A Port-au-Prince Journal

Text and photos by Adam Jones

A Port-au-Prince Journal

Text and photos by Adam Jones

Note: This journal covers impressions, encounters, and experiences from three weeks spent in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in December 2001 and January 2002. Side trips to Pétionville, Kenscoff, and the coastal town of Jacmel are also featured. As well, my travelling companion, Miriam Tratt, and I visited Haiti's north coast, in and around Cap-Haïtien. This is covered separately in "A Taste of Paradise in Haiti (Yes, Haiti)", elsewhere on this site.

Larger versions of most of the photographs accompanying the text, and many others besides, can be found in the Haiti Photo Galleries.

Nothing is ever explained. Nothing ever makes sense. Nobody wants to search for the answer. You will never, ever learn the truth. If you apply the standards that you and I have been raised with, it's not going to work here.- North American social worker in Port-au-Prince

"If you hear what sounds like gunshots tonight, don't worry," says Sister Ellen. "It's only fireworks." It's that time of year, after all -- four days after Christmas, with New Year's Day -- which coincides with Haitian independence celebrations -- just ahead. But the gunfire reference is hardly out of place. Barely a week-and-a-half ago, Haiti experienced its second attempted coup of 2001: a strange and half-baked affair, in which alleged former members of the country's military tried to storm the National Palace in downtown Port-au-Prince. The assault was beaten back by paramilitary forces loyal to the president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, and quickly fizzled, with the apparent leader of the assault -- Guy Philippe, a former military man also accused of complicity in the coup attempt a few months earlier -- fleeing to the Dominican Republic. But it was a deadly serious affair for the handful of attackers and defenders who lost their lives, and in its wake, rumours swirled. The political opposition, which has been locked in protracted conflict with the Aristide government over disputed 2000 election results, accused the president of having staged the "coup" attempt himself to discredit his opponents. The charges are most commonly aired by those long convinced that Aristide is the incarnation of radicalism and social evil;(1) but even some more moderate commentators consider the likeliest explanation to lie in internecine struggles among members of Aristide's fractious Lavalas "Family."(2) Whatever the truth, the they further fuelled the paranoia of a country that Sister Ellen described as "a ticking time bomb." It seemed possible that Haiti, the poorest country in the western hemisphere -- on a par with Chad and Bangladesh, with an average annual income of US $250 per family -- had yet to hit rock bottom; and the history of the place suggested that, when it did, the crash would be bloody.

Sister Ellen is a Catholic nun who has lived and worked in Haiti for well over a decade, and -- together with a couple of equally dedicated religious, and a handful of

Haitian assistants -- runs the Hospice St. Joseph. We arrive on its doorstep after a brisk flight from Miami International Airport, where we had been the only white faces

in the waiting lounge for Port-au-Prince -- a stark, almost apartheid-style contrast with the adjoining lounge, which was full of nothing but white faces, bound for holidays

in Cancun. Our interest in the hospice, apart from the rave review given it by our Lonely Planet guide, lies in its human-rights-related work: "Since its founding," reads the

promotional pamphlet for St. Joseph, "the staff … has been dedicated to walking in solidarity with the poor. We endeavour to call the attention of visitors to the many

injustices put on the backs of the Haitian people, while encouraging our guests, who will return to their own countries, to help us work toward alleviating these injustices."

It also runs a small clinic to "assist people needing surgery or hospitalization," and those "who require advanced surgery or medical treatment in the U.S."; a food program

for malnourished children; a small commerce program for women; and a school-sponsorship program that helped poor Haitian students complete elementary or high-school studies. All in all, it seems the sort of place that does more good work in a day than I have managed in 38 years.

Sister Ellen is a Catholic nun who has lived and worked in Haiti for well over a decade, and -- together with a couple of equally dedicated religious, and a handful of

Haitian assistants -- runs the Hospice St. Joseph. We arrive on its doorstep after a brisk flight from Miami International Airport, where we had been the only white faces

in the waiting lounge for Port-au-Prince -- a stark, almost apartheid-style contrast with the adjoining lounge, which was full of nothing but white faces, bound for holidays

in Cancun. Our interest in the hospice, apart from the rave review given it by our Lonely Planet guide, lies in its human-rights-related work: "Since its founding," reads the

promotional pamphlet for St. Joseph, "the staff … has been dedicated to walking in solidarity with the poor. We endeavour to call the attention of visitors to the many

injustices put on the backs of the Haitian people, while encouraging our guests, who will return to their own countries, to help us work toward alleviating these injustices."

It also runs a small clinic to "assist people needing surgery or hospitalization," and those "who require advanced surgery or medical treatment in the U.S."; a food program

for malnourished children; a small commerce program for women; and a school-sponsorship program that helped poor Haitian students complete elementary or high-school studies. All in all, it seems the sort of place that does more good work in a day than I have managed in 38 years.

There is room for us, just barely, at the inn; and we gratefully settle in to one of the "clean, sweet-smelling rooms" Lonely Planet had promised us, and shower away the accumulated grime of 24 hours spent in airplanes and sprawled out on airport carpets.

My companion for this adventure is Miriam, a former girlfriend and enduring compañera who last traveled with me to Moscow in 1997 for research on the final case-study of my Ph.D. dissertation, on the post-Soviet Russian press. She is a first-rate research assistant who happens to speak fluent French, which I anticipate will come in

handy in Haiti, even though 90 percent of the population speaks only Creole. And she has the hardiness and spunk that was required to trundle around Moscow for a

month and will likely be even more valuable in Haiti: when I called her, with some trepidation, to ask whether she had heard of the attemped coup (and, by implication,

whether she was still willing to accompany me), she responded blithely: "Yeah. But it doesn't sound like a very serious attempted coup." As an example of

sangfroid, this was surpassed only by my mother's reaction: "If they have any more coups while you're down there, you should get in touch with The Globe and Mail

and see if they'd be interested in running a couple of stories by you."

My companion for this adventure is Miriam, a former girlfriend and enduring compañera who last traveled with me to Moscow in 1997 for research on the final case-study of my Ph.D. dissertation, on the post-Soviet Russian press. She is a first-rate research assistant who happens to speak fluent French, which I anticipate will come in

handy in Haiti, even though 90 percent of the population speaks only Creole. And she has the hardiness and spunk that was required to trundle around Moscow for a

month and will likely be even more valuable in Haiti: when I called her, with some trepidation, to ask whether she had heard of the attemped coup (and, by implication,

whether she was still willing to accompany me), she responded blithely: "Yeah. But it doesn't sound like a very serious attempted coup." As an example of

sangfroid, this was surpassed only by my mother's reaction: "If they have any more coups while you're down there, you should get in touch with The Globe and Mail

and see if they'd be interested in running a couple of stories by you."

But what were we doing going to Haiti? The question had been posed by various friends, especially in the wake of the failed coup. One pal, no stranger to Third World misery himself, said he'd heard that Haiti was "the most depressing place on earth." Others still seemed to perceive it as the land of voudou and the Tontons Macoutes, the paramilitary thugs whom the Duvalier family dictatorship had used to fend off threats both from the civilian population and the official armed forces.

I had no ready answer to their inquiry. Part of the explanation perhaps lay in the fact that whenever I heard someone say, "Why would you ever want to go there?," I took it as a personal challenge and inspiration, one that had led me to some of the great traveling experiences of my life (Colombia, Nicaragua, South Africa). I wasn't put off, in other words, by dismal reputations. In a more proximate sense, I had rustled up a little funding for a research project on human rights in Latin America, with a particular focus on the phenomenon of paramilitarism. In Haiti that seemed to be a relic of the past, thanks to the arrival of something resembling democracy and the dissolution of the Haitian armed forces in the mid-1990s. This suggested that an outside investigator was probably less likely to run afoul of certain dark interests, and end up trussed, tortured, and mutilated in a ditch somewhere. (I'd originally planned a return visit to Colombia, but was talked out of it by nervous authorities at my institution in Mexico City -- and probably for the best, given the paramilitary reign of terror there.)

But there was no denying that I was starting more or less from scratch. To the extent that I knew anything serious about Haiti, what captivated me was the old cliché of the "land of contrasts." What was once the world's richest colony, "producing three-quarters of the world's sugar by 1789, [and] also leading the world in production of coffee, cotton, indigo, and rum,"(3) was now a veritable byword for destitution. A land that was once densely forested had been turned into one of the world's most infamous cases of environmental despoliation and erosion, leaving only a tiny fraction of the original forest cover still intact, and hundreds of square kilometers in which denuded hills and deeply-etched gullies testified to the catastrophic effects of poor people's endless search for charcoal to cook their meager meals with. The world's first black republic, and the first country anywhere to abolish slavery, was scarcely less "racially" divided today -- though the divisions this time were between blacks and mulattoes.

We are presented to an ebullient group of visiting Americans, mostly midwestern, mostly young, and one of them on her first trip to a Third World country (as, come to think of it, is Miriam). As a few of us sip from cold bottles of the excellent Haitian beer, Prestige -- isn't it remarkable how many

brutally poor countries produce world-class alcoholic beverages? -- Sister Ellen fills us in on recent political developments, and on the activities of the hospice. She also

has some hair-raising tales from the period following the coup that overthrew President Aristide in 1991. The hospice became a place of refuge for Haitians who feared

for their lives with the Army back in power -- "First only men, then entire families" -- and ended up housing perhaps a dozen of them at a time. "We were all wondering

whether the Army would have the nerve to break into a place owned and managed by Americans, and in the end they didn't. But they used to drive by very early in the

morning, say at 4 o'clock, and fire their guns into the air."

We are presented to an ebullient group of visiting Americans, mostly midwestern, mostly young, and one of them on her first trip to a Third World country (as, come to think of it, is Miriam). As a few of us sip from cold bottles of the excellent Haitian beer, Prestige -- isn't it remarkable how many

brutally poor countries produce world-class alcoholic beverages? -- Sister Ellen fills us in on recent political developments, and on the activities of the hospice. She also

has some hair-raising tales from the period following the coup that overthrew President Aristide in 1991. The hospice became a place of refuge for Haitians who feared

for their lives with the Army back in power -- "First only men, then entire families" -- and ended up housing perhaps a dozen of them at a time. "We were all wondering

whether the Army would have the nerve to break into a place owned and managed by Americans, and in the end they didn't. But they used to drive by very early in the

morning, say at 4 o'clock, and fire their guns into the air."

Dinner, Sister Ellen informs us, will be at 5:30, and it is important that everyone not only be on time, but be duly appreciative of the food laid before them; waste is always tacky, but in an impoverished land like Haiti it is downright offensive. We are given an overview of the electrical-power situation, which I suspect is one of the more time-honoured topics of conversation in Port-au-Prince. The municipal electrical authority distributes its precious current erratically and unpredictably, and the result is 12 hours or more a day without city-supplied power. To compensate, the Hospice Saint Joseph has its own solar-powered generator on the roof, but there is not much that can be done about the thin stream of water that is all I can tease from the shower-head in my bathroom. Water, too, is precious … and hazardous. We are encouraged to drink only bottled water (the local brand has the curiously Celtic name of Culligan's), and to use it for brushing our teeth as well. I almost never follow the latter advice -- I have been brushing with notorious Mexico City water for the past two years, without unhappy incident. But something tells me to abide by the injunctions this time. I have seen that water flowing in murky rivulets along the streets outside our gates, and it counsels caution.

In the afternoon, we take a first walk around the neighbourhood of Christ Roi. It is an immediate and churning assault on the senses: the suffocating mid-day heat; the packed streets, with women vendors straddling almost every metre of sidewalk, bantering and haggling, while purposeful-seeming strollers and bleating vehicles weave in and out and around; the half-starved-looking men hauling carts up steep backstreets, shirtless, every sinew straining; the sickeningly sweet aroma of rotting fruit mingled with a rancid undertone of urine and raw flyblown meat ... Toto, we are definitely no longer in Kansas. It is all fascinating from the first, and friendly, once we get into the swing of bidding a singsong "Bonjou" to every last passerby.

We haul ourselves back to the hostel in time for dinner, gathering as a group, a prayer and a spiritual song in Creole before we load up our plates with tasty vegetarian dishes. The proceedings are enlivened by animated chatter, and we wash and dry our own plates and cutlery afterwards. Self-help begins at home. In the evening, Miriam attends a mass on the verandah, and emerges to tell me that she feels spiritually renewed. I have spent the interim in my room, passed out on the bed, and feel similarly refreshed; when Miriam calls it a night, I cart the laptop we have brought to Sister Ellen's administration desk. I spend the last couple of hours of the evening writing these thoughts and impressions, while cicadas hum, little gecko lizards make their odd guttural clicking noises, the smell of burning charcoal and stale piss wafts up to the balcony, and distant, boisterous music resonates in the humid night.

The next morning I will rev up the laptop to find that the file has been almost totally corrupted, and is irrecoverable save for fragments of the first paragraph and the last. I leave it to the reader to decide whether there is a metaphor relevant to Haiti here, but after uttering a few words under my breath that are probably rarely heard in this religious household, I decide to take a lesson from the Haitians I have wandered among in the first two days of the trip. I pick myself up by the bootstraps and start again.

Tourist, don't take my picture

Don't take my picture, tourist

I'm too ugly

I'm too dirty

I'm too skinny

My donkey is overloaded

My house is made of straw …

Your camera isn't used to such things, tourist.

- Poem (translated from the Creole) by Haitian writer Felix Morisseau-Leroy

No Electricity -- No Security -- No Water -- Lots of Garbage -- Lots of Mosquitoes -- What the HELL am I doing Here!!!!

- Sticker seen in Port-au-Prince

On our first full day in Port-au-Prince, all but one of the new arrivals departs for the interior. They leave behind Frank, my roommate, who will be catching a flight to

Pignon in the eastern highlands the following day. When we mention that we are planning to tour around downtown, he asks if he might tag along. We gladly accept, and

after a false start out of the gate and a bit of head-scratching, we find our way down to Avenue John Brown. It is one of the capital's major arteries, linking downtown

with the wealthy hilltop suburb of Pétionville. We stroll along it, dodging the various street-stalls, manholes without covers (with cesspools and rubbish tips within), and

oncoming traffic. The day is hot but tolerable, with a slight sea-breeze blowing. After half an hour or so, we spy the landmark we've been looking for: the National

Palace, a "three-domed, pristinely white building [which] was completed in 1918 and modeled on the White House in Washington, DC" (Lonely Planet, p. 361). Most

recently, of course, it was the venue for the aborted coup attempt of December 2001. Although the palace is officially closed to visitors, today the front lawn is filled with

an incongruous crowd of ordinary Haitians -- though the gates remain locked, and even vendors seeking to sell soft drinks to those inside are shooed away by armed

guards. What's going on? According to a friendly young Haitian man chewing on a stalk of sugar cane, it's all a matter of preparations for the Independence Day

celebrations on January 1st, though what role the occupants will play in them can only be guessed at. Frank leans through the iron fence to photograph one group of

young people who are smiling and gesturing to us. But as soon as two of the young women in the group spy Frank's camera, they yelp with laughter and in rapid

succession leap to their feet, turn their backs to us, and bend themselves double -- giving us a good view of their bums, clothed of course. A good-humoured camera

shyness is conveyed.

On our first full day in Port-au-Prince, all but one of the new arrivals departs for the interior. They leave behind Frank, my roommate, who will be catching a flight to

Pignon in the eastern highlands the following day. When we mention that we are planning to tour around downtown, he asks if he might tag along. We gladly accept, and

after a false start out of the gate and a bit of head-scratching, we find our way down to Avenue John Brown. It is one of the capital's major arteries, linking downtown

with the wealthy hilltop suburb of Pétionville. We stroll along it, dodging the various street-stalls, manholes without covers (with cesspools and rubbish tips within), and

oncoming traffic. The day is hot but tolerable, with a slight sea-breeze blowing. After half an hour or so, we spy the landmark we've been looking for: the National

Palace, a "three-domed, pristinely white building [which] was completed in 1918 and modeled on the White House in Washington, DC" (Lonely Planet, p. 361). Most

recently, of course, it was the venue for the aborted coup attempt of December 2001. Although the palace is officially closed to visitors, today the front lawn is filled with

an incongruous crowd of ordinary Haitians -- though the gates remain locked, and even vendors seeking to sell soft drinks to those inside are shooed away by armed

guards. What's going on? According to a friendly young Haitian man chewing on a stalk of sugar cane, it's all a matter of preparations for the Independence Day

celebrations on January 1st, though what role the occupants will play in them can only be guessed at. Frank leans through the iron fence to photograph one group of

young people who are smiling and gesturing to us. But as soon as two of the young women in the group spy Frank's camera, they yelp with laughter and in rapid

succession leap to their feet, turn their backs to us, and bend themselves double -- giving us a good view of their bums, clothed of course. A good-humoured camera

shyness is conveyed.

The friendly young man standing with us outside the fence tells us he is poised for a return flight to Montreal, where he lives -- part of the thriving Haitian émigré community there. The Haitian migrants, who also cluster in New York and Miami, were labeled "the tenth department" by President Aristide, in recognition of their contribution to the national economy. It is hard to see how the country could continue to function economically without their remittances; I have never seen so many branches of Western Union in one city before.

From the palace and a couple of bland craft markets nearby, we wander south along streets where relaxed Sunday street-life (the usual fruit-and-vegetable sellers now

joined by Haitians in their best dress, heading home from the morning's church service) is punctuated by truly impressive piles of garbage. Some of them are burning or

smouldering, filling the air with a sickly-sweet smell. Again I am reminded of Managua, where trash collection and disposal takes a similarly do-it-yourself form. At one

point the road fords a small stream, and we are suddenly confronted by a scene of such medieval squalor that we can only stop and gape. The water is unspeakably

filthy, almost jet-black, little more than raw sewage; and on either side poorer dwellings and their inhabitants are clustered. I snap a photograph that will convey the image

better than my words can, and a little further along take another snap of a rubbish tip that seems to cover almost an entire block. As I do, I hear a couple of local women

behind me murmuring, and when I rejoin Miriam up ahead with Frank, she translates for me: "Why is he taking pictures of garbage?" I'm not sure I can easily answer

that one, frankly; there is always something slightly pornographic in being captivated by the dramatic poverty of others. I feel a little ashamed of myself, and decide I have

probably photographed enough trash and excrement for one day.

From the palace and a couple of bland craft markets nearby, we wander south along streets where relaxed Sunday street-life (the usual fruit-and-vegetable sellers now

joined by Haitians in their best dress, heading home from the morning's church service) is punctuated by truly impressive piles of garbage. Some of them are burning or

smouldering, filling the air with a sickly-sweet smell. Again I am reminded of Managua, where trash collection and disposal takes a similarly do-it-yourself form. At one

point the road fords a small stream, and we are suddenly confronted by a scene of such medieval squalor that we can only stop and gape. The water is unspeakably

filthy, almost jet-black, little more than raw sewage; and on either side poorer dwellings and their inhabitants are clustered. I snap a photograph that will convey the image

better than my words can, and a little further along take another snap of a rubbish tip that seems to cover almost an entire block. As I do, I hear a couple of local women

behind me murmuring, and when I rejoin Miriam up ahead with Frank, she translates for me: "Why is he taking pictures of garbage?" I'm not sure I can easily answer

that one, frankly; there is always something slightly pornographic in being captivated by the dramatic poverty of others. I feel a little ashamed of myself, and decide I have

probably photographed enough trash and excrement for one day.

At the end of Rue Capois, we come across one of Port-au-Prince's most renowned institutions -- the Oloffson Hotel. It may, in fact, be the "best-known hotel in the Caribbean," as the Miami Herald called it in October 1986. It began life as a private residence in 1887, one of the grander of the "gingerbread mansions" erected in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and was used by U.S. occupying forces as a hospital in the 1920s. As a hotel, the Oloffson was immortalized by Graham Greene, who used it as the model for his Hotel Trianon in The Comedians. The hotel's brochure emphasizes that the swimming pool outside features prominently in the novel, though without mentioning why: it serves as the venue for the suicide of one of the characters. Greene's description of the Trianon/Oloffson was a memorable one: "The architecture of the hotel was neither classical in the eighteenth-century manner nor luxurious in the twentieth-century fashion. With its towers and balconies and wooden fretwork decorations it had the air at night of a Charles Addams house in a number of The New Yorker. You expected a witch to open the door to you or a maniac butler, with a bat dangling from the chandelier behind him But in the sunlight, or when the lights went on among the palms, it seemed fragile and period and pretty and absurd, an illustration from a book of fairy-tales."(4) The heart of the Oloffson was its bar and veranda, where influential Duvalierists rubbed shoulders with visiting journalists, diplomats, and renowned literary figures: apart from Greene, the guest-list included Noel Coward, John Gielgud, and Mick Jagger.

In 1986 it appeared that the long reign of the Oloffson had come to an end. Its owners, disenchanted by the loss of a privileged relationship with the government after Baby Doc's departure, had closed it and sold off most of the furniture. But the following year, the year of the building's centenary, two graduates of Princeton University, Blair Townsend and Richard Morse (the latter a half-Haitian, one of whose distant relatives had built the edifice in the first place), bought the Oloffson, restored it, and reopened for business. Townsend commented to The New York Times in 1988 that the hotel was a sure bet: "If there's trouble [in Haiti], we take care of the people attracted to the country by trouble. If there's peace, we're going to have tourists. We're ready either way."

A handful of package tourists did indeed arrive as we lounged in the bar and sipped Cokes, but the place was hardly packed; its somnolence seemed part of its charm. Miriam struck up a conversation with one North American who was visiting her friend -- the wife of the Canadian ambassador. Both the ambassador and his spouse were enjoying lunch on the veranda, and Miriam chatted briefly with them, mentioning that we'd planned to stop by and register at the embassy when we had the chance. Both told Miriam that to do so was a very good idea indeed.

Returning, we bump into none other than Richard Morse, who in addition to running the hotel fronts one of Haiti's leading bands, RAM -- one of whose records, Puritan Voudou, provides the name for this journal, and which has just returned from a 30-date concert tour in Europe. Morse's business partner, Blair, returned to the States after just a year in Haiti, but he stayed on, married a Haitian woman, and has successfully re-established the Oloffson as a leading Port-au-Prince institution. He is an unflappable kind of guy, probably a prerequisite for managing a business in Haiti, and answers a couple of my questions easily; he has had no shortage of such interrogations, given that most visiting journalists seem to either stay at the Oloffson or pass through its gates during their sojourn to what Graham Greene called "the dark republic." How's business at the hotel these days? I ask Morse. "It goes up and down," he tells me. "It hasn't changed since I reopened the place in November 1997. This is, like, my eighteenth government" -- he is exaggerating for effect, I trust. "This is what we deal with. This is what we do."

Where does the majority of his clientele come from? "You get a pair of tourists every three or four weeks or so. But you get journalists, filmmakers" -- there is a photo of him with the American director Jonathan Demme prominently on his office wall -- "art collectors, doctors, nurses, missionaries, people looking to do music. Famous people come and go." I wonder whether the Oloffson, in his view, has managed to maintain its role as a social club and gossip centre for Haiti's upper crust. "Kingmakers!" he agrees. Will he be sticking around for a while yet? "I don't plan ahead," he replies. "I just do my thing."

The Oloffson has one computer with Internet access, which we rent for an hour and use, all three of us, to dispatch messages of safe arrival to family and friends back home. Then we take our leave and walk, a fierce sun beating down, back along Rue Capois and Avenue John Brown to the shade and exquisitely cold beer of the hospice. Another evening passes at the computer, restoring the damaged text of yesterday and writing today's entry, while fireworks again arc into the sky and music drifts on the air. This time the song hails from an island a little south of Hispaniola, and every note and word of it is etched in my heart:

Oh pirates yes they rob I

Sold I to the merchant shipMinutes of the day took I

From the bottomless pit.

But my hand was made strong

By the hand of the Almighty

We flowered in this generation

Triumphantly.

It is Bob Marley's "Redemption Song," surely one of the loveliest melodies and lyrics ever written: a celebration tinged, in Marley's aching vocal, with an almost unbearable melancholy. The hope expressed in the opening verse reminded me of the euphoria in Haiti following the popular overthrow of the dictator Duvalier in 1986; but as in Marley's native Jamaica, any dream of a triumphant flowering had been cruelly dashed since, even with the people's hero -- Aristide -- now in power. I recall a passage from Amy Wilentz's The Rainy Season, published in 1989: "It took me a little while to realize that if you wait long enough in Haiti, and really not so long, the tyranny and violence is likely to return, and that a people's victory is not always in the end what it seems to be in the beginning."(5)

"I don't know about you," Miriam says, "but my senses are completely overwhelmed."

We are walking along a street in the suburb of Pétionville that is choked with Haitians doing their pre-Independence Day shopping. The crush of humanity, the musky smell of fruit and sweat, the bleating of car-horns, the cacophonous cries of the market vendors -- all indeed made for a dizzying sensory overload. Both of us had been expecting a green and leafy preserve of the rich and super-rich -- that is Pétionville's reputation.(6) And on the ride up Avenue John Brown, we have indeed seen some opulent homes on the hilltops, with poor dwellings spilling precariously down the sheer, eroded sides of the heights. But Pétionville itself, despite a few chic shops, higher-quality vehicles, and the first white faces we have seen outside the Hospice St. Joseph and the Hotel Oloffson, seems little different than downtown Port-au-Prince -- if anything, more congested and raucous. The mansions of the elite, it seems, are some distance away from the grid of narrow streets that constitutes the heart of the 'burb.

We had planned to spend the day doing some bureaucracy downtown: banking, registering with the embassy. But Sister Maureen, Ellen's sidekick who announced yesterday at dinner that she is entering the fiftieth year of her religious service, is heading up to Pétionville to make some purchases for the hospice. She invites us to catch a ride in the hospice's four-by-four, piloted by an amiable young Haitian assistant, Francie. And so we find ourselves trying to get our bearings amidst the throngs and chaos. A couple of people, mulatto English-speakers, kindly stop to give directions.

Never let it be said that Haitians are not generous. In fact, one of them -- a perfectly ordinary bank clerk -- tries to give us US $400 that we didn't ask for. We are in a branch of Sogebank, blissfully air-conditioned, with a sign on the wall that catches our attention: "Notice to all: All transfers with Western Union to COLOMBIA must not exceed US $1,100." Hundreds of millions of dollars in Colombian cocaine moves through Haiti each year, bringing a much-needed subsistence to some of the country's poorest people, but also making Haiti one of the latest target in the U.S.'s pyrrhic and cynical "war on drugs," and fuelling a surge in gang-related violence in the bidonvilles, or shantytowns. Again the Nicaraguan comparison is inescapable.

At the counter, we deal with a pleasant young man who tells us his family is divided between Cuban and French backgrounds -- which explains his passable Spanish. (It is

said that with the traffic back and forth across the border with the Dominican Republic, notably by Haitian cane-cutters whose seasonal migrations to Dominican fields

have provoked sharp words between the two countries, many Haitians have in fact picked up a little Spanish. Walking downtown yesterday, I'd heard one local say to

another, "Muchas gracias.") We are trying to change US $100 into Haitian gourdes, currently at 25 to the dollar.(7) What we end up with is a pile of bills, most of them

matted together from the humidity and some seemingly on the verge of disintegrating in our hands. A bit bemused by the stack, we thank the gentle clerk and repair to a

corner of the bank to stash our loot in my money neck-pouch, which I have instead been looping around my belt and dangling down the inside of my trouser-leg: more

comfortable and less conspicuous. But something is wrong. We look at the receipt we've been given -- US $500 changed, more than 12,000 Haitian gourdes received in

return. A clerical error has just handed us about a year-and-a-half's income for the average Haitian family.

At the counter, we deal with a pleasant young man who tells us his family is divided between Cuban and French backgrounds -- which explains his passable Spanish. (It is

said that with the traffic back and forth across the border with the Dominican Republic, notably by Haitian cane-cutters whose seasonal migrations to Dominican fields

have provoked sharp words between the two countries, many Haitians have in fact picked up a little Spanish. Walking downtown yesterday, I'd heard one local say to

another, "Muchas gracias.") We are trying to change US $100 into Haitian gourdes, currently at 25 to the dollar.(7) What we end up with is a pile of bills, most of them

matted together from the humidity and some seemingly on the verge of disintegrating in our hands. A bit bemused by the stack, we thank the gentle clerk and repair to a

corner of the bank to stash our loot in my money neck-pouch, which I have instead been looping around my belt and dangling down the inside of my trouser-leg: more

comfortable and less conspicuous. But something is wrong. We look at the receipt we've been given -- US $500 changed, more than 12,000 Haitian gourdes received in

return. A clerical error has just handed us about a year-and-a-half's income for the average Haitian family.

We return it to the clerk, of course. We have probably just saved his job, and he knows it: "I don't know how to thank you," he gushes. I reply: "Haitian people have been very kind to us. We wouldn't want to take advantage." We leave, confident that the good karma we've gained will deliver us from evil for the rest of the trip.

We spend half an hour or so in the Promenade Café Terrace, a pleasant and slightly ritzy establishment that is more in keeping with our preconceptions of Pétionville, and sip a couple of Cokes. To return to town, we catch for the first time one of the tap-taps, converted pickup trucks, that are the essential means of town travel for all but the elite. It whisks us efficiently down the hillside to the Haitian Press Centre, which has become our landmark for recognizing the turnoff to the hospice. "This is just what we needed in Vancouver during the last bus strike," says Miriam.

New Year's Eve. It is the biggest night of the year in Haiti, spilling into Independence Day tomorrow, and Sisters Ellen and Maureen have invited us to accompany them back to Petienville, to a restaurant called La Voile (The Sail). Meeting us there are Harry and Jerry, two Catholic religious who have lived in Haiti for many years, and Anne, who runs the Fonkoze micro-credit project in Haiti. She promises us she will come to dinner at the hospice tomorrow, and I trust I will have more to say to you then about her and this important initiative. We enjoy a sumptuous meal, French onion soup and filet mignon for me, with a couple of delicious rum sours to wash it down. The restaurant is booked solid for the night, but for most of our meal we are the only customers -- Haitians apparently begin their festivities later in the evening. As we reach the end of the feast, one other party arrives -- that of the Haitian prime minister, Jean-Marie Chérestal, whose arrival is preceded by a quick reconnaissance carried out by his security detachment, including a rather striking policewoman (it is said that President Aristide, too, prefers tough female security guards). I invite her to pose for a photo, and on our way out, I stop by the prime minister's table. In my fractured French, I wish him and his companions -- including his second wife, an attractive mulatto woman -- a happy new year and best of luck for 2002. Nobody at our table has had a sympathetic word for the P.M., and according to them, just about nobody else has either. He is widely viewed as an ineffective and self-indulgent leader. But I am a fame-slut of long standing, and can't resist the opportunity to say hello.

Though we are all a little catatonic from the food and the fatigue of a long, hot day, Miriam and I stay up with Sisters Ellen and Maureen to ring in the new year. Towards midnight, the fireworks that have punctuated the evening rise to a crescendo, mingled with another sound. "Those are gunshots," Ellen says. "You should probably move away from the balcony. You don't want to get hit with a stray bullet." I follow her advice. Champagne is tippled as 2001 becomes 2002. Then we head to bed. I am awakened several times throughout the night by the revelries outside -- singing in the streets and at early-morning church services, laughter, half-a-dozen portable stereos pounding out competing tunes and musical genres. This Creole gumbo of noise is somehow comforting, and each time it wakes me, I soon drift back to sleep.

There is very little happening on New Year's Day -- we are told that it is mostly an occasion for family visiting rather than wild celebrations downtown -- and so we lounge around the hospice all day, reading and getting caught up on journal writing. Miriam finally manages to get a collect call through to her fiancé back in Vancouver, and is extra cheerful for a while afterwards. In the evening, with a flood of guests due to return to the hospice from project work in the highlands, I am asked to shift my gear to a room on the second floor. It has the advantage of fewer mosquitoes (though I have yet to receive a noticeable bite; Miriam, for her part, is being eaten alive), but is also that much nearer to the street noise, which begins promptly at 5:30 in the morning with a crescendo of stereos, ill-tuned vehicle engines, and raucous laughter.

The 2nd is also a public holiday, and we decide to spend it in and around the small town of Kenscoff in the hills above Pétionville. It is known as the "Switzerland of the Caribbean," largely owing to its precipitous topography, its pine forests, and the 2000-metre elevation that cools the air -- an attractive prospect after the swampy air of Port-au-Prince. We catch a tap-tap to Pétionville and arrive to find a truck loading up for Kenscoff; but it is already crowded, and I suggest to Miriam that we wait for the next one. We are used to a tap-tap passing every five seconds or so (how fucked-up does a country have to be before its public-transit system is less efficient than Vancouver's?), but transport to Kenscoff is more sporadic, and we wait by the busy food market at the corner of Rue Grégoire and Rue Villette for forty minutes or so. To help pass the time, I buy a copy of Haiti Observateur from a street-seller. It is a weekly, edited in New York by Haitian émigrés, and its tone is scabrously reactionary, in a way that reminds me of some of the venomously anti-Sandinista La Prensa in Nicaragua during the revolutionary years. Predictably, it is President Aristide that is the target of the most colourful abuse. The front-page headline reads, "Le terroriste Jean-Bertrand Aristide, piégé dans ses macabres scénarios," and the diatribe, by one Dr. Gérard Gourgue, begins as follows:

"Le terroriste Jean-Bertrand Aristide, après avoir incendié maisons et bureaux du Directoire de la Convergence démocratique, après avoir assassiné parents et gardiens des foyers affectés á la recherche des travaux d'une ONG sous la direction de Gérard Pierre-Charles, tout cela á la suite d'un scénario visant l'assassinat des leaders et des militants actifs de l'oppoisitionofficiellege, continue de plus bel ses opérations tyranniques. ...

An inside article titled "Control of Aristide's armed militias" strikes a similar tone:

"Jean-Bertrand Aristide prétend être président d'Haïti. Il prétend ne pas avoir de contrôle sur ses milices qui terrorisent l'opposition. Si c'est vrai on peut comprendre pourquoi il est incapable de négocier, puisqu'il est complètement dépassé par ses propres troupes qu'il ne peut pas contrôler."

It perhaps says something for President Aristide that he has placed no restrictions on the circulation of Haiti Observateur, a point made earlier by Alex Dupuy in his fine little book, Haiti in the New World Order: "Unlike previous regimes, the Aristide government never suppressed that journal or any other from circulating freely in Haiti, despite Haiti Observateur's unrelenting and sometime vitriolic attacks against Aristide and his government during its seven months in office [in 1991]. One need only compare the state of terror under which the media existed in Haiti during the three years of the coup d'état [1991-94] to appreciate the difference that Aristide made. This fact, of course, is characteristically overlooked by Aristide's detractors."(8) There is, though, a good deal more to say about media freedom in Haiti, which has been a focal point of the regime's critics, by no means all reactionary. We are hoping to elicit some comments from a few of the country's journalists on this score in coming days.

Finally a Kenscoff-bound tap-tap rolls into view, and we jump aboard gratefully, exchanging "Bonjous" with our fellow travelers -- a little ritual that never

seems to vary, and that pleases me. The vehicle follows a winding, decently-surfaced road -- we are, after all, in the stomping grounds of the Haitian elite, which would

not wish to strain the shock absorbers of its Mercedes and BMWs. As we ascend we begin to pass some of the mansions that we had expected to see in Pétionville

proper. They are spectacular, and spectacularly incongruous, in this setting -- often three or four storeys high, containing God knows how many dozen rooms and

servants, with satellite dishes that would make NASA envious.

Finally a Kenscoff-bound tap-tap rolls into view, and we jump aboard gratefully, exchanging "Bonjous" with our fellow travelers -- a little ritual that never

seems to vary, and that pleases me. The vehicle follows a winding, decently-surfaced road -- we are, after all, in the stomping grounds of the Haitian elite, which would

not wish to strain the shock absorbers of its Mercedes and BMWs. As we ascend we begin to pass some of the mansions that we had expected to see in Pétionville

proper. They are spectacular, and spectacularly incongruous, in this setting -- often three or four storeys high, containing God knows how many dozen rooms and

servants, with satellite dishes that would make NASA envious.

Kenscoff itself, 15 kilometres from Pétionville, is a bit of a letdown: barely a village, clustered at a single intersection with a few wan dwellings straggling down side-streets. Its highlight appears to be a rollerblading rink, of all things, though we neglect to peek inside. The attraction lies rather in the dirt roads that lead away from the settlement, offering dramatic vistas of steep mountains and chasms. The air is wonderfully cool and fresh, scented with flowers and donkey-dung, and peopled with friendly Haitian peasants who call out sing-song "Saluts" as we pass them on the trail. We cannot claim to be in the countryside proper, since the presence of the rich nearby means that there is something of an infrastructure here -- the power lines strung across the road are its most noticeable sign -- and we have already chatted with foreign religious who live in villages with no electricity or running water, and the nearest telephone three miles away. But it is gratifying to have this glimpse of greenery and taste of sweet air after the boisterous, sweaty jostle of Port-au-Prince.

On the way back down to Pétionville, we stop at the restaurant of the Hotel Florville, a kilometre or so outside Kenscoff. It is deserted when we arrive, though a handful

of other customers wander in as we wait, and wait, for our food to arrive. We snack on a plate of rice and sautéed onions; I knock back a brisk glass of Barbancourt

rum, Haiti's finest; and we are back on the road. At my left elbow in the tap-tap is a handsome young couple. The man is softly singing a selection of Bob Marley's

greatest hits, including -- you guessed it -- "Redemption Song." I join in on the chorus, and he smiles in acknowledgment: "Don't you love the words to that song?" As

you already know, I do.

On the way back down to Pétionville, we stop at the restaurant of the Hotel Florville, a kilometre or so outside Kenscoff. It is deserted when we arrive, though a handful

of other customers wander in as we wait, and wait, for our food to arrive. We snack on a plate of rice and sautéed onions; I knock back a brisk glass of Barbancourt

rum, Haiti's finest; and we are back on the road. At my left elbow in the tap-tap is a handsome young couple. The man is softly singing a selection of Bob Marley's

greatest hits, including -- you guessed it -- "Redemption Song." I join in on the chorus, and he smiles in acknowledgment: "Don't you love the words to that song?" As

you already know, I do.

We strike up a conversation, with Miriam translating from the French. He is a psychologist working on a project for Port-au-Prince children with AIDS. He asks what we're doing in Haiti, and Miriam explains our interest in the progress of democracy and human rights. Does he have any comments? I ask. He grins. "Oh, I could make plenty of comments." He points out that when Aristide was returned to power in 1994, he landed in the capital on a U.S. aircraft, accompanied by U.S. Marines. "So now," he adds a little cynically, "the people think democracy can arrive on an airplane, because that's how Aristide came back." Then he says something that sticks in my mind: "Haiti is a flame that will never die. Do you know why? Because it's my country." Another grin. "But in order for it to stay my country, I have to work at making it a better place." A couple million more like him, and this land could stand a chance.

Fonkoze is trying to empower the poor. Fonkoze is trying to build a democratic economy in Haiti. Without that, democracy cannot work in Haiti. - Anne Hastings

Anne Hastings, who joined us for New Year's Eve celebrations at La Voile, was working as a management consultant in the United States, running her own company (Scanlon and Hastings) in Washington, D.C., pulling in US $130,000 a year, when she suddenly decided there had to be more to life. "I was at a point where I was burned out. It seemed to me that nobody wanted to accomplish anything serious; there was nobody with a real vision." She thought at first of joining the Peace Corps, and was at the point of signing on the dotted line when she heard through a family friend of a priest, Joseph Philippe, "doing great work in Haiti." She got in touch and found out about his plans to start a micro-credit scheme for Haiti, along the lines of the world-famous "Penny Bank" in Bangladesh.(9) What she discovered was that "this man has more vision than all of my [former] clients put together. But there was no way he was going to get there from here." With her management background, she thought she could lend a hand; "I felt I was good at getting into an area I knew nothing about."

When word got out in her circle of friends about her "crazy" plans, small cheques began to arrive in her mailbox. She ended up with $12,000, put her car on a container vessel to Port-au-Prince, and in May 1996 moved to Haiti to work with Father Joseph on Fonkoze (the Fondasyon Kole Zepòl: "Shoulder to Shoulder" in Creole). Five-and-a-half years later, Fonkoze is one of the success stories of Caribbean development initiatives, with 18 branches across the country, 174 employees (most of whom, according to Anne, have never held a job before), 20,000 accountholders, and $2.75 million in savings. Anne has never drawn a salary from the project; she relies instead on $6,000 a year from the San Carlos Foundation, which funds volunteer professionals worldwide. Quite a change of lifestyle, but Anne has no regrets. "It's the best decision I've ever made. It has totally transformed my life. I've never been a particularly religious person, and I'm not sure I am today. But I do believe I have been very, very blessed in the time I've been here. And I feel I've seen God in the faces of the Haitian people. There are maybe little tiny periods when I feel I want certain material things, but they're few and far between -- and that's an amazing thing to have happen in my life."

We are chatting with Anne in her pleasant, spacious office on the top floor of the Fonkoze building in downtown Port-au-Prince, a short walk down Rue Capois from the Hotel Oloffson. Entering the place is something of a challenge: we are carefully bag-searched and metal-detected, our cigarette lighters confiscated, and our credentials carefully checked before we are ushered upstairs. This is a long way from paranoia, as will become clear below. The office is a hubbub of activity, with a team of workers busy balancing the monthly books.

The strategy of Fonkoze is straightforward. As its 2000 annual report describes it, "Fonkoze uses a methodology called 'Solidarity Group Lending.' In this system, a group leader chooses four other group members and a name for the group. After a training period, they receive an initial loan from Fonkoze. This loan might be about US $60. The group is responsible for paying back this loan; so, if one member does not repay, the others must cover the loss." "People resist going into a solidarity group at first -- in fact, they'll do anything to avoid it," Anne tells us. "But after three years, they don't want to leave."

The report continues: "Members also have an incentive to repay because they can receive a second larger loan, and so on. They pay interest rates designed to cover Fonkoze's administrative costs, but set much lower than the exploitative rates of money lenders (often 100-300% [annually]) who are their only alternative. Fonkoze's default rates are less than 5%. Over 80% of Fonkoze's borrowers are women," the large majority from the so-called ti machann, the street vendors who are such a ubiquitous sight along Haiti's roads and sidewalks. The key is outreach: Fonkoze goes where Haiti's banking system, which is far more advanced and sophisticated than most sectors of the economy, has standardly refused to tread -- into the countryside, where the need for such micro-credit is every bit as powerful as in Port-au-Prince. Now the commercial banks are rushing to follow Fonkoze into the countryside. "We've demonstrated that even in rural areas, you can make a bank work," Anne says with satisfaction. The longterm objective is to get ti machann out of the informal and into the formal business sectors -- to promote the creation of new so-called "Madame Saras," the businesswomen who ply their trade around the Caribbean, and are often to be seen at Port-au-Prince airport burdened down with goods from the Dominican Republic or elsewhere. As such, they are able to sell to other ti machann, rather than supplying end-users at streetside.

Fonkoze is registered as a foundation, the membership of which consists of various organizations -- agricultural coops, peasant associations, ti machann groups -- who send representatives to a General Assembly that serves, in Anne's words, as "a training ground in democracy." Its main investors have been foundations, female religious communities, and ordinary individuals in the developed countries. "A lot of individuals make a $1,000 investment," says Anne. "They love this concept that they're not giving this money, but lending it to us, and the money is being lent out over and over again." The money is returned after a couple of years with nominal interest or, as many investors prefer, none at all. The foundation also receives money from various supportive organizatins through USAID, though it strictly preserves its autonomy from that ambiguous organization. It refuses to accept any funding whatsoever from the World Bank or International Development Bank, fearing that such contributions would be accompanied by requests for a place on Fonkoze's board of directors. Onward and upward: the foundation is now positioning itself "to spin off its financial services to form Haiti's first micro-credit oriented commercial bank," according to the annual report. The bank will be 51% owned by the foundation and selected other Haitians, "to ensure its classification as a Haitian-owned bank."

To my surprise, Anne says that Fonkoze cooperates closely with Haiti's commercial banks. Its relationship with Unibank, the country's second largest bank, is particularly close: "I'm very respectful of the way they've handled the relationship with us. Most banks in Haiti make a lot of their money from foreign exchange, and we've turned into an absolute vacuum-cleaner for them," collecting some $1 million a month and negotiating highly-favourable exchange rates with the commercial banks: "We give the same rate for a $20 exchange as for $100,000." Fonkoze also channels its members savings into accounts from which, thanks to its foundation funding, it has no need to draw for loans. Those accounts are then deposited in the commercial banks, who are now competing with Unibank for Fonkoze's business.

Fonkoze differs from many other micro-credit projects around the world in a couple of key ways. First, it accompanies its loan programs "by helping our clients to become financially literate and acquire business skills." Anne shows us an innovative game, called Jwèt Korelit La (Game to Reinforce the Struggle), which was developed by Father Joseph. It follows the lead of the Brazilian pedagogue Paulo Freire in encouraging ordinary people not only to learn technical terms and skills, but to reflect on what they've learned. Key terms are introduced, and "players" then invited to discuss what the concepts mean in their own lives. They then move on to draw up lists of assets, expenditures, and potential profits. Says Anne: "By the time you're finished, what you really have is a financial plan."

Another difference, as Anne notes, is that "in micro-credit circles, there is a very firm belief that micro-credit should be offered purely -- that is, you muck it up if you try to do things like literacy training that don't mix well." Fonkaze, though, considers it essential that members develop at least basic literacy skills. According to the director of the Literacy and Business Skills Training Program, Pierre Malvoisin, "Our clients … [at first] had difficulties filling out the forms. They couldn't sign anything -- they were obliged to put a cross or to put their thumbprint to sign their name. … Of course, after the literacy program they're not intellectuals. But they are able to write their name and take inventory. They have the capacity to reflect not only on their business activities, but also on their environment."

Lastly, Fonkoze is working to develop a transfer service to cater to the vast population of Haitians living overseas. They remit home $720 million a year, close to one-fifth of the country's gross domestic product; without these transfers, many Haitians would be starving rather than subsisting. Fonkoze twinned with the City National Bank of New Jersey, which has a Haitian/born CEO and president and agreed to drop all wire-transfer fees. As a result, Fonkoze can charge a $10 flat fee on transfers, instead of the standard 10-12 percent that Western Union levies. Now Fonkoze has secured a grant to conduct training programs in financial management for Haitian migrants overseas, who for the most part "are not financially literate," in Anne's words.

The course of Fonkoze's operations has not been without its potholes. There are advantages to working in a country where government regulation is nonexistent. "It was like heaven, being in Haiti where nobody would interfere," Anne tells us. "But you do need a government for certain things -- security and infrastructure in particular. It's very difficult to operate without decent roads and communication. But the hardest part, for us, is insecurity. [Describe robbery]

The project has also been marked by a shocking tragedy, one that we had learned of a couple of days previously, when Anne arrived with Fathers Harry and Gerry for dinner at the hospice. On September 6, 2000, ten armed men dressed in the uniforms of the Haitian National Police invaded the premises (using the excuse of checking staffers' gun permits) and seized one of Fonkoze's key employees, 27-year-old Amos Jeannot. They forced him into a car. He was never seen alive again; 48 hours later, his tortured and mutilated body turned up in the Port-au-Prince city morgue. He left behind a tiny baby and a family stripped of its breadwinner. Two thousand people attended his funeral, the majority of them weeping ti machann. Father Gerry presided. "The hardest homily I ever preached," he told us after dinner. "Because people don't come any better than him." The tribute from a ti machann that Amos assisted was more eloquent still: "We don't have to borrow from loan sharks anymore. It was Amos who helped us get out from under

No-one knows who inflicted the atrocity, though there are strong suspicions that it was linked to the frustrations of the loan-sharks who saw Fonkoze challenging their stranglehold over micro-credit to the ti machann. The foundation received threatening calls after Amos's abduction, telling staffers that if Fonkoze did not close, they would never get him back alive; Anne believes Amos was already dead at that point. "The killing was done as a threat to Fonkoze," she says bluntly. "It wasn't motivated by money" -- except indirectly, of course. But "quite frankly, we don't know who committed this crime and who financed it."

In the wake of the horrific act, the Haitian police provided Fonkoze with a team of three "really professional investigators, top-notch people," in Anne's estimation. "They felt after a couple of months that theyhad identified seven out of ten of those who kidnapped him. But they had to turn thejob over to another division to make the arrests." Anne kept hearing that such arrests were impending, which she dismisses as "bullshit"; the runaround continued for months, and meanwhile, five of the seven suspects were killed. "I believe they were gang members," Anne tells us. "But the people who financed them were not. But I've given up. We'll never know what happened."

If there is a silver lining to the grim tale, it lies in the fact that "Now we have more friends than we ever dreamed we had," in Anne's words. "And that is a protective shield around us. We were afraid that after Amos's death, people would close their accounts. But in the three months after he was killed, we opened more accounts than in any three-month period before or since."

For more information, contact Fonkoze c/o Lynx Air, P.O Box 407139, Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33340, USA, tel. 011-509-221-7631/7641, fax 011-509-221-7520. Anne Hastings can be reached by e-mail at fonkoze@aol.com. Tax-deductible donations can be sent to Fonkoze USA, P.O. Box 53144, Washington, DC 20009, USA.

On April 3, 2000, Haiti's most popular radio journalist, Jean Dominique, was gunned down in the parking lot of the private station Radio Haiti, along with a security guard who had tried to defend him. The killing drew fresh attention to the plight of Haiti's journalists, who feel themselves increasingly in the firing line -- though who, precisely, is doing the firing remains a matter of conjecture.(10)

In Jean Dominique's case, suspicion has centered on a member of the Senate, Danny Toussaint, who was Minister of Public Security and Safety in President Aristide's first administration (1991) and ran the security force that protected the president. Now Toussaint is rumoured to have presidential aspirations of his own, and to still control a private army that may outnumber the National Police. Allegations of his involvement in the drug trade have also swirled around him, though it is important to stress that no hard evidence has yet been adduced. What is clear is that a) Dominique had been harshly critical of Toussaint in broadcasts that aired shortly before his murder, and b) Toussaint has so far refused to surrender his parliamentary immunity from investigation and prosecution. Dominique's killing remains an open wound in the Haitian body politic. "What's ironic," one Port-au-Prince resident had told us, "is that he [Dominique} was exiled by Duvalier, came back to participate in the new democracy, and it was the democracy that killed him."

We turn up unannounced at the Radio Haiti offices, but are warmly greeted by Michele Montas-Dominique, Jean's widow, who welcomes us into her office for an interview. She is a dazzlingly regal-looking woman who serves as the radio station's editor-in-chief. Has there been any progress in the investigation into her husband's murder?

"Actually, the investigation is at a standstill right now," Michelle tells us. "It has not moved. It's stuck first in the Senate, because the investigating judge has asked that they lift the parliamentary immunity of Senator Danny Toussaint. The Senate has had the request in front of it since August 10th [2001], and nothing has happened since. So we are still waiting.

"So far we have six people in jail in connection with this case. Among them are two former policemen, one of them from the National Palace. There are also several warrants out, some for close associates of Senator Toussaint. So we assume the investigation is now moving towards that group. We don't know yet what the specific charges are, except that they are somehow implicated with the crime. That's all we know."

The failure to file proper charges in the case, says Michelle, "is what really has created the situation with the press right now. Because nothing was ever done about the person who happens to be the most famous Haitian journalist, [it seems that] anything can happen to younger and less well-known journalists.

"There has been an intolerance and a climate of violence in our country for quite a while now, and it has targeted journalists, particularly journalists who have given voice to the opposition parties. But it's quite a complicated thing, because you cannot say that the government is doing anything to the press. There is no government repression. The press is free; everyone says whatever they wish. However, when you have pressure groups, some saying they are close to the party in power, who are threatening journalists, then the situation is both confusing and dangerous for journalists. You don't know where the pressure and threats are coming from.

"That's the difference between the situation now and what used to exist. I was a journalist here under Duvalier, and also under the military regime that followed Duvalier. Back then, you knew [the pressure] was coming from the government and the army. It was a clear-cut case."

I ask her whether Radio Haiti considers itself a voice of opposition to the Aristide government. "We have always been an independent voice," she answers. "It was true under Duvalier; it was true under the military regime; it is true under the present government. Radio Haiti has a specific line, of course: that we are one of the very few radio stations that gives a voice to people who don't have a voice.

"In Haiti, 80 percent of the population is excluded from public life. The majority of people are peasants living in the countryside. We really have two countries here: we have the Republic of Port-au-Prince, and we have another country, which is the rest, okay? And what Radio Haiti has had ever since Jean owned the station, since 1970, is the tradition that we are the voice of the voiceless."

I want to ask her something about paramilitarism in Haiti: does the phenomenon, the institution, still exist here? Can it be linked to her husband's murder?

"During the coup," she says, "you had the paramilitary forces of the FRAPH.(11) They were responsible for most of the repression that took place during the coup, between 1991 and 1994. But at the same time, you had the forces of resistance that built up under the coup. When Aristide came back, they were determined never to be the victim of another coup. So you had a massive distribution of weapons in the popular neighbourhoods, particularly in Cite Soleil, the largest slum in Port-au-Prince. Some of those weapons belong to various political forces. Others come from drug money. It's really difficult, at times, to separate groups that are armed to defend the political system or a political party from the criminal element -- people linked to drugs. And they are heavy weapons. On December 17 [the day of the attempted coup, when armed Aristide supporters flooded into the city to defend their hero] I saw weapons I had never seen before.

"I have to say one thing. When the Americans landed [in 1994], and the U.N. forces too, they never disarmed anyone. The weapons from the army, from FRAPH - where did they go? You have to realize some of the FRAPH elements are still around and still have weapons. So this is, again, a very confusing picture. You have weapons all over the place.

"Are these paramilitary groups the way FRAPH was a paramilitary group -- an organized force, like Duvalier's militia, the Tontons Macoute? I don't think so. I think you have small private armies, yes. Most drug dealers have such armies. How many are they? I don't know. Does anyone have a force larger than the National Police? I don't know. I know they have forces that are better armed than the National Police."

I ask her, finally, for her personal opinion of President Aristide. "Are you optimistic at all about the direction in which Haiti is going under his leadership, or not?"

"You ask about leadership," she replies. "The problem of leadership since the coup is that Aristide has inherited a weak state. He has very little power. Before, there was always the army to back up any so-called civilian power. That's how Haitian history has been for 200 years.

"Suddenly you have a civilian government. Can [Arisitde] impose what he wants on the country, on his own people? It's obvious that he cannot. So giving you my opinion on Aristide himself is irrelevant. What is relevant is what he can control. And I'm saying that's very little. This is why so many Haitians are worried that we might be on the brink of some form of anarchy. Not because Aristide wants that anarchy, but because he does not control enough of the elements in place.

"I think the international community is playing a very strange role here, by keeping the country deprived of any type of foreign aid except that given through NGOs. The international community has been using that aid money as kind of a stick when it comes to the political crisis -- a crisis that is largely engineered by a few minds. If you ask most Haitians in the streets, 'Is there a political crisis?,' they will tell you 'no.' They know they have a crisis of everyday life -- of jobs, of opportunities of every sort, inflation. Those are the things that concern the majority of people.

"Today you see the majority of Haitians telling you that they feel more and more suspicious of any politician of any shape or colour, whether from the opposition or from the government. People feel deceived in a way, but I think their disillusion is towards every politician. And the situation is getting worse, essentially because the economic situation is getting worse. So is there a human rights problem in Haiti right now? Yes. But it's essentially a question of economic and social rights. That's the way I feel."

Time for a break.

At six o'clock we are up and packing; a quick cup of coffee and a toasted bagel (in Haiti? Yes -- purchased from the Baptist Mission on the Kenscoff road, which proudly advertises its product as unique in the country. It is Epiphany and the sisters at the hospice have decided to treat themselves), and we are strolling down to Rue Christ Roi. There we hop into our first publique, the system of rattly old vehicles that ply the streets of Port-au-Prince with red ribbons dangling for their mirrors, and will take you anywhere in the city for a song, if it happens to be in the rough direction they're travelling. A few minutes later we are downtown, by the sports stadium, where buses are assembled to take us to our destination -- Jacmel, on the south coast of Haiti, one of the few sites that can still claim to have something of a tourist industry. We are about to climb onto an old, gaily-painted bus, when we are directed instead to a different vehicle -- modern (!), air-conditioned (!!), with a hostess who assigns every passenger a laminated ticket and records his or her name on a list … It is all a bit of culture shock.

The bus spends its first twenty minutes trying to leave the depot -- we are at a major intersection with traffic lights that are out of order, and so drivers must negotiate their way across. It is a painstaking process, but carried out without shouts and fist-waving -- evidence that anarchy is not, after all, chaos. Then we are inching our way through the people-choked streets of Carrefour, the southern suburb that is notorious as a perpetual traffic-jam, before reaching the main southern highway. It is a narrow but excellent road (!!!) that follows the shoreline for a couple of dozen kilometers, through lush fields of sugar-cane, before heading in land and negotiating twisting, hairpin bends up into the cordillera. The driver turns the air-conditioning off and, as the passengers in unison tug open their windows, we are greeted with streams of fresh mountain air. Our soundtrack is some thrilling music over the bus's sound system -- the Haitian version of Dominican merengue, known as compas, which has many of the passengers rocking in their seats, ourselves included. The views are spectacular, with precipitous terraced mountainsides (stripped of most of their forest cover) spilling into valley wedges, concrete dwellings and grass huts dotting the landscape. Before long, we have crested the cordillera and begin the descent to the wide bay of Jacmel and the funky, sleepy little town strung along it.

Reading the Lonely Planet guide on the way in, I'd been struck by a sentence I'd somehow overlooked until now: "[Carnival] festivities take place every Sunday starting on Epiphany, the 6th of January, and culminate on Mardi Gras, the Tuesday before Lent." Jacmel is renowned as home of the most boisterous Carnival celebrations in Haiti. We have really lucked out.

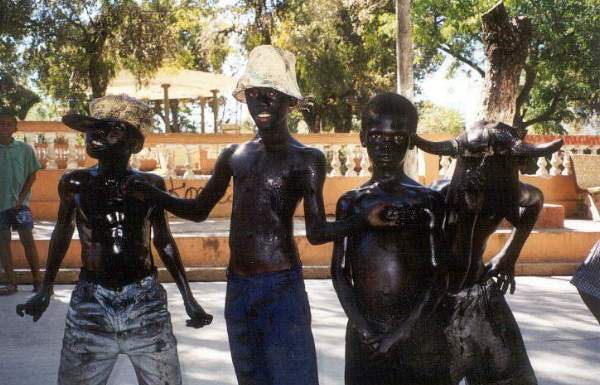

We take a room at Guy's Guest House, at $32 a night. "At least Haiti'll be cheap," friends had commented before we left, but it isn't (the room we have in Jacmel could be had for $12 in Mexico). In an economy where only a small percentage of the population, along with foreign visitors, has disposable income, there is no incentive to keep prices low. But Guy's is clean and friendly. We stow our bags and head over to the Hotel de Place, on the central square; entering, we're nearly run over by a half dozen raucous kids, jet-black. I know 95% of the Haitian population is of pure African descent, but these kids are black, like animated ebony statues, and it takes us a moment to figure that they are daubed from head to toe in what looks like pitch -- though Miriam manages to find out that it is in fact ash mixed with cane syrup. Why every fly on Hispaniola isn't clinging to them is beyond me, but they are quite a sight, and I line them up for a couple of photos, pressing a dollar into the hand of the self-appointed leader afterwards. (Haitians are notoriously camera-shy -- the U.S. Consulate fact-sheet warns tourists against taking photos without permission, claiming it has "led to violence" on occasion -- and most up-close people-shots have to be negotiated for a price. This time I feel I'm getting a bargain.)

We sit on the veranda of the hotel and nibble on fried plantains and salad, a fine light lunch, watching the somnolent life of the Place d'Armes and chatting with Sarah and Jean-Marc -- two young, genial Louisianans who met doing volunteer work at an orphanage in Kenscoff, fell in love, married, and are now on their honeymoon. They have walked from Kenscoff to Jacmel -- not quite as daunting as it sounds, since the hike can be done in a day by dedicated hikers (they took their time and overnighted en route). Jean-Marc regales us with some horror stories of his time working as a medical assistant in Cité Soleil: "What we saw mostly was people with sores that just wouldn't heal. There's so much garbage and sewage running through the place that cuts get infected and stay that way. We'd clean them and dress them, get them to come back a few days later, repeat the process, and hope that would be the end of it." We shiver inwardly. "But that's not the worst of it … do you know the Ville Carton, the cardboard slum?" We don't, but can imagine. "Cité Soleil is decent by comparison."

An after-lunch nap, and then we head out to explore Jacmel in earnest. The town has a fascinating history. In 1698, the French "officially inaugurated [it] as the capital of

the South East Colony, 50 years before the creation of Port-au-Prince. … By the 18th century, Jacmel was one of the most important judicial centers in Haiti." It was a

central player in the independence struggle of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and also figured in the wider movement for Latin American independence:

An after-lunch nap, and then we head out to explore Jacmel in earnest. The town has a fascinating history. In 1698, the French "officially inaugurated [it] as the capital of

the South East Colony, 50 years before the creation of Port-au-Prince. … By the 18th century, Jacmel was one of the most important judicial centers in Haiti." It was a

central player in the independence struggle of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and also figured in the wider movement for Latin American independence:

In 1806 Venezuelan revolutionary Francisco de Miranda stayed in Jacmel and designed the flag that would become the banner of Simón Bolívar's liberation army. In 1816 Bolívar himself spent a brief time in a house on the main square while he assembled his revolutionary army. Around two hundred Haitian volunteers joined Bolívar when he left to free South America from the yoke of Spanish colonialism.

By the middle of the 19th century, Jacmel played a vital role in trade with Europe. Cargo, mail and voyagers from throughout the Caribbean region gathered here to meet steamships boundfor Britain. You can still find the names of many Europeans on the gravestones in the cemetery, a testament to those more cosmopolitan days. By the late 19th century Jacmel was a prosperous coffee port. It was the first town in Haiti to have telephones and potable water, and when the Cathédrale de St. Phillippe et St. Jacques was lit up on Christmas Eve 1895, Jacmel became the first town to have electric light. The city center was destroyed by a huge fire in 1896 and then rebuilt in the unique Creole architectural style that remains to this day.(12)

Despite the decline of its fine buildings, Jacmel remains in the vanguard of Haitian development. It is notably cleaner and tidier than Port-au-Prince, with none of the garbage piles and open sewers of the capital. The residents seem, if not exactly prosperous, reasonably well-off. Public services also seem less of a joke here. Roads are good. The country's first town with electric light experiences no power-cuts in our 48 hours thereabouts; it is a rare day indeed (usually a major national holiday) that one enjoys constant current in Port-au-Prince. And the future may be brighter still: the wharf is currently undergoing restoration, in anticipation of cruise ship passengers who are scheduled to begin disembarking from two separate cruise lines in the next few months.