of the city, they have no money and no resources, but continue to assist Interfet military police in locating bodies.

Yesterday, they took two MPs to a suburb in Dili to a grave containing the bodies of six men.

They say the men were killed just days before Interfet arrived.

The students have investigated just over 200 graves but have been unable to complete the investigation of every site.

Last week Interfet said the total number of bodies found by its investigators was around 100.

"U.N. Asks Megawati to Open Militia-Run Refugee Camps"

The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 November 1999

Geneva: The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees says it has asked Indonesia's new Vice-President, Ms Megawati Sukarnoputri, for help in gaining full access to refugee camps in West Timor.

The agency said it had repatriated East Timorese mainly from refugee centres in church compounds and Indonesian government-controlled areas in Kupang, capital of West Timor.

But it had been given only limited access to refugee camps controlled by militia groups which had fought against independence for East Timor, it said.

An Indonesian rights body has also criticised militia control of the camps.

The National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) said it had found evidence of organised human rights abuses by pro-Jakarta militia in West Timor, and urged Jakarta to protect the remaining 230,000 refugees East Timorese there.

The UNHCR said that after the centres under Jakarta's control were cleared last week, "the number of returnees substantially dropped". About 300 refugees were transported from a transit centre in Kupang on Monday, compared with 4,500 people several days earlier.

A total of 16,938 refugees had returned to East Timor under UNHCR auspices as of Monday, 10,867 by air and 5,955 by boat. An estimated 4,000 other people had returned unaccompanied on foot, and an additional 116 crossed the border on Friday in trucks and on foot.

The UN agency's regional representative, Rene van Rooyen, delivered the appeal to Ms Megawati on Friday during a meeting, in which she had expressed her support for UNHCR programs.

The UNHCR has welcomed the completion of Indonesia's troop withdrawals from East Timor, saying it hopes this paves the way for faster repatriations. The last Indonesian soldiers left the East Timorese capital, Dili, on Sunday.

The Indonesian Government has said there were 219,000 East Timorese refugees in camps in West Timor.

Komnas HAM said that about 21 militia groups in West Timor had committed "systematic and organised human rights violations".

"Forced disappearances [of ?], arbitrary detention [of ?] and violence against women have occurred there. The freedom with which they can operate has created a deep and widespread fear among the refugees. Neglecting the militia operation shows a significant relationship between [Indonesia's] security forces and the militia."

That relationship had hampered the work of a commission inquiry team and that of international human rights groups, the inquiry team head, Mr Albert Hasibuan, said.

Mr Hasibuan said the vicious Aitarak (Thorn) and Red and White Iron groups had been intimidating refugees in several camps in Kupang.

The government had therefore needed to increase "security guarantees" for the refugees to return to East Timor and to put "an immediate stop to" and "disband the militia groups", Mr Hasibuan said.

"Testimonies from witnesses revealed that militia have arrested, threatened and terrorised the refugees. One militiaman supervises 10 to 15 people. The militia often threatened the refugees if they said they wanted to repatriate.

"Other witnesses have also reported that militiamen have kidnapped East Timorese girls from the camps, and the lack of security has made these girls susceptible to sexual violence."

The refugees have said they feared the young men were being drafted into guerilla-style militia armies to fight UN troops in East Timor, under threat that their families in the camps would be killed.

"Interfet Claims 80,000 Timorese Still Missing"

ABC (Australia) News Online, 3 November 1999

The head of the multinational force in East Timor, Major General Peter Cosgrove, says at least 80,000 displaced East Timorese have yet to be accounted for.

General Cosgrove says United Nations human rights investigators will begin their work by the end of the week.

This is the first time Interfet has collated figures with the UN and aid agencies to calculate how many people are now in East Timor.

But it is impossible to conduct an accurate census and the exact numbers still are not clear.

Interfet says the initial population was between 800,000 and 850,000.

They now believe 440,000 are in the territory with another 280,000 in other parts of Indonesia and Australia. [Comment: So go get them.]

With at least 80,000 people unaccounted for General Cosgrove concedes some of the missing have been killed.

However, he says Interfet have confirmed only 108 violent deaths.

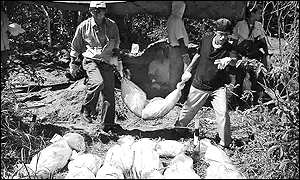

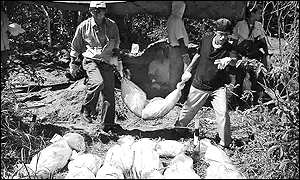

Original caption: "International Force for East Timor (INTERFET) forensic experts examine bones of human remains exhumed from a shallow grave in Dili, East Timor, Wednesday, Nov. 3, 1999. About 100 bodies have been recovered so far around East Timor and none of them have been identifed yet. (AP Photo/Erik De Castro, Pool)."

Original caption: "International Force for East Timor (INTERFET) forensic experts examine bones of human remains exhumed from a shallow grave in Dili, East Timor, Wednesday, Nov. 3, 1999. About 100 bodies have been recovered so far around East Timor and none of them have been identifed yet. (AP Photo/Erik De Castro, Pool)."

Kurt Schork,

"Fate of Timor Missing May Never Be Known - Cosgrove"

Reuters dispatch, 3 November 1999

[...] INTERFET reckons 454,000 people are in East Timor; about 225,000 in Indonesian-controlled West Timor; 40,000 elsewhere in the Indonesian archipelago; and 1,500 in Australia as refugees.

That would leave roughly 80,000 of what Cosgrove believes were East Timor's 800,000 people unaccounted for.

He referred to the 80,000 not as "missing" but as a "discrepancy" and said it might be explained by inaccuracies in other assumptions built in to the numbers.

Alternatively, he said, "there could be more in West Timor than we've actually found. [Comments: You haven't "found" anyone in West Timor.] There could be some in the hills (of East Timor). There could be some in the other, wider areas of the archipelago.

"Or it could be a combination of the three. That could total roughly the 80,000. There is always speculation about a fourth fate for some of these people."

So far there is little evidence to substantiate speculation about a "fourth fate." INTERFET has identified 108 bodies that it says appear to have met a violent death.

Cosgrove said a great margin for error in INTERFET population estimates made it too soon to rule any possibility in or out.

Speaking of the estimates, Cosgrove said: "It's probably one up from a guess, but certainly not in any way to be deemed as the most reliable figures ... every figure is approximate."

The U.N. Transitional Administration (UNTAET), using the 1998 census and 1999 voter registration figures, estimates East Timor's population was 850,000.

That would add another 50,000 to the total unaccounted for. U.N. officials have also said that they are deeply skeptical about the numbers of people being held in camps in West Timor.

The original figure of 260,000, of whom about 35,000 have recently returned to East Timor, was based on Indonesian statements, not on an accurate camp census [n.b. and the U.N. believes it to be much lower].

"Interfet Head Says 80,000 East Timorese Unaccounted For"

Agence France-Presse dispatch, 3 November 1999

[...] On Wednesday journalists returning from the the town of Suai, 25 kilometers (16 miles) from the border with Indonesian-controlled West Timor, said they had been presented with skulls by three townspeople the day before.

"There were three or four people with T-shirts wrapped up in their arms. One squatted on the ground and rolled out the T-shirt and it had a skull in it," said Australian photographer Leon Mead.

"Then after that, another squats down and rolls out another head and a smashed Jesus and Virgin Mary, and a third one (rolls out a bundle) with (a skull with) big tufts of hair, and that had some leather bracelets, necklaces and crucifixes."

He said one of the skulls had a deep machete wound in it.

Suai churchyard was reportedly the scene of a massacre of more than 200 people including the parish priest by pro-Jakarta militia who wrought havoc in East Timor after the independence vote.

Cosgrove said there were still between 220,000 and 250,000 refugees in West Timor, who were pushed or fled across the border to escape militia violence.

He said the first visit by UN rapporteurs examing human rights violations and summary executions would begin on November 6.

Of the total known numbers of East Timorese -- he said about 40,000 were around the Indonesian archipelago and 1,500 were in Australia.

Another 334,015 had been accounted for inside East Timor, of which 80,000 were in Dili, and an estimated 100,000 were inside the territory in 22 subdistricts not yet covered by Interfet. [Comment: General Cosgrove's forces still have not "covered" 22 subdistricts, and yet he claims to have an idea where the population of East Timor is!]

"Interfet Releases Official Population Figures for East Timor"

Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 3 November 1999

COMPERE: It's the burning issue for those who remain in East Timor. Where are the missing brothers, sisters, parents and friends? Interfet has now produced the first official population figures for the newly independent territory and the fate of more than 80,000 people is unknown.

While the international force admits its figures are approximate, it's clear the dislocation of the East Timorese was brutally successful. While we still don't know the fate of tens of thousands of people, Major General Peter Cosgrove has repeated his call for the UN to speed up its investigation into the murders we do know about.

Raphael Epstein reports from Dili.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: It was the question is Dili and other cities were torched by the militia, and it's still the question uppermost in the minds of the East Timorese. Who was killed, and how widespread was the torrent of militia slaughter that brought hundreds of thousands of people to flee to the hills and into West Timor.

After comparing figures with Aid Agencies, Interfet Commander Major General Peter Cosgrove says more than 80,000 people are missing.

PETER COSGROVE: Every figure we gave you was approximate. I'd like to be able to say no, that figure's dead accurate and all the rest can be approximate, but they're all approximate. It's probably one up from a guess, but certainly not in any way to be deemed as the most reliable figures that you all want. There are large gaps where information is not yet available.

The issue of hundreds of hundreds of thousands unlocated - it's probably not quite at that order of magnitude. There is a discrepancy, we feel, of about 80,000.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: General, what are the various possibilities? Can you run through where those 80,000 people could be apart from the accounts presently at stake?

PETER COSGROVE: Sure. There could be more in West Timor than we've actually found. [Comment: I didn't realize Interfet had actually "found" anyone in West Timor.] There could be some in the hills and there could be some in the other wider areas of the Archipelago, and that could be a combination of all three and that could total roughly the 80,000. And the answer is, of course, inside there there is always speculation about a fourth fate.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: It's clear somebody has successfully carried out the forced deportation of a substantial part of East Timor's population. Interfet says 40,000 people have been spread around the Indonesian Archipelago. Two hundred and fifty thousand are in West Timor, and it's best guess on East Timor's current population is 440,000. That means Interfet cannot find a large number of people - between 80,000 and 130,000.

While General Cosgrove says it's possible a large portion of those people were killed, he doubts it.

PETER COSGROVE: Look, I can't rule out anything, I can just say that the evidence is all that we can go on and our evidence at the moment shows us that the numbers of dead that we know to exist through some kind of violent end is in the hundreds, not the thousands.

I just don't know. I think what we've got to do is continue to gather evidence, and if people say there's been this event and they can describe it and there's corroborating evidence, this is a matter for properly constituted investigative agencies and ultimately a matter for us, because it does impinge on the peace and stability of the handover.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: The evidence of mass killings that does exist is slowly being lost. Already Interfet police have had to seal one mass grave because of the physical and medical risk. It's clear the UN and Interfet police already here don't have the expertise or the resources they need.

Yesterday the US Ambassador to Jakarta said he couldn't understand why the UN was dragging its feet, still not having dispatched special forensic investigators. They're now due on the weekend but General Cosgrove has again said their arrival is long overdue. [Comment: Fiddling, burning ...]

PETER COSGROVE: Yes in terms of the fact that we would want them here to be able to satisfy, I guess, the world's urge for information. Obviously you ask us questions we're unable to answer, and I think they're valid questions.

I mean ... I suppose in very pragmatic terms they will not prevent the tragedy, they will simply move to resolution. So in that sense, I suppose, there has not been the urgency to discover - simply a world wide urge to resolve.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: In Dili, East Timor, this is Raphael Epstein for PM.

David Lague,

"Timor Genocide: The Grim Counting Begins"

The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 November 1999

There are 80,000 East Timorese still missing more than seven weeks after Interfet, the Australian-led international force, halted a violent rampage in the former Portuguese territory, according to estimates compiled by the peacekeeping troops.

Some United Nations officials believe the number may be closer to 200,000 but an accurate picture of the human cost of Indonesia's bloody withdrawal from East Timor may take years unless Indonesia allows the speedy return of refugees from West Timor and other parts of Indonesia.

The commander of Interfet, Major-General Peter Cosgrove, said yesterday he was unable to rule out the possibility that many of the missing people had met a "tragic fate".

"The number of bodies actually located by Interfet is just over 100," he said. "I can'trule anything out. The evidence is all we can go on. I just don't know. We may never know."

The UN estimates that more than 75 per cent of East Timor's population was displaced, many forcibly taken to West Timor,in the wave of destruction and violence after an overwhelming majority voted for independence from Indonesia at aballot on August 30.

Pro-Jakarta militias and their supporters in the Indonesian military were forced to halt this rampage when Interfet was deployed on September 20 but vast areas of East Timor remain empty of people.

General Cosgrove said yesterday that of a total population of 800,000 before the crisis, Interfet believed about 720,000 could be accounted for, including up to 250,000 still in West Timor and 40,000 elsewhere in Indonesia.

However, UN officials believe the total population was between 850,000 and 890,000 before the ballot, according to 1998 projections drawn from Indonesian census figures.

Confidence in these projections increased when more than 430,000 East Timorese registered to vote in the ballot.

UN officials believed that almost all eligible voters registered, and this was about the proportion of the population that could be expected to be in that age group, based on the total population estimate.

Refugees continue to trickle back into East Timor from West Timor but General Cosgrove said yesterday he was frustrated that Interfet had been unable to meet senior Indonesian officers to co-ordinate security for bringing East Timorese home.

Relations with senior Indonesian military in West Timor over border issues had become "chronic", he said. [...]

"East Timor Cases Overwhelm Investigators"

Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 4 November 1999

When the United Nations announced an inquiry into the militia slaughter in East Timor, the world breathed a sigh of relief, confident that someone would be investigating the crimes committed against the East Timorese. But more than seven weeks after Interfet's arrival in Dili, the UN special investigators are yet to arrive. And a small number of military and civilian police who are there are overwhelmed by the sheer number of cases they're asked to investigate.

COMPERE: When the United Nations announced an inquiry into the militia slaughter in East Timor, the world breathed a sigh of relief, confident that someone would be investigating the crimes committed against the East Timorese. But more than seven weeks after Interfet's arrival in Dili, the UN special investigators are yet to arrive. And a small number of military and civilian police who are there are overwhelmed by the sheer number of cases they're asked to investigate.

There are still no forensic scientists, no morgue and no real capability to investigate graves that are quickly deteriorating as the wet season approaches.

Raphael Epstein reports on the few people on the ground who are doing what they can.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: Local Red Cross workers scramble up a hill with a black body bag. Its contents - two skeletons. Australian military police on the scene believe the two people were slaughtered with a machete and dumped over a small bridge into a creek. On this hillside just a half hour's drive West of Dili, a military Chaplain pays his last respects.

CHAPLAIN: We must encourage constancy and hope through him who died and was buried and rose again for us, Jesus our Lord. Amen.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: The military police unit here in East Timor has just 12 offices. Every day their small unit receives five to ten new reports of bodies or mass graves. Many of these policemen have never even conducted murder investigations, but the man in charge has.

Officer John Harvey from the British Army worked in Bosnia on war crimes and he says there are two problems in East Timore: there's still no UN special investigators, and there's no scientific examination of the bodies they recover.

JOHN HARVEY: There is no morgue facility. There is no forensic pathology ... you know. Once you have a body, what do you do with it if you haven't got a morgue to preserve or to carry out a post mortem? How do you deal with that? Unfortunately, because of the way the facilities are at the moment, all we can do is recover that body, get it medically examined at the time, photograph it, video it.

If there are particular things which we can see or we can obtain from initial scenes of crime aspect, we can recover those items, bag them, type them, log them, keep them until such time as we can get forensic pathology, post mortem facilities. The bodies are recovered - we have a specific burial site here in Dili where the bodies are put until such time as we're going to have these facilities.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: Is there a resource difference between here and Bosnia in terms of numbers of police officers and numbers of cases?

JOHN HARVEY: Yes, I would have said there was. For whatever reason the setup here, basically forensic pathology isn't here whereas it is in Bosnia, it was in Kosovo, it's not here.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: How important is local information from people on the ground?

JOHN HARVEY: Oh, desperately important. I mean without witnesses or tangible evidence to go with that, a lot of these cases will remain unsolved. So, you know, the more people that come forward and the more people that tell us what they've witnessed, what they saw, it helps us no end.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: One of those who has come forward is 24 year old anthropology graduate Yvette Dolibera (phonetic). Two days ago she walked into the military police station with information on 10 grave sites. She's part of a group of 8 students who've set up their own East Timorese Human Rights Commission. [Comment: Single-handedly doing more than the entire United Nations.]

In an abandoned house in Dili, these students are doing the work UN special investigators should have been doing weeks ago. They stayed in the hills around Dili while many of their families fled to West Timor. Now, with no money and few resources beyond two old typewriters, Yvette and her friends have identified 136 bodies in Dili alone, and 200 gravesites across the Region.

YVETTE DOLIBERA: We stayed and we hide in hills. I know and I see every day what's happened. Violence against women. We don't have medicine to give to child and to give something to refugees, everything. And I know that we have a senna tea but in that times they don't do nothing.

hey all talk, talk and talk and have meetings. That's all ... I think we're like our young people. We realise that we don't have nothing. We don't have computer, we don't have paper and we just have a spirit.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: So why are you doing this? What is driving you in your heart?

YVETTE DOLIBERA: Because I love people so much and I don't want to quiet if I saw something happen to them. I want to fight against bad things, or something. United Nations give command to them. They don't know the area, okay?

There are Westerners people. We know that we know more than that ... than them. Okay, we must give the information to them because they come to here not working for themselves but it's working for us. We just help them.

RAPHAEL EPSTEIN: Already this week Interfet and the United States have criticised the UN for the slow deployment of their special investigators. Now Interfet says the first group of them will arrive on the weekend.

In Dili, East Timor, this is Raphael Epstein for PM.

"Amnesty Team Heads to East Timor"

ABC (Australia) News Online, 6 November 1999

A team from Amnesty International is leaving Darwin for East Timor this weekend to gather evidence for a potential future war crimes tribunal.

The team includes a forensic scientist from Argentina, and it plans to work with local people to collect evidence before the wet season sets in.

Spokesman Des Hogan has criticised the United Nations for moving too slowly to gather war crimes evidence.

"There's a crying need for the UN to get serious about this war crimes investigation which is being hampered by foot dragging at the UN," Mr Hogan said.

"We must remember that the UN inquiry is yet to visit East Timor and yet they have to report back to the secretary general Kofi Annan by the end of December.

"The question is what can they realistically hope to cover in a comprehensive manner in a short period of weeks?" [Comment: I realize it's a rhetorical question, but one answer is: a whitewash that covers up the consequences of the U.N.'s virtual abandonment of the Timorese.]

"Women 'Raped and Abused' in West [Timor] Camps"

The Sydney Morning Herald (from Agence France-Presse), 8 November 1999

Dili: Women refugees from East Timor are being subjected to rape and abuse in camps in Indonesian West Timor, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women has warned.

"We have been receiving cases of rape and sexual slavery in the camps," Ms Radhika Coomaraswamy said in Dili on Saturday. "We are very concerned about what is happening in West Timor."

She said rape was being used as a political weapon against East Timorese women who had fled to refugee camps in West Timor.

From the UNHCR

Timor Emergency Update, 8 November 1999

WEST TIMOR

Militiamen on Monday stopped a UNHCR team at the Noelbaki camp, 20 kilometers outside Kupang, from arranging transportation for refugees wishing to return to East Timor. The team was to pick up refugees at Noelbaki to bring them to the Fatululi processing center in Kupang to register and join planes or ships returning people to East Timor. But three men wearing fatigues threatened people planning to return. UNHCR held discussions with representatives of police, the military and the governor’s office but had to pull out of the camp before dark.

UNHCR on Saturday arranged for a visit to Dili of five refugees at Noelbaki to look at the situation in East Timor. They visited their homes in Dili, met with the clergy at a local church and had a briefing on the overall situation from the commander of the International Force in East Timor. On their return to Kupang, the five refugees confirmed their intent to return home and have begun to inform others in Noelbaki about what they saw and heard in Dili. But on Monday, airlift flights from Kupang to Dili carried only 180 returnees and these were people who had been in Fatululi.

Meanwhile, UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration transported on Monday 160 refugees from Nenuk camp at Atambua, the main town in West Timor’s Belu district along the border with East Timor. Some 240 refugees had registered to go back from Nenuk, but the others did not show up at the last minute when 11 trucks came to move them to the border crossing of Motaain. Indonesian army troops escorted the returnees up to the border and the refugees then proceeded to Batoe Gade in East Timor. Earlier last month, more than 100 people joined the first overland convoy from Atambua to East Timor. UNHCR held discussions with Indonesian authorities later on Monday evening in a bid to facilitate the land movement of people wishing to go back from the Belu region, which hosts about 150,000 of the estimated 219,000 refugees in West Timor.

Also on Monday, the two ferries chartered by IOM conducted the regular run from the port of Atapupu, 20 kilometers north of Atambua, to Dili, transporting a total of 917 returnees. Returnees by ferry from Atapupu on Saturday totalled 1,374. So far, 7,542 returnees have been moved by ferry from Atapupu to Dili since repatriation started there late last month.

Harassment of UNHCR staff and returnees continued in the Atambua area. An unruly mob led by militiamen armed with machetes and spears on Monday stopped a convoy of three trucks and bus from picking up refugees at Halewen camp near the Atambua airport. Police fired several shots in the air but the militiamen continued blocking the entrance and stood their ground despite the arrival of army reinforcements. The UNHCR team decided to pull back. As the team was withdrawing, the crowd stoned the vehicles, causing minor damage. [...]

EAST TIMOR

UNHCR over the weekend sent relief supplies to Ambeno, an East Timor enclave in northern West Timor. More then 9,000 refugees were reported to have returned to the enclave from the surrounding hills in West Timor. Most of the enclave’s 50,000 residents have fled to the surrounding hills in West Timor.

"Hopes East Timorese Refugee Release First of Many"

Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 8 November 1999

MARK COLVIN: Could we be witnessing the beginning of the end of the refugee problem in West Timor after weeks of fear, disinformation and intimidation in the camps around Atambua near the East Timor border?

Two hundred and fifty people were released today and came over the border at Batugade. That's the spot where Australian and Indonesian forces exchanged fire on 10 October. Now, however, the mood seems to have changed completely and cooperation appears to be the watchword.

Our reporter, Sean Murphy, was on the border a short while ago as the refugees came across.

SEAN MURPHY: Well there's some very tired, hungry and happy people who've just finally got home to East Timor. They're being loaded on to UNHCR trucks and they're being taken home.

Two hundred and fifty people crossed the border here at Batugade - this is the main road between West Timor and East Timor, it's been virtually closed for the past month. This is the biggest repatriation so far and the international organisation for migration is hoping this is the first of many.

MARK COLVIN: Do you know how this movement has been organised? Do you know what was done to negotiate this move?

SEAN MURPHY: They organised trucks on the ground at the camps at Atambua, drove them to the border here where they were checked by INTERFET troops to make sure there were no weapons or anything, that they gave their names to the international organisation for migration and they're now on their way home.

MARK COLVIN: But I suppose what I'm asking is how did they break the log jam at all. It's been too difficult to get people out of those camps so far, why now?

SEAN MURPHY: Apparently it's because there's been a bit of a changing of the guard with the TNI here at the border. There are new commanders on the ground and they're negotiating colonel to colonel with INTERFET and that's achieved the breakthrough.

MARK COLVIN: Do you think that it has anything to do with the new government in Jakarta? Are we seeing a new mood?

SEAN MURPHY: I think obviously it has something to do with the change of government. Indonesia has enough problems without a festering sore as a refugee problem. I think they're pretty keen to get the refugees home as quickly as possible.

MARK COLVIN: So would you be - I mean 250 is just a drop in the ocean in terms of the 120,000 or so that remain in the camps around Atambua, would you expect that trickle to turn into a flood any time soon?

SEAN MURPHY: Yes, they're hoping to increase that number to 500 a day over this week. By next week up to a peak of 4,000 people per day and they expect they could repatriate the entire number within a month. [Comment: Hope for the best, but prepare for the worst.]

"Indonesia Stalls U.N. Sex Slaves Inquiries"

The Sydney Morning Herald (from the Australian Associated Press),

9 November 1999

Indonesia has refused to allow United Nations officials to visit West Timor to investigate reports of sex slavery in refugee camps, special rapporteur Radhika Coomaraswamy said yesterday.

Ms Coomaraswamy said she had evidence of sexual slavery in West Timor, where hundreds of thousands of East Timorese fled or were forcibly deported amid the violence that followed the independence vote.

Three UN special rapporteurs who recently arrived in Dili were refused access to Indonesia by the new government.

"We have no access to the camps in West Timor, but we do have access to women and witnesses who have returned from West Timor, so there is some evidence coming in," Ms Coomaraswamy said.

Special rapporteur for summary executions, Ms Asma Jahangir, who was also refused access initially, said she had written to Indonesian officials again last week but had received no response.

Ms Jahangir said evidence of killing was continuing to emerge weeks after the Australian-led multinational force, Interfet, was deployed on September 20. "According to my information two to three dead bodies are being identified per day."

Interfet's most recent death toll is 108, but its commander, Major-General Peter Cosgrove, has said the killings could have been in the hundreds.

The UN and Interfet have called for more resources to investigate crimes.

The first forensic expert arrived in East Timor last week. Previously, Interfet, whose mandate does not include investigating human rights abuses, had attempted to document the killings in East Timor.

The special rapporteur on torture, Sir Nigel Rodley, said he was sure that evidence of crimes was being damaged while investigators were delayed from being sent.

The special rapporteurs are due to publish their report on November 25.

"Migration Group Says Extent of E. Timor Refugee Crisis Known Soon"

ABC (Australia) News Online, 9 November 1999

The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) says the full extent of East Timor's refugee crisis should be known within a month.

The organisation says it has not been able to rely on Indonesian estimates of more than 250,000 displaced persons in West Timor.

The IOM's country director in West Timor is hoping the main road linking West and East Timor will be fully opened next week, allowing the tens of thousands to go home.

"Usually in a refugee crisis the numbers are inflated because the Government wants to get more aid," he said. [Note: Or wants to inflate the numbers of Timorese "accounted for" and downplay the scale of the crisis or atrocities.]

"In this one, however, it could be less than the actual number for two reasons - for minimising the incident and secondly because many people did not register with the Government when they were doing the survey, so it could actually be a larger figure."

"Militia 'Stepping Up' Attacks on Refugees"

BBC Online, 9 November 1999

[...] In East Timor, UN investigators are starting to uncover terrible human rights abuses.

"We have had testimonies from eyewitnesses of people being killed in front of them, and we have seen the sites where people have been buried," said Asma Jahangir, who is investigating summary executions.

"What we see is devastating. Two to three dead bodies are being identified per day," she said.

Ms Jahangir was speaking a day after she and two other UN investigators held their first interviews with survivors of the militia violence that swept East Timor after the independence vote.

The international peacekeeping force in East Timor (Interfet) and civilian forensic experts have so far recovered 108 remains of victims killed in the violence.

Nigel Rodley, responsible for investigating cases of torture, said: "One has to be here to see for oneself the destruction in order to grasp the horror of what happened."

He said one of the tragedies was that so few torture victims had survived their ordeal. "The ones we have met were not supposed to survive," he said.

Rape

Radhika Coomaraswamy, who is investigating violence against women, said torture and summary executions had started long before the referendum.

In earlier comments at the weekend, she said rape was being used as a political weapon against East Timorese women living in refugee camps in West Timor.

"We have been receiving cases of rape, sexual slavery in the camps. We are very concerned about what is happening in West Timor," Ms Coomaraswamy said.

The three investigators' findings will be presented to the UN General Assembly, which has the authority to establish an international war crimes tribunal.

Almost 80% of East Timorese voted for independence from Indonesia in the referendum.

"Timor Militia"

Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 10 November 1999

COMPERE: Negotiations with Indonesian soldiers across East Timor's western border are helping to increase the flow of returning refugees. But as hopes grow of a new spirit of cooperation, an ex-militia member in East Timor has told the ABC that members of the Indonesian military masqueraded as militia during the violence which terrorised the territory's population.

From Dili, Geoff Thompson reports.

GEOFF THOMPSON: Sitting on the balcony of his house in Tibar, just west of Dili, Bento Diconcensau types up his testimony for UN special investigators. In it he tells how as the village chief of Tibar he was told to join the notorious Besi Merah Putih militia or otherwise a lot of people would die. But while Bento joined the militia, he secretly hid and helped thousands of pro-independence supporters. Now he tells of life inside the Besi Merah Putih and how the Indonesian military were involved.

BENTO DICONCENSAU [via interpreter]: "They were involved, but they used militia uniforms, they didn't use military uniforms."

GEOFF THOMPSON: So there were Indonesian soldiers and Indonesian police dressing up as Besi Merah Putih militia while the violence was going on?

BENTO DICONCENSAU: "Yes, exactly."

GEOFF THOMPSON: How do you know that?

BENTO DICONCENSAU: "I know because they were Timorese Indonesian soldiers. I know them, I know them very well."

GEOFF THOMPSON: They would carry weapons and wear red and white bandannas and pretend that they were militia?

BENTO DICONCENSAU: "Yes. Actually they were Indonesian military."

GEOFF THOMPSON: Bento Diconcensau also confirms that the militia were paid.

BENTO DICONCENSAU: "There were eleven people who received money in Tibar. I found a lot of people for the militia, but I didn't take part in militia operations, so those eleven people received about 150,000 rupiah each."

GEOFF THOMPSON: Bento says that throughout the violence which racked this territory, the men of his militia were ordered to target foreign journalists.

BENTO DICONCENSAU: "They gave the command because they were frustrated and they did not want the foreigners to come here and speak about the Besi Merah Putih and Aitarak militias. They didn't want foreigners to talk about the bad things."

COMPERE: That report from Geoff Thompson.

Paul Daly,

"Militia Threats May Force Out U.N. Staff"

The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 November 1999

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees is considering withdrawing staff from parts of the Indonesian-controlled West Timor border amid rapidly increasing threats of violence from militia intent on stopping East Timorese refugees going home.

A UNHCR spokeswoman, Ms Ariane Quentier, yesterday said UN staff had been subject to 18 serious security incidents in the past 10 days, including being pelted with stones and threatened by machete- and spear-wielding militia.

She said the increased militia activity at the border town of Atambua had deterred thousands of refugees from registering with the UNHCR to go home, and potentially threatened the lives of her colleagues.

At a refugee camp near the West Timor capital, Kupang, on Monday three militia dressed as Indonesian troops (TNI) said they had orders to stop people leaving the camps.

"I believe at least 70 per cent of those people would want to go back to East Timor and we were thinking of moving over 3,000 of them," Ms Quentier said. "By the end of Monday, after those people being at the entrance, we only had two people [refugees] who left the camp and went over to the transit centre."

Indonesian police and the TNI did nothing to deter such intimidation, she said, adding that the UNHCR's representative in Jakarta had written to Indonesia's Foreign Minister "deploring that there has been no effort to intervene and arrest the perpetrators of these incidents."

"We have reached a very worried state with insecurity in Atambua, but also in Kupang," Ms Quentier said.

Asked if the UNHCR had withdrawn staff from the volatile areas, she said: "Not yet, not yet ... because we also believe that the people we are extracting, and that's the work our teams over there are doing, are also in great danger if they stay there.

"This is a race against time trying to get as many people as possible out. We might have to do it [withdraw] eventually.

"To quote our colleagues in West Timor, it is deteriorating by the day."

The UNHCR's reports of militia activity concur with Interfet fears that while East Timor is largely free of the militia, a number of the groups are rearming and training in large numbers - unhindered by the Indonesian security forces - just over the West Timor border.

But despite the escalating militia activity, at least 1,000 refugees a day continue to leave West Timor by ferry and another 200 were expected to be met by Interfet troops at the border crossing at Batugade yesterday.

Interfet's chief of staff, Colonel Mark Kelly, yesterday conceded that anti-independence militia might still be operating in the hills of East Timor.

Paul Daley,

"Evidence of Organised Killing Campaign Grows"

The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 November 1999

Evidence is emerging that Indonesia's security forces and militias orchestrated a campaign of widespread murder in East Timor in early September and hid the bodies before the arrival weeks later of international troops and observers.

Evidence of hundreds of killings in Dili alone - and possibly many more at sea - confirms the view of Australian intelligence figures that thousands, rather than hundreds, of East Timorese have died in recent months.

The international peace force in East Timor, Interfet, officially lists the number of dead at 108.

But the East Timor Human Rights Commission says that in the three weeks to October 22 it found evidence of 364 recent killings in Dili alone.

The commission says it is also investigating allegations that the Indonesian military (TNI), police and militias killed a large number of East Timorese students aboard a passenger ferry en route from Java to East Timor on September 7 and dumped their bodies at sea.

The allegation is given weight by Australian signals intelligence, which specifically indicates a large number of East Timorese students were killed at sea.

The signals intelligence also points to many other East Timorese being killed on boats or on land and then being dumped into the ocean.

The Australian intelligence community believes the discovery of more than 90 bodies on beaches on the north and south coasts of East Timor in recent weeks is further evidence that a large number of people were disposed of at sea.

"You have a situation where in some cases hands and feet were tied. In other cases bodies have wounds or were burnt," an intelligence source said.

"It leads to the conclusion that large numbers of East Timorese could be dead - some killed at sea, others killed on land, then burnt and hidden at sea.

"This takes some effort and it points to a systematic cover-up."

Asked if Interfet's official death toll was correct, the commission's general co-ordinator, Ms Isabel da costa Fereira, said: "The commission also has started investigations into killings, and from October 2 until October 22 we found 364 bodies just in Dili and [nearby towns of] Hera and Tabar.

"We are still expecting reports from our investigators who have been sent to other places to see how many might have been killed in other parts of East Timor in the same period," she said.

While Interfet has been charged with securing East Timor, its mandate does not include searching for bodies or investigating crimes.

Ms Fereira said the 364 bodies did not include those reportedly found on beaches, many of which were being buried after discovery.

Of the missing East Timorese students, she said: "On September 7 there was one boat coming from Java and Bali, and we hear that a lot of students were coming by that boat, and we hear that many of them were killed and dropped into the sea.

"But we cannot be sure of that because, of course, if they drop the bodies into the sea we are not able to find them.

"At the moment, we believe it was an operation involving TNI, the militias, the police and other military institutions."

Ms Fereira, who outlined some alleged crimes to a United Nations special rapporteur in Dili this week, urged the UN to send experts urgently to investigate allegations of rape, torture, murder and other crimes.

"It is very important that the international community come into East Timor because the evidence of crime is here now," she said.

An American doctor who runs a clinic in Dili, Dr Dan Murphy, said he had recently treated four patients who claimed to have witnessed killings at sea.

He said he believed the official estimates of how many people died are very low. "People died in every district and in sizeable numbers," he said. "I have had four patients recently who were witness to killings at sea."

Catharine Munro,

"Gusmao Angry at U.N. Aid Teams"

The Sydney Morning Herald (from Agence France-Presse),

12 November 1999

East Timorese leader Xanana Gusmao yesterday pleaded with United Nations humanitarian groups to change their approach on the ravaged territory, or leave.

Accompanied by his political deputy, Mr Leandro Issac, he said he rejected the way humanitarian aid was being delivered in East Timor.

He said he had heard many stories about UN-associated humanitarian groups "kicking out our people in Dili - that's not the way to treat our people."

"If they don't want to co-ordinate with us, because we know very well what our people need, they can leave."

He was appalled the UN wanted $US199 million ($305 million) from its donors to deliver humanitarian aid and said his people could solve the country's problems with $US50 million.

"I'm appealing to the international community. I don't agree with the character of the help. The aid doesn't reach our people. Please, we fought alone. We are the owners of this country. Please don't come as good Samaritans."

Mr Gusmao said he had suggested to UN Secretary-General Mr Kofi Annan that a 9,000-strong peacekeeping force should replace the current Interfet force. It should be used only to secure the borders and the enclave of Oecussi-Ambeno.

Resistance leader Mr Jose Ramos-Horta, who lives in Australia, yesterday announced in Portugal that he would end 24 years of exile and return to Dili on December 1.

[Comment: Sheesh, some people just don't like colonialism.]

Paul Daley,

"U.N. Stalling Holds Up Horror Inquiry"

The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 November 1999

From Christo Rei, the 27-metre statue of Jesus Christ high on a bluff at Dili's outskirts, the bright sand and gently lapping waves in the small coves below are an alluring prospect.

But the debris among the coves can reveal something resembling a kneebone or, as an Australian aid worker, Dr Andrew McNaughton, found, what appears to be part of a human neck.

Not far from here the militiamen, under the watchful eye of the Indonesian security forces, allegedly executed hundreds of people in the fortnight after the September 4 result of East Timor's autonomy ballot, before dumping their bodies in the water.

The roads on the way to the airport through Dili are lined with charred houses, shops and hotels. The few intact buildings remain so only because their owners paid corrupt Indonesian military (TNI) to declare them out of bounds to the militias that they organised, armed and controlled. From the air aboard an Interfet chopper you can gauge the extent of the destruction that was unleashed on the rest of East Timor.

Seeing such things, it is possible to reach only one conclusion: East Timor is the scene of a massive crime against humanity - and an even bigger attempt at cover-up - by Indonesia's security forces.

The Australian-led Interfet forces put on a mighty display of military hardware when they entered the world's newest country seven weeks ago, and

the militia left plenty of evidence behind.

But nobody from the international community - not the least Interfet, which has no mandate to investigate war crimes, - is seriously examining it.

"It's like you come home, the house is burnt down, grandma's been murdered and the kids have been kidnapped and you know who did it," says an American intelligence officer. "But everyone just keeps saying 'Oh how awful. She's dead, the house is burnt, the kids are gone - they should just have more kids and build another house'. I say use the evidence to drag the murderer, the arsonist, the kidnapper into court then lock his ass in jail."

But a special group appointed by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Mrs Mary Robinson, to make preliminary investigations here is yet to reach East Timor because of UN diplomatic and bureaucratic stalling.

If the group's members do get here by the end of next week, they will have just five weeks to report their conclusions on human rights abuses to the UN Secretary General, Mr Kofi Annan.

Not until that report has been considered will any systematic, forensic investigations and witness interviews begin.

Interfet has found 108 bodies in East Timor. So far this stands as the official death toll. But intelligence agencies, East Timorese human rights organisations and Interfet say the numbers are much higher.

The East Timor Human Rights Commission's general co-ordinator, Ms Isabel da costa Fereira, says the commission has found 364 bodies in Dili, Hera and Tabar.

Intelligence and military sources say it is already possible to paint a picture of systematic killing and an attempted cover-up by the TNI, its militias and the Indonesian police. They believe the killing started about two days after the ballot return on 4 September.

While UN observers and media were corralled into the UNAMET compound in Dili a few days later, the killings continued well into the second and third weeks of September.

"The bodies found [by Interfet] weren't meant to be found - that is, they were stuffed in drains, dumped in wells, buried in shallow graves and charred in burnt buildings," an intelligence figure says.

"We believe they are the ones that the Indonesians themselves missed after cleaning up what they thought were all the bodies, before Interfet arrived and while journalists had been forced out of the place."

In recent weeks more and more bodies have been found beached on East Timor's northern and southern coasts.

"There are more signs all the time of sea killings," the US intelligence officer says. "We recently received photographs of a huge croc cut open, and inside was a young woman's body. I suppose she could have been swimming. But I doubt it."

[Comment: Paul Daley is the only reporter in the English-speaking world who is on this story, which is staggering in itself. In the light of these accounts, it may be well worth re-examining the claim by an alleged "eyewitness" in September that she had seen the central police station in Dili stacked to the rooftops with corpses (see, e.g., The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 September 1999). Reporters visiting the site after INTERFET's arrival reported no evidence of such carnage (see, e.g., Maggie O'Kane's report in The Guardian on 24 September), and I myself had been inclined to dismiss it after the on-site inspections were made. But it seems clear from Daley's reports that the Indonesians made extraordinary and systematic efforts to hide and destroy evidence before they left. The police station, if it was indeed used as a centre for torture and mass killing, would surely have been a site earmarked for special clean-up.]

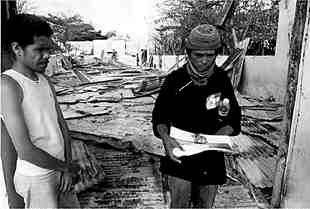

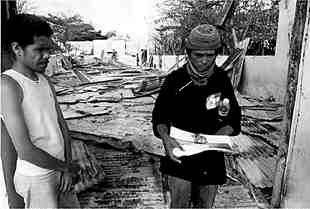

Original caption: "A key U.N. body voted on Monday in favor of

a crucial inquiry into alleged atrocities in East Timor, nearly

two months after governments, meeting in Geneva, first asked for

the probe. Two East Timorese look at ten badly charred bodies

on the back of a pickup truck in Tasi Tolu, west of Dili, on September

29 after they were found by local residents. A witness said that those

killed were bound, then hacked to death by militiamen and men in

Indonesian police uniforms before being burned.

(Darren Whiteside/Reuters)"

Evelyn Leopold,

"U.N. Panel Votes in Favor of Rights Probe in E. Timor"

Reuters dispatch, 15 November 1999

UNITED NATIONS (Reuters) - A key U.N. body voted on Monday in favor of a crucial inquiry into alleged atrocities in East Timor, nearly two months after governments, meeting in Geneva, first asked for the probe.

The vote in the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) was 27 to 10 with 11 abstentions and six members absent. The no votes came mainly from Asian and Middle East Nations, including Indonesia, India, Oman, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Vietnam and China. Russia too voted against.

None of the experts appointed by Mary Robinson, the top U.N. Human Rights official, could go to the territory until ECOSOC, the parent body of the 53-nation Geneva-based U.N. Commission on Human Rights, endorsed the inquiry.

At issue is the damage done by rampaging militia, who killed, looted and burned to protest an overwhelming vote in East Timor on Aug. 30 in favor of independence from Indonesia, which invaded the former Portuguese colony in 1975.

Nations belonging to the Geneva-based U.N. Human Rights Commission, on September 27 adopted a European Union proposal to establish the inquiry by a vote of 32-12 with six abstentions.

The delay has been a combination of politics and bureaucracy. A report due to ECOSOC took a month to arrive because of haggling among Asian states. And Robinson's financial estimates of $660 million took about the same time.

ECOSOC members in the last two weeks did not schedule a special meeting to speed up the inquiry, with Japan, which abstained on Monday, arguing that this would not be fair to the new Indonesian government.

Italy's ambassador F. Paulo Fulci, president of ECOSOC, said not many nations had pushed for a quick meeting.

Human rights activists in East Timor fear that the upcoming rainy season will wash bodies into rivers and leave little evidence to investigate.

Some special U.N. human rights experts, who do not report to ECOSOC, are in Timor to start the investigation before the Robinson team arrives. U.N. police have been marking some grave sites but very few of them were involved in the process.

The layers of decision-making at the United Nations have prompted criticism from organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch that bureaucracy and politics coincided to weaken the mission.

Secretary-General Kofi Annan has asked for Robinson's investigators to give him their conclusions by Dec. 31, although some officials expect this deadline to be extended.

Robinson on Oct. 16 announced the selection of five commissioners to conduct the probe from Nigeria, India, Papua-New Guinea and Germany, headed by Sonia Picado of Costa Rica, an experienced human rights attorney.

Typical of the arguments against the probe came from India which said procedures in Geneva were flawed, the expenses for the mission frittered away U.N. funds and that Indonesia had set up its own inquiry.

Indonesia's National Commission on Human Rights, Kommas Ham, said on November 1 that some 21 militia groups were operating in Indonesian West Timor, often holding the refugees against their will, abducting the men and abusing women.

The group said Jakarta should disband the militias, which have links to the army and police.

Adam Jones,

"East Timor: Where Are the People"?

(distributed to NGO's and media on 15 November 1999)

Youth gunned down by

Indonesian soldiers,

Dili, September 1999.

While international media have turned their attention away from East Timor, the crisis continues there at levels

that dwarf the imagination. A great deal remains unclear; indeed, what has occurred in East and West Timor is the

biggest mystery in the world. But two facts seem increasingly hard to dispute. The first is that Timorese by the

hundreds of thousands remain "unaccounted for," weeks after the arrival of United Nations (INTERFET) forces

and their alleged dispersal throughout East Timor. Second, the pattern of mass killings and disappearances that

many Timorese refugees attested to in September is now being borne out on a gruesome scale, despite systematic

attempts by the Indonesian authorities to cover their tracks.

While international media have turned their attention away from East Timor, the crisis continues there at levels

that dwarf the imagination. A great deal remains unclear; indeed, what has occurred in East and West Timor is the

biggest mystery in the world. But two facts seem increasingly hard to dispute. The first is that Timorese by the

hundreds of thousands remain "unaccounted for," weeks after the arrival of United Nations (INTERFET) forces

and their alleged dispersal throughout East Timor. Second, the pattern of mass killings and disappearances that

many Timorese refugees attested to in September is now being borne out on a gruesome scale, despite systematic

attempts by the Indonesian authorities to cover their tracks.

Consider first the missing. Reliable estimates exist of the pre-plebiscite population of East Timor: the United

Nations registered 430,000 Timorese for the vote, and demographic projections put about 50 percent of the

population below voting age. The generally-accepted total is 850,000. Of these, the proportion that has

"disappeared" simply beggars belief. In early October, Agence France-Presse cited "a senior U.N. official" who

"said ... that up to half a million people remained unaccounted for"; another U.N. official made the flip comment

that "There's 600,000 people around here someplace."

Tens of thousands of Timorese have since returned to their shattered communities, from outlying areas or from

prison camps in West Timor. But as late as November 1, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported

"hundreds of thousands of East Timorese still missing." "We certainly hope nothing terrible has happened to

them," said INTERFET chief of staff Mark Kelly. But he could offer no clues to the mystery.

Since the beginning of November, the fate of Timor's missing has virtually dropped off the world's radar screens.

But the mystery has not been solved. Entire swathes of East Timor (including the western enclave of

Oecussi/Ambino) remain a depopulated wasteland, with only a fragment of the original population daring, or able,

to return.

Many humanitarian organizations and media commentators have downplayed the issue. The presumption has been

that all or almost all of the missing Timorese are safely hiding in the hills, or in the West Timor camps.

We should certainly not underestimate the resilience of the Timorese, who after a quarter-century of Indonesian

occupation and genocide are sadly used to fleeing vicious military "sweeps." Many may indeed still be hiding. But

as the weeks pass, the argument that there are massive concentrations of Timorese still in the hills becomes

progressively harder to sustain. And if they are not in hiding, where are they?

The militia-run prison camps in West Timor are often cited as accounting for a quarter of a million or more East

Timorese. But United Nations officials have stressed that these estimates of the camps' population are provided

by the Indonesian government. They may well be inflated, by up to 100,000 people, in an attempt to secure more

humanitarian aid -- or, more ominously, because the authorities have a vested interest in pretending that tens of

thousands of Timorese are under their control who are, in fact, elsewhere. Or dead.

Which brings us to the central issue: Is it possible that a campaign of mass extermination, with tens of thousands of