• The change-desk at the Hotel Nacional in Havana had only one-dollar bills, and no idea how long the drought of higher denominations would last. So I packed three hundred one-dollar notes for my travels to the interior, and have been gradually eroding the stacks since. It lends greater substance to the money, somehow. A little closer to the weight it carries for the Cubans, who count every dollar bill with some reverence: recall Carmen's standing fan.

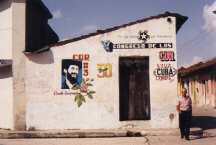

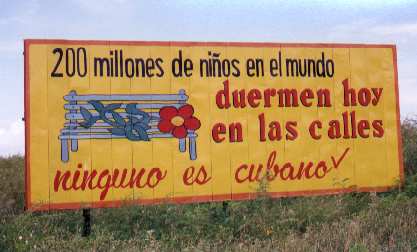

• Surprise at the restraint shown in the visual propaganda. I'd expected billboards every second block, walls emblazoned. But they've been more sporadic presences, both in Havana and destinations since. I saw my first portrait of Fidel Castro on a billboard two-and-a-half weeks into the trip. Dozens of images of Che; virtually none of Fidel. As a personality cult - five-hour speeches notwithstanding - Castro's seems of a far different order than, say, Asad's in Syria, where portraits of the maximum leader hang as shrines in living rooms. (The wittiest propaganda I've seen so far: a T-shirt reading, "Sin embargo, Cuba." "Sin embargo" in Spanish means "however"; here, it has connotations of exceptionality, of survival. Read another way, though, the phrase means, "Without embargo" - i.e., a call to end the U.S. sanctions.)

• Disturbing glimpses of the racism that still exists in Cuba, despite a substantial degree of success after the revolution in empowering Blacks educationally, economically, and to some extent politically. That melancholy 100-peso-a-month pensioner in Santa Clara had casually slipped the word "niggers" into his halting English speech. When I protested, he countered that he had nothing against Black people, especially women; in fact, he'd "had" that Black girl at the pharmacy down the road - no more than 30 years old! Except he didn't say "had." In Trinidad, a driver and mechanic, about as old as the revolution, told me absolutely flatly that Black people could not be trusted; that they were responsible for the vast majority of crime in Cuba - "Check the statistics, man." He was adamant that behaviour really followed from skin pigmentation, and squeezed the flesh of his forearm to emphasize the point. "White people have the initiative and desire to make things better for themselves. Black people don't want to do any work. They just want to sit around and bang on drums all day." "So you're White?" I asked in some wonderment: in North America, he would have been counted among darker-complexioned Latinos. "Of course!" he answered, evidently never having contemplated otherwise.(1) I tried to point out that in Florida or Los Angeles, Latinos - Cubans specifically - were likewise stigmatized as untrustworthy, lazy, criminal. I didn't get very far, although he was tolerant enough of my unorthodox perspectives.

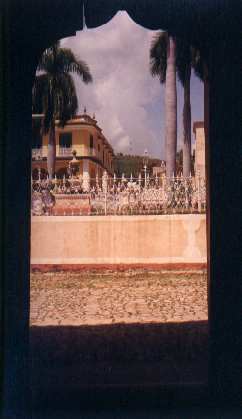

Trinidad backstreets

[Link to full-size

image.]

Everywhere

in Cuba I find it important to stop awhile on a street corner to watch

life pass by. Cheap rum stalls are conveniently provided, and are fine

places to chat up at least one of the sexes in Cuba. In Trinidad, a day

or two after the conversation described above, I found myself knocking

back an aperitif with three agreeable gentlemen, all of whom happened to

be Black. How far did the racist sentiments expressed to me in private

translate at street level? I put the question bluntly to the company, and

was surprised to get in return the most adamantly pro-revolutionary sentiments

I'd yet encountered in Cuba. One of my fellow drinkers was a basketball

coach; another a factory worker; another a technician with the water authority.

All stressed that they had never felt the remotest impediment to rising

as high as their talents would take them. Nor did they feel any hostility

or derision in the workplace. "The revolution changed all that," said one

of the men, an older guy who remembered pre-'59 vividly. "As long as you

have education, you can go far in this country." For him it was "Socialism

or death." (In Camagüey, a couple of stops down the road, I would

put the same question to two Black guys in the street. Yes, both agreed,

there was racism in Cuba; but not of a kind that manifested itself

in the workplace or in dealings with the bureaucracy. When, then, did it

rear its ugly head? "For example," said one of my informants, "if I were

walking the street with her" - and here he grabbed the wrist of Katherina,

the attractive German woman I happened to be strolling with, holding on

longer than was strictly necessary. "People would talk behind your back.")

Everywhere

in Cuba I find it important to stop awhile on a street corner to watch

life pass by. Cheap rum stalls are conveniently provided, and are fine

places to chat up at least one of the sexes in Cuba. In Trinidad, a day

or two after the conversation described above, I found myself knocking

back an aperitif with three agreeable gentlemen, all of whom happened to

be Black. How far did the racist sentiments expressed to me in private

translate at street level? I put the question bluntly to the company, and

was surprised to get in return the most adamantly pro-revolutionary sentiments

I'd yet encountered in Cuba. One of my fellow drinkers was a basketball

coach; another a factory worker; another a technician with the water authority.

All stressed that they had never felt the remotest impediment to rising

as high as their talents would take them. Nor did they feel any hostility

or derision in the workplace. "The revolution changed all that," said one

of the men, an older guy who remembered pre-'59 vividly. "As long as you

have education, you can go far in this country." For him it was "Socialism

or death." (In Camagüey, a couple of stops down the road, I would

put the same question to two Black guys in the street. Yes, both agreed,

there was racism in Cuba; but not of a kind that manifested itself

in the workplace or in dealings with the bureaucracy. When, then, did it

rear its ugly head? "For example," said one of my informants, "if I were

walking the street with her" - and here he grabbed the wrist of Katherina,

the attractive German woman I happened to be strolling with, holding on

longer than was strictly necessary. "People would talk behind your back.")

• Glimpses, too, of the machismo that the revolution hardly stamped out - but with variations. In Havana, it was brazen and public. To stroll the streets with César, for example, was to hear him deliver a veritable symphony of hisses and wet kisses to every young, conventionally attractive female within a block's range. On numerous occasions I watched a woman walk along a city street and be literally deluged with such attentions. As best I could gauge, the women weren't giving anything back; that is, they weren't obviously playing along with "the game."

On the Callejón Hamel, Havana

[Link to full-size image.]

I had dinner one night with Mercedes, a Californian woman who was determined

to spend some months in Cuba - she was seeking work as a translator or

newsreader on one of the radio stations. But she had nearly turned tail

and split when she first encountered the whistles and hisses downtown.

She had, though, made her peace with it, to some extent at least. "At least

they're not ... I don't know ... timid about it."

I had dinner one night with Mercedes, a Californian woman who was determined

to spend some months in Cuba - she was seeking work as a translator or

newsreader on one of the radio stations. But she had nearly turned tail

and split when she first encountered the whistles and hisses downtown.

She had, though, made her peace with it, to some extent at least. "At least

they're not ... I don't know ... timid about it."

The difference in atmosphere in the smaller towns I've visited since Havana has been striking. Only rarely in Santa Clara, or Remedios, or Trinidad, have I seen a woman subjected to the full-bore treatment. Things seem lower-key and more respectful away from the metropolis. What's happening beneath the surface is another matter, of course. I chatted with a jinetera, one of the women hoping to attach herself to a wealthy foreigner, on the beach at Playa Boca outside Trinidad. She had a three-year-old son, and no husband to be seen. "That's how it is for ninety percent of the women with kids."

• Incomprehension at some of the production decisions made here - the vast majority of them, of course, by the state. It is possible to find Cuban-made shampoo and other toiletries on sale, for dollars, in the supermarkets. But it is striking the number of items that are simply imported and sold for dollars - goods which could easily be undersold by acceptable Cuban product, and used to generate jobs and small industry. The supermarkets sell Nabisco crackers, a small packet, for $1.50 or so; how hard is it to make crackers, if you're already baking bread? Why doesn't this product cost 25 cents, as it would in any other Latin American country? There are cigar-cutters, brand-name Cubano, on sale at the Casa del Tabaco in Trinidad. At about a dollar each, it's a very fair price; but they're imported from Italy. The packaged mystery meat, as noted, comes from Canada. Why is import-substitution not being practised? Is it simply that the state's profit margin is larger when it marks up the imports and rakes in the proceeds from those lucky enough to hold dollars?

• The fanaticism with which afternoon soap operas are watched. To walk the streets of a town when the Colombian telenovela is on, between 3 and 5 p.m., is to encounter an eerie calm, broken by melodramatic tones of conspiracy, betrayal, and the final victory of good over evil. "When Babú gives a speech, he goes on and on," says one informant, using the familiar corruption of El Barbo, "The Beard," to refer to Fidel Castro. "You see people checking their watches, and getting nervous when he runs over into the time-slot for the telenovela." Watching Cubans watch the novelas doesn't have quite the cultural dissonance of seeing conservative Muslims (and the Canadian backpacker) hooked by the scheming and cleavage of The Bold and the Beautiful - a fond memory of Amman. But it's close.

• The mystique attached to "everyday" consumer items here. One morning in Trinidad, I decided to give my linen shirt a good ironing with the Black & Decker travel iron I'd brought on the trip. It had attracted some mockery from friends in Canada, who figured I was turning bourgeois; but when I brought it out to the kitchen table at Norma and Umberto's, it was though I'd performed an intricate magic trick. "¡Que maravilla!" (How marvellous!) exclaimed Norma, and a casual (male) visitor also seemed awestruck by the display. "Cubans don't iron their clothes," said Norma. Well, on special occasions, perhaps - Norma would go down the block to use the old one her mother had. This, she assured me, was standard practice.

View over Trinidad

from the Casa Cantero

[Link to full-size

image.]

In

the afternoon, I headed over to the Municipal Historical Museum. It was

housed in the Casa Cantero, formerly the home of a renowned 19th-century

sugar baron. (He owned the Manaca Iznaga, the fields surveyed through the

window of the slavetower in the

Valle de Ingenios.) The museum's exhibits traced the development of Trinidad

over the centuries. Accompanying the Spanish commentary was an English

translation obviously prepared by a specialist - in Russian: "The Spain

colonisation, carried out the aborigine destruction by means of an inhuman

regimen of exploitation though charge." "As result of sugar downfall in

Haití, by the ends of XVIIIth century the trinitarians

[i.e., residents of Trinidad] found a reception in sugar bowl industry,

such as the third part of available lands of Dan Luis Valley had taken

before the second colonizar process."

In

the afternoon, I headed over to the Municipal Historical Museum. It was

housed in the Casa Cantero, formerly the home of a renowned 19th-century

sugar baron. (He owned the Manaca Iznaga, the fields surveyed through the

window of the slavetower in the

Valle de Ingenios.) The museum's exhibits traced the development of Trinidad

over the centuries. Accompanying the Spanish commentary was an English

translation obviously prepared by a specialist - in Russian: "The Spain

colonisation, carried out the aborigine destruction by means of an inhuman

regimen of exploitation though charge." "As result of sugar downfall in

Haití, by the ends of XVIIIth century the trinitarians

[i.e., residents of Trinidad] found a reception in sugar bowl industry,

such as the third part of available lands of Dan Luis Valley had taken

before the second colonizar process."

Trinidad portico

Slightly

befuddled by this, I took one final wander through Trinidad's streets,

bathed in the robust orange hues of a Caribbean late afternoon. A cheerful

woman called to me from her doorway, inviting me to take a look at the

casa particular she runs. She was a week too late, and I was glad to have

ended up with Norma and Umberto; but I took the opportunity to chat with

her, and pick up an address for a casa that one of her relatives

ran in Camagüey. (Thus are the casas particulares publicized

informally, and advance arrangements made. An American woman named Allison

will also supply independent travelers with a list of casas throughout

Cuba, with up-to-date prices and traveler's comments: allisonaa@geocities.com.)

Two young backpackers were smoking Cohibas - fake ones, they figured -

in the living room. Scott and Alex: both from California. I sounded them

out on their Cuba travels. Like many American visitors, they'd chosen to

ignore the U.S. government ban on travel to Cuba, rather than submit themselves

to the lengthy and complicated licensing procedure that the government

requires for "legitimate" travel to the island. They'd come down through

Mexico and, like me, hopped over from Cancún. Two weeks down, and

they had one left to go. Their verdict? "It seems to me the image that

both governments have of each other is really extreme," said Scott. "It's

good to come here and see things as they are." Though every inch the tanned

surfer type, he was far from a slacker: he spoke excellent colloquial Spanish,

thanks to a degree program in Spanish literature and a year spent in Barcelona.

"I love how mellow you Canadians are about Cuba," he told me. "The policy

we've got now is the work of a bunch of old people in Congress. They're

living in the past."

Slightly

befuddled by this, I took one final wander through Trinidad's streets,

bathed in the robust orange hues of a Caribbean late afternoon. A cheerful

woman called to me from her doorway, inviting me to take a look at the

casa particular she runs. She was a week too late, and I was glad to have

ended up with Norma and Umberto; but I took the opportunity to chat with

her, and pick up an address for a casa that one of her relatives

ran in Camagüey. (Thus are the casas particulares publicized

informally, and advance arrangements made. An American woman named Allison

will also supply independent travelers with a list of casas throughout

Cuba, with up-to-date prices and traveler's comments: allisonaa@geocities.com.)

Two young backpackers were smoking Cohibas - fake ones, they figured -

in the living room. Scott and Alex: both from California. I sounded them

out on their Cuba travels. Like many American visitors, they'd chosen to

ignore the U.S. government ban on travel to Cuba, rather than submit themselves

to the lengthy and complicated licensing procedure that the government

requires for "legitimate" travel to the island. They'd come down through

Mexico and, like me, hopped over from Cancún. Two weeks down, and

they had one left to go. Their verdict? "It seems to me the image that

both governments have of each other is really extreme," said Scott. "It's

good to come here and see things as they are." Though every inch the tanned

surfer type, he was far from a slacker: he spoke excellent colloquial Spanish,

thanks to a degree program in Spanish literature and a year spent in Barcelona.

"I love how mellow you Canadians are about Cuba," he told me. "The policy

we've got now is the work of a bunch of old people in Congress. They're

living in the past."

The evening, my last at Norma and Umberto's, was given over to the event I'd been dreading: my advance birthday party. Mercifully, it proved to be a pleasant, rather low-key affair. Umberto had sunk cash into a whacking great thigh of pork, seasoned and smoked with a carapace of crisp, crackling skin. There was a cake, but not an overly-extravagant one. A freezer-full of creamy Mayabe beer was my own contribution. We gorged and talked late into the evening, and I uncovered further details that made my fantasy of returning and setting up a property here seem a little less idle. According to Umberto, a decent house could be had in Trinidad for around $1,000; the second storey he was planning to build on his own dwelling would run him around $600. A fishing boat cost in the same neighbourhood. Orlando, the wiry old grandad of the clan, offered with a gleam in his eye to take care of anything I might choose to buy, register in his name, and moor nearby.

At about 11 o'clock, woozy from the pork and beer, I said my goodbyes and headed - briefly - to bed. The bus for Sancti Spíritus, a two-hour ride, was scheduled to leave at 3:30 a.m. (who dreams up these schedules?). Norma and Umberto had kindly agreed to let me crash for the truncated night free of charge. I drifted off into a light sleep almost as soon as my head hit the pillow.

Towards 3 a.m., I roused myself, pulled on clothes, and lugged my bags through the near-silent streets of Trinidad to the bus station. There, as a dollar-paying foreigner, I was ushered into a separate waiting room. I sat smoking the stale tail end of a stogie and listening to a guitarist in the adjacent hall, softly strumming to pass the time. There was not much reason to feel happy, turfed out of bed at an ungodly hour and biding my time alone in a dingy little salon. But I felt oddly exhilarated. The next (and closing) few days of my journey would take me still further east, away from Havana and my flight back to Guadalajara. But soon I would close the loop of my Cuban travels, and of four months away from home and loved ones. Meanwhile I was on the move, with new places and experiences ahead. No traveler could ask for more.

The hush of the predawn hours was broken when our bus lumbered into view. It was like something out of a Japanese sci-fi movie: a big, boxy carriage pulled by a semi-trailer cab. I was seated first. Then the crowd rushed through the turnstiles, laughing and chattering. Very quickly it was standing-room only, though the carriage was not desperately congested. The bus groaned and squeaked its way out of Trinidad and onto the deserted main highway to Sancti Spíritus. Out the window the night sky exploded with stars; distant flashes of lightning lit up the horizon.

We rumbled into Sancti Spíritus around a quarter past six, dawn just breaking. Blearily I climbed aboard one of the horse-drawn carriages parked across the street, and paid a peso for the gentle two-kilometre trot to the centre of town. A bed, a bed, my kingdom for a bed ... but the first place I tried was chock-full. It was run by Ricardo, a genial sixty-year-old man known far and wide as El Taxista for his former occupation (cab-driver, not tax-collector). Ricardo had set up his rooming-house in the expansive old colonial mansion his family had long owned on the edge of Serafín Sánchez, the central park. It was barely 7 a.m., and there was no room at the inn - Ricardo had been inundated with travelers ever since he managed to get himself listed top in the Lonely Planet guide. But his hospitality was exceptional nonetheless. He dispatched an assistant (or freelance tout) to scour the streets nearby for a casa particular able to take me. Meanwhile he brought me a small plate of bananas and a tall glass of cold, sweet, delicious ... milk! "How do you manage to get hold of this? I thought all the milk was reserved for kids under seven, and nursing mothers." Ricardo smiled, and explained the workings of the bolsa negra - the black market - in Cuba. It was, I learned, one of the key ways in which workers in state enterprises were able to supplement their meagre peso earnings: by filching from the workplace and retailing on the side. If you worked in a milk plant, you took milk. If you worked in a cigar factory, you took cigars - or alternatively, the seals, boxes, and certification labels, which you could then attach to inferior product and sell to unsuspecting tourists. The examples could be multiplied. If you worked in a slaughterhouse, you pilfered meat. If you worked in a brewery, you siphoned off product from the bottom of the vat - which explained those bottles of rougher no-name brew I'd sampled on the Callejón Hamel in Havana. If you had access to a state-owned vehicle, you ran a taxi service in your spare time. The practice was so pervasive that the state seemed to make no serious attempt to interfere with it. Only this way, it appeared, could the socialist fiction of "to each according to his need" be maintained, while pent-up consumer demands were partly satisfied and subsistence wages marginally enhanced.

After a while, Ricardo's friend returned with the news that a casa had a room free down on the Plazelita Hanoi (it was so named in August 1972, at the height of the Vietnam War). The tout led me down a couple of side streets and knocked on a door. It was opened by Gustavo, an elderly, distracted-seeming gentleman; and here my strange euphoria of the last few hours began to dissipate. Compared to Ricardo, Gustavo - "Bebo" to his friends - was a taciturn man: perhaps the first I'd met in Cuba. The price of the room was fifteen dollars. Perhaps my fatigue was obvious enough that he felt no particular need to bargain. He'd read me right. I handed over the cash, along with my passport for the registration process. Gustavo promptly disappeared from view; he would be nearly invisible for the remainder of my stay.

The room was tidy and comfortable enough, but as I lay down in the desperate hope of an hour or two's sleep, I realized the disadvantages of the location. My windows opened onto a street corner that was now filled with early-morning traffic: the magnified mosquito whine of Soviet-made motorbikes, the heavy rumble of trucks, the percussive clip-clop of horses' hooves. I drifted off for a few minutes, but even through my foam earplugs, the cacophony penetrated and kept me from real slumber. In the end I gave up, showered, and thumbed through the editions of Granma lying on Gustavo's coffee table. There was a little - a very little - world news, which only reminded me how completely out of touch I was in Cuba. In the wake of terrorist bombings of its embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, I learned, the U.S. had engaged in another of its semi-annual missile attacks on hapless Third World countries, this time Afghanistan and Sudan. Much more than that Granma wasn't interested in telling me, although there was a lot of stultifying "news" about production quotas. I began to salivate at the prospect of accumulated back-issues of The Economist waiting for me in Vancouver ...

Finally I headed out to the streets of Sancti Spíritus for a look around. The town I'd expected to be a quiet sister of Trinidad was instead in an uproar. Disco music was blasting at full volume in the central square, and more mid-morning revelry was underway on the Avenida de los Mártires. The throngs extended all the way up to the Carretera Central. Banners were hung announcing the 38th anniversary of the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC). Granma, indeed, had informed me that this year Sancti Spíritus was designated host of the celebrations. It was as good an excuse as any for a Saturday street-party, a break in the grinding tedium and austerity of Cuban life. Apart from the banners, there wasn't much to remind the throng of the ostensible reason for the festivities (no speeches, for example). There were, however, plenty of Cuban Women around, Federated or not; a disproportionate number struck me as devastatingly attractive. Something in the local water supply? It was, at least, welcome distraction from the headache I was getting from the music and the crushing heat.

There were logistics to deal with. I planned to continue on to Camagüey by train, but Sancti Spíritus was awkwardly located - about fifteen kilometres off the main east-west rail line. According to Ricardo, to get a train ticket I would have to travel to Guayo, the nearest town on the main line, and hope to secure one of the four tickets reserved for people who board the train at that junction. That meant either an expensive return trip to Guayo by private car, or an early-morning, one-way journey to the same destination, where I could sit around all day waiting for the night-train - if I was lucky enough to get a ticket. It all seemed more trouble than it was worth. I trotted back, sopping with sweat, to the bus station, where I was told that my dollars would have no difficulty getting me a ticket: once again, I needed only turn up an hour before departure to buy the ticket. That was at 6 a.m.

I knocked back street-food - a sandwich that actually had paper-thin slices of cucumber in it; a grease-dripping pizza; a bottle of rough-hewn bootleg beer - and began to feel better. I undertook to reconnoitre the quiet colonial backstreets of Sancti Spíritus, the oldest city founded away from the coast in Cuba. But those streets seemed a little bland after the glories of Trinidad. And disco music aside, there wasn't much else to do or see. When the morning festivities died down, the town grew somnolent, the streets deserted except for the knots of customers milling around the refresco stands. I made my way to the town's main attraction - the Yayabo bridge, built across the river of the same name in the early 19th century. It was a bridge, all right. Back in the Parque Serafin Sánchez, I sat in the shade, smoking cheap sweet cigars; then I strolled back to Bebo's casa, and spent the rest of the afternoon catching up on sleep. It seemed to be the activity (or rather the inactivity) of choice in Sancti Spíritus. I was already glad I'd decided to clear out the next morning.

With the sun setting, I tracked down a paladar near Bebo's house, and settled in for a solid meal on the rooftop. An Italian guy ambled up. He was staying at one of the rooms rented in the same establishment, and we chatted for a while. He was rather impressively ugly, with a squat physique and a kind of permanent sneer set under brooding, bushy eyebrows. For him, not surprisingly, Cuba was a dream come true. He'd been here four times in the past eighteen months. He had his "courtship" ritual down pat: he packed a suitcase full of the women's clothes and shoes that are so hard to obtain in Cuba, and found no lack of novias (girlfriends) willing to take him on in exchange for such goodies and for nights out on the town. After four trips, though, he was beginning to feel jaded. Maybe it was just his latest girlfriend - a lithe, dark-haired creature who glided past us in the middle of the conversation and headed to the room without a word to either of us. She'd spied the Italian talking with another woman in a discothèque, apparently. Now she was "jealous" and giving him the cold shoulder. Maybe it was time for him to get away from all the hassles: he was thinking of spending his next vacation on the other side of the world, in Madagascar ...

I finished my meal and headed back to the park. There I found good-hearted Ricardo - he of the early-morning welcome and the tall glass of milk - taking the evening air. We spoke about the time he'd spent studying in the Soviet Union in 1962 - right through the Cuban missile crisis in October of that year. Hard to believe that this laid-back country could ever have played a role in bringing the world as close as it has come to a nuclear holocaust. Thirty-six years later, here we were still - with Cuba the continuing object of U.S. enmity and sabre-rattling.

I turned in early, around 10 p.m., to get something approaching a night's sleep. The alarm was set for 4:30. That would give me plenty of time to get to the bus station by six and buy my onward ticket for Camagüey. But even after three months on the road, I hadn't figured out the complexities of the infuriating little Radio Shack clock I'd bought for the trip. In the end, it was only my internal alarm that woke me - at 5:38 a.m. precisely. "Shit!" Should I spend another day in Sancti Spíritus? The prospect seemed enervating. The alternative was a manic flurry of activity, possibly the first Sancti Spíritus had ever experienced. I took the briefest of showers, rinsed my contact lenses, dressed, packed, and charged out into the dark streets of the town for the two-kilometre hike to the bus station. Somehow I managed to make it to the ticket window by 6:15: it seemed a bending of the laws of physics to give Stephen Hawking pause.

At the station, everybody was a good deal calmer and more relaxed than the wild-eyed, perspiring Canadian. Fifteen minutes late was irrelevant; my hard currency immediately secured me a seat. The bus was a comfortable contraption with reclining seats; it left at seven on the dot. It seemed a further symbol of improvement in the public-transport situation in the last couple of years. My guidebook, published early in 1997, warned me that since the onset of the período especial, "long-distance bus services around Cuba have been slashed and getting a ticket on one of the remaining routes has become very difficult. ... Tickets for intercity buses have to be purchased at the office in advance, and reservations must be reconfirmed at the terminal about two hours prior to departure." A horror-story from a 1996 trip, posted to the Lonely Planet website,(2) had also filled me with foreboding:

I just came back from my Christmas holidays which I "tried" to spend in Cuba. I write "tried" because, unfortunately, I did not succeed and went away after only three days. ... There is too much talk about how beautiful Cuba's beaches are and about how clear and blue the sea is. What nobody tells you about Cuba is that it is a difficult country to cope with if you decide not to travel in a tour group. ... The point is that there is no way to get around in Cuba. No buses, no trains, a limited number of cars for rent, no way to take a taxi, and the aeroplanes do not fly if there is a shower. To cut a long story short, me and my mate were stuck in Havana for several days with no possibility of moving on from there. The Cuban Tourist Office tried to help us, but there was nothing they could really do because they do not have anything. All hire cars in Havana were booked for days in advance; taxis asked $200 for a trip to Trinidad ...None of this was true in mid-1998, even at the height of internal holiday travel. "Apparently," writes Allison in her impressive and up-to-date Cuba Budget Guide on the 'Net, "one of the first uses Cuba has made of its dollar profits from increased tourism was to band-aid its transportation system, which doesn't suffer nearly the delays and cancellations it did only a year ago."(3) To what extent these improvements have filtered through to non-dollar-paying Cubans is another question. I had heard that Cubans wishing to travel from point to point in their own country had to queue, sometimes for days, for a ticket on a bus or train. Still, there were only two other foreigners on the Camagüey-bound service; the Cuban passengers all had the same reserved and reclining seats as we did, and they benefitted from the same prompt departure time and an arrival actually an hour earlier than the guidebook suggested. It could have been worse, and in recent years it certainly has been.

The

third-largest city in Cuba had a friendly, small-town feel, and a layout

that made it perfect for my favourite activity: getting lost. Following

a couple of destructive pirate attacks, the growing town "was deliberately

laid out in a confusing, irregular way in the hope that assailants would

become disoriented" (LP). It was the sort of place where you could

strike out due east from the railway station, stroll for a couple of kilometres

convinced that you're heading towards the sticks, and then find yourself

right back where you started.

The

third-largest city in Cuba had a friendly, small-town feel, and a layout

that made it perfect for my favourite activity: getting lost. Following

a couple of destructive pirate attacks, the growing town "was deliberately

laid out in a confusing, irregular way in the hope that assailants would

become disoriented" (LP). It was the sort of place where you could

strike out due east from the railway station, stroll for a couple of kilometres

convinced that you're heading towards the sticks, and then find yourself

right back where you started.

In the middle of the flat central plains of Cuba - the heart of the country's cattle industry, home also to verdant rice paddies and fields of sugar cane - Camagüey got little relief from the August heat. I wandered its winding streets until I was drenched and exhausted, then headed back to the air-conditioned room I'd found in the casa particular recommended to me in Trinidad. The proprietor was Alfonso - a little older than myself, with fine aquiline features. He'd opened bidding on the room at $20 a night. By this time, though, I was sufficiently experienced in Cuban ways to know this was exorbitant. I quickly whittled him down to $20 including breakfast and dinner. The breakfasts were comparatively mediocre affairs, but those cenas were the best meals I'd eaten in Cuba: huge spreads of avocado, cucumber, fried banana, rice, and cucumber, all built around choice cuts of pork or lamb. Topping it all off was a very nice touch: a bottle of cold local brew, provided gratis though it had to be purchased in hard currency. And there was always enough strong, sweet café cubano to set my heart palpitating for the rest of the evening.

There were plenty of old colonial churches and monuments in Camagüey, but by this point in my journey I had even less interest in the designated "sights" than was normal for me. I roamed, spotting after the first day or two familiar faces among the strangers who passed in the streets. It was that kind of place.

One of the faces was familiar to me from my previous stop. It belonged to a young German woman whom I'd noticed chatting with a Cuban guy in the park in Sancti Spíritus. We hadn't spoken then, but when I brushed past her in one of Camagüey's winding streets, I stopped and asked her name; we would spend a few hours in philosophical conversation over the ensuing couple of days, most of it passed in the quiet park down the road from my casa, where there was shade and cold beer from the corner-store nearby. Katherina was one of those stalwart young women who'd decided to take on Cuba alone. She had learned, to her pleasure, that traveling here didn't require so much courage after all. Even the wolf-whistles and macho solicitations had ceased to bother her much. "Really, I think for the most part it's just their way of trying to be nice." Her experiences weren't far different from the other solo women travelers I'd spoken with in Cuba and across Latin America. For every unwanted approach, it seemed there was a special assistance rendered, or access granted that a lone male might not have received. I imagine things will only get better as more women discount the nightmare scenarios and set out to see the world on their own.

Small

world. Walking down Camagüey's Avenida República late one morning,

I heard the usual hissing, behind me and across the street: the shouted

"My friend! My friend!" A pedicab driver or tout, I presumed. I studiously

ignored it. Then I was accosted from behind, a hand on my elbow. Now, this

was going too far ... But then the voice asked plaintively, "Don't you

remember me from the train?"

Small

world. Walking down Camagüey's Avenida República late one morning,

I heard the usual hissing, behind me and across the street: the shouted

"My friend! My friend!" A pedicab driver or tout, I presumed. I studiously

ignored it. Then I was accosted from behind, a hand on my elbow. Now, this

was going too far ... But then the voice asked plaintively, "Don't you

remember me from the train?"

That was a new one. I turned - and there was Miguel, the youngish, powerfully-built man who'd whiled away an hour or so with me on the journey to Santa Clara two weeks before. I laughed and embraced him, apologizing. I'd had no idea he lived in Camagüey - but now he invited me to stop by his house for a visit. I promised to do so.

On my last evening in town I set out to fulfill the pledge. Katherina was outbound on the train to Santiago de Cuba late that night. To pass the time, she joined me for the trek to the suburban neighbourhood where Miguel lived. It was a rare rainy evening, and as we reached the train station in the north of town a shower descended in force. We took shelter on the station steps. A man approached us, speaking good English. "I want to tell you that the Black people around here have their eyes on you," he said. "They're looking to steal from you. You must always be careful of the Black people in Cuba." Thanks for the information, we told him, hoping the sarcasm carried.

A little bedraggled, we closed in on Miguel's residence. There were no street signs at all in this part of town. In the dripping darkness we poked our noses into the living-rooms of houses, seeking guidance. Finally, after much head-scratching and backtracking, we found our destination. Miguel was delighted to see us. He introduced us to his wife, who was just leaving for a night's work on the railways. Miguel himself disappeared for a few minutes to ferry her to the station. In his absence, we chatted with Roberto and Rosalba, his father- and mother-in-law, with whom he had lived for the past ten years or so. Like everyone else in Cuba come evening-time, they were immersed in some dreary program on the black-and-white TV, and seemed grateful for the distraction of the visit.

Shortly after Miguel returned, Katherina departed to catch her train; we said affectionate goodbyes, and then I was left alone with the family. The conversation unfurled towards midnight, expanding on themes I'd discussed with Miguel aboard the train. For the most part it was a litany of frustration and criticism - but delivered with the strange panache that Cubans often bring to such denunciations. Rosalba, a stout and voluble woman, gave me my first look at the libreta, the ration-book that was as vital to Cubans as my passport was to me - more so. I flipped through it, noting the check marks beside goods received. Some commodities, said Rosalba, come only once every two or three months, some only once or twice a year - including such essentials as soap and cooking gas. But Miguel nonetheless considered the libreta "the strongest weapon of the state." It was the major means, he argued, of keeping the population in line - and also of keeping track of its movements, since if one changed residence one had to apply for a new booklet.

Rosalba brought me a document that was now no more than a historical curiosity. It was the ration-book for clothing, which was phased out in 1990 at the beginning of the período especial. Today, all clothing was paid for in dollars - except for the limited items available in pesos, at extortionate prices. "Three hundred pesos for a pair of pants - two months' salary for many people," said Miguel. "And the quality's lousy."

So what was the solution? For Miguel, it was a question of personal freedoms - of expression, travel, and most of all of economic activity. "Everything here returns to the state eventually," he said. "What incentive do people have to work and improve themselves, when they can't make anything more than the salary the state sets for them? And how can they learn how things are done in the outside world, when the media tell them only what the state wants them to know?" Sweeping political changes were necessary, Miguel argued: "We need a leader who knows how to listen, instead of just lecturing us hour after hour in the same old way." It was a viewpoint I had come to find increasingly persuasive over the course of the trip. No-one wanted to see the achievements of the revolution thrown out the window, sacrificed to the savage capitalism that prevailed in most other parts of the Third World. But the political and economic constraints placed on a free-spirited and entrepreneurial population seemed anachronistic, hard to defend. The malevolent policies pursued by the U.S. had only made it easier for the system's supporters to defend restrictions on liberties as necessary "emergency" measures. But the reasoning carried only so far. Personally, I found it more specious and self-serving than it had seemed from a comfortable distance.

A program started up on one of the two TV channels: a documentary about Pope John Paul's visit to Chile in 1987, in the waning years of the Pinochet dictatorship. It was a good opportunity to ask about the atmosphere in Cuba at the time of John Paul's four-day sojourn earlier in the summer. A wonderful time, they all agreed, and never more so than during his stop in Camagüey. The city lies at the heart of one of the most Catholic regions of Cuba, said Rosalba, and the Pope's visit occasioned a great deal of esperanza - hope - for the future. The family viewed the increasing religious tolerance of the regime with some optimism: "Before 1990, if you had parents who were known to be Catholics, you wouldn't be allowed into the university," Rosalba proclaimed. On the other hand, the opening during the Pope's visit was short-lived: the state media gave John Paul's visit saturation coverage while it lasted, but after he departed, it was as though nothing had happened.

Santería altar

Despite

their enthusiasm for the events, Miguel's family wasn't Catholic. Rosalba,

instead, adhered to santería, the religion developed by Cuban

slaves to conceal their traditional West African beliefs behind a Catholic

façade. Santería is tolerated by the revolutionary

state, probably because the diffuse amalgam of beliefs does not present

the same threat to Communist ideology that Catholicism does, with its time-honoured

support for reactionary forces across Latin America. Rosalba pointed to

a small shrine in the corner of the living-room, near the TV set, which

had escaped my notice to that point. It was an homage to Saint Lazarus.

The saint is twinned in santería belief with a Yoruba deity,

Babalú Ayé, who shares his curative powers.

Despite

their enthusiasm for the events, Miguel's family wasn't Catholic. Rosalba,

instead, adhered to santería, the religion developed by Cuban

slaves to conceal their traditional West African beliefs behind a Catholic

façade. Santería is tolerated by the revolutionary

state, probably because the diffuse amalgam of beliefs does not present

the same threat to Communist ideology that Catholicism does, with its time-honoured

support for reactionary forces across Latin America. Rosalba pointed to

a small shrine in the corner of the living-room, near the TV set, which

had escaped my notice to that point. It was an homage to Saint Lazarus.

The saint is twinned in santería belief with a Yoruba deity,

Babalú Ayé, who shares his curative powers.

I crouched down low to snap a photo, delighted to finally get a glimpse of Cuba's famous religious syncretism in practice. Just before midnight, I took my leave, with hugs and smiles all round. Perhaps one day, I said, I would be able to return the favour by welcoming Miguel for a visit to my own country ... Rosalba laughed fit to burst, and mimicked the posture of a doddering old crone: "Perhaps if I live to be a hundred!"

That was news to me - but when I thought about it, it made sense. The place was run by two men, both nearing middle age, living together without a girlfriend to be seen. In Cuba that was, to say the least, unusual. On my last day in town, I gathered up the nerve to broach the subject with Alfonso. As my final excellent dinner was being prepared by the matronly woman hired to do the cooking, I set down my copy of Edith Wharton's The Age of Innocence and blurted out the question: "So, you and Eduardo are a couple, right?"

He seemed only slightly taken aback. After a brief hesitation, he nodded. "Why do you ask? Are you one of us?"

No - but Alfonso was pleased to find a straight who was curious without being judgmental, and he answered my follow-up queries frankly. He and Eduardo were only in their late thirties, but they had lived together for eighteen years - tolerating the behind-the-back whispers that were an inevitable part of gay life in Cuba. "You have to understand that this is an underdeveloped country in more than the material sense," Alfonso said. "We're still not as ... civilized as you are in the west."

The situation had improved slightly over the last decade or so. Tomás Gutiérrez's film, Fresa y Chocolate (Strawberry and Chocolate), about the friendship between a straight and a gay in Cuba, was enormously popular at home as well as overseas. It had done something to humanize the country's gay minority. The fact that it had been made at all signified a liberalizing trend on the state's behalf. The discrimination Alfonso experienced today was not so much systemic as social. Still, it was hard to find places to meet and congregate. A couple of discos in Havana reputedly held "gay nights" once a week; but in a provincial centre like Camagüey, such early harbingers of enlightenment were still difficult to imagine. Gays met on the street, in the parks, or behind closed doors. They still risked being anathematized by their families when they made their sexuality known. Alfonso's family had come to accept his relationship with Eduardo, but it still wasn't something to be proclaimed openly to the wider society. For example, said Alfonso, a foreign tourist passing through had left him a couple of magazines of gay pornography: "But I couldn't take them down to the park to read, like you could in Canada."

I corrected him on that point - any homosexual openly thumbing through porn in a public place would risk derision, probably arrest, and very possibly physical attack. "There's a lot of violence, still, directed against gays in our country," I said, and Alfonso responded: "Here, too."

The subject being discrimination, I mentioned in passing the racist comments about Blacks which had reached my ears over the course of three-and-a-half weeks in Cuba. And here Alfonso shocked me. He shared those ugly viewpoints - even carried them a step further. "Look. You have your opinion, and I have mine. As far as I'm concerned, Whites are more discriminated against in Cuba than Blacks."

When I managed to stop gasping like a goldfish on a tabletop, I countered: "But look at the top leadership in this country. How many of them are Black?"

"Political power, sure," Alfonso responded. "But look at our athletes - the majority of them Black. Or our musicians."

Still flailing around, I asked: "But what about Nestor?" He was a Black guy who'd been a regular visitor to the casa over the course of my stay.

"Nestor's a good guy," said Alfonso. "But he doesn't like Blacks either. He considers himself a decent person - not like those negros in the street just standing around waiting to rob you. In my view," he continued, warming to his theme, "Blacks should have their own part of the country, and leave the rest to us."

Well, why not lock up gays in concentration camps while we're at it? - but I was too stunned to argue the point further. There was something insidious about the way Alfonso delivered his anachronistic perspectives without stridency or apparent malice. It was as though he were merely talking about facts of life. Somewhere at the back of my mind, a little demon whispered: "Well, that guy who tried to rob you in Havana - he was Black." And that, of course, is how the infection takes hold, and spreads.

I hauled my bags out to the living room an hour or so later and prepared to take my leave. As I did so, Alfonso was welcoming a couple of visitors - "My friends," he said, introducing me. "Do you know what I mean?" He had apparently dropped word that I was to be trusted, for as I left, the visitors were leafing animatedly through the hard-core porn magazines Alfonso had mentioned. I caught a brief glimpse of full-colour photo spreads: well-muscled young men sporting very prominent erections. The group winked knowingly at me as I headed out, for the last time, into the rain-slick streets of Camagüey.

I skipped a taxi and hauled my bags half an hour through the slowly-rising city to Felecia's place. Marco, the Spaniard, had left some days earlier, promising to return and renew his revels in a few months' time. I moved into his old room - a spartan affair, but away from the perpetual squawk of the T.V. It also had access to the tidy communal bathroom, rather than the grottier one I'd shared only with the roaches on my last visit.

Havana seemed tattier. It was partly due to the summer rains: they had arrived in force to turn the streets muddy and my part of Felecia's house into an island, separated from the rest by six inches of floodwater on the patio. But the city cheered me nonetheless. It was familiar territory. I knew where the best ham sandwiches and "pizzas" were found (I also knew I'd be living on them for the next three days). And I had no shortage of old friends and new to pass the time with around the kitchen table at Felecia's.

Banyen tree in Miramar

There

was also a fair bit left to do. On Friday I set out on a sun-dazed hour-and-a-half

trek across Vedado to the Río Almendares, which marked the frontier

with the upscale, leafy suburb of Miramar. Once free-spending Americans

had built palatial dwellings in Miramar; many were now occupied by foreign

embassies. I stopped in at the Canadian Embassy to see whether my craving

for news could be slaked; but there was only a well-thumbed three-month-old

copy of The Globe and Mail to be had. An embassy spokeswoman came

down to apologize: the staff regularly packaged up the embassy's newspapers

and magazines for Canadians who were passing time in Cuban jails. Most

were there on drug charges, naturally. While pushing the two most dangerous

drugs known to man - alcohol and tobacco, in the form of the country's

famous rum and cigars - the Cuban government had apparently decided to

follow most of the rest of the world in criminalizing more innocuous substances

like marijuana and cocaine.

There

was also a fair bit left to do. On Friday I set out on a sun-dazed hour-and-a-half

trek across Vedado to the Río Almendares, which marked the frontier

with the upscale, leafy suburb of Miramar. Once free-spending Americans

had built palatial dwellings in Miramar; many were now occupied by foreign

embassies. I stopped in at the Canadian Embassy to see whether my craving

for news could be slaked; but there was only a well-thumbed three-month-old

copy of The Globe and Mail to be had. An embassy spokeswoman came

down to apologize: the staff regularly packaged up the embassy's newspapers

and magazines for Canadians who were passing time in Cuban jails. Most

were there on drug charges, naturally. While pushing the two most dangerous

drugs known to man - alcohol and tobacco, in the form of the country's

famous rum and cigars - the Cuban government had apparently decided to

follow most of the rest of the world in criminalizing more innocuous substances

like marijuana and cocaine.

I had a pledge to fulfill at a house a few minutes' walk from the embassy. It belonged to Mayra, a middle-aged biology professor who had opened her doors to students attending the International Youth Festival held in Havana in 1997. Specifically, Mayra had sheltered a former student of mine, Paul, who'd passed on her address with the suggestion that I stop by.

Mayra, unfortunately, wasn't able to open her doors to me - not at first, anyway. She'd somehow managed to lock herself out of the house. The front gate was locked as well - so Mayra was marooned in the small garden between house and chain-link fence. She greeted me with hugs, kisses, and mortified apologies. A key, she said, was on its way. Finally I gathered up the nerve to climb the fence, narrowly escaping injury; a few minutes later the spare key arrived.

We sat in Mayra's nicely-appointed living room and talked over coffee and refrescos. For all the difficulties of life in Cuba, my host remained a staunch and cheerful supporter of the revolution. Part of the reason was arrayed round us. The house Mayra lived in had belonged to a wealthy Cuban who fled the country after the revolution. Until 1984, she had paid no rent at all. Now the government was charging her 28 pesos a month - a little over a dollar. I told her, to her happy shock, that such a house would cost her a quarter of a million dollars in Vancouver, perhaps much more. It was certainly likely to remain beyond my financial reach for as long as I lived.

Mayra's husband, Jésus, stopped in briefly to change clothes before heading back to work at a nearby luxury hotel. He was a tall, strikingly good-looking man, his age given away only by tousled salt-and-pepper hair. Jésus had spent a couple of decades in the Cuban army, before being caught in the wave of austerity-era downsizing that prodded him into the tourist economy. His service included a stint overseas with Cuban forces in Angola - during the crucial years of 1974-76, when Cuban soldiers repelled South Africa's attempt to replace Portuguese colonialism with a pro-apartheid regime, and stayed on to battle the White supremacists to a bloody stalemate. "If ever the real story of those years could be told, it would be something for you to read," Jésus said. I told him if he ever wrote it, I'd do my best to get it translated. He laughed, and fixed me a tall glass of rum and lemonade before heading back to the streets. On his way out the door he gave me his views on Cuba's present state. "We have a saying here that if something comes to you easily, you won't appreciate it. But if you struggle for it always, it will always seem dear. That's how we feel about our independence. Times are hard, but at least we can say we're not living under the heel of the U.S. any longer."

He left, to be replaced by a friend of Mayra's. She was a boisterous Black woman who immediately planted herself in front of the Daewoo colour T.V. Mayra joined her gleefully. For the next couple of hours, I might as well not have existed. The final episode of Las Aguas Mansas was being aired, and not just my companions but most Cubans were glued to the set. I half-watched the histrionics, leafing idly through the Vancouver picture-book that Paul had brought the family as a thank-you gift. A good thing I had only a few days to go before I'd be seeing that lovely city again: what with the rum, homesickness might well have overtaken me.

The bad guy died. The sundered friendships were repaired. The amorous couple got married. Las Aguas Mansas was done with. Mayra and her friend were already looking forward to the next telenovela, due to start the following week. It was called Café - another Colombian concoction, if you hadn't already guessed. The government was apparently careful not to leave much dead time between novelas, lest the masses rise up in rebellion.

A

last day in Havana, and in Cuba ...

A

last day in Havana, and in Cuba ...

I caught a rustbucket ferry from the harbourfront across to Casablanca, a neighbourhood at the foot of the ridge from which British forces shelled Havana into submission in 1762. (They held it for eleven months, evacuating only when the Spanish agreed to give them Florida in return.) The fortress at the harbour mouth, the Castillo del Morro, had been designed to render the city impregnable. But the British attacked from the rear and seized the commanding heights. To guard against any replay, the Spanish smothered the ridge after the British departure with one of the two most massive fortresses in all the Americas: San Carlos de la Cabaña. Once again, though, the designers had reckoned without the wiles of the foreigner: in this case the Canadian invader, who slipped into the castle from the rear, strolled past a sleeping guard, and managed to tour the place for free. For some reason - time, apparently - the ubiquitous tour buses made their morning stops at Castillo del Morro, the smaller and less impressive of the two fortifications. I had San Carlos almost to myself, and scampered about its massive walls, drinking in the magnificent skyline views across the harbour mouth.

With the sun sinking and rain-clouds looming, I tied up a final loose end of my journey: I paid another visit to Andrés and Carmen in the Old City. Carmen I presented with a few packets of Aspirin, to soothe what ailed her and her young charges, and also with my last bar of perfumed Camay soap. She cooed delightedly, and the three of us chatted the afternoon away. Carmen recalled the delight she'd felt, at age nineteen, when she witnessed the victorious arrival of Che and Camilo Cienfuegos, then Fidel himself, after the dictator Batista fled the country. The changes thereafter still commanded her unswerving support. "When I was a child I went to a Catholic school. I was the only Black student - because my grandmother had the money to get me in. You couldn't imagine something like that today. Just think, education free for all - from primary school right through to university. Is there another country in the world that can say as much?" Certainly not Canada, I conceded. For Carmen, the disillusion felt by many in Cuba reflected the unrealistic expectations of youth. "The young people don't know what it is to struggle, to sacrifice. All they can think about today are their Nike running shoes and fancy T-shirts."

I took a couple of snaps of the family, and we parted with embraces and promises to keep in touch. Promises to keep - and contacts to renew. I want to return next year to tour the eastern part of the island: the original base of European settlement in Cuba, the heartland of nationalist heroes from Máximo Gómez to Fidel Castro, and still, in many minds, the heartland of revolutionary sentiment in Cuba.

There is of course much left to explore in Havana as well. For one thing, I never ended up seeing that many-hued sunrise behind the Castillo del Morro that Marco insisted I stay up all night to catch. Hasta la próxima.

Back to a city that is in some ways what Havana would have been - would have continued to be - if the revolution had never happened. There are four million people in Guadalajara. In recent decades, the city has witnessed the kind of uncontrolled urban sprawl that has afflicted nearly every formerly-graceful big city in the Americas. Still, Guadalajara has done better than most - just as Havana had its comparative prosperity, however unequally distributed, before 1959. Guadalajara has elegant pedestrian malls, beautifully-restored 17th and 18th-century colonial edifices, and the pulsing commercial vitality of a great western city. On many levels it works. But then there are the corrupt, ferally abusive police; the street kids; the shanties. The sort of misery that's inevitable when half a country's population lives below the poverty line. Havana has its dangerously crumbling houses on the Malecón, and Cuba its hungry people - but in some ways it works where Guadalajara does not. In fact, Cuba provides services - or pays convincing lip-service to services - in a manner that no other country does, with the possible exception of wealthy Sweden.

One thing Guadalajara undeniably had that Havana didn't was reasonably reliable information: newspapers from all over the world crowded the stands, and there were a number of pretty decent domestic ones to boot. After a month stuck in Cuba with only occasional issues of Granma, probably the worst daily newspaper in the hemisphere, I feasted on the journalistic bounty. I'd had quick glimmers of trouble brewing with international capitalism, but the scale of the Russian crash and its global repercussions still came as a shock. So did the depth of Bill Clinton's travails with Monica Lewinsky - my, he was up to his neck in it, wasn't he?(4)

I realized that as an intellectual, it was the general paucity of information-sharing and debate that I would have found hardest to deal with in Cuba. It also struck me as increasingly indefensible, particularly in these hard times. Graffiti on the way to the airport in Havana proclaimed: "Cuba will not have a transitional government." And it was true that one needed only glance at Russia to see how calamitous a political transition could be when it became mired in corruption, outside manipulation, political fragmentation, and near-total economic collapse. But it was also true that oxygen was badly needed in Cuban politics and society. A good start, I figured, would be to shift Fidel Castro from his current dictatorial position in the hierarchy to a more symbolic behind-the-scenes role - the Lee Kwan Yew approach.

An economic transition also needed to be engineered, to remove the clumsy hand of the state from the micro-level of human enterprise, where it was stifling initiative and making life more tedious than it needed to be. This seemed to me the only fair palliative for Cuba's basic economic contradiction, as Yasmin had expressed it to me eloquently early in the trip. If you were going to charge citizens hard currency for many of the goods they needed - needed if they were not to lead lives of humiliating austerity, at least - and if you were not willing to pay them in hard currency, then breathing-space had to be granted to let people make their own way. They needed to be able to expand their choices at the level of basic consumer goods, through competitive pricing of imports; and domestic industry needed to start producing, for profit, a range of consumer items that were presently imported and priced through the roof. Crackers, for God's sake. Finally, people needed to be taxed on the income they earned. No prohibitively high, year-round licensing fees for rentals of private accommodation, which is of course subject to the same boom-and-bust seasonal cycle as the remainder of the tourist economy.

For some of this to occur, Castro probably has to go. But he should go, it seems to me, with considerable plaudits. He is certainly the greatest Cuban nationalist figure of the twentieth century. He is one of the few effective, internationally-popular voices raised against the global neoliberalism that enriches a few and immiserates millions. And the system he had put in place in Cuba still has enormous strengths. The commitment to health care and education, the internationalist impulse that had kept Angola out of South African clutches, the proud and defiant nationalism - all have entrenched themselves deeply in the Cuban consciousness. Even vociferous critics of the system, those who stress its police-state character, preface their comments or append to them something along the lines of, "Of course, we wouldn't want to be without ..." It would be a great shame - a disaster, in fact - if these aspects of the revolution were to be dislodged from their place in the hearts and lives of Cuba's citizens. One would rather wish to see them praised to the skies, and universalized before it is too late.

In my view, no-one should call for political or economic change in Cuba without also condemning the ruinous embargo the United States has imposed on the island. As David Stanley aptly writes, "It's hard to think of a foreign policy area where U.S. politicians have gotten it wrong so consistently for so long." The United States would be better advised to take a leaf out of Cuba's foreign-policy book, and to send doctors, teachers, and construction workers en masse around the world, instead of cruise missiles. As long as the U.S. stance towards Cuba is a hypocritical and vindictive one, it should be vocally countered by the western democracies, as well as by those Third World peoples who still see Cuba as a beacon. Why, after all, does Fidel Castro get a hero's welcome in every country of Latin America - even in the streets of Harlem? Because tens of millions of people in those countries and around the world consider his hopes for humanity a good deal more persuasive and sustainable than any vision U.S. governments have put forward.

Castro's Cuba is one thing, the people's Cuba somewhat different. Ideology remains important for some, and state services for many, many more. But it is above all the resilient bonds of family, community, and mutual support that have allowed Cubans to weather crises of a kind and a scale that have shattered other societies. These bonds do not seem on the verge of sundering anytime soon. As long as they hold, Cuba as a whole will endure. It deserves to. It has been through a great deal, and still suffers mightily.

The tensions of Cuban politics and society have given these journal pages their often-ambivalent tone and character. Perhaps that is inevitable; anyway, it seems appropriate, given the uncertainty of these moments in the island's life. But I can report very little ambivalence about Cubans themselves. They opened their homes and lives to me as few people have. That Cuba, I hope and expect, will survive.

Naptime in the daycare, Trinidad

2. See <http://www.lonelyplanet.com/letters/car/cub_pc.htm>.

3. See <http://www.geocities.com/TheTropics/Shores/5902/transport.htm>.

4. Or hers, adds my father (November 1998).

Created by Adam Jones, copyright 1998. No copyright claimed for

non-commercial use of text or images if author is credited and notified.

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

Last updated: 10 October 2000.