Vibration Land:

A Journey through South China

Part Two

by Adam Jones (1984)

Sjors and Marvin, Guilin to Kunming

Anning

Kunming/Shilin/Emei

Leshan/Chengdu

Chongqing

The Yangtze to Yueyang

Not Changsha

Shaoshan

Dreams of Home

IX. Sjors and Marvin, Guilin to Kunming

Second-class aboard a Chinese train.

The

rail journey involves one of those tortuous Chinese detours - a stretch southwest,

winding northwest to Guiyang ("Although many travellers pass through here,

they are not in theory permitted to leave its cavernous train station").

The terrain is so inhospitable that until quite recently the main line

of communication from Southwest China to the rest of the nation actually

ran through Hanoi.

The

rail journey involves one of those tortuous Chinese detours - a stretch southwest,

winding northwest to Guiyang ("Although many travellers pass through here,

they are not in theory permitted to leave its cavernous train station").

The terrain is so inhospitable that until quite recently the main line

of communication from Southwest China to the rest of the nation actually

ran through Hanoi.

The trek ends with a shallow southwesterly

passage across high hills into Yunnan Province the rugged bulge, scored

by jagged ranges, which arches down from neighbouring Tibet. Then you're

in Kunming. It takes 35 hours.

It should be excruciating: by a small margin

the longest train ride I've ever taken, through impassive winter-brown

scenery. But I'm reckoning without bumping into Sjors at dinner. He and

the Kiwi, Marvin, are heading my way, and we hook up.

They are two real travellers. I realize

that as we're sitting in our comfortable hard-berth seats, waiting for

departure, when Sjors smiles and says: "It's not like the train from Khartoum

to South Sudan."

"I beg your pardon?"

He grins, but he isn't bragging. Time on

the road shakes the most entrenched ego: there's always someone with a

better story than yours.

"Sudanese trains are very interesting.

Often there's only one a week to the south. I arrived eight hours before

it was due to leave, and it was impossible to enter the station. Impossible.

Two people died on our journey. It was too hot, forty-three or -four during

the day; at night half the people in the train would move to the roof,

because it was cooler. There'd be gambling and arguments and knife fights

up there. Two dead." He smiled and glanced around the carriage. "If this

were India you'd have people sleeping on the luggage racks."

Sjors has the Western European youth look:

intellectual, with round steel-rimmed glasses and hair cut choppy-short,

a few days' growth on his chin and lip. Tall, lanky, fit. As a Dutchman

he falls prey to my pet stereotype:

DUTCHMAN. Member of national

group characterised by tendency toward comfortable scruffiness and a facial

expression of tense hilarity. Fond of words containing odd "oor" sound;

this, when combined with muffled speech caused by ubiquitous protruding

cigarette-end, adds to image of eccentric "funkiness" (cf. "funky").

But Sjors doesn't smoke - "Tobacco," he emphasizes,

with a quick, tensely hilarious facial expression.

He's been on the move for fourteen months:

seven in Africa, then India, Nepal, Southeast Asia. Fourteen months - and

here am I cursing impending burnout after a couple of weeks! When the lights

go out in the compartment, he crosses his legs into a graceful full-lotus

and meditates. Marvin and I call him George, and make comradely fun of

his Dutch accent ("Hey, George, don't forget your yacket!"). At this Sjors

smiles patiently, knowing his English is better than ours. He picked up

most of it travelling. That, and French: "When you're very far from anywhere

in Africa, you just to go the nearest group of huts, and you ask for the

chef du village. He normally knows a few words of French or English and

he will fix you up with something."

Sjors is 33, and it seems as though he

could stay on the road forever. Marvin has his share of stories too, but

no patience for forever. He's simply taking a roundabout route home to

New Zealand. His eyes shine happily as he talks of his future: getting

low-interest loans, making a stake on some land bought for a tax dodge,

doing it his way and making the most of weekend recreation opportunities

in that beautiful country.

It is hard to quibble with his dreams of

settling down somewhere, because Marvin save for one three-month whistlestop

in N.Z. has been away from home for seven years. Most of that is solid

travelling. Every thread in his backpack can tell a story, and he proves

more loquacious than Sjors.

In Mr. Huang's restaurant, we tiptoed around

each other. I got off on the wrong foot with, "Are you from Australia?"

and saw his eyes twinkle with, Who is this little shit? But I covered my

tracks and eventually got him going. Now we talk earnestly, sometimes intensely,

well into the carriage dark of that first night, rocking along tracks that,

at this early stage of the journey, are bearing us in precisely the wrong

direction.

He was born 30 years before in the once-insignificant

Falkland Islands. "I didn't follow the war much. I left for New Zealand

when I was nine, you know? Not many ties." He has a pleasant, slightly

self-mocking way of speaking, and in the dim light he looks younger than

his years. You can't see the lock of grey hair curling over his forehead,

or the few strands in his neatly-trimmed beard. His eyes are still full

of the mischievous high-school student who raced with the "English motorbike

crowd" Down Under.

Marvin had skipped the university scene

and dived straight into the construction business. That landed him a two-year

stint in Papua New Guinea. "They say if you're a white in P.N.G. you're

one of three things: a mercenary, a missionary, or a misfit."

"What were you?"

"Sort of a mercenary misfit."

His best stories come from five years ago,

an epic overland jaunt through West Asia and Europe. First leg: Pakistan

to Istanbul via Afghanistan ("After the communist coup, but before the

Russians arrived") and Iran. "When I was in Pakistan I had three hundred

American dollars to my name. That bought me a month in Pakistan and a ticket

straight through to Turkey. I was expecting a cheque in Istanbul; when

I got there I had sixty dollars left. And there was no cheque, was there?

So I bought a ticket on the cheapest ferry across the Bosporus and hitched

down the coast. All I bought for food was these huge loaves of bread, feta

cheese and tomatoes. Dead cheap, and lovely stuff. My Feta Trek."

"Where did you sleep?"

"Olive groves. Hitched along in vegetable

trucks by day - the kind with the wooden cabs? I ended up on a plateau just

above Gallipoli, where the Anzacs caught the shit in the first war, thanks

to the young Mr. Churchill. I was sitting in a teahouse - that's how I used

to pass the hours between dusk and bedding down, you know, go to a teahouse

and buy a thimble of tea, and the locals would usually stand me a couple

more. This Turkish bloke asks me where I'm from. I knew the Turkish for

New Zealand. A little later he took off, and I thought he was leaving for

good. But half an hour later, back he comes with this little tin badge.

An Anzac crest from 1915. He'd ploughed it up in his field. It had a globe

turned to show Australia and New Zealand rather larger than scale, and

a wreath of olive branches. I sent it back with my coin collection to N.Z.

I'll never know what Anzac lad it belonged to. But after all, it got home,

you know? Back home.

"I hitched from there back to Istanbul

and cashed my last ten-dollar travellers' cheque, having no idea whether

my money had arrived. But it had. I was rich again, and I headed to England

for Christmas."

He pauses for tea. Together we eye the

Chinese in the bunk opposite us. Parents and progeny: two dull, thick-faced

peasants with an utter monster of a son who squirms over the bunks wearing

an expression of extravagant boredom. With government pressure to limit

families to one child, the lucky offspring can be shamelessly spoiled in

China (or, alternatively, drowned if it's female and the family wants their

sole kid to be a boy). Rosemary's Baby here obviously learned early on

that shrill screams of protest, accompanied by judicious secretions from

his bottomless tear-ducts, could bring him the world on a platter. He sends

shivers down my spine.

"What a wingeing fucking brat," Marvin

says amiably. The child looks at us with mingled mischief and suspicion:

You're not going to spoil my game plan, are you? His pudgy cheeks are caked

with grime and tiny pustules, but whenever Loving Father tries to clean

Precious's face, Precious writhes and screams with transparent but ear-shattering

hysteria, which ceases the instant the offending cloth is withdrawn. Snot

trickles in a dirty stream from his nose. He chews sugar cane and spits

the fibre on the floor. I find myself loathing him with exhilarating intensity.

"Monster!" pronounces Marvin emphatically.

"Anyway. England. Actually, I didn't go there directly. I spent time in

France picking grapes. We were right up in the Pyrenees, four of us in

a little rustic old stone house. Me, two Frenchmen, and a Portuguese. We

used to get up at the crack of dawn and have a big bowl - a bowl! - of coffee

and some bread. All except the group's resident alcoholic, who would polish

off the dregs of last night's wine. We'd pick all morning and then give

one of the fulltime workers some money to go into town and buy bread and

sausages. When he got back we'd set some grape vines alight and roast sossies

for lunch. Then pick all afternoon, 'til five or so. A long day, but we

were paid by the hour, so it was alright. In the evenings we sat around

the fire and maybe a few other pickers from other farms would come over

with their house wine. I did that for a month-and-a-half, and then figured,

hey, I'm in the Pyrenees, might as well move around a bit. So I hitched

to Andorra, and the people who picked me up -"

I stop him and say, "You little bastard,

if you shit on the floor, I'm going to kick you out the window. Oh, God."

Marvin turns. Rosemary's Baby is squatting

in the aisle while his parents blithely peel oranges and stare at the landscape

outside the window. A stream of urine comes from between his grubby legs,

through the slit in his trousers provided for this purpose. It forms a

pool on the floor. The demon's face remains blank: Well, whaddya expect?

When you gotta go ...

"I don't believe it," Marvin says softly,

but his words turn to a yelp when the rocking of the carriage sends a river

of piss flowing under our seat. Where he's stowed his backpack.

He is up in a second, and the pack, its

base all damp, is pulled out. "You fucking little shit!" he bellows. Then

he turns his furious glare on the bewildered parents. "Right, see how you

bloody like it!" And he grinds the pack into the sheets of their lower

bunk, leaving lovely spreading stains. The parents look at him with their

bland peasant faces, then glance down at their sheets, still uncomprehending.

"If he wants to do that he can go to the

toilet!" I say in my best angry Chinese.

Father doesn't know what to do. He picks

up the little empty-bladdered troll as though holding an egg on a spoon:

is he supposed to start learning how to scold, at this late stage? Heads

in the carriage are turning his way. He is embarrassed and perplexed.

But Quasimodo knows what to do. He scans

the two murderous white faces, one with a fearsome beard, upturned to him;

and he lets out a fearsome howl, which we fuel further with angry and mocking

expressions until it fills the carriage like every primal scream in Arthur

Janov's casebook combined. That's something Dad can relate to. The Spawn

of Satan is back in control. He burrows into the strong arms that hold

him, and the air-raid siren and tear-duct faucet are turned off suddenly,

simultaneously.

"He knew exactly what he was doing," Marvin

fumes. "He's old enough by now."

Sjors, by the window, watches the scene.

He smiles the smile of someone who's seen it all, or at least enough not

to be bothered by a bit of piss.

A little later, when things have calmed

down, I say: "Andorra?"

The train is moving into higher altitudes

now. A fleece of dusty snow covers the hills, gleaming in the moonlight.

A few bumps of winter vegetation show through.

"Yeah," says Marvin. "Well. The people

who picked me up gave me a little cube of hash to keep me going. So I wandered

around Andorra stoned out of me mind. Nothing doing at all, just a lot

of hotels and duty-free liquor and film shops. Dead boring. So I hitched

back into France the next afternoon, and got a lift out of Toulouse with

some students who were headed all the way to Paris - which was perfect, 'cos

I wanted to get across the Channel. We drive on and a few minutes later

I hear these rustling sounds and then the car is filled with the smell

of dope. This girl turns around with a huge spliff and says, 'I hope you

don't mind the smell of this?,' and I pull out what's left of my chunk

and say, 'Not if you don't mind the smell of this,' and away we

go.

"So we rolled some cocktails, a little

of each, and drove stoned to Paris - stopping to sleep for a while, 'cos

it's a long ride - and on the way they did a little shoplifting, bread and

candy mainly. When we pulled into Paris I told them I wanted to catch the

boat-train to London, I could sleep on the boat a bit. So the girl says,

'Well, here's something to keep you going,' and hands me one of those little

plastic Easter-egg things. When I cracked it open it was full of grass.

There I was, leaning out the window of the train, smoking all the way to

the coast, then on deck across the channel. Had to toss the rest away before

we reached Dover.

"When I pulled up at customs I'd been smoking

for two days straight and my eyeballs were hanging down to my shoes. I

had long hair and it was a while since I'd seen a bath. So lovely England

didn't want to let me in even though I had a Brit passport. Didn't like

the looks of me, did they, and I had no money. I sat there spinning yarns

about vast amounts of cash waiting for me in London. 'Why else do you think

I would come to this bloody country??' That was something they could relate

to, I guess, and they let me through. I got to London and headed straight

for Halsted and kind relatives. Knocked on the neighbour's door first by

mistake, and they passed me along - so when the rellies opened the door they

couldn't claim to be Mr. and Mrs. Blogg who'd never set eyes on me in their

lives."

I am getting dizzy. But Marvin is on a

roll. More tea is poured, more nasty comments exchanged about the little

abortion now asleep across the way.

"England was too bloody cold. So I split

for the Mediterranean again and worked my way round to Israel, killed six

months on a kibbutz. My last week in Israel, way down south in a town called

Ashqelon, I was camping on a beach. I went 25 yards from my tent to wash

some shorts and some guys crept up, keeping the tent between me and them,

slit it open with a piece of glass and nicked my money belt. That was my

passport, travellers' cheques and plane ticket to Cyprus - all gone.

"I had 40 Israeli lire in my pocket. About

40 cents. I'd bought two days' food for camping. I had to get to the embassy

up in Tel Aviv. I hitched in on a Saturday - Sabbath, everything closed,

and the embassy was shut Sundays too. I ended up walking the streets of

Tel Aviv at night until I found a house no-one was living in - I could kip

there, and there was even a cupboard with a lock where I could stow my

bags. And then, wouldn't you know it, the Monday was August 1st, English

Bank Holiday, and the embassy was shut tight.

"Finally. Tuesday. Slicked my hair down

for the interview. Catch-22: I couldn't get traveller's cheques without

a passport, and couldn't get a passport with no other identification at

hand. Finally the bastards gave me one - on the basis of a bloody student

card I'd bought from a crooked Chinese cop in Singapore. All 'cos it had

a photo and a signature I could reproduce. That's the way people are sometimes,

you know. So bloody obstinate they're just begging you to pull a fast one

on them.

"It was another week before I could get

money through. The bank advanced a few dollars, enough to bed down at a

hostel for a couple of days, 'cos by that time I badly needed a shower.

At the hostel I met this girl who was working, getting straight room-and-board

for two hours of toilet-cleaning in the morning. She was quitting. I went

to see the old lady in charge, and I took over. I did that for a week and

a half, until my money arrived, and by that time they were asking me to

stay on! But I'd had enough, went to Cyprus, stopped at Larnaca for a beer,

on to Rhodes - touristy; nice castle, though - then to Marmarus, southwestern

coast of Turkey, crossed to Samos and a couple of other islands also ending

in 'os,' finally to Piraeus. Hitched through Greece, Yugoslavia, into Austria -

bad weather there. Saw a friend in Switzerland. Shot through France, took

the boat from Oostende, and caught the first direct flight back to New

Zealand for my three months' break. And that was that."

He talks quietly about home. "I can settle

there, I know," he says confidently. "It's the quality of life. There's

plenty of fishing and sailing and shooting and diving. And skiing! You

don't have to go a thousand miles to get them, like in Australia.

"Seven years on the road is enough. Sometimes

you find yourself wondering, 'Shit, what am I doing, wasting all this time

and money, sitting in this hole?' Granted, that's when you're miles from

anywhere and fed up. It doesn't last."

He plans on spending just long enough in

Hong Kong to load up on electrical gadgets and appliances. "Stereo unit,

a pressure cooker, toaster. All the crap you probably have in your kitchen

and don't think twice about. All the things you need to set up a home."

He smiles. We both grow thoughtful at the

incantation of the magic word: Home.

The train has stopped at a nowhere station

in the mountains; the altitude is enough to tickle my clogged sinuses.

It's very dark, only a few fields visible through the ghostly pallor. But

there is Home out there, too: a squat, sturdy little stone house, set back

from the station shack, perhaps 50 feet from the train window. A chimney

pokes through the shallow slope of its roof, and smoke curls lazily away

into the evening chill. A bright light shines behind translucent window

shades. No shadow of movement inside; no movement anywhere, apart from

the twisting tendrils of smoke.

X. Anning

It's a very lovely day in Kunming; we have

a room of unadulterated luxury in the city's best hotel to return to. And

here we sit, Sjors, Marvin and myself. Waiting for the inevitable bad news.

("The Kunming Public Security Bureau," notes my guidebook, "has the reputation

of being very helpful with travel permits and visa extensions.")

"Mr. Jones?"

"Yes?" I leap up hopefully from the propaganda

magazine I've been studying: smiling Han peasants, smiling minority peasants,

smiling Han and minority peasants working together for socialist modernization.

"Jinghong and Dali are both closed. But

you can go to Emei Shan and Leshan."

I begin to whine. "Why is it possible for

tour groups to go to Jinghong, but not individuals?"

"Ah! You see, tourist facilities are very

limited there. If we keep it to groups we can control the numbers more

easily." Her tone adds, "You could have asked me something a little harder."

She is a pleasant girl, with fine clipped English, and no fun at all to

argue with.

I say, "Oh."

There, in one fell swoop, goes my planned

detour to the tropical paradise of Xishuangbanna, nestled in the far south

of Yunnan Province near the Laotian border. Jinghong is the gateway to

this region, which was once the most remote, far-flung corner of the Chinese

Empire a real hardship posting for hapless Han officials. "The Kunming

authorities usually give permission for Jinghong routinely, but have sometimes

been known to be capricious ..."

There, too, goes Dali, my backup choice:

a town two days northwest of Kunming by bus. Mountainous and picturesque,

it had been the capital of the independent state of Nanchao, which had

crushed encroaching Han armies and sent them scurrying back to less hostile

environs.

But, the girl assures me, I can still head

north to the Sacred Mountain, Emei Shan, and freeze my balls off, and stare

at the ice-encrusted footprints of however many "lone wayfarers" have passed

the same way in the preceding hour or so.

Marvin and Sjors don't even bat .500 with

their selection. They'd requested permits for cities along the approach

routes to Tibet. This is rather like asking for papaya in a restaurant

in Reykjavik.

"Mr. Marvin, all routes to Lhasa are closed,"

the officer intones. This time the tone in her voice adds, "And you jolly

well know it." The closest Mr. Marvin will get to Tibet is reading the

relevant section of the guidebook, which exults, "Tibet is more accessible

to foreign visitors today than it has ever been."

"Xinning too," the girl adds. That's the

capital of Qinghai Province, where China's hardened criminals are sent

to build railroads; it has a flourishing Tibetan population. "Plus Jinghong

and Dali." About four out of ten are granted Marvin. Sjors fares no better.

"Of course, I understand," Marvin tells

the girl soothingly. "Those sort of places are interesting. You wouldn't

want us going there."

"I beg your pardon?"

"Fucking China," Marvin mutters, outside.

"It's the big-city tour. Everyone keep in line, please. Do you plan to

give Dali a go anyway?" We have heard of people who take the chance on

visiting off-limits sites without permits. Sometimes you get arrested.

Sometimes the police only come and ask you to change hotels. You hear about

people like this every so often. They're the ones who make it to Lhasa

by hitching in from Liuyuan in the north or Chengdu in the east - ten days

to two weeks by truck convoy. They're the ones that not only manage to

get to far-flung Kashgar, nestled in Xinjiang's remote western deserts

but bus their way back to the capital, Urumqi, via the southern route,

counterclockwise around the Tarim Basin ... right through the area of Lop

Nur, China's top-secret nuclear testing installation. That makes for a

couple of weeks' thoroughly unique travel through desert wastes. It can

also make for imprisonment and expulsion.

"I dunno," is my reply to Marvin's question.

But I do. If it weren't for my thick sheaf of scribblings, I might risk

it: foreign students are the closest thing to sacred cows in China. Maybe

once I have the notes typed up and out of the country - maybe then I'll give

the hitch to Lhasa a shot, just to see how far I can get. At the end of

my planned summer travels, when getting expelled would just mean saving

money on a train ticket out.

Still, if the bureaucratic axe has to decapitate

our travel plans, it could happen in a worse place than Kunming. This is

the "City of Eternal Spring," as every Chinese I've met over the last two

weeks has reminded me. I'm hoping for a day's snowfall or at least a patch

of dreary weather, just to puncture the cliché: it would be nice

to send Kunming's 2000-year-old reputation straight to hell. No such luck.

Kunming is fantastically sunny, spring-scented, with just a hint of smokestack

lavender. I know I won't be able to say much against it. (After the musty

refrigerator of Yangshuo and the deep freeze of a Guilin night, I would

have a few good words to say about Hades, with special mention to the guy

running the central heating.)

But we all need a break from cities, and

the small town of Anning Hot Springs beckons. There seems good walking

to be had - Sjors, fresh from a trek in Nepal, is positively rubbing his

hands at the prospect - and we can perhaps return via Lake Dianchi, the sixth-largest

dab of freshwater in China.

We agree on an early start, eat a huge

meal down the street from the hotel, nibble some fatally grimy cheese bought

at a local market, wash it down with suspiciously flat beer-on-tap, and

retire early to the splendour of our room: a bath, even towels to go with

it, for four Yankee dollars a night! I bed down, satiated. Around midnight

I wake with a reflexive crimp in my sodden bowels. I hustle to the toilet

and shudder with the first liquid convulsions of ...

The Shits.

When a traveller in Asia uses this phrase

it is accompanied by a tone of reverential, almost superstitious awe.

By the time dawn turns the curtains grey

- late, because it's officially winter, and Kunming in the distant southwest

runs on the same clock as Beijing - I am feeling run over by a truck. "I

think I'll give Anning a miss today," I proclaim through clenched teeth.

"Ah, come on," says Marvin.

A couple of hours later we are bouncing

through pretty fields of shining green to Anning proper, where the bus

stops. Marvin has come down with something nasty, too. A bacterial reaction

is inflating his gut like the Hindenberg. He sits rigid, praying that the

jouncing of the bus won't dislodge the iron grip of his sphincter. Sjors,

healthy and cheerful as ever, looks out the window. We suffer in silence,

just to spite him.

Marvin holds out, and at a noxious public

toilet in Anning we find temporary relief. "Christ," Marvin groans. "When

I let go I thought I was going to fly around the place like a fucking balloon."

We still feel lousy. My fingers tingle and turn nearly numb for no reason

whatsoever; I shiver in the morning shade of the street.

Anning is a hole, a dull dustbowl of an

industrial suburb. The locals can provide us with no consensus position

on how to get out of it. Up and down, hotel over there no, over there no,

we don't take foreigners, workers only. Finally a group of truck drivers

agrees to get us up to the hot springs a little in advance of the public

bus. Sjors, full of bounce, says he'd rather walk. Off he goes.

Marvin and I sit in the cool bus station,

drinking tea and hot water respectively, waiting for the truck drivers

to get their act together. Bitching.

"It's bloody fatal to come here after India,"

Marvin rants. "There's life in that country, you know? And colour, and

contrast, even if it is as poor as shit. And you can go where you want

and do what you like. Free enterprise: if barriers come up, a little palm-grease

straightens things out. This - China - it's just blue clothes and green clothes

and brown fields, and they won't bloody let you go anywhere it isn't."

I am up to the challenge. "I'm only beginning

to realize how incredibly dreary the life of the average Chinese is! No

room for initiative or ideas or real fulfilment. God," I moan, "sometimes

I want to grab people here by the neck and say look, you're boring, you were

born boring, you live boring, you'll die dull and unremembered." I pause.

"Well, there's the old western arrogance slipping in again."

Marvin nods. "Doesn't matter if anyone

remembers you or not. But do you want to go through your whole life like

a sheep in a flock, herded this way or that? By a herder whose right hand

doesn't bleeding know what the left one is doing?"

Virulent stuff. But a cure is just seven

or eight clicks up the road. We end up hitching to the hot springs, with

the "truck drivers" as fellow passengers in a Toyota half-and-half (had

it all been a translation error on my part?). "No-one allowed in the back,"

says the driver gruffly to milling, hitch-hopeful locals. Then he showers

me with the rote compliments about my Chinese. I listen gladly: we're on

the move again. There's sun-splashed greenery all around, and my elbow

is catching a tan out the window.

There is a nice old policeman at the hot

springs. He has a rifle that looks like a World War One Lee-Enfield propped

in the corner of his office; he bumbles about registering us and then passes

us over to the local Guest House crew. We end up with a tidy, comfortable

room for two dollars - split three ways. "God," marvels Marvin. "You can

keep your Hiltons."

Sjors happens along, exuding vigour from

every pore. I head across the street to the springs themselves, and bathe

in a private sunken cubicle, the water so hot I nearly faint. Then I sleep

for three hours, eat my first food of the day as the afternoon fades, finish

off Kerouac, sleep again. My bowels are blessedly quiet all night. When

morning comes, bright and blue, I'm ready to explore.

Anning Hot Springs is a road in and a road

out, with a guest house, a bridge where a few noodle-sellers ply their

trade, a couple of shops with whimsical business hours, and the springs

themselves. All these are jumbled together at a single paltry intersection.

But that road out winds like a dream along a sleepy river to a quiet valley,

a mile or two further on. The three of us set out, clad in wool jumpers,

into the impossible blue of the day. We stroll along the banks of the river.

The water glistens over shallow rapids like green jello; it seems to wobble

above and foam below with no movement in between.

There are few people along this stretch.

Some peasants tug produce to market, a few of them sporting the distinctive

dress of Yunnan's minority population. Half of China's 55 minorities are

found in this province. The largest group is the Dais, ethnically linked

to the Thais. Xishuangbanna, bless its inaccessible soul, is loaded with

them. There are no people in the fields, which on this day shine an almost

surreal green.

At one point Marvin looks up. "I'll be

damned. Eucalyptus. Australian gum trees." They grow spindly but leafy

at the side of a branch road leading to a squat local school building.

A group of woodcutters lounges by their freshly-hacked logs at the side

of the road. They regard us with a determined lack of interest.

"The universal test for gum." Marvin pinches

a leaf from a branch, rolling and crumbling it between his fingers. He

sniffs, offers it to Sjors, who nods. Then he holds it under my nose. Cool

and sharp and fragrant. "Nice."

"These things are everywhere in Aussie.

They have a tremendous ability to store water."

"Any tree that grows in Australia had better

have a tremendous ability to store water," I comment profoundly.

We walk on, and a few minutes later, Marvin

says, "Buds. God. It's springtime." Delicate little trees with branches

like a cypress are positively streaming with nodules. I give up and acknowledge

the City of Eternal Spring - after all, we're only an hour's drive away - for

what it clearly is.

Marvin decides to head back to the hot

springs for lunch and a potter around some adjacent villages. Sjors, ever

indefatigable, is off to try to climb the tallest mountain in the area.

"Drink a beer for me when you get back,"

I command Marvin, smiling. Our stomachs are now up to it. Barely.

I follow the road alone into the mouth

of the valley. Tall scrubby hills like yeti scalps rise from the uneven

floor. There isn't much cultivable land around here. Yunnan, three-fifths

the size of neighbouring Sichuan Province, can support less than one-third

the population. Even the terracing has a lopsided look to it.

I close my eyes and breathe in every farming

valley I've ever hiked in springtime. The smoke of burning compost, the

air that comes laden with a profusion of subtle aromas; sweet bloom and

growth everywhere. Even my snotty sinuses are impressed. I cross a high

railway bridge with erratically-placed concrete slats, and watch the green

floor of the valley blur along with my stride. A fierce breeze gusts, and

I feel a wave of vertigo ... it's a long way down. On the other side a

crazy trail snakes around the valley's central ridge, through verdant fields

of crabgrass.

A village of red and brown buildings skitters

up the hillside ahead. Oxen grazing, ladies in very blue silk headdresses

washing clothes in a massive steel tub, gossipping. On his flat concrete

roof, a man catches the rays, fending off the playful pestering of his

young son. (When I write that down in my notebook, it comes out as "young

sun"; with a start, the day seems to come fully alive.) The man shields

his eyes from the glare, not noticing me watching him from the trail above.

Around the bend another man hauls a small cart of logs laboriously up the

track, away from a stagnant pool.

"Need some help?" I call.

He smiles and nods. We pull together on

the worn leather strap, and the rickety apparatus bumps up the slope.

"Been walking long?" he asks. He is a peasant

of unguessable age: a dark lined face, sparse black bristles on his chin.

"Been walking long?" not, "Where are you from?" or, "How old are you?"

or, "You speak Chinese very well."

I shrug happily. "Just walking!" And off

I go, turning to see him push on alone. I feel a brief twinge in my heart.

I imagine helping him lug those logs all the way back to his house. Maybe

I'd be invited in for tea and a smoke. I haven't had much contact with

Chinese beyond the shallow bureaucratic level for some days. That can happen,

when you latch onto a couple of fellow westerners going your way; when

you can cut loose and gab without having to sputter monosyllabically around

every topic of conversation. Well. People are people. And a good yarn well-spun

is a good yarn, no matter from whose mouth it comes.

I sit down for a rest by the side of the

track, careful not to sit in any freshly-deposited oxshit, and do some

scribbling with the occasional jangly tones of cowbells for company. A

few village youths drive a dozen powerful-looking oxen up the path to their

grazing fields. Clouds bend their heads and charge along with the fresh

breeze. "Birds twitter and dive" (The Rustic Life and How To Write About

It, 3rd edition, p. 179). There is an invisible stream somewhere nearby,

scraping rustily along at the foot of a terraced slope. Above, way above,

thickly-forested hills stretch as far as the eye can see. The sun, hot

on my back, sends shifting shadows of cloud flowing along the valley floor;

they disappear out of sight behind the bend below.

Sun and oxshit and buzzing flies and twinkling

butterflies. I recline for a while and let the wind rustle my grubby jeans,

whistle up my nostrils; let the sun sting my face, turning it prickly and

tender.

When I chance to look up, a woman in ragged

clothes is picking her way gingerly up the terracing to a huge bundle of

wood. It's as tall as she is, with the girth of a fair-sized California

redwood. I say out loud, "No," just for effect, then watch resignedly as

she ties a couple of thick pads around the load, another around her forehead,

and sits back on the terrace to make necessary adjustments to the fastening.

She stands shakily and trods with indomitable resolution back down the

hillside. From the rear, she is just a mass of branches borne along by

two feet in tattered shoes. It is rather awesome.

There are fields of long grass and green

weeds with a few brilliant daises scattered in between. The old abraded

path still leads me up, at a shallow grade ideal for meditation. Feel your

lungs fill. Your step sure and even. A thin, deceptively fragile stick

whispers at my feet: Um, I know I'm not much, but I'm just the right height

for you; won't you take me on your walk? We march along together, leaning

on each other. It is flexible but resilient, and it tells me its story

in the scars left by a woodsman's knife that has stripped it of its bark.

It leaves a dusting of yellow sap on my palm. I fall in love with it. (And

a day later I leave it, propped against the wall of the bus-station noodle

stand. Absent-mindedness beats mystic attachment every time.)

Near the summit - by now I am beginning to

hope it's the summit - the foliage grows dense, the path strewn with chopped

sticks, stripped down and discarded. Pine needles, pine cones, pine branches

the whole forest reeking of pine sap. I squat in a little nook off the

trail and deposit some diarrhoea, then blow my nose in classic Asian fashion:

finger pressing one nostril closed, then honk onto the ground. When I break

through the forest I come out onto a dirt mining road, and the rumble of

a heavy truck makes the air tremble. Ahead gapes a bleached-white mineshaft

sunk into jagged rock. I clamber up the stony peak and sit awhile on the

sunny top of the world.

Just to my right, perched on a terraced

hillside, is the village Marvin has visited the day before. It's snug and

dainty-looking from a distance; poor as shit up close, according to Marvin.

("This family was eating sweetened flour balls, and the floor was just

dirt.")

High in the boundless blue of the sky,

a pale half-moon hangs suspended (Cosmic Clichés and How to Put

Them to Work for You, p. 198). Marvin had said it that morning, grinning,

raising his face to the sun or sniffing his crumbled eucalyptus leaf: "It's

on days like this you think life mightn't be so bad after all." Speak on,

Learned One. Usually a feeling of just right lasts a moment. But I've climbed

this hills, stopping to meditate whenever I find myself huffing, moving

on with the sweat cooling on my brow and tweed cap clutched in my hand,

and the peace has held and held, filling me with each ungreedy breath.

I follow the mining road down, kicking

pebbles, raising clouds of red grit that cake to my boots. Halfway down,

a dynamite charge explodes with a roar and a bellow, shattering the calm.

A miner ambles over to inspect the devastation of the still-collapsing

rock face. Another group of miners sits under a straw canopy, drinking

tea in the shade. A little further on is an immense ox-pie that some passerby -

or, more likely, the herder himself - has thoughtfully embedded with rocks

so that truck wheels can ride unsullied over it. Propaganda officials will

soon get wind of this selfless action and rush to the scene. It will be

immortalized in a feature film called The Ox-Turd Incident, which will

be shown nationwide, and which everyone will go to see because there is

absolutely nothing else to do in China.

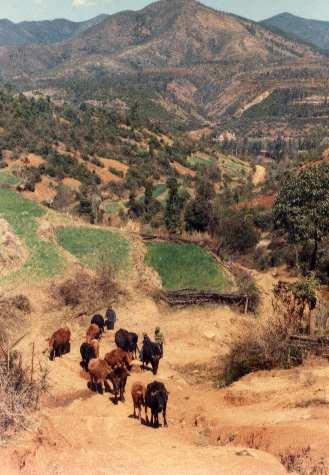

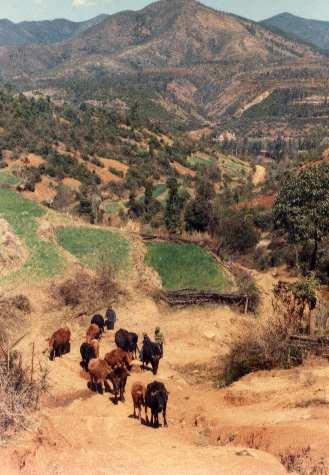

Countryside around Anning (Photo by Adam Jones).

Down, down. Feet getting sore. I have only

the vaguest idea where I am, but like magic the rutted old road takes me

round a last dusty bend - and there is the bridge with the noodle-sellers,

just across from the guest house. Ten minutes after I have my bearings,

I also have my beer. I sit in the cool of the room, gulping Tsingtao and

biting into slim bars of sweet, soul-restoring chocolate.

Marvin arrives back soon after. We sit

wondering where Sjors has gotten to.

"Wonder if he climbed his mountain," Marvin

muses. "Hm. It's funny. You look out your window here and say, 'Oh, there's

a mountain!' - and it takes you a couple of hours to hoof it on up."

He's flattered that I like his stories,

and with the sun fading into the beery haze of late afternoon there's not

much I'd rather do than listen to another one. "A bit different from Nepal,

eh?" I coax him.

"Nepal! Shit, Nepal. You know, it was in

that country that I first saw the road to China. Not China itself, but

the way in. Before they chased us away. You're allowed to go down this

mountain and hang a left" - his hand swoops in illustration. "Well, we went

down the mountain, stowed our gear, and went right. And there we were.

And not long after that, there were people with guns all around us saying,

'Go back, please.'

"Nepal is amazing. You can stand by a creek

bed at ten thousand feet and see this black pebble in the stream. It's

spherical rather than flat, and kind of oily-looking. If you throw it onto

the ground or crack it open with another rock, you find one of these little

fossilized shells the kind with the descending spiral design embedded inside.

And you know that a hell of a long time ago, before the subcontinent came

charging into Asia and pushed up the Himalayas, that ten-thousand-foot

creekbed was at the bottom of the sea! And then you look up, up, like this"

- he raises his arm at an angle well beyond forty-five degrees - "and there's

more mountain, fifteen or eighteen thousand feet more. At the very peak

the air is so thin and cold, you can see little vapour trails streaming

off to form clouds further on. In the blink of an eye you've got ocean-floor

fossils and the highest mountains in the world."

By the time darkness falls, Sjors is back,

feet covered in blisters from his new boots. But he's climbed his mountain.

That evening, over more beer, we find out

he has been a member of the Dutch Communist Party for ten years. "For four

or five years I have been thinking about leaving. But then I look around

at the other parties, and I see it is the best one." He has a mischievous

disregard for the Soviet Union, though, and especially for artistic endeavour

under communist systems. Here in China he's picked up an immense and turgid

tome, one of those endless, drearily-translated revolutionary Chinese epics,

full of blood and steel and superhuman PLA soldiers ("You can keep your

god-damned bribes, this is the People's Liberation Army, do you hear?!")

He sniffs when I ask him what he thinks of it. "Not bad. For socialist

realism."

The next day we're off. We catch the local

bus back to Anning as the sun burns humid tendrils of mist off the river.

In the growing heat of the day we trudge six or seven miles along the country

road to Haikou, a tiny port at the southern tip of Lake Dianchi. Fields

of green mingle with sulphurous industrial plants; chimneys cast a puce-like

pall over the surrounding landscape.

It seems to be PLA convoy day. Dozens upon

dozens of dull khaki trucks, thickly camouflaged, thunder past us on the

narrow road. They are numbered in roughly consecutive fashion, and the

highest number I see is 100.

Any troop movement of this magnitude in

Yunnan likely has something to do with the tense southern border. Indeed,

the China Daily is reporting mounting border violations by the unrecalcitrant

Vietnamese. Every now and then the Viets decide to lob over a few shells

which kill a few cattle and, occasionally, people in nearby communes.

Many of the trucks are dragging dangerous-looking

artillery pieces. There are soldiers in the back, with their Chinese-made

AK-47s. They eye us noncommittally or nudge each other: "Foreigners." I

wave at one truckload for the hell of it, and immediately a dozen hands

shoot up in response, shy grins replacing the blank look of drill-practice.

It makes me feel a little strange. Thirty years ago I might have been facing

those lumpy PLA uniforms in less relaxed circumstances: we Canadians had

shed blood in Korea, too. A little further on we trudge past the convoy

again, stopped for lunch. Hundreds of soldiers lounge placidly or horse

around. This time there are officers in the vicinity, though, and nobody

waves.

Another signpost: Haikou 14 km, by a few

rippling fields and sidelanes where donkeys pull carts and masters along.

It is too far to walk in time for the afternoon boat back to Kunming. So

we flag down the next bus, Kunming-bound. It takes us five or six miles

on to Shangchong, just upriver from Haikou. "How much?" I ask the driver

as we step off. He smiles and shakes his head.

Asia. This mid-morning heat, the buzzing

flies and small children selling bottles of warm, sickly pop outside ramshackle

houses: this isn't China as such, but everything that's homogeneous in

the brown-clodded, colourful continent. We plod the last couple of miles

to Haikou, and I fall behind. Sjors and Marvin have both done their Himalayan

trekking, and know how to keep up a brisk pace. Then - the tinkle of a bicycle

bell, a young man's voice: "Hop on!" I am driven the rest of the bumpy

way by a frail Kunming high-school student who wants to practise his English,

and rattles off his sterling achievements and heartfelt aspirations to

me. He drops me off at the little cubby-hole where boat tickets are sold

and farmers haul squealing piglets aboard the nearby craft. Then my new

friend pedals back through streets redolent with sun-scorched fertilizer

to collect Marvin and Sjors in their turn. I lean against the grimy wall

by the ticket window, returning the stares of the locals, letting Asian

déjà vus carry me away for a while. Maybe there's a cranny

of the globe that's truly a world apart, but I haven't found it, and I'm

not holding my breath.

The boat scuds across the windy surface

of Lake Dianchi. We gaze out the window at the rocky coastline. "Damn,

this looks like Greece," I mumble to Marvin: that stony shore, the bursting

blue of the sky, the richly-hued lake.

A forest fire crawls its way up a hillside

onshore. The passengers crane for a look. The rest of the time they seem

more interesting in indulging the Chinese passion for other people's footwear.

"Where did you get those boots?" asks the

man across from me. He has a shrewd face, and asks searching questions

about capitalism and Yugoslavia before succumbing to his footwear fetish.

"Canada," I reply.

"How much?"

"They were pretty cheap," I assure him.

This is a mistake.

"Ah! Twenty yuan? Thirty?" He strains

his guesses to the very boundaries of the conceivable, knowing something

about the compulsive materialism overseas.

"Um, just over a hundred, actually." This

is two months' wages for many Chinese workers. "But they're good quality,"

I add lamely.

We awake in the cushioned luxury of our

old three-bed room in the Kunming Hotel, regained after a brief haggle.

There is energy to spare as we bustle about our morning business. I'm getting

the day's strolling gear ready when the door slams and Marvin enters, an

aura of calm serenity surrounding him.

"Well, Bruce" - God bless Australasians,

they really will call you 'Bruce' - "Well, Bruce, that was a nine out of

ten, I reckon. For size, shape, smell, slump, texture and gloss."

I make him repeat the categories and I

scribble them down through my giggles. "That's only six!"

"Yeah, but it's scored out of ten," Marvin

continues nonchalantly. "Like, sometimes the slump is so extraordinary

it's worth two. Et cetera."

We are shitting solid again, and all is

well with the world.

XI. Kunming/Shilin/Emei

I know what self-contempt means,

or that torment of conscience which springs from the inability to use the

gifts of Heaven: that is the cruellest of all.

- Diderot, Rameau's Nephew

I don't feel a desperate need to get a traveller's

handle on Kunming. There's something in the sunshine, the ambience, the

way everyone spills onto the street or hunkers down in the somnolent

teahouses. It reminds me my trip is also a holiday. So I prowl the avenues

and backstreets, oblivious to the stares, doing some thinking with a furrowed

brow, stopping when I feel like it to scribble down some epochal thought

I know will seem dumb later.

On the outskirts of town, but before you

hit the periphery of squat housing blocks and factories, the narrow lanes

all seem to flow downhill. The houses wind their way down exactly like

terraced fields, and in the distance the dry, barren, beautiful hills are

outlined with a clarity that hurts the eyes. I retreat to a tiny teahouse,

stuffed into a small pebbled clearing at the end of an alley. I sit and

drink strong green tea and chat with a few of the regulars, my notebook

safely stowed. Many of them are almost classically old: men with long,

worn, elegant pipes which they load with chunks of moist-looking cheroot.

They sit their dusty trousers down on rickety wooden stools, and one of

them tells me - grudgingly, it seems - that he's been doing exactly this, in

this same teahouse, for forty years straight. There are a few younger men

as well. One has brought his young son, who looks shyly at the tea-lady

offering him refills of hot water from the massive, cloth-wrapped kettle.

In the western sector of Kunming there's

a shop selling minority artifacts, and I make my way there, still in no

particular hurry. By the most circuitous route available, in fact. It is

a bland enough department-store affair, with quaint, mass-produced trinkets.

For sale alongside them are the more functional items to which the craftspersons'

skills must be directed by their pragmatic Han supervisors.

But there - there! - under the display glass.

A perfectly marvellous selection of mini hash-pipes! My God, just the thing

to while away those long spring days in Shanghai when we finally make our

big score, from the shady folk in the Muslim quarter who truck in brick-sized

chunks of the stuff from the Western desert.

The symmetry, the artistry! The pipes are

four or five inches long, slim decorated lengths of gleaming brass. They

have not one but two elegant bowls of equal size, equidistant from the

ends.

That throws me for a minute, those two

bowls. But then the magic of their function strikes me. If you were after

a really monstrous buzz, you could load both bowls with the substance of

your choice. If you preferred something milder, you could fill up one only.

Then, the air inhaled through the other bowl would cool the smoke to whatever

extent your fingertip, pressed to the rim of the empty bowl, dictated.

The wondrous simplicity of it all! And

the best part is, the Han Chinese are entirely oblivious to the true purpose

of the little brass masterpieces turned out by the smiling minority artisans.

After all, what else could go in there but ordinary tobacco? I allow myself

an inward chuckle at their exquisite naïveté.

The pipes cost about 75 cents each, Yankee

currency. Hands oily with anticipation, I call the clerk over.

"Please let me see those two trays," I

say.

Slightly disconcerted - you want to see the

entire trays? - she pulls them out for my inspection. All is as I expected,

though I'm darned if I can find the hole in the mouthpiece for drawing

through the smoke.

I look a little longer, a little closer.

Realization dawns.

I blush up at the clerk. "Door handles?"

"Door handles," she confirms - what else?

I wander along, skirting the large park

in the north of Kunming where wrinkled men sit at stone tables, mumbling

over cards. I'm thinking of Kerouac, my face turned now and then to the

sun. Thinking especially of that astounding passage early in On the Road

where Sal Paradise rhapsodizes: "... the only people for me are the mad

ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous

of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace

thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding

like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centrelight

pop and everybody goes 'Awww!'" Thinking about how slothful, how unimaginative

I am, how often; how meagre and indecisive is my art. About how marvellous

and terrible it would be to live like Dean Moriarty, Kerouac's hero: to

burn down so far you burn out even the capacity to communicate your visions.

...

Less scrupulous writers than your servant might fabricate a lead-in like that, to slide you smoothly into

the preposterous episode they're about to relate. "I was intently pondering

this mysticism that pervades all Aquinas's writings, when who should I

see down the path but the erstwhile Samuel Grimsby, Professor of Medieval

Literature at King's College, Cambridge ..." But this is fairdinkum, Kerouac

is on my mind and anxiety in my heart, when at my elbow a voice says, "Excuse

me, sorr."

Oh no. Oh, Jesus.

"Please let me introduce myself. I am a

student at Kunming Teacher's College, majoring in English. Where please

are you from?"

I scream inwardly. But he gets an answer.

"Oh! Canada. Oh. Are you presently going

to visit the temple near here?"

"No," I reply more firmly. "I'm walking

back to my hotel." Take the hint.

"Oh, walking. I like walking. It is - good

exercise! Which hotel?"

But I can't believe he likes anything.

His voice is sullen and vapid and empty, not a breath of the usual I-study-English

chirpiness which would be irritating, but at least familiar. If a piece

of driftwood stranded on a flotsam-littered shore could speak, it would

be with a voice like his. The face holds no surprises sunken, dark, lifeless.

Lifeless.

"Ah, the Kunming Fandian. So you are passing

your vacation in China."

"No, I'm studying in Shanghai," God damn

it! He looks at me, puzzled - I don't seem to be studying; I seem to be vacationing

in Kunming. Which, in fact, I am. But he lets it slide.

"Would you object if I accompaniment you."

There is only a marginal difference in intonation when Driftwood asks a

question. "I would like to practise my English."

I turn to him and say politely, "As a matter

of fact, I would. You see, I have been meeting many people recently who

only want to practise their English. I find it very dull."

"Ah. You are - 'tired of it.'"

I smile with grateful relief. "Yes. I'm

sorry. You understand - I would just like to walk by myself for a while."

In the drowsy heat of the day, with grandmothers on tiny bamboo chairs

in secret doorways.

He nods, and I walk on.

He keeps pace. "Your country is very lucky.

It has many forests. From those forests you may extract wood pulp and from

mountain rivers get hydroelectric power - electricity."

I look at him and say with considerable

restraint, "You don't need to practise your English. It is very good."

"Thank you. Also you have many planes."

"What?"

"Many plains. Where you grow weed."

"Oh. Oh, crumbs." I quicken my step. Driftwood

follows along, a level above me on the raised sidewalk. There is a milling

market crowd ahead. Maybe -

"Maple leaf trees," Driftwood interjects

suddenly.

"Yes."

"You also have maple leaf trees and the

maple leaf is on your flag. Every autumn the country is full of maple leaf

flags."

I stare resolutely at my boots. It makes

me less likely to try to bite his eyes out.

"From the trees you extract sugar. Maple

sugar." In his rote incantation, his voice has become nearly toneless.

"How do you know all this?"

Glumly: "I read books."

We walk on. Rather, I walk off, or attempt

to. He sticks doggedly to the sidewalk. I don't see him whenever he zeroes

in: my boots are altogether too fascinating.

"Excuse me. What job do you want to do

when you have graduated."

I say hopelessly, "I don't know."

"Oh. I want to be an English teacher - a

qualified English teacher." He waits for my approval, walking beside me

on the road now. I notice that he comes up to my shoulder, and the way

he carries himself makes him seem even smaller. Grudgingly I ask, "How

old are you?"

"Thirty. Certainly older than you." He

is content with that. "Do you know the Chinese characters on the sign?"

My question has perked him up in a vague sort of way: Now we're rolling!

And now his inquiries are more than statements.

I know three of four.

"I am very impressed with your master of

Chinese," he says dutifully. "After only three months."

"Six in China, actually," I shoot back

spitefully. "Plus a year in Canada."

"Oh. Excuse me, do you know why these houses

all have mirrors above the doors?"

I look up. The houses all have mirrors

above the doors. "Why?"

"It is a Chinese superstition. No! A Kunming

superstition!" He laughs with awful hollow jocularity. "They think if the

mirrors are there they will keep away - evvil."

"Devil?"

"Evil."

"Oh."

And then, a couple of minutes later, he

gives up. "I go then."

I feel a mild pang. "Yes. Look, I'm sorry.

I just don't want to -"

"I know. Goodbye." He shakes my hand. Empty

eyes.

I cross the street to buy a notebook. A

minute later there comes a sullen tap on my shoulder. Driftwood. "You will

find a better selection over there," he says, pointing at a large shop.

And then he is gone.

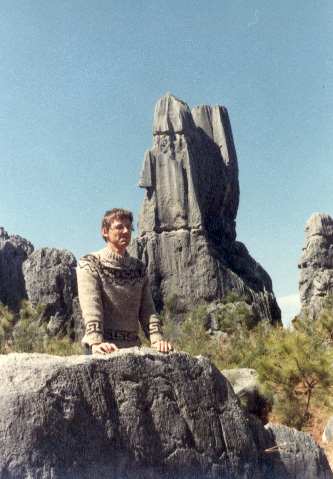

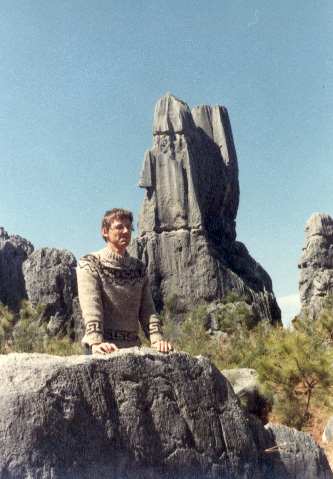

Sjors in the Stone Forest (Shilin)(Photo by Adam Jones).

I split my time in Kunming with the obligatory

side trip to the famous (and hence hectically-touristed) Stone Forest:

Shilin, three hours way by bus. Marvin, Sjors and I share a room there

with an Alaskan, Richard - huskily-built and with an impossibly luxuriant

beard that has me rubbing the carefully-nurtured scruff on my face self-consciously.

("Don't worry, mate," Marvin chips in. "Before he went to Alaska his was

probably just like yours.")

Richard likes to view the hundreds of bizarrely-eroded

stone pillars by eerie moonlight. After a bottle of Chinese vodka, he orders

us out into the bright silhouette-laden night. We clamber over boulders,

through caves carved into or between the pillars, over miniature precipices,

until we reach a vantage point and stand there, breathing heavily. The

forest lies below, jagged and silent. Marvin tries to take a photo with

the available light, but his prognosis is pessimistic. Then we follow the

road that links the small villages in the area. It returns us to the little

town, now all but deserted of tourists.

Vodka and moonlight flow through my system.

I think I feel From the void we come; through emptiness we pass to nothingness.

I repeat it like a mantra, hoofing along the rocky path, well behind the

others. I fiddle with the mantra's syntax. Sweet despair fills me to the

brim. I want to sit down on one of those boulders and write - something to Lindsey, with the lunar glow lighting my page. But the only

suitable medium seems to be poetry. And haven't I already tried to write that

poem?

Dark - I breathe, and feel the

pinprick glow

Of icy fibre, taut as life

The desert chill. When empty, I am

full.

When full, your touch unsettles.

Life trembles, giddy as

A starhaze flicker.

Besides, I can't see any way of working "void,"

"emptiness," "love" and all the rest into verse without sounding like Sartre

after at least one bottle too many. I go back to the hotel and sleep.

Looking beyond Kunming, I realize I have

a problem.

Question: What's the one thing a weary

student vows not to think about during his break?

But school and Shanghai are still there,

and will loom ever more insistently from now on. Winter holidays are officially

over. Classes for foreign students won't be underway, I know, for another

week or so - none of us is that dedicated. But most everyone will be back

and in a studious frame of mind by the 20th, which is four days away. At

that point questions will be asked about my absence, and it's a matter

of gauging the point at which irritation turns to anger or punishment.

I have no intention of getting back before

the end of the month. But even that gives me just two weeks - and here I

am in Kunming, at the farthest point of my travels, Shanghai a thousand

miles and a world away. Ahead, to the north, lies the Sacred Mountain:

Emei Shan. Beyond that is Chengdu - and Chongqing, nestled in southeast Sichuan

Province at the confluence of the Yangtze and Jialing rivers. From Chongqing

the Yangtze Gorges cruise is unavoidable. I can take the boat all the way

to Wuhan, China's "Big Red Steeltown." But Wuhan to Shanghai by boat is

another four days, which sounds a tad excruciating: I'm running low on

reading matter. What's more, all train routes from Wuhan take huge detours

north (to connect with the Shanghai-Urumqi line), or southwest to Changsha

in Hunan Province; only then do they deign to move east to Shanghai.

Two weeks.

Hmmmm.

I can shave a bit here and there. From

Emei Town, base camp for those attempting the ascent of Emei, three or

four hours short of Chengdu, a bus runs to Leshan a few miles away. Another

rattles on to Neijiang which is a stop on the Chengdu-Chongqing rail line.

That would cut out Chengdu, whose spicy dofu could wait for summer travels.

And glancing at the map, I see there's no need to take the Yangtze boat

all the way to Wuhan. At the bottom of the loop which the river takes after

Shashi - after the Gorges - lies the town of Yueyang, halfway down the Wuhan-Changsha

line. Bye-bye, Wuhan, and good riddance.

But it's still pushing it. What nags is

four days: the time required to jog up the Sacred Mountain and back down

again. But the only alternative to the rail journey north is to head straight

east from Kunming - through the heartland of the south, to be sure, but retracing

my steps as far as Guiyang, and there doesn't seem to be much of interest

between Kunming and Changsha. It would be redundant and aesthetically displeasing:

a crooked crescent instead of a nice wide loop. But I could hardly go through

Emei Town - could hardly stop there, which would be necessary in order to

lop Chengdu off the itinerary with a cross-country bus ride - without climbing

the Sacred Mountain.

Could I?

I mean, everybody climbs Emei Shan. I've

even decided to call this section of the book "The Sacred Mountain." A

couple of pages of dazzling descriptions of the view from the peak; the

usual references to the pilgrims so inspired by the sight that they leap

into the magical sunrise to their deaths ... a couple of pages and I could

take it easy for the rest of the trip, the climax behind me, running downhill

in more ways that one. There's simply no way around it. If I pass through

Emei, I have to skiffle on up the mountain.

I decide to pass through Emei and give

the mountain a miss.

Once I make the decision I feel good about

it. My mind thrums like an efficiently functioning machine, a bothersome

glob of detritus wiped from its works. One look at the grey skies of Sichuan

Province, when I pull myself to the train window, adds to my new conviction.

"Look, ahead," Sjors says ironically, Marvin

still asleep in his bunk ("Piss off, I'm a late riser"). He points to the

sky. "This must be the border between Yunnan and Sichuan!" Brilliant morning

blue is fleeing before the advance of ugly brown tufts of cloud. Ahead

lies impenetrable grey.

I smirk. We'd actually passed the border

during the night, at a point along the stalactite of Sichuan which pushes

it way far south into Yunnan Province. But I say a sad, silent farewell

anyway to lovely Yunnan, which has reddened my forearms and peeled my sensitive

nose so delightfully. It is time for The Real China again.

The guidebook burbles that the Kunming-Chengdu

ride is one of the most beautiful in China. There are, it's true, deep

vistas of mountain; blunt valleys choked with fertile sediment; winter-shrivelled

rivers hundreds of feet below. There are also about eight thousand tunnels.

You have about four seconds to enjoy each moderately attractive view before

the next tunnel cuts it off with a leaden whoosh. Marvin, finally roused,

joins me at the Walkman, plugging in a spare pair of earphones, and we

spent an hour listening to top-volume Stones. We chew the remnants of bread

and cheese purchased in Kunming, look out the window, tap our feet with

mounting frustration and eventually go back to sleep. We awake for Emei

Town. Sjors, who has sat implacably by the window for the duration, says,

"You missed some nice scenery."

The train chugs to a halt and we dismount.

Outside, some chic Hong Kong Chinese are taking a giggly picture under

the station signpost for Emei. We watch the obsessive shutterbugs with

horror. Marvin blurts out, "Here we are, 'Me at Emei'. Christ, what was

the first picture ever taken of them? 'Me Coming Out of My Dad's Dick'?"

We see Emei, walking, hunting for a hotel,

and pronounce Pythonesque judgment on it: "This is not a town for visiting.

This is a town for laying down and avoiding." It is a main street. Perhaps

no more drab than a dozen other Chinese small towns I've seen. But this

one comes after Yunnan and colour and sunshine. I blink. "Ouch."

I don't want to linger. Marvin and Sjors

are bickering energetically over routes up the mountain, and they glance

up with the odd look: "You sure you don't want to come with us?" But I've

burned my bridge; now I have to lie in it. We have one last raveup dinner

too much beer, and spices that leave us breathless and the next morning

I say goodbye to the two of them.

"It's been a real pleasure trucking with

you guys," I stammer. Awkwardly. Because what do you say to people you've

lived with and bitched to and drunk with and lent money to and burdened

with your life story, over a week-and-a-half on the road? Fine, fine people.

May their journeys treat them kindly.

XII. Leshan/Chengdu

Then it's the morning bus east to Leshan.

An hour's drive through numb countryside. I feel that familiar weighed-down

sensation, staring through the dirt-streaked windows as we leave Emei.

There is a store on the outskirts with a sign, in English, as dull and

clumsy as the town itself. THE SHOP OF THE THINGS, it reads.

I've been describing the skies of China's

February as grey, endlessly grey, but that isn't quite right. Three-quarters

of any rural view is simply blank. The eye searches in vain for some definition

in the heavens, some outline of cloud, some vague tint. Nothing. The Chinese

sky seeps into the earth on days like this, it is foggy enough that the

delineation between the two genuinely blurs; it envelops the dreary, formless

houses, makes a bustling, animated market scene look worn and bone-weary.

I think: if that sky can drag my soul down in a month of travelling (a

month of motion, of contrast), what must it do to someone born under it,

descended from people who've lived and toiled under it for millennia, who

could almost pass it on in their genes? What must it be to turn your eyes

to heaven, and for months on end every year see nothing but void?

I remember a passage in a book I've been

plowing through in fits and starts on the trip: Suzuki's enigmatic selected

writings, Zen Buddhism. Suzuki speaks of the transformation Buddhism underwent

when it made its way into the Chinese heartland from the flourishing Indian

subcontinent. He jumps from there to compare the two peoples, the two minds,

the two souls. Zen, he argues, is "a most natural product of the Chinese

soil":

... the Chinese are above all

a most practical people, while the Indians are visionary and highly speculative.

We cannot perhaps just the Chinese as unimaginative and lacking in the

dramatic sense, but when they are compared with the inhabitants of the

Buddha's native land they look so grey, so sombre.

The geographical features of each

country are singularly reflected in the people. The tropical luxuriance

of imagination so strikingly contrasts with the wintry dreariness of common

practicalness. The Indians are subtle in analysis and dazzling in poetic

flight; the Chinese are children of earthly life, they plod, they never

soar away in the air. Their daily life consists in tilling the soil, gathering

dry leaves, drawing water, buying and selling, being filial, observing

social duties, and developing the most elaborate system of etiquette.

Hence the methodical Chinese obsession with

painstaking historical records - the need to carve deeds into stone, to etch

them against the ages.

When Buddhism with all its characteristically

Indian dialectics and imageries was first introduced into China, it must

have staggered the Chinese mind. Look at its gods with many heads and arms

something that has never entered into their heads, in fact into no other

nation's than the Indian's. Think of the wealth of symbolism with which

every being in Buddhist literature seems to be endowed. The mathematical

conception of infinities, the Bodhisattva's plan of world-salvation, the

wonderful stage-setting before the Buddha begins his sermons, not only

in their general outlines but in their details bold, yet accurate, soaring

in flight, yet sure of every step these and many other features must have

been things of wonderment to the practical and earth-plodding people of

China.

"Earth-plodders. Yeah, I like that." Marvin

had been searching for a way to articulate what rankled him about China,

what nagged him to compare this country with the India where he'd passed

seven months. This sky, and Suzuki's words on the wintry Way of Zen "When

hungry, I eat; when tired, I sleep," says the master matter-of-factly seems

to explain a lot. I think of those magnificent Sung and Ming Dynasty landscape

watercolours. You have to look a long time before you see that the clouds

enveloping those craggy peaks are not painted on, but simply left blank;

that the vast lake over which the helmsman steers his tiny boat is just

emptiness. The Chinese had spent over two thousand years paring down life

and thought to their unfathomable essentials, and when all was stripped

away they found only nothingness remained. And so they gave it supreme

meaning. Impenetrable, like that sky.

It takes, as it turns out, a scant 36

hours for my careful plans to be derailed.

"The road to Neijiang is closed to foreigners,"

the lady behind the Leshan ticket counter tells me. I've stowed my bags

and booked a room just up from the station: all set for some sightseeing

today and the onward bus tomorrow.

No go.

"Look, I don't want to go to Neijiang.

I want to go to Chongqing. Neijiang just happens to be where I can pick

up the train. I don't want to spend the night there. Look, I'll keep my

eyes closed the whole time."

She is unimpressed by my feeble attempt

at humour. "I'm sorry. You have to take the bus straight through to Chongqing."

I pause. "There's a bus to Chongqing?"

"Yes!"

"And you can sell me a ticket?"

"Next window."

There is no-one in line at the next window.

"I'd like to buy a ticket to Chongqing," I announce confidently.

"We cannot sell you a ticket to Chongqing."

"Are you telling me there's no bus?"

"That's right."

I leap on it. "But your partner said there

was a bus."

Blushes and embarrassed chatter all round.

Much face lost. "Foreigners are not allowed to take the bus. You must go

to Chengdu, then take the train." Which is exactly what I've come to Leshan

to avoid.

"God damn it," I say, nodding agreeably.

They smile back, relieved.

I set an emphatic pace to the police station,

which fortunately is far enough away to give me time to cool off. On the

way, I decide I rather like Leshan. It is bigger than I expected, and full

of late-morning bustle.

I spend a good hour with the good people

of Chinese Public Security. "Look, it's crazy that I should have to go

all the way north just to catch a train going south. Why the trouble? Why

can't I just hope a bus to Neijiang?"

"It's off-limits. Regulations," shrugs

the boyish, crew-cut cop apologetically. The Foreign Affairs Office has

a staff of about five, and I strongly suspect I'm their first visitor for

a while. One of them is female and very dark-eyed pretty, which detracts

somewhat from the force of my argument.

"Well, to Chongqing then."

"But the whole road is closed, not just

Neijiang. And besides, the bus to Chongqing takes two days - very slow, and

passengers spend the night in Neijiang, which is -"

"Off-limits to foreigners. So I have to

go all the way to Chengdu."

"There's a bus at one in the afternoon,"

the cop says, deferentially but with finality. "You'll be in Chengdu by

five or so, and you can catch the evening train to Chongqing."

I puff intently on a cigarette, dragging

out the drama as long as I can. "Will you call my hotel here and explain

the situation, and ask them to refund the money I've paid for my room?"

Saving face is a custom not limited to

orientals.

"No problem. No problem at all," says Crewcut,

and he leaves the office. I turn to the pretty girl and say, "While I'm

here, will you give me a permit for Yueyang and Shaoshan?"

Everyone grins in a friendly sort of way.

The foreigner isn't going to be a bad sport after all! The permit is finished

and stamped in record time. Crewcut returns with a businesslike expression

that tells me all is arranged, and I head out for a cheap and tasty noodle

lunch across the street: a team of proprietors fusses over me and chats

solicitously; they beam when I order another serving.

Somewhere nearby is Dafu: Leshan's Big

Buddha, the largest stone carving in China. Twelve hundred years old, or

thereabouts. But I have a bus to catch.

Six hours of bone-jarring country road

later and I am wandering up a gracious, tree-lined avenue in Chengdu, my

head pounding from the bus driver's World War Two-issue air-raid siren.

That's all I see of Chengdu. I have to stand crumpled up against the roof

on the crowded bus to the train station, where I continue gathering data

for my Master's thesis on Scalp Conditions in New China. From occasional

glimpses out the window, Chengdu looks spacious. They are building an impressive

new station complex, complete with escalators; meanwhile, wayfarers are

shunted to chilly benches outside the construction site. I find my train,

pay extra for a sleeper, play idly with a presumptuous little urchin in

the opposite berth who invites me to his house in Chongqing to continue

the fun and games. By the time I realize how exhausted I am, I'm asleep.

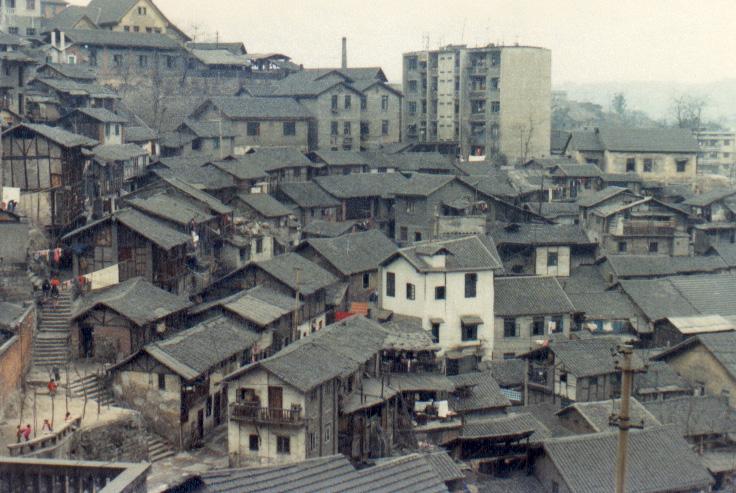

I wake to grating loudspeakers as the train moves through the tangled,