- 30 June 1999

- 30 June 1999

- 30 June 1999

- 30 June 1999This is a tale, not of Kosovo, but of Bosnia. It is a story of massacre and so, alas, what is new? This is the Balkans. But it is a tale, too, of quiet heroism and of the awful dilemmas provoked by uncertainty. For the Women of Srebrenica their dilemma is simple and stark: Are their menfolk dead or not?

They are not stupid. The

odds, overwhelmingly, are

that the missing males are

indeed dead. But when you

don't know for sure, and

family members are involved,

husbands, sons, nephews,

then you hope. You hope

against hope, even after four

years.

They are not stupid. The

odds, overwhelmingly, are

that the missing males are

indeed dead. But when you

don't know for sure, and

family members are involved,

husbands, sons, nephews,

then you hope. You hope

against hope, even after four

years.

The Women no longer live in Srebrenica. They are Bosnian Muslims who fled the town in 1995 when it was captured during the Bosnian war. We met up with them in Tuzla, some 60 miles to the north-west. Bosnia is still divided, a nation state in name only. Srebrenica lies in the so-called Republika Srpska, TuzIa in the Muslim-ruled area.

They have formed an association: the Women of Srebrenica. They seek the truth. They want action. They aim to pressure the authorities, international authorities in particular, to find out exactly what did happen to the missing people, to identify bodies when they are exhumed - and quickly, to make this a priority.

It is an association of women, but there are men helping it too, men who similarly have lost relatives and want to know the truth.

A moving spirit with the

association is Hasan

Nulianovic. He is 31, and now

lives in Tuzla, a Bosnian

Muslim from Srebrenica.

Hasan is both bright and

bitter. "I hate Serbs," he told

us. "And I hate the Dutch."

He explained why.

A moving spirit with the

association is Hasan

Nulianovic. He is 31, and now

lives in Tuzla, a Bosnian

Muslim from Srebrenica.

Hasan is both bright and

bitter. "I hate Serbs," he told

us. "And I hate the Dutch."

He explained why.

In 1995 he was working as an interpreter in Srebrenica with the Dutch battalion, part of the United Nations force in Bosnia struggling to keep a non-existent peace. The town's population was two-thirds Muslim, one-third Serbian.

Srebrenica had been named a "safe haven" by the UN Security Council, but member nations had declined to provide enough troops to make sense of their declaration. The town was packed with Muslim refugees.

In July the Bosnian Serbs took the town. Hasan got his parents and younger brother into the Dutch base where he worked - to join five or six thousand other refugees, who thought they'd been given sanctuary. The Dutch, admittedly few in number, ratted on the deal. The black day was July 13th, a Thursday.

"The Dutch ordered those inside the camp to leave the camp," Hasan told us. "Serbs were standing at the gate together with Dutch soldiers. I begged the Dutch to save my brother, by allowing him to stay on the base. But everyone was thrown out of the base. My parents and my brother - I saw them for the last time crossing through the gate. Then the Serbs took them away."

Hasan knows now that his mother was murdered. A Serb has told him as much.

"I thanked him for the information because at least I know that she is dead now."

It is the not knowing that leaves people in a false world, in a limbo of confusion and hope.

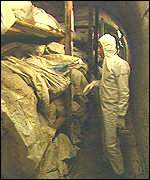

In Tuzla there is a funeral parlour, called the Memorial Centre, a grim spot. Stored there, topsy-turvy, are 3,000 bodies. Some are kept refrigerated, most are not. They are victims of the Srebrenica massacre. Almost all are unidentified.

Why, still, four years on? The

process of identification is

painfully slow. A foreign

pathologist told the Women

of Srebrenica at a special Tuzla meeting: "This work is

going to go on for many years." And there are thousands

more Srebrenica citizens still unaccounted for.

Why, still, four years on? The

process of identification is

painfully slow. A foreign

pathologist told the Women

of Srebrenica at a special Tuzla meeting: "This work is

going to go on for many years." And there are thousands

more Srebrenica citizens still unaccounted for.

Almasa Alic is one of the Women of Srebrenica. She is a lady of remarkable resilience who lives with her one surviving son. She is filled with the hope that by some miracle, her missing husband and elder son may still be alive.

"I still cherish that hope, " she told us, "because they are with me every moment of the day. I am looking for them. And no-one wants to tell the truth." Mrs Alic had the courage to visit the gruesome Memorial Centre, with its racks of rotting remains.

"I summoned the strength to go and see every bone, to open every bag, but they just weren't there."

Investigators from the Hague Tribunal, seeking to document the Srebrenica massacre, have exhumed dozens of mass graves, but their interest ends there. They are not concerned to identify individual bodies they dig up.

Mrs Alic and Hasan Nuhanovic are not fools, far from it. The International Red Cross says the Serbs hold no Muslim prisoners, that the missing are dead. "But," says Hasan, "it is possible that somewhere in the Republika Srpska, or in Yugoslavia - more likely in Yugoslavia - there are people who are still alive."

If you don't know, you dream. Hope springs eternal in the human breast. What is needed is the truth, however grim.

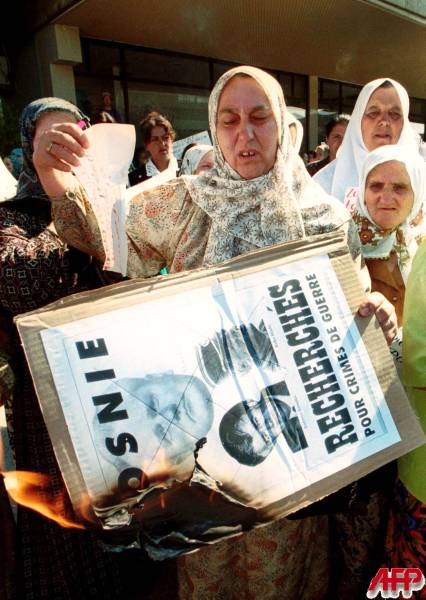

SARAJEVO, BOSNIA-HERCEGOVINA, 11-JUL-1999: A Moslem woman burns a

placard with images of Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, former

Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic and his army commander Ratko

Mladic over the words, "wanted for war crimes", during a protest by

several hundred Moslem women July 11 1999 in Sarajevo. The group

gathered in front of the UN mission offices to protest the slow

investigation of a massacre that took place exactly four years ago.

Roughly eight thousand Moslem men are believed to have been executed

in Srebrenica which had been a UN-proclaimed "safe-zone" before Serb

forces overran it in July 1995. [Photo by Elvis Barukcic, AFP]

SARAJEVO, BOSNIA-HERCEGOVINA, 11-JUL-1999: A Moslem woman burns a

placard with images of Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, former

Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic and his army commander Ratko

Mladic over the words, "wanted for war crimes", during a protest by

several hundred Moslem women July 11 1999 in Sarajevo. The group

gathered in front of the UN mission offices to protest the slow

investigation of a massacre that took place exactly four years ago.

Roughly eight thousand Moslem men are believed to have been executed

in Srebrenica which had been a UN-proclaimed "safe-zone" before Serb

forces overran it in July 1995. [Photo by Elvis Barukcic, AFP]