Un Paso Más:

Cuban Dispatches, 1998

by Adam Jones

All photographs by the author.

[N.B.: If you want to print the file and the photographs with it,

give them a few moments to download fully.]

The following is an account of an independent journey through Cuba

in August 1998. The dispatches were written as group e-mails for friends,

family, and students; some edits and additions were made subsequently,

but I have not altered the basic tone or epistolary format. Certain names

and identifying details have been changed to protect those who shared their

lives and views so openly with me. Acknowledgment should be made of two

books, Susan Eckstein's Back from the Future: Cuba under Castro

and David Stanley's Cuba Travel Survival Kit, published by Lonely Planet (hereafter, LP). Both proved indispensable sources of statistics

and background information. Unless otherwise indicated, all dollar figures

given are in U.S. currency.

Havana - Tuesday, 5 August 1998

I think so, anyway. It's all been a bit of a blur.

It began with a glitch-ridden day of travel, after an uncomfortable

night and early morning passed in the Guadalajara airport ... where I arrived only after a half-hour lugging of my bags to the old bus station

downtown. The driver took things at a brisk pace throughout, screamed into

the airport, around the ring road in front of the terminal, out the other

side, back down the highway ... "Hey!" I charged up to the front, but the

driver was so in the zone that it took him another half-kilometre or so

to actually pull over, explaining that he only stopped if someone wanted

to board or get off. I hauled my bags out and back up the road to the terminal

building under the watchful, slightly mocking gazes of the Mexican passengers.

Guadalajara Airport itself rated about three out of ten on my scale

of international airports, as a place to crash. (The more restful kind

of "crash," I hasten to add.) It had chairs, and the authorities didn't

turf me out at some ungodly hour of the night, or otherwise harass me.

I docked it a notch, though, for the mosquitoes, who feasted on the tender

flesh of my hands whenever I could manage to put myself to sleep - sprawled

over two chairs and my luggage.

At around 4 a.m. I moved through to the departure lounge. This feint didn't

shake the mosquitoes, who circled overhead like buzzards. The flight, I was told,

was delayed 25 minutes. "But please don't worry. That will still give you

half an hour to make your connection in Mexico City." I began to feel vague

presentiments of doom, but managed to suppress them all the way to La

Capital. We landed at Mexico City Airport at 6:30 a.m., with plenty

of time to catch my Havana flight. We coasted comfortably towards the terminal

building. And then we stopped. For five minutes. Getting edgy. The announcement:

"We're waiting for our bay to be prepared. We anticipate another eight

or ten minutes." Add five for Latin time, and I was in big trouble.

I stressed this out until finally, at around seven, we docked at the

terminal building. I charged down the hallway in the classic T.V.-commercial

fashion ... only to discover the flight had left right on schedule. They'd

known there were four of us on the Guadalajara flight with Havana connections;

but they'd felt it was better to send the other travelers on their way

on time. I leave you to judge the decision. Many hours later, it came to

possess a certain utilitarian logic - especially when you considered that

our bags would have had to be unloaded and reloaded. But I wasn't in the

mood to do much more than huff and protest.

The solution found was a Mexicana flight to Cancún leaving two

hours later, with a quick connection on to Havana, arriving about three

hours later than originally planned. As compensation, I stole another hour's

sleep in the waiting lounge. And as it transpired, I finally got a glimpse

of the Yucatán peninsula, which surprised me with its densely-forested

terrain even after reading descriptions of the landscape in The Caste

War of Yucatan, about the Mayan uprisings there in the mid-nineteenth-century.(1)

After an hour or so in the Las Vegas-y Cancún airport, surrounded

by North American beach bums in various stages of undress and inebriation,

I caught the Aerocaribe flight to Havana. Astonishingly, this took only

45 minutes - we were barely out over open sea before we were flying over

the west coast of Cuba. Somehow the geographical proximity hadn't registered

when I scanned the maps.

From here on the logistics began to go much more smoothly. I made it

through Cuban customs with only a few friendly questions. The Cubatur bus

outside had expected me on the earlier flight, which caused some brief

discussion; but then we were buzzing off down the highway to Havana. I

tried to drink in the roadside scenery with my eyes. Our route took us

through the heart of Miramar, the ritzy outlying district that's home to

most of the foreign embassies and diplomatic residences in Havana, many

of them housed in spectacular 19th and early 20th-century

mansions. It was a brilliantly sunny afternoon. The Caribbean was visible

as a bold stripe on the horizon, and I saw the first few Cuban flags fluttering

red, white and blue in the breeze.(2)

By the time the Cubatur van pulled up at the Hotel Capri, I was the

only person left aboard. A few other passengers had disembarked at the

anonymous-looking hotel strip much further from the centre of the action.

I'd taken some care, though, to book a hotel on the eastern edge of Vedado,

bordering Central Havana, with the famous Old City (Habana Vieja) ten minutes'

or so brisk walk away.

After a blessed shower, shave, and change of apparel, I transported

myself by elevator to the 17th floor of the Hotel Capri. The

Capri before the 1959 revolution was the preferred hangout of mafiosi

bosses like "Lucky" Luciano and Meyer Lansky.(3)

Its lookout point, adjacent to the rooftop pool, offered a spectacular

view: the whole sweep of Havana and its seashore, west towards the Playa

and Mariano districts, east towards the Old City and the massive fortresses

at the entrance to the harbour.

I was running on about three hours' sleep, but after the delays of the

day I was anxious to hit the streets. I headed out into the blast-furnace

heat of late afternoon. The basic geography of Havana I had in mind from

the couple of days I spent here in 1993 (based at the beach resorts of

Playas del Este, a few kilometres east of the city). But my recollection

was comfortably hazy. I wandered almost arbitrarily along La Rampa (23rd

street) and into the heart of Vedado. I was beginning my explorations as

the working day ended and the social hours began. There were people queuing

to fill plastic bottles from a large tanker - I thought at first potable

water, but learned later that a kind of refresco, or soft drink,

was being sold for one Cuban peso per 1.5-litre bottle. That's about five

cents in U.S.-dollar terms - but not an insignificant amount for the majority

of the population that has only pesos, as I'll discuss shortly.

Couples and singles were strolling in the parks and lounging on street-corners.

I spotted a number of well-endowed women with halter tops rendered distractingly

translucent by sweat. There was a lot of recorded music blasting, interspersed

with snatches of live performance from the occasional rehearsal-session

or small-scale concert. Kids played soccer and baseball with whatever implements

were at hand. The vitality of the street-life, even without the normal

commercial-and-neon dimension that figured elsewhere in the Third World,

was overwhelming. It was also enormously energizing.

There was food to be considered. I'd expected this to be a serious hassle

in Cuba. I'd ordered the breakfast plan at the Hotel Capri, nothing more.

That sent me to the street food being sold for moneda nacional -

the national currency, the peso. Okay, take a deep breath.

There are three kinds of currency circulating in Cuba these days. The

moneda nacional is the one people are officially paid with. The

U.S. dollar, possession and circulation of which was finally legalized

in September 1993, is the most highly-prized currency. Its partner is the

convertible peso, tied to the U.S. dollar and interchangeable with it.

The dollar and peso economies are two different worlds. Granted, the

moneda nacional has recovered against the U.S. dollar since the

terrible days of the early 1990s, when the exchange rate reached 120 to

1, so that ordinary Cubans were making about $2 a month in hard-currency

terms. Today the rate is about 20 to the dollar (around where Canadian

currency stands these days, from what I've been hearing!). The change has

underpinned a degree of economic recovery, though it is still tentative

and of recent vintage.

To the extent that the traveler is able to operate in the peso economy,

which is not very far, Cuba is a cheap country. At a certain point, though,

the state demands payment in U.S. dollars. The commercial landscape at

street-level is thus an intricate network of signs and codes telling the

consumer what is available and which currency will access it. When I finally

took a break from my street-roaming and paused for sustenance, it was at

a little street-stall selling ham sandwiches and a kind of pale, fruity-tasting

refresco. Problem was, I had a fair number of U.S. dollars, but none of

the moneda nacional - and this was a peso stall. It wasn't a predicament

many Cubans would have sympathized with, but it was a hitch nonetheless.

Fortunately, a young guy who'd stopped by for a bite was happy enough to

change a couple of dollars with me - two, literally. Now I had forty Cuban

pesos to my name. That was enough for a hefty and sufficiently-edible sandwich,

which cost me a dollar - a good deal for me, but a fair chunk of a monthly

income for anyone paid in pesos.

Much revived, I wandered into the heart of Central Havana. There I found

myself outside a corner bar - just a stand-up counter, with a guy behind

it selling rum by the glass. I mean the glass - four or five ounces

each. I'd understood that many bars were built at the intersection point

of the dollar and peso economies: Cubans paid in pesos, and foreigners

the dollar equivalent at a one-to-one exchange rate. Thus, when

I asked the barman how much a glass cost, I was expecting an answer in

U.S. currency. "Five," he said. "Dollars??" It seemed a little steep, although

they were big glasses ... "Pesos," he responded promptly. That suddenly

made things a whole lot more practicable.

And so it was that I came to prop up a corner of the bar, and found

myself in conversation with Andrés. He was a serving military officer,

52 years of age, who looked a lot like Harry Belafonte. He said he'd heard

it before.

Andrés had two companions who were fairly well stuck into the

rum already, and a lot harder to understand when they spoke. He himself

held his liquor well, articulating his thoughts about as carefully and

clearly as this second-language Spanish-speaker, running on insufficient

sleep, could have hoped for. He had nice things to say about Canada, which

has a reputation in Cuba as one of two countries (the other is Mexico)

that refused to join the U.S. campaign of isolation and embargo against

the island, choosing instead to maintain normal and even warm relations

with Cuba.

Andrés told me too about his life in the military. It earned

him, he said, 218 pesos a month - around $10. But he liked the country

and the revolution; the problems were not the government's fault. He invited

me to visit his house - I will try to stop by there tonight (two days later),

if I can get my move from the Hotel Capri into private housing sorted out

in time.

With a couple of rums in my belly I wandered the streets until the Cubans

went to bed, which was at a civilized hour - 10:30 or 11:00. Heading back

to the hotel, I found myself taking a short-cut through a small park not

far from the imposing gates of the University of Havana. There, I bumped

into three young people splayed across a bench. They were Oscar, Francesca

and - Eva. That led to an inevitable onslaught of Adam-and-Eve jokes, but

when the merriment had run its course, we settled into conversation. Francesca,

a very young Naomi Campbell lookalike, was pursuing a modeling career;

she already cultivated the supermodel's frail demeanour. Eva, intelligent,

was studying film; Oscar, a young Black guy, clearly lived to party, and

seemed to have every intention of doing so tonight. I didn't have the energy.

But we agreed to meet the following day at the monument commemorating the

U.S.S. Maine - on the Malecón, the seaside promenade that

winds along the periphery of the Old City, Central Havana, and Vedado.(4)

Finally it was back to the splendour of the Hotel Capri. Well, let's

not get carried away. The carpeting had seen better days. The taps squeaked

when you turned them, and the furnishings were worn. But I had air-con

and a killer 12th-floor view over the city. The TV received

CNN and a special closed-circuit channel run by the Cuban government for

foreigners only. Transported to my little hermetic tourist's world, I lay

back on clean sheets, listened to the air-conditioner hum (too audibly),

and lost consciousness for a while.

Havana - Thursday, 7 August 1998

Things are moving so quickly - experiences and sensations piling onto one

another - that it's hard to keep these dispatches up to date. But that's

not how it began on Tuesday morning.

I figure if you're going to sit in the lap of luxury for three or four

days, you might as well take time to appreciate it; also, the trek the

previous evening had given me a couple of whacking great blood blisters

that I wanted to be kind to. And so I tumbled out of bed and down to fill

up on the hotel's buffet breakfast, which, it must be said, was pretty

bad - sometimes instructively so.

The fruit trays were laden with two different kinds of grapefruit, along

with mango and watermelon. Relatively few people tucked into the grapefruit

(don't look at me - I was right in there). They stocked up instead on watermelon

and mango. But that didn't affect the pace at which the different items

were restocked. This stayed uniform, with the result that the mango-and-watermelon

crowd seemed eternally to be out of luck. Apart from the aforementioned

fruit, the buffet choice was: roasted carrots (huh?), diced potatoes -

but just diced, not fried or hash-browned or anything intricate like that;

boiled eggs; croissants like hockey pucks; and omelettes churned out to

order by an overworked chef, for which the available ingredients were:

ham and cheese. Sometimes there wasn't any cheese. It was also interesting

to note that you could sit yourself down at a table littered with the refuse

of former diners, and quite placidly eat your entire meal without anybody

bothering to clear away the detritus.

Digging into this odd and mostly unappetizing cuisine was about as exploratory

as I got for a while. I spent the rest of the morning and afternoon napping,

watching CNN, and enjoying the 12th-floor view. Around 3 p.m.

I got my act together sufficiently to shower and head out into the streets,

pulsing with afternoon heat. I wandered down through the Old City, which

I will never get enough of. "The largest Spanish colonial complex in the

Americas," LP calls it. The closest thing I've seen to it is the

Old City of Cartagena in Colombia, which is more shiningly restored, but

barely a neighbourhood compared with Havana's run-down but much more extensive

offerings.

Then it was back to the Maine monument to meet Oscar, my friend

from the previous night. We headed immediately to the Old City. Oscar said

he wanted to show me "the nicest paintings in Cuba."

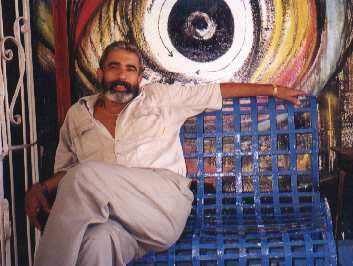

Along the Callejón Hamel

They were part of what I was told is the second-largest piece of street

art in the world: an entire alley, including buildings, in the Callejón

Hamel, a nondescript lane in Central Havana covered with a long multimedia

creation by an artist named Salvador - who just happens to have his studio

in the Callejón. Salvador's work explores the influence of African

culture on Cuban society and especially the syncretic religion of Santería,

which derives from the roots many Cubans have in the Yoriba and Ibo nations

of West Africa. It would be pointless to describe the art in much greater

detail, but it was spectacular. I was glad to shake Salvador's hand and

promise to return to take photos.

They were part of what I was told is the second-largest piece of street

art in the world: an entire alley, including buildings, in the Callejón

Hamel, a nondescript lane in Central Havana covered with a long multimedia

creation by an artist named Salvador - who just happens to have his studio

in the Callejón. Salvador's work explores the influence of African

culture on Cuban society and especially the syncretic religion of Santería,

which derives from the roots many Cubans have in the Yoriba and Ibo nations

of West Africa. It would be pointless to describe the art in much greater

detail, but it was spectacular. I was glad to shake Salvador's hand and

promise to return to take photos.

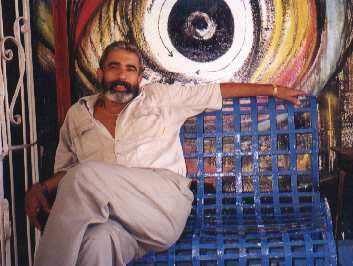

The Artist Presently Known As Salvador

Oscar

led me over to the market, where I bought us a couple of huge, unbelievable

mangoes - 12 pesos for both, a little over fifty cents. Oscar showed me

how to peel the mango with my teeth and then snuffle down in the fleshy

fruit, emerging with the entire lower half of my face (and unfortunately

a fair area of my T-shirt) smeared with juice.

Oscar

led me over to the market, where I bought us a couple of huge, unbelievable

mangoes - 12 pesos for both, a little over fifty cents. Oscar showed me

how to peel the mango with my teeth and then snuffle down in the fleshy

fruit, emerging with the entire lower half of my face (and unfortunately

a fair area of my T-shirt) smeared with juice.

We'd been leaving a trail of mango skin along the streets, and when

I'd had about enough, I looked for a place to toss the remainder. Oscar

was apparently looking for a place, too; at least, he cradled what was

left of his mango ruminatively in his hand. And he kept it there. Good

thing I didn't toss the rest of that fruit. This was by no means an everyday

treat in today's Cuba, and Oscar was taking the remainder home, to share

with his family and girlfriend.

At Oscar's place in Central Havana, in the tiny loft he'd adorned with

spacey graphics and lots of Rastafarian iconography, I met his companion,

Yasmin, and her friend Joanka (pronounced Ho-AHN-ka). Examples,

here, of the exotic names that abound in Cuba. The country's "proletarian

internationalism" - its military involvements in Angola and Ethiopia, the

work-and-study exchanges with the former Soviet bloc, and the sending

of tens of thousands of teachers and health-care workers overseas - have

led to quite a stew of nomenclature. My first night in town I'd been introduced

to a Luanda, which is both the capital of Angola and a very nice name for

a woman. Yasmin's name was bestowed on her by parents who had studied in Czechoslovakia, where they met

a lot of Arab students. Joanka, like the Katyusca I met in passing

yesterday and the Alexander whom you'll meet shortly, seemed a throwback

to the days of warm Russian-Cuban relations.

Stripped to the waist in the suffocating heat, I sat in that loft for

the next five hours or so. This was about the toughest test my Spanish

had ever faced, especially since Joanka, a fine-featured young black woman

from the east of Cuba, spoke the near-patois of the region around

Santiago de Cuba, giving me fits of incomprehension throughout. Yasmin,

bless her heart, understood my predicament well, and constantly urged Joanka

to slow down and speak more clearly. This did no good whatsoever, although

over time I began to adjust to Joanka's rhythm a little better.

Yasmin, for her part, spoke with wonderful clarity and impressive intellectual

force. Without any urging, she launched into a protracted critique of the

Cuban system - her voice rising loud enough, in the closely congested streets

of Central Havana, to be audible outside or in neighbouring houses. Joanka

echoed her criticisms at almost every turn, and added a few of her own.

Both the women were musicians - percussionists - and they joined in decrying

the stifling political and cultural atmosphere they were forced to put

up with. Cuba, said Yasmin, is encountering a basic contradiction: capitalistic

elements have been grafted onto a state-socialist system, but with no clear

indication from the government exactly which of the two directions the

country is headed in. The profusion of currencies, and payment in pesos

when people were charged for many items in dollars, well symbolized the

quandary. Castro, Yasmin said - calling him El Señor, a standard

code-word - seemed to have run out of ideas. She described the absurdity

of turning every state radio and TV channel over to five-hour speeches

from Castro, so that his words became well-nigh inescapable. Then she jokingly

pointed out the copy of Marx's Das Kapital that she'd been made

to read at university. About 150 pages were missing from the back - ripped

away, she said, to use as toilet paper.

When my laughter ebbed, Yasmin suddenly - again with no urging - launched

into a paean to Fidel. He was the guardian of Cuba's independence, she

said: a world-class leader who had given Cuba disproportionate visibility

internationally; an enormously popular symbol among the poor of Latin America

and the Caribbean. Castro, as we spoke, was winding up a three-country

tour of Caribbean states, concluding with Grenada - which the U.S. invaded

in 1983, allegedly to stave off Cuban intervention. The Cubans living there

(including the dozens killed during the invasion) were construction workers,

building an international runway supervised by a British consortium. The

fact that Grenadians held no grudge towards Cuba was evident from the popular

welcome Castro had received, comparable in its warmth to the fiesta-like

treatment he'd gotten earlier in Jamaica.

Both Yasmin and Joanka, then, found things to like in Castro's leadership

and the political system more generally. They spoke favourably of a number

of senior ministers (all of whom have a lot more visibility and durability

than their Canadian counterparts). Ricardo Alarcón, Castro's most

likely successor, came in for a good deal of praise: a capable, moderate,

innovative person, said Yasmin.(5) But the

frustration and sometimes humiliation of living outside the dollar economy,

while Cubans with relatives who'd abandoned the revolution for the U.S.

lived like kings, was their biggest source of hardship. "It just pushes

you to prostitute yourself," said Yasmin. Indeed: if you don't work directly

in the tourist economy, what other way is there to get dollars? This is

one reason the institution of the casa particular (private home)

is so important - it gives Cubans the right to rent out rooms in their

dwellings to travelers who can't pay luxury-hotel rates. The state's ambivalent

attitude towards the institution, and the heavy tax load imposed on renters,

is a source of irritation for many ordinary citizens.

The conversation stretched until 10:30 at night. By then I could hardly

get any more Spanish syllables out of my mouth, and we broke off. Joanka

walked me most of the way home: her house lay not far from the Capri. We

both felt a little uncomfortable with the knowing glances we received in

the street. A foreign visitor strolling with a young, elegantly-proportioned

black woman meant only one thing to most Havana residents. Prostitution

was, if anything, more pervasive and above-ground than the last time I

was here, in 1993. At a guess, anywhere up to 50 percent of the tourists

in Cuba were there for the cheap sex.

Saturday, 7 August 1998

Where am I up to now - Tuesday? The pace remains dizzying. Only in the

last 24 hours or so have I begun to feel settled - or resettled. That's

right: this is the first dispatch to come to you live from a casa particular.

For independent travelers on a limited budget, the casa particular

is about the only option in Cuba. The standards and facilities vary widely,

from what I've been told. Mine is near the basic end of the spectrum. It

is located in Central Havana, close to the heart of the Old City. Almost

automatically, this means it is in a run-down building. This one, though,

feels fairly safe structurally - as long as you don't live on the second

floor (a different residence), where the rotted railing looks as though

it wouldn't support the weight of a toddler.

I, fortunately, am on the ground floor - in the care of a delightful

woman named Felicia. As I talked to Felicia, and with the dizzying profusion

of relatives, friends, and customers who stopped by, I learned more about

her set-up.

Felicia responded to the economic crisis of the early '90s by opening

a paladar - a private restaurant - in her living room. Twice she

operated it; twice she was closed down by the authorities, who are jealous

of the official monopoly they enjoy in the culinary field as well as hotel

accommodation. And running a restaurant is a bitch in Cuba. You have to

have solid sources of supply beyond the state channels, which are undependable;

you have to work very hard; and there's the risk of a crackdown by the

authorities. Running a casa particular doesn't remove this risk,

but the work is easier - all you have to do, usually, is turf one of your

family members out of their bed whenever a foreigner needs a room, plant

them elsewhere in the house or with friends, and rake in a massive amount

of money by Cuban standards. I'm paying US $12 a night to Felicia, which

is better than I expected to do here, but still a month-and-a-half's income

for the average Cuban. The price would likely have been higher if Felicia

had chosen to register her place with the authorities and pay tax on her

income. To do so, though, would risk ruin. The government took a particularly

dim view of casas particulares in tourist areas, where the state

hotels were concentrated. So you could easily end up paying hundreds of

dollars in monthly taxes in Central Havana, whether you rented out the

room or not. I didn't feel a lot of guilt about helping Felicia evade

the taxes. The government had charged me $25 just to enter Cuba, and would

hit me up for another $20 when I left. It was also determined to charge

me in dollars for train-fares that Cubans could pay in pesos - at a one-to-one

exchange rate. I figured I would be pouring enough greenbacks into the

state's coffers during the trip to take refuge in the underground economy

now and then.

For my daily $12 ($4 of which, I discover later, goes to Oscar as a

commission for leading me to the room), I got a comfortable bed with clean

sheets, a good fan, a separate bathroom, and a sitting-and-kitchen area

which I don't use. My chambers had two separate entrances, both locked.

Well, I suppose they should have been locked, according to the most

elementary traveler's precautions. But frankly, after the first few hours,

I didn't bother. If you knew Cuba, and the house Felicia kept, this might

make more sense. Crime and theft are far from unknown in Havana: I have

been repeatedly cautioned (and have repeatedly ignored cautions) to wear

my shoulder-bag with the strap across my chest, to guard against bicycle-riding

thieves who stage snatch-and-grabs in the street. (Necessity in the face

of austerity, perhaps. Elsewhere in Latin America, the thieves would be

on motorbikes.) Bag-snatchers aside, there is no doubt Cuba is an extraordinarily

safe society in terms of physical security. And the home seems almost sacrosanct:

I've not heard a report of a Cuban who'd experienced a break-and-enter,

though it can happen. This is one reason, I've decided, why the street-life

in Havana remains so vibrant. The membrane separating domestic from public

realms is porous. As for the interior space, I decided to take Felicia

at her word that I had nothing to fear from her family, friends, or visitors.

She seemed to have things well in hand.

Another thing she often had in hand was a customer's hair. That was

the official function of her establishment - a beauty-salon. Stepping out

into the common area usually meant encountering a neighbourhood local seated

in a wooden chair, getting a cut or a perm. (They head over to the common

sink to rinse off; there was one fifties-style hair-dryer away in the corner).

While Felicia was busy clipping and styling, the black-and-white TV blared

the afternoon telenovela (soap opera) to a handful of glazed or

galvanized viewers.

The late afternoon and early evenings at Felicia's were spent around

a common table, together with Marcos, a Spanish guy who'd been staying

on-and-off with Felicia for four years now. Yes - four years. To

hear him tell it (in a fine Castilian accent), he'd worked various jobs

in Spain, from fishing to mountain-rescue, then finally opened a supermarket

and become independently wealthy - wealthy enough, he said, to retire and

live off the proceeds, at the young age of 35. He headed down to the foreign

division of one of the big state banks every week or two, swiped his credit-card

through, collected his money, and headed back to pass another day (or rather

another night) in Havana. Since the authorities required him to leave the

country every two months to renew his visa, he had to rouse himself on

occasion. Otherwise, his ardent and explicitly-stated determination in

life was to do as little as possible. He had been back here for about five

weeks, and still hadn't gotten around to calling his mother, as he'd been

meaning to do from the first days he arrived. "There's just no time, my

friend."

With his years of experience in Havana, Marcos was an excellent source

of information, and a good guy to knock back a few beers with. His rhythm,

though, was built around all-night sessions in the local clubs and restaurants

- and, above all, on the Malecón. There, around four or four-thirty

in the afternoon, he more or less began his day, exchanging glances and

words with strolling Cuban women. "I am crazy for the women here,"

he said. It tended to keep him out until about eight o'clock in the morning

- the Malecón hummed until five or six - and he warned me that he

would not let me leave until I'd seen the sun coming up behind the Castillo

del Morro, the famous fortress at the mouth of Havana harbour. I told him

I would probably get up early rather than stay up late - among other things,

I have a lifelong aversion to discothèques. But it sounded like

a fine idea.

On Wednesday afternoon, Oscar took me to a beautifully-restored mansion

that houses the Union of Cuban Artists and Writers (UNEAC). A half-dozen

or so up-and-coming Cuban groups were putting on a concert. For Oscar and

his companions, the admission was ten Cuban pesos (fifty cents US at the

current rates); for me, five dollars. I had to concede there was a certain

democratic dimension to this. It meant the audience consisted of dollar-bearing

foreigners and peso-paying Cubans, rather than degenerating into a tourist

ghetto. And any reservations I might have had about the entry fee were

blown out the window when the music started. It was a marvelous venue,

the crowd sitting at tables in the courtyard of this 19th-century mansion,

with the stage set up on the steps. And it was a marvelously diverse selection

of music. Things started with a couple of visiting U.S. singers - part

of a cultural exchange - who sang very creditably in Spanish. Things didn't

really begin to cook, though, until the first Cuban group took the stage;

and the concert hit the stratosphere with the charming Brazilian guitarist

who followed them. It was the first time I'd heard bossa nova sung

with such shading and detail. If I told you he closed his set with "The

Girl from Ipanema," the most famous Brazilian pop song, you might laugh

- but only if you'd never heard it sung as sweetly and wistfully as on

this night.

Brazilian guitarist, Havana

The last lineup of the evening featured a group that had already entertained

us with some stinging acoustic blues, joined by everyone who felt like

getting up on stage. The show-closer was a powerhouse version of Cuba's

most famous song, "Guantanamera." Again, this had the potential for kitsch;

but it was sung as a slow blues, which allowed all the majesty of the lyrics

to emerge:

The last lineup of the evening featured a group that had already entertained

us with some stinging acoustic blues, joined by everyone who felt like

getting up on stage. The show-closer was a powerhouse version of Cuba's

most famous song, "Guantanamera." Again, this had the potential for kitsch;

but it was sung as a slow blues, which allowed all the majesty of the lyrics

to emerge:

Yo soy un hombre sincero

de donde crece la palma,

y antes de morirme quiero echar

mis versos del alma.

Con los pobres de la tierra quiero yo

mi suerte echar,

y el arroyo de la sierra me complace

mas que el mar.

I'm a sincere man

from the land of the palm tree,

and before I die I wish to sing

these heart-felt verses.

With the poor of the land I want

to share a fate,

and the mountain stream pleases me

more than the sea.

The lyrics are taken from a poem, "Versos Sencillos," written in 1891 by

Cuba's greatest nationalist figure, Jose Martí, killed in battle

against Spanish colonial forces four years later. (Cuba was a Spanish colony

for much longer than most other Latin American countries - until 1898.)

Martí's words, carefully sung, imbued the well-known chorus that

followed with a special note of celebration and liberation. As sung by

a dozen or so full-throated individuals on stage and most of the audience

as well, it was an unforgettable moment.

The unifying fount of this diverse music, it seemed to me, was West

Africa. Bossa nova, blues, son (Cuban country music), salsa

- they were all traceable to the slave ships that dragged Africa to America

hundreds of years ago (until 1865 in Cuba). Cuba keeps its African connection

alive mainly through its music, as well as through the beliefs pervading

santería religion. The Spanish influence lay in melding guitar

and melody with the percussive heart of West African sounds. Now the Cuban

synthesis itself commands a worldwide influence - not least in West Africa.

All-woman percussion band

Thursday night, too, found me briefly at a pop concert. I didn't spend

long enough to get the full flavour - I was desperately tired - but again

I witnessed the sheer joy that burst forth when nearly anyone played, sang,

or just listened to music in this country. Song is literally a life-force

in Cuba, in a way that no western culture can duplicate. Even the moments

when music stepped forward to lead western culture - say, in the

1960s - tended to have a generational character, and to highlight divisions

and rifts at the same time as they broke down certain social barriers.

In Cuba, by contrast, the tradition is universal and cross-generational.

Beyond keeping just about every musician in the country on its payroll,

the state seems to have little interest in restricting the diversity of

Cuban sounds. Rock and roll, and other "decadent" western imports,

are more tightly controlled. But much as I might criticize such cultural

constraints in Cuba, I had to admit you could go a long way musically without

ever leaving the island. Even the politicized music recorded in the 1970s

and '80s - by Silvio Rodríguez and many others - stood out, partly

because the state held musicians on a rather looser rein than many other

artists and intellectuals.

Thursday night, too, found me briefly at a pop concert. I didn't spend

long enough to get the full flavour - I was desperately tired - but again

I witnessed the sheer joy that burst forth when nearly anyone played, sang,

or just listened to music in this country. Song is literally a life-force

in Cuba, in a way that no western culture can duplicate. Even the moments

when music stepped forward to lead western culture - say, in the

1960s - tended to have a generational character, and to highlight divisions

and rifts at the same time as they broke down certain social barriers.

In Cuba, by contrast, the tradition is universal and cross-generational.

Beyond keeping just about every musician in the country on its payroll,

the state seems to have little interest in restricting the diversity of

Cuban sounds. Rock and roll, and other "decadent" western imports,

are more tightly controlled. But much as I might criticize such cultural

constraints in Cuba, I had to admit you could go a long way musically without

ever leaving the island. Even the politicized music recorded in the 1970s

and '80s - by Silvio Rodríguez and many others - stood out, partly

because the state held musicians on a rather looser rein than many other

artists and intellectuals.

The greyness afflicting other parts of Cuban culture, though, was hard

to avoid. The mass media, in particular, were already seeming terribly

dreary. Granma, the official organ of the Cuban Communist Party

(and the only national daily newspaper), was now running eight pages a

day instead of the four it was limited to at the height of the período

especial ("Special Period") in 1992-93. Granma would probably

tell you if the outside world suddenly exploded. Otherwise, though, there

wasn't much international news, except to the extent that Fidel was hitting

the road.

As for television, I'd been hearing it more than watching it, given

my bedroom's proximity to Felicia's noisy set. I didn't actually plant

myself in front of it until last night, when I managed to drop by the house

of Andrés and his partner, Carmen. Do you remember Andrés,

the military officer from that neighbourhood bar on my first night in Havana?

He lived, I learned, at street-level on Avenida Sol in the Old City, close

to the imposing Capitolio building. When I arrived, the TV was blaring

a Colombian soap opera, Las Aguas Mansas, dubbed into Spanish. Such

programming is massively popular in Cuba (as all over Latin America), and

Andrés seemed as rapt a viewer as any. I asked him whether he was

a fan, and this dedicated military man smiled a broad smile and responded,

"Well, there's not a hell of a lot else to watch." Surely, I asked, sometimes

they showed movies? Andrés brightened quickly. True, he said. In

fact, one of the two TV channels in the country would shortly be broadcasting

the first of a series of old Tarzan flicks.

It was a great pleasure to meet Carmen: a large, extremely buoyant woman

topped with an impressive tower of silver-grey hair. As it transpired,

I was the first foreigner she and Andrés had ever welcomed in their

home. She commemorated the event by offering me a couple of glasses of

chilled, delicious mango shake, which I drank gratefully in the still-brutal

evening heat. Two fans were going: one a tiny, dusty antique, lacking even

a screen; the other a modern, free-standing model of the kind I had in

Felicia's room. Such items were available in Cuba, Carmen told me, but

only in dollars. Eighteen of them for the fan - and Carmen's patient, protracted

explanation of how she'd collected those eighteen dollars over many months

offered another object lesson in the economic difficulties that ordinary

Cubans face. Fortunately, Carmen was able to count on a few generous friends

at her place of work who pooled some money as a present. A Cuban friend

visiting from the States kicked in the rest, and Carmen got her fan.

Carmen and Andrés

Like

the other Cubans I'd consulted on the subject, Carmen claimed things had

improved measurably in the last few years. Prices were ridiculously high

for, say, Cuban-made shampoo - ten pesos for a small bottle, about a twentieth

of her monthly income (she taught young children with special needs). But

at least there were bottles of shampoo to buy - and soap, to supplement

the absurd little bar that Cubans received as their monthly individual

allotment. (It lasted her, said Carmen, about three days.)

Like

the other Cubans I'd consulted on the subject, Carmen claimed things had

improved measurably in the last few years. Prices were ridiculously high

for, say, Cuban-made shampoo - ten pesos for a small bottle, about a twentieth

of her monthly income (she taught young children with special needs). But

at least there were bottles of shampoo to buy - and soap, to supplement

the absurd little bar that Cubans received as their monthly individual

allotment. (It lasted her, said Carmen, about three days.)

Still, it was a far cry from the halcyon days of the 1980s. Back then,

Cuba still received its six or seven billion dollars a year in subsidies

from the Soviet Union. "You could buy an entire fat chicken for ten pesos,"

Carmen remembered. "Now it costs you perhaps five or six U.S. dollars -

a hundred pesos." She found herself spending nearly the same amount - half

her salary - on cooking oil to supplement the meagre state ration. "And

today they didn't have any in the shops." Many basic foods and commodities

that she would not have thought twice about purchasing ten years ago now

had to be laboriously saved up for, or were available irregularly and/or

only with dollars, or had simply disappeared from her diet and lifestyle.

"We used to be able to go to a restaurant every now and then!"

Carmen remembered fondly the trips she'd taken to the Soviet Union as

part of a Cuban delegation. She'd even been to Moscow in winter, she said.

Their hosts had outfitted them with "boots up above your knees" to wade

through the snow; but the blanket greyness of the sky, the absence of the

twinkling Caribbean vistas, made her feel depressed. (As an aside, the

fact that many of the flights between Cuba and Eastern Europe refuelled

in Gander, Newfoundland means that a surprising number of Cubans have actually

set foot in Canada - even if only in Gander's transit lounge. Carmen described

the shiny decor and duty-free shops with evident nostalgia.)

Where visits abroad and vacations at home were once the norm, Carmen

now found her world had shrunk to her house and her place of work; she

ran nonstop from morning until midnight to meet her varied responsibilities.

From none-too-subtle signals, I sensed that Andrés, though a sweet

guy - they had been together for 31 years - was not exactly keeping up

his end of the domestic chores. Perhaps his visits to the neighbourhood

rum-stand, though fortuitous for me, seemed a waste of precious pesos in

Carmen's view. Nonetheless, she loved her work - providing services for

learning-disabled students who wouldn't have stood a chance in most other

countries of Latin America. With the resources she'd managed to scrape

together, she had appointed her home with care and taste; she sold party

decorations out the front window to bring in a little extra income. Andrés

had contributed repairs and refurbishments that kept the old house more

than livable.

Both Carmen and Andrés proclaimed their support for the revolution

- not stridently, but in the course of conversation, as it were. "Other

people around here - well, you'll have to ask them," said Carmen, not seeming

troubled that others might not share her views. I left the two of them,

feeling much revived, around 10:30 p.m. The TV had had a kind of brownout

- overheating, it seems, so that the image was only dimly visible on the

screen. A common problem with these old Russian models.

Intermezzo I: The Libreta

In a longish chat with Alexander a couple of days ago - he's the friend

of Oscar's whom I mentioned a while back, a sweet, soft-spoken young guy

- I managed to get an up-to-date breakdown of the libreta. This

is the state-rationed basket of goods (technically, the ration-book you

use to access them) which every adult Cuban receives monthly, in theory

at least. To what extent are the high prices in the markets and the dollar

shops offset by subsistence goods from the state?

The answer is, not very bloody far. According to Alexander, the libreta

consisted of:

6 pounds of rice monthly (all allotments are monthly unless otherwise

mentioned)

6 pounds of white sugar

6 pounds of raw sugar

2 pounds of chicharros (yellow beans), when available

Half a pound of salt

Half a pound of cooking oil

1 (small - hotel-style) bar of soap

1 small bun daily

2 small bags of coffee every fifteen days

6 eggs every fifteen days

A quarter-pound of chicken every three months

Half a pound of some miscellaneous commodity every three months (e.g.,

pasta, soya, an extra ration of chicken), depending on availability.

There you have it. Cuba has sugar like Canada has snow, so there's plenty

included. As for the other goods, estimates varied as to how far into the

month the libreta could be stretched. Alexander said he could make

it two weeks. Carmen found it lasted her about half as long. Either way,

when it ran out, and to supplement its meagre offerings, you were stuck

with purchases in the market. There, a single small onion would cost you

two pesos - around one percent of your monthly income; a clove of garlic

the same. A one-pound bag of rice cost five pesos; a small bag of pork

- about the only meat dependably available - 20 pesos. The quantity of

goods distributed through the libreta system has withered in the

last few years, with the state increasingly charging (though not paying

wages) at market rates. All the prices quoted are at the state-run markets.

Prices in the farmer's markets, or on the black market, are considerably

higher, and usually dollarized. But these may be the only channels available

for goods which, like lobster or cigars, are destined for export or the

tourist sector, and are therefore virtually absent from the official economy.

Milk is reserved for children under seven years of age, and nursing mothers.

Others can buy it only from those selling their allotment, or factory workers

dealing on the side.

Monday, 10 August 1998 - Havana

Newspaper seller, Havana

What this account of my time in Cuba's capital doesn't capture is the hours

and hours spent wandering the streets of Habana Vieja and Centro Habana.

This is an experience that can make your head swim, from the rank aroma

of piss and rotting fruit on most streets, the whiffs of exhaust from one

of the indestructible old gas-guzzlers of the 1950's, the hisses and urgent

whispers from the sidewalk - "Hey, man, what's your country?"; and above

all from the ferocious heat beating down on your face and the top of your

head. (Even the Cubans are feeling it - this summer, thanks to El

Niño, is hotter and drier than usual, and August is the hottest

month in Cuba anyway). ... I find myself setting out on some half-hour

mission and returning, dazed and sodden with sweat, after prowling through

backstreets and parks and along main boulevards. On a couple of occasions,

this wandering came about of necessity - trying to find food, of which

more later. Mostly, it was just getting creatively lost, and taking in

as much as I could.

What this account of my time in Cuba's capital doesn't capture is the hours

and hours spent wandering the streets of Habana Vieja and Centro Habana.

This is an experience that can make your head swim, from the rank aroma

of piss and rotting fruit on most streets, the whiffs of exhaust from one

of the indestructible old gas-guzzlers of the 1950's, the hisses and urgent

whispers from the sidewalk - "Hey, man, what's your country?"; and above

all from the ferocious heat beating down on your face and the top of your

head. (Even the Cubans are feeling it - this summer, thanks to El

Niño, is hotter and drier than usual, and August is the hottest

month in Cuba anyway). ... I find myself setting out on some half-hour

mission and returning, dazed and sodden with sweat, after prowling through

backstreets and parks and along main boulevards. On a couple of occasions,

this wandering came about of necessity - trying to find food, of which

more later. Mostly, it was just getting creatively lost, and taking in

as much as I could.

These are throng-filled days in Havana. The city is heading into the

final week of its Carnaval - originally the holiday that celebrated the

bringing-in of the harvest. In the years of cruel austerity in the early

1990s, Carnaval, both in Havana and in Santiago de Cuba (where it is allegedly

more wild), was canceled by the state. Things are still threadbare. Rather

than an array of floats, for example, the parade on Saturday night had

one big one, with a band on board (this being Cuba, it was a huge and rocking

one). It made pit-stops every fifty yards or so, blasting at the crowds

in the bleachers and lining the railings. For this and the other festivities,

the Malecón on Saturday drew perhaps forty or fifty thousand people

along its length. The police presence was heavy, and this in part might

have accounted for an atmosphere that was more milling than celebration.

There were slim pickings, on such occasions, for the average Cuban.

He or she could buy a local brew in a cardboard container at roadside,

or one of the ubiquitous funnels of peanuts sold by street-vendors. There

might be an ice cream if you lined up a few minutes - eat it fast before

it drips all over your shoes. If you wanted a seat on the grandstands along

the parade, you had to pay - I didn't bother to find out how much. Most

people sprawled out on the Malecón and on public squares and statues,

doing more or less as they would have done on non-Carnaval days, only in

greater numbers.

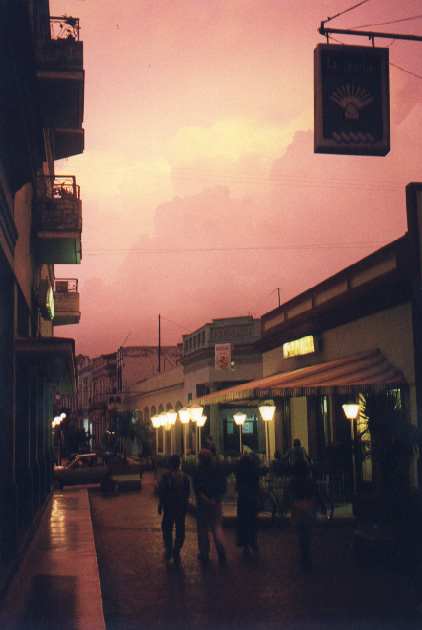

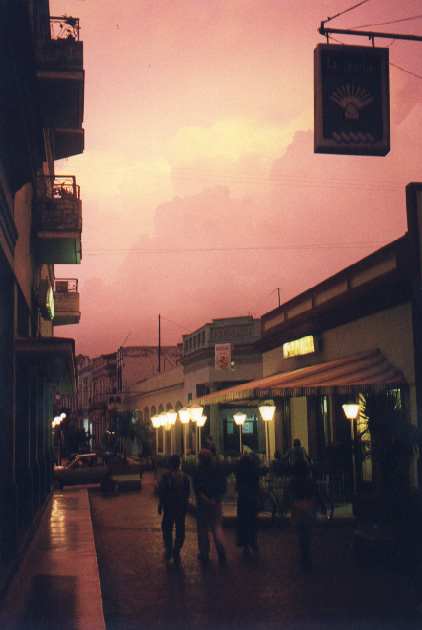

Along the Malecón

[Link to full-size version]

The Malecón itself - by which I mean the buildings ranged along

the waterfront - was an impressive sight. Earlier I mentioned the dereliction

of most of the dwellings in the older part of town. Perhaps surprisingly,

it is nowhere more evident than in the grand mansions lining one of the

really choice strips of riviera in the western hemisphere. The state of

these is frankly shocking. I was warned to walk well away from the overhangs;

a young girl had reportedly been killed by falling masonry. Hundreds of

edifices collapse each year throughout Havana, and it is striking to see

the densely-packed buildings of the Malecón Tradicional abutting

onto lots filled with rubble. How much sounder could the buildings attached

be? But they were still standing, and still well-populated.

The Malecón itself - by which I mean the buildings ranged along

the waterfront - was an impressive sight. Earlier I mentioned the dereliction

of most of the dwellings in the older part of town. Perhaps surprisingly,

it is nowhere more evident than in the grand mansions lining one of the

really choice strips of riviera in the western hemisphere. The state of

these is frankly shocking. I was warned to walk well away from the overhangs;

a young girl had reportedly been killed by falling masonry. Hundreds of

edifices collapse each year throughout Havana, and it is striking to see

the densely-packed buildings of the Malecón Tradicional abutting

onto lots filled with rubble. How much sounder could the buildings attached

be? But they were still standing, and still well-populated.

There are several things to be said in defense of Cuban government policy

here. First, the reason Havana shows such signs of neglect is because the

Castro regime went against the Third World trend of concentrating resources

in the cities, the primate city in particular. Instead, investment in the

countryside greatly increased the social infrastructure there. Together

with state controls over internal movement, peasants were kept from flooding

into Havana by the millions and overwhelming it, the way that dozens of

urban centres in Latin America and around the world have been overwhelmed.

Second, the state did make a meaningful effort to evaluate the

soundness of these old buildings and to take appropriate counter-measures.

Take Alexander, for example - the provider of the libreta statistics.

He used to live right next door to Oscar (there is a hole in Oscar's wall

that actually looks down on the gutted interior of the building next door).

Sometime in the last couple of years, the house was declared uninhabitable.

The state, though, found Alexander and his father alternative housing -

in a modern apartment block at Alamar, across the bay and close to the

beach. Alexander considered it a real improvement: safer, less congested,

and much better for picking up girls. (We were at the height of the Cuban

holiday season, and in the afternoon the streets of Havana were full of

young men and women returning from a day at the fine municipal beaches.

They wandered in their still-damp bathing suits, with the sleepy look of

the sun-stunned.)

Kids on the Malecón

Lastly, one could note that at least the inhabitants of these once-glorious

buildings along the Malecón were ordinary people rather than millionaire

exploiters. There is nothing to separate the inhabitants of one of the

Malecón's mansions from any other residents of Havana - except perhaps

that they are slightly poorer. When the poor live in the houses of the

rich, even if those dwellings have run thoroughly to seed, you know a true

social revolution has taken place.

Lastly, one could note that at least the inhabitants of these once-glorious

buildings along the Malecón were ordinary people rather than millionaire

exploiters. There is nothing to separate the inhabitants of one of the

Malecón's mansions from any other residents of Havana - except perhaps

that they are slightly poorer. When the poor live in the houses of the

rich, even if those dwellings have run thoroughly to seed, you know a true

social revolution has taken place.

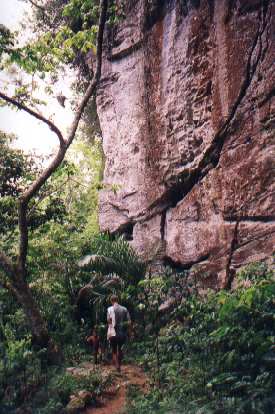

The long strolls through the city have their plot twists. Yesterday

afternoon I returned from a long and sun-soaked concert in the Callejón

de Hamel, where Salvador's striking street-murals were found. The sound

system collapsed in a hail of feedback about half an hour into the set,

but the final band of the day, at least, was able to rise to the occasion.

It was the mostly-female percussion group pictured earlier in these dispatches,

and it chanted and drummed with such mesmerizing intensity that microphones

were superfluous.

Cubans enjoying the music in the Callejón

Hamel

I headed back to the casa particular; and only a block or so from

the gate, in broad daylight, a local lad nearly made away with my shoulder-bag.

The attempted snatch-and-grab was done on foot, rather than on a bicycle,

which may have been to my advantage. I had a reasonably secure hold, and

the bag was too well-constructed to be separated from the strap. Good thing,

too. In the bag was my camera, with nearly a full roll of photos, and also

my Lonely Planet guide.

I headed back to the casa particular; and only a block or so from

the gate, in broad daylight, a local lad nearly made away with my shoulder-bag.

The attempted snatch-and-grab was done on foot, rather than on a bicycle,

which may have been to my advantage. I had a reasonably secure hold, and

the bag was too well-constructed to be separated from the strap. Good thing,

too. In the bag was my camera, with nearly a full roll of photos, and also

my Lonely Planet guide.

After a couple of seconds of this Canada-versus-Cuba matchup in the

Ill-Will Games, my assailant gave up. He released the bag, and took off

at a brisk pace down the street, while I tried to remember the Spanish

for "coward" to yell after him. I walked the extra block to the casa,

heart pumping faster but not racing, shaking my head. I felt glad I'd won

the round, and vowed to wear that damn strap across my chest in the future,

even if it did heighten the discomfort of a soggy T-shirt. There was no

trauma to speak of, obviously. You know from an earlier entry that I was

aware of the bag-snatching danger. Anything without a weapon involved barely

rates as an assault, in my view; and assaults with weapons are unknown

in Cuba. But I was glad to keep the bag and its contents: thanks, Miriam,

for buying me such a tough little item for my travels.

Centro Habana skyline, storm brewing

The biggest problem remains food. It's funny how one's standards and outlook

can change in the space of a single week. My first night in Havana, I was

noting with surprise the amount of street food available for Cuban pesos,

and complaining about the buffet breakfast at the Hotel Capri. A week later,

I am marveling at how gruesomely bland is most of that street fare; and

remembering fondly that breakfast at the Capri ... Waffles! Waffles like

frisbees, yes, but waffles! Omelettes! All the citrus fruit you could eat,

as long as it was grapefruit!

The biggest problem remains food. It's funny how one's standards and outlook

can change in the space of a single week. My first night in Havana, I was

noting with surprise the amount of street food available for Cuban pesos,

and complaining about the buffet breakfast at the Hotel Capri. A week later,

I am marveling at how gruesomely bland is most of that street fare; and

remembering fondly that breakfast at the Capri ... Waffles! Waffles like

frisbees, yes, but waffles! Omelettes! All the citrus fruit you could eat,

as long as it was grapefruit!

The lineup of Cuban street food can be categorized as follows: 1) Pork

sandwiches of the decent type I scoffed on my first night in town; quite

rare, and very expensive in peso terms. 2) Pork sandwiches of a cheaper,

cruder, and altogether more gruesome variety, some of which are merely

white bread and gristle - you never know until you bite. 3) White bread

with butter. 4) Peanuts in paper funnels. 5) "Pizza." This is made from

baking-pan sized loaves of "bread" delivered by the truckload, then sprinkled

with a cheeselike substance (occasionally - very occasionally - with flecks

of onion or ham). This is then baked until thoroughly permeated by grease,

something which could be said for the street food as a whole. One day I

will write a (short) cookbook of such cuisine, called Fried Crap of

Cuba. 6) Refrescos (soft-drinks), of two or three basic types

and limitless in-house variations; some as refreshing as their name, some

like grim medicine. 7) Cheap industrial rum (not that I'm complaining about

the cheap part). 8) Coffee in strong, black shots like espresso, or café

con leche. Both are sweet and quite palatable; but while they may sustain

the traveler's spirit, they have no nutritive content whatsoever. This

is only slightly less than the other foodstuffs possess.

The list basically exhausts the culinary options at street-level in

Havana. A question immediately arises: why does a state-socialist regime

that runs just about every street-stall in the country allow such rubbish

to be served to the masses? The authorities might protest that it was simply

the Cuban taste to dig into such bland and greasy fare. As for me, whatever

enthusiasm I felt for the pre-fab pizza and mulched-pork sandwiches has

dissipated. I am turning into a gastronomic guerrilla, striking whenever

the opportunity permits - which is rarely. To this point, my only really

decent meal in Cuba has come at a paladar (private restaurant) to

which I, a Spanish woman named Alicia, and her Cuban friend Margareta were

led by the trusty Oscar, in the wake of that concert in the callejón.

The paladares have sprung up like mushrooms since state regulation

of private enterprise was eased in 1992-93. They tend to offer better food

and service than the state-run restaurants (which at my price level usually

serve either fried chicken or pork, both dreadful, and french fries like

woodchips). We paid US $7, plus beer, for solid and tasty fare that was

more than we could eat. I've decided I will either have to seek out these

places more determinedly in the future, or make all-inclusive arrangements

at casas particulares. For the time being, it's depressing always

to have a rumbling in your stomach and nothing within half an hour's walk

that really satisfies it - nothing I've yet found, anyway.

Friday, 13 August 1998

Santa Clara, Province of Villa Clara

I have just learned the true meaning of the word "laptop."

I'm sprawled out on my narrow but tolerably comfortable bed in the Hotel

Santa Clara Libre, writing these words on my Samsung portable after a few

hours of sightseeing in my first Cuban city outside Havana. The hotel room

wasn't something I'd anticipated. But when you don't roll into town until

4 a.m. ...

The train to Santa Clara was scheduled for 3:30 in the afternoon. I

got there early to be on the safe side. I needn't have bothered. It wasn't

until six or so that the train for Santiago de Cuba, which stopped in Santa

Clara, finally pulled into the station. It was the first train I'd actually

seen moving in the four hours or so that I'd been lounging. The wait, though,

gave me a chance to strike up a conversation with three friendly Dutch

guys - Paul, Pieter, and Ton. They were headed to Santa Clara as well,

and we continued our chat on the train. The loading was orderly, the carriage

air-conditioned and fairly comfortable, with an eclectic mix of backpackers

and Cubans.

As it transpired, we all had plenty of time to bond. Rumours swirled

of a derailment somewhere along the line, necessitating a detour. Sure

enough, round about midnight - already past our scheduled arrival time

in Santa Clara - Paul checked his map and confirmed the situation: we were

near Matanzas, a third or so of the way to Santa Clara. Well, it was a

chance to catch a few hours' shut-eye, and to have a sweet, faintly erotic

dream about Alona, the exuberant Israeli woman I'd just met, curled up

at that moment on the seat beside me.

When we trundled into Santa Clara at four in the morning, the Dutch

and Canadian contingent - all four of us - determined to benefit from the

new economies of scale. We could actually split double-rooms in a "peso

hotel" on the central square. By "peso hotel," I refer to another hybrid

Cuban institution. Peso hotels serve mainly Cubans, though by the looks

of things the better-heeled. They pay pesos; foreigners - stop me if you've

heard this one before - pay the same in dollars. What's more, there is

no guarantee that a given peso hotel will put you up. The first two we

tried in the bleary pre-dawn hours in Santa Clara told us they were "full."

It was almost certainly a nice way of saying, "We don't take gringos."

Once we'd reconciled ourselves to the Santa Clara Libre, the only hotel

that would have us, we had to sprawl in the lobby until seven, when the

check-in opened for the new day of registration. Perhaps there will come

a day when the $13.50 I would have had to pay for the extra night's rent,

in order to get to the room and to sleep right away, wouldn't seem worth

crashing out for. But by luck, the Santa Clara Libre had a decent lobby,

including a couple of overstuffed chairs. At 7 a.m. we were ushered to

our rooms, which were small, cramped, and bearable - even if the toilet

didn't flush (a bucket was provided), there was only cold water (from the

hot tap), and the water could be - and was - turned off for up to twenty

hours at a stretch.

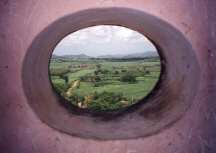

What the Santa Clara Libre has in spades is recent history. The guidebook

informs me that the chipping and scarring on the façade of the hotel

was the result of bullet and artillery fire during the decisive final battle

of the Cuban Revolution, fought in these streets between 12 December 1958

and 1 January 1959. In what was certainly his finest moment as a military

commander, Che Guevara led a column of hundreds of rebels across half of

Cuba, from east to west - from their original redoubt in the mountains

of the Sierra Maestra, to the range of the Sierra del Escambray, which

begins a few kilometers south of Santa Clara. From those peaks, the rebels

launched their assault. Over the course of two weeks, they reduced the

operating range of the Cuban military to the very center of the city. Attempting

to break the siege, the Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista, dispatched an

armoured train filled with over 400 soldiers and heavy weaponry to the

city. An 18-person rebel strike force derailed the train with a bulldozer

- now mounted on a pedestal just down the road and over a bridge from the

central square. Alongside is the wreckage of the train itself, which

has been turned into a revolutionary memorial and museum. After an hour-and-a-half's

fighting, Batista's troops gave up: there wasn't necessarily a lot of reason

for those conscripts to be too enthusiastic about the engagement in the

first place.

The Hotel Santa Clara Libre

The Battle of Santa Clara was the straw that broke Batista's back. It essentially

ended with the seizure of the armoured train on 29 December 1958; by 1

January the dictator was heading out of the country to a comfortable exile

in Franco's Spain. That same day, the last of his forces surrendered in

the Gran Hotel. Well, it turned out the damage to the exterior of the building

I was staying in was more than the result of random shooting in the square.

The Gran Hotel was renamed the Santa Clara Libre after the revolution -

so I had the unexpected pleasure of spending a couple of nights in something

of a historical landmark.

The Battle of Santa Clara was the straw that broke Batista's back. It essentially

ended with the seizure of the armoured train on 29 December 1958; by 1

January the dictator was heading out of the country to a comfortable exile

in Franco's Spain. That same day, the last of his forces surrendered in

the Gran Hotel. Well, it turned out the damage to the exterior of the building

I was staying in was more than the result of random shooting in the square.

The Gran Hotel was renamed the Santa Clara Libre after the revolution -

so I had the unexpected pleasure of spending a couple of nights in something

of a historical landmark.

Che, as commander of the battle that finally brought the revolution

to power, is most closely identified with Santa Clara. In 1997, when his

remains were dug up from the lonely Bolivian landscape in which he'd died

thirty years earlier, they were brought back with great ceremony to Santa

Clara, and reinterred in a huge memorial on the outskirts of town. They

are housed in a crypt, blessedly cool in the August heat; there is an eternal

flame. Buried alongside Che are most of the guerrillas who died beside

him in the Bolivian altiplano - the squalid end of a failed campaign

to spread the revolution beyond Cuba.

Che had travelled the length and breadth of Latin America before taking

up arms alongside Fidel Castro in 1956. Of all the countries he'd seen

en route, Bolivia seemed to him the most desperately poor and ready to

explode in revolution. Bad guess. There'd already been a revolution

in Bolivia in the 1950's. One of those half-revolutions, more like

it; but enough to entrench a notion that change was possible within

the system. The enormous difficulty of overcoming this skepticism, and

the cultural gulf between his tiny rebel force and the Aymara Indians of

the highlands, Che described with candour in the Bolivian Diary

published after his death. There was also the United States to be reckoned

with - well on its way to losing its first war at the time, and terrified

of Che's promised "one, two, many Vietnams." The U.S. flew in the Green

Berets to guide the Bolivian search forces, and added their unmatched surveillance

capabilities to the quest. It was enough to bottle Che up, capture him,

and execute him and his comrades in the presence of the U.S. advisors.

But over thirty years later, a fiasco like the Bolivian campaign tends

to recede into the background. It is as an icon that Che lives today -

and nowhere more than in Santa Clara, where every third resident seemed

to be wearing a T-shirt adorned with his brooding features.

The cynic might argue that from Fidel Castro's perspective, Che could

be safely lionized because he was safely dead. The two had had their disagreements

- resulting in Che's abandoning his ministerial post in the revolutionary

government and taking once again, this time disastrously, to the field.

Castro has exhibited moments of paranoia and/or calculated brutality towards

revolutionaries whom he views as rivals - as with the execution of General

Arnoldo Ochoa in 1989. So it is not impossible that the relations between

Fidel and Che are closer in death than they would have been in life.

This, though, would reckon without the genuine bond established between

the men who carried Cuba to the brink of revolution and beyond: to the

radical re-creation of Cuban society that took place in the first half

of the 1960s. In his farewell letter in 1966, Che wrote that if he, an

Argentine, died under foreign skies, it would be with the thought of the

Cuban people in his mind, "and above all you" - that is, Fidel. Che now

incarnates the heroic phase of the Cuban revolution, which Castro has exploited

to buttress his rule ever since. Forty years on, the story of the

Cuban Revolution has become less heroic. Or has it? It still seems bizarre

- delightful, somehow - that this impudent Third World revolutionary experiment

could survive only a few miles from the Florida Keys. That Castro himself

could have listened to the proclamations of his impending downfall issued

by one U.S. president after another ... and another ... and another. (Eight

in all, and counting.) It seems preposterous that any country could

have survived a 70-percent fall in production (1989-1994) without the regime

being violently overthrown. In Cuba, would-be emigrants crowded into dilapidated

boats and onto wooden rafts, and braved the shark-infested route to Florida.

But there were no riots in the streets, at a time when state-socialist

regimes worldwide were falling like ninepins.

Regime repression explains this only partly. An equally powerful factor,

manipulated and still in some sense incarnated by Castro and his regime,

is nationalism. I have been hearing a great deal over previous days - in

Havana, on the train to Santa Clara, and now in the streets of the city

- about life in Cuba. Much of it has been scathingly critical. But I have

also encountered a quiet, impressive pride in being Cuban - not the trigger-happy,

chip-on-the-shoulder, poverty-induced psychosis of certain other Caribbean

islands (Jamaica and Haiti come to mind). Some of it may just be that indefinable

"national spirit," but a great deal, it seems to me, has to do with what's

happened in Cuba since 1959.

The most eloquent testimony on this count was Oscar's, delivered the

night before I left Havana. "Do you know what separates this country from

many others?" he asked rhetorically. "Education. When you are educated

you can take your destiny in your own hands." Both he and Alexander were

fairly sanguine about Cuba's near-term prospects. This was a strong people,

said Oscar. It had endured a lot. The "Special Period" of the early '90s

was brutal, but there'd been some improvements since. Slight, but measurable.

"You see it yourself, my friend. People are surviving."

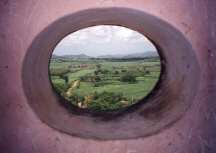

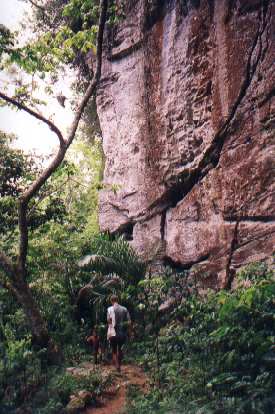

Direnia, Yaima, Migdalia:

Train to Santa Clara

[Link to full-size image]

On the train to Santa Clara I met Migdalia: a forceful working-class woman,

mid-thirties at a guess, who toiled in the tobacco fields of Havana province.

She described enthusiastically and in detail the variety of tasks she performed

- inspecting the leaves for insects or fungus, harvesting them, hanging

them to dry in the shed, and so on. She talked about the house she held

title to. She'd bought it for 1,200 pesos - a year's wages. You'd have

to be pretty far up the economic scale before you could make a proportionate

purchase in Canada. (And you'd be paying more than seventy dollars for

a house.) Meanwhile, Migdalia's utterly radiant kid, Yaima, was joining

an equally irresistible playfriend, Direnia, in clambering all over the

smattering of foreigners in the railway car. Both Yaima and Direnia already

spoke a clear, educated-sounding Spanish; neither of them wanted more from

us than good-humoured attention; and every time they smiled, their white,

white teeth beamed like beacons. They were the children of the "Special

Period," as their mother was a daughter of the revolution's heroic years.

But Castro had vowed not to close a single hospital or daycare center during

the years of austerity, and to keep the milk coming. Even during the gruesome

economic crisis of the early '90s, evidence indicated the promise had been

kept.

On the train to Santa Clara I met Migdalia: a forceful working-class woman,

mid-thirties at a guess, who toiled in the tobacco fields of Havana province.

She described enthusiastically and in detail the variety of tasks she performed

- inspecting the leaves for insects or fungus, harvesting them, hanging

them to dry in the shed, and so on. She talked about the house she held

title to. She'd bought it for 1,200 pesos - a year's wages. You'd have

to be pretty far up the economic scale before you could make a proportionate

purchase in Canada. (And you'd be paying more than seventy dollars for

a house.) Meanwhile, Migdalia's utterly radiant kid, Yaima, was joining

an equally irresistible playfriend, Direnia, in clambering all over the

smattering of foreigners in the railway car. Both Yaima and Direnia already

spoke a clear, educated-sounding Spanish; neither of them wanted more from

us than good-humoured attention; and every time they smiled, their white,