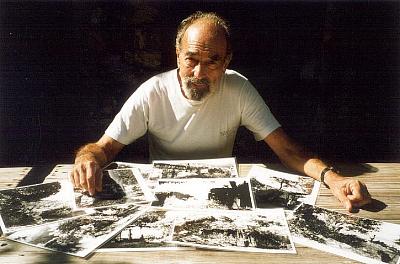

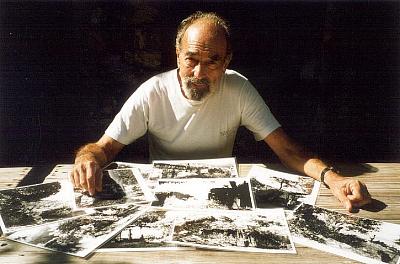

Norman Zarchin, proprietor of Norm's Place

in Labadie, Haiti

Note: Larger versions of the photos that accompany this article

can be found in the Haiti Photo Gallery #6.

"This place is nuts," said Miriam.

We were standing outside the front door of Norm's Place in Labadie, Haiti, a small fishing village a few kilometres along the coast from the fabled city of Cap-Haïtien. And "nuts" can be taken two ways. Miriam thought last night's accommodations were pretty nuts, too, as did I. We ended up at Plage Belli, a tiny cove across the bay from Labadie, to stay at the Belli Beach Bar. Our guidebook assured us it was an "almost-perfect" beach resort, with plenty of atmosphere at a budget price. When we arrived at the end of the path to Belli, however, the proprietress of the Beach Bar seemed slightly stunned to see us. Our room featured a moldy bed and a surfeit of mosquitoes, which we kept barely at bay by burning foul-smelling insecticide coils. The generator had failed, and we were left in the hands of the municipal authority in Cap-Haïtien, which delivered us all of two hours of power during the night.

Miriam didn't sleep much at all. But we managed to glean one useful piece of information from the Haitian boys who

dropped by our beach to chat us up and try to wangle a few dollars. There was a place to stay at Labadie village: Norm's

Place. It had hammocks, that was all we knew. And so we found ourselves buzzing across the bay on a small launch to the

jetty at Labadie -- a somnolent, tidy village of about four thousand souls, in which Norm's Place was not immediately visible.

A local guided us through sandy backyards and alleyways, and forded us across a little stream to Norm's. I was anticipating

a ramshackle hut with a couple of hammocks strung on the porch.

Miriam didn't sleep much at all. But we managed to glean one useful piece of information from the Haitian boys who

dropped by our beach to chat us up and try to wangle a few dollars. There was a place to stay at Labadie village: Norm's

Place. It had hammocks, that was all we knew. And so we found ourselves buzzing across the bay on a small launch to the

jetty at Labadie -- a somnolent, tidy village of about four thousand souls, in which Norm's Place was not immediately visible.

A local guided us through sandy backyards and alleyways, and forded us across a little stream to Norm's. I was anticipating

a ramshackle hut with a couple of hammocks strung on the porch.

Imagine my surprise.

We passed a couple of palm trees and a low stone wall, to find ourselves at a doorway, constructed from local brick and stone, that led into a veritable oasis of calm and good taste. It was what passed for a lobby, dining room, and sitting room at Norm's, and it featured exquisite mahogany furniture in the colonial style, arrayed across a tile floor and with walls adorned with Haitian ironwork, wood carvings -- and slave manacles.

Jaws dragging along the sand by this point, we were shown two of the five rooms at the inn: wonderfully spacious and cool, with mosquito nets draped over quilted beds, more mahogany furniture, a sunken shower-stall … After three weeks in Haiti, most of it spent in the vibrant madhouse of Port-au-Prince and the busy streets of Cap-Haïtien, to be surrounded by luxury and elegance was thoroughly surreal. To gain access to it would cost more than we were planning to spend, but if ever there were a time for a splurge, this was it.

Norman Zarchin and his Haitian wife, Angelique, were away for the first few hours of our stay: we were arriving

without reservations, which are recommended. They had taken the day to pop across to Plage Labadie, which is currently

the one Haitian tourist spot that cruise passengers have a chance of encountering. The Royal Caribbean lines operate a

"Fantasy Island"-type resort at the Plage, on a walled-off peninsula that we had skirted earlier that morning, trying to see if

we could get inside for a decent breakfast after our rustic night. But without the plastic wrist-bands to demonstrate that we

were good paying customers of Royal Caribbean, we were as frozen out as the knots of Haitians that gathered at the gates.

Norman Zarchin and his Haitian wife, Angelique, were away for the first few hours of our stay: we were arriving

without reservations, which are recommended. They had taken the day to pop across to Plage Labadie, which is currently

the one Haitian tourist spot that cruise passengers have a chance of encountering. The Royal Caribbean lines operate a

"Fantasy Island"-type resort at the Plage, on a walled-off peninsula that we had skirted earlier that morning, trying to see if

we could get inside for a decent breakfast after our rustic night. But without the plastic wrist-bands to demonstrate that we

were good paying customers of Royal Caribbean, we were as frozen out as the knots of Haitians that gathered at the gates.

On the water-taxi over to Norm's, I'd photographed local boats alongside the massive bulk of the Voyager of the Seas, which had just pulled into port for its epic eight-hour stay in Haiti. (Word has it that in the past, passengers were not even told they were in Haiti, but rather paying a visit to somewhere called "Paradise Island.") Soon enough, the ship's water activities got underway, and a fleet of tourist kayaks paddled its way around the bay. I watched them pass by from a spot on the beach, and the guide shouted out: "It's Norm. Hey, Norm!" For a brief moment, before I could clarify, I had become a local notable.

Before the kayakers headed back to their air-conditioned beehive (you poor slobs, I thought), the guide told them, and me, a

little about my new surroundings. I was staying in a small complex of stone buildings, parts of which dated back to the late

French colonial era, when Haiti -- then called Saint-Domingue -- generated more wealth for the metropolitan power than any

other colony on earth. The fertile North Plain of Haiti, a territory measuring about 50 miles by 20, was home to hundreds of

plantations (indigo, cotton, coffee, tobacco, and above all sugar) exploiting hundreds of thousands of slaves.

Before the kayakers headed back to their air-conditioned beehive (you poor slobs, I thought), the guide told them, and me, a

little about my new surroundings. I was staying in a small complex of stone buildings, parts of which dated back to the late

French colonial era, when Haiti -- then called Saint-Domingue -- generated more wealth for the metropolitan power than any

other colony on earth. The fertile North Plain of Haiti, a territory measuring about 50 miles by 20, was home to hundreds of

plantations (indigo, cotton, coffee, tobacco, and above all sugar) exploiting hundreds of thousands of slaves.

"On no portion of the globe did [the] surface in proportion to its dimensions yield so much wealth," according to the great historian of the Haitian revolution, C.L.R. James. Haiti was the main engine of France's overseas empire, and it supported several million French men and women who processed the produce of Saint-Domingue and exported to it in turn. A fabulously wealthy plantation class arose, many of whom preferred to leave their properties in the care of managers and live extravagantly as absentee landlords in Paris.

"Slavery seemed eternal and the profits mounted," wrote James. "Never before, and perhaps never since, has the world seen anything proportionately so dazzling as the last years of pre-revolutionary [Saint-Domingue]." From 1783 to 1789 alone, economic output almost doubled.

Then came events that are all but unknown in the classrooms of North America, but that shook the world, transformed not only the Caribbean but the United States, and offered a beacon of freedom to the enslaved everywhere. When Parisians stormed the Bastille in 1789, the repercussions quickly reached Saint-Domingue. There, a tiny elite of white citizens, together with a somewhat larger group of Mulattoes (mixed-bloods) and free blacks who had economic but not political rights, lorded it over the mass of sullen and resentful blacks. A majority of those blacks had been born in Africa, since the average lifespan of a slave newly arrived on the plantations was less than five years, and tens of thousands of new captives had always to be imported. Terrorized, but without the acculturation to oppression of slaves born into families already enslaved, they were eager to rise up against their masters, white and Mulatto alike.

The result left the famous North Plain devastated -- indeed, one could say that Haiti has never really recovered from the blow. But it also marked the only successful slave revolt in history; abolished slavery for the first time in the western hemisphere; and (in 1804) established the world's first independent and enduring black-ruled republic. The international repercussions were dramatic. The Haitian war of independence bled France of some of its best soldiers, weakening Napoleon in his subsequent European campaigns. And with the jewel in France's colonial crown slipping from its grasp, the French had far less reason to hold on to their vast possessions on the North American mainland. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 ceded these in perpetuity to the United States.

Today, with Haiti virtually a byword for poverty and destitution, it seems hard to believe that the country could have once held such significance on the world stage. It is hardly, also, a country that most tourists or even plucky backpackers would consider visiting. But we spent nearly a month in the country, and found the experience revelatory and intensely moving.

There is no getting around the fact that Haiti is the hemisphere's poorest country. Port-au-Prince, the capital and home to some two million people, has one of the largest shantytowns in the world (Cité Soleil), and a particularly vile reputation for squalid conditions and urban mismanagement.

But the horror stories tell you nothing about the extraordinary street-life of the city -- more colourful than any I have ever seen. And they don't mention attractions like the Oloffson Hotel, a converted "gingerbread" mansion in the style that also graces New Orleans. Graham Greene set his novel about Haiti, The Comedians, at the Oloffson, which he called the Hotel Trianon. The place is now run by a young Haitian-American who fronts one of the country's most popular Voudou-inflected rock bands, RAM. Probably the most famous hotel in the Caribbean, it is a good choice for the visitor who wants to see something of Haitian urban life and not just a nice stretch of beach.

Nor does the stereotypical picture of Haiti prepare you for the reception an ordinary traveler might receive. We were welcomed everywhere, greeted by smiles and Creole "Bonjou"s in the street. Not once were we aggressively approached or molested. I include the three days we spent in Cap-Haïtien, Haiti's second-largest city (pop. 100,000). Large areas to the south of the city resemble the less desirable neighbourhoods of Calcutta, and definitely have a harder edge to them. We entered them only to catch local buses and tap-taps (the gaily-painted pickup trucks that are a public-transportation staple). But even in these grim, almost medieval slums, we did not encounter so much as a sharp word from a Haitian.

"O'Cap," as locals call it, was once Cap-François, seat of French colonial power in the Caribbean and a more flourishing entrepôt than Marseilles. Especially brutalized in the wars of independence, it has lapsed into torpor since. But it still features many dilapidated old façades along a Spanish-style grid that makes for easy navigation. At night, it is the darkest city I have ever encountered -- a flashlight is necessary for even a short walk down a main street, though the locals find their way without such assistance. But I walked around for hours in the evening, along streets sprinkled with Haitians socializing on their balconies and stoops. I have only agreeable incidents to report.

A taste of the wider reality of Haiti is a good idea for more adventurous visitors. We found it in Port-au-Prince and O'Cap, as well as in the little town of Jacmel (pop. 10,000) on Haiti's south coast. Once a thriving and strategic port, much fought-over in the independence wars, Jacmel today is a superficially sleepy town, but only if you don't arrive on a Carnival day -- every Sunday beginning on January 6th. We happened to arrive on precisely that day, entirely ignorant of what was planned, and found the place filled with revelers. In the evening, a flat-bed truck with a Haitian DJ aboard rolled down the street past our hotel, with about 1500 wildly-dancing Haitians in tow.

Norm, who bears a striking resemblance to Fidel Castro, made his career in Dallas, Texas, as a designer and vendor of women's clothing. He just happened to catch the wave of women's slacks, opened a chain of outlets, and was working and traveling almost around the clock. On his rare vacations, he would take Windjammer cruises to the Windward and Leeward islands of the Caribbean. One such cruise-ship broke down in Cap-Haïtien, stranding him there for three days. Something about the city captivated him, as it had me during my brief stay there. Norm said he returned to Dallas, looked in the mirror, and asked himself: "Why not?"

He sold the business and moved to O'Cap, where he lived for three years. On weekends he found himself spending more and more time in the beautiful coves around Labadie village, which looked out on a succession of majestic headlands disappearing into the distance.

Again he thought, Why not? He scouted out the then-overgrown ruins of the plantation once owned by a French colonial, wrecked when the blacks of the North Plain staged their massive uprising of August 1791. Much of the original masonry remained, though, and behind the main buildings was a kiln used to make a rough mortar in the days before cement. "It's the largest of its kind left in Haiti," he told me proudly. He led me through the photographic record of the restoration process, which used local materials carefully selected to match the foundations and remaining walls.

Ten years ago, Norm completed his own personal restoration, marrying Angelique. That sparked "the happiest years of my

life," he added contentedly. And no wonder. His elegant, personable wife has lent her design skills and knowledge of local

culture to the delightfully quirky arrangements of art, sculpture, and antiques that decorate the main house and bedrooms.

And he's living in a spot, and a dwelling, that must make any marriage seem like a permanent honeymoon.

Ten years ago, Norm completed his own personal restoration, marrying Angelique. That sparked "the happiest years of my

life," he added contentedly. And no wonder. His elegant, personable wife has lent her design skills and knowledge of local

culture to the delightfully quirky arrangements of art, sculpture, and antiques that decorate the main house and bedrooms.

And he's living in a spot, and a dwelling, that must make any marriage seem like a permanent honeymoon.

It certainly has impressed visitors who signed the guestbook. We scrolled through pages of the kind of language normally reserved for deities and magazine ads. "Like a beckoning light, the warmth and happiness you provided will never be forgotten" (Leamington, Ontario). "A special hideaway by the sea!" (Toronto). "One of the hidden treasures of Haiti!" (England). "Can I move in with you guys?" (American Embassy, Port-au-Prince). "The place is very beautiful, we have never seen something like this before" (the Netherlands). Miriam added her own encomium: "This place is like my dreams coming to life."

Giving foreign visitors a taste of life to the manner born presents logistical difficulties in Haiti. Norm found able staff in the adjacent village of Labadie, one of whom has been with him since the age of eight. (The couple is also on the verge of adopting three Haitian children, aged four, six, and fifteen, who will certainly liven up the environment.) He imported a sturdy generator, a necessity in a country where the power supply is sporadic at best. A satellite dish atop the kiln building draws in American TV channels; we spent a pleasant half an hour catching up on CNN Headline News.

Nonetheless, visitors expecting the full Club Med experience might be advised to look elsewhere. The showers are cold-water only (which we both found refreshing in the tropical heat). There are ceiling-fans but no air-conditioning. Aside from

Norm and Angelique's stimulating conversation, entertainment is in your own hands. Boats and guides, as mentioned, can

be hired for trips along the coast. The fantasy village of Plage Labadie can be visited on days when cruise-ships aren't in

port. And unlike so many resorts, Norm's isn't fenced off from the life outside it. The village of Labadie and the nearby

shoreline make for a pleasant stroll. The inhabitants are very friendly, and you can get a glimpse of ordinary life in a Haitian

rural community -- though one that is much more prosperous than most, with electrical lines, phones, and decent sanitation.

In the late afternoons, the local fishermen draw in their nets right from Norm's beach.

Nonetheless, visitors expecting the full Club Med experience might be advised to look elsewhere. The showers are cold-water only (which we both found refreshing in the tropical heat). There are ceiling-fans but no air-conditioning. Aside from

Norm and Angelique's stimulating conversation, entertainment is in your own hands. Boats and guides, as mentioned, can

be hired for trips along the coast. The fantasy village of Plage Labadie can be visited on days when cruise-ships aren't in

port. And unlike so many resorts, Norm's isn't fenced off from the life outside it. The village of Labadie and the nearby

shoreline make for a pleasant stroll. The inhabitants are very friendly, and you can get a glimpse of ordinary life in a Haitian

rural community -- though one that is much more prosperous than most, with electrical lines, phones, and decent sanitation.

In the late afternoons, the local fishermen draw in their nets right from Norm's beach.

I'll close with one anecdote that seemed to sum up the spirit of Norm's Place, and its owners. We felt the accommodations and food were a bargain, if not an outright steal. But Norm doesn't take credit cards -- the calls to Port-au-Prince for every verification proved too much of a hassle -- and our visit left us short of ready cash for the flight back to Port-au-Prince. Would we be able to secure a Visa cash advance in Cap-Haïtien, or would we encounter the same "communication problems" that had stymied us the last time we tried? If so, we'd be facing the cheaper option: a bone-shaking nine-hour bus ride along dismal roads to the capital.

No problem, said Norm. Pay me half now, save the rest of your cash for the flight, and mail me what you owe when you get back home. I'd hate for this to motivate anyone to take advantage of a generous and genial guy. But for us, it was the grace note capping a brief but unforgettable holiday.

Accommodation at one of the five double rooms at Norm's Place costs $25 per person per night. Optional breakfast, lunch, and dinner are $8, $10, and $12 respectively. Beverages are available; try Haiti's excellent Barbancourt rum (three- and five-star varieties). There are no service charges or taxes, but a small gratuity to the hotel staff is appreciated. Reservations are strongly recommended. Tel. 011-509-262-0400, fax 011-509-262-0866.

The hotel is at the edge of the small village of Labadie, where local youths offer boat-tours to other destinations and small islands dotting the coast. Labadie can be reached by local transportation (pickup truck and boat) from Cap-Haïtien. Daily scheduled air service exists from "Cap" direct to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, with Lynx Air (www.lynxair.com), which accepts major credit cards. Cap is also linked by air to Port-au-Prince several times daily. American Airlines, among others, connects Port-au-Prince to the outside world.

In Port-au-Prince, travelers can stay and eat at the upmarket Oloffson Hotel (tel. 011-509-223-4000 or 4102, fax 011-509-223-0919); for a different experience, try Hospice St. Joseph, tel. 011-509-245-6177, e-mail hsjpap@haitiworld.com). This Catholic-run facility is closely involved with local human-rights and health-care work, and offers accommodation with breakfast and dinner for $25 a day.

At Jacmel, about three hours by bus from Port-au-Prince, the Hotel de la Place on the central square (tel. 011-509-288-2832) offers decent accommodation and food. Ten kilometers outside town is a lovely cove and resort, Cyvadier Plage (tel. 011-509-288-2842), where accommodation with breakfast ranges from $38-60 a night.

Cap-Haïtien's best-known hotel is the Roi Christophe, once the colonial governor's mansion (tel. 011-509-262-0414). The central (grid) part of the city is ramshackle but attractive. Don't miss the Citadelle, a huge fort built by Haiti's post-independence rulers to guard against a renewed French invasion. Strategically set in the mountains about 25 kilometres from Cap-Haïtien, it is one of the most remarkable constructions of the 19th century, and lies close to the ruins of the Palace of Sans-Souci, built by the Haitian emperor Christophe and said in its day to rival Versailles.

All prices in this article are given in U.S. dollars, because that is the currency you will need in Haiti. It can be used in most hotels and for many tourist-type transactions, but you should also change some into Haitian gourdes (currently about 25 to the dollar). U.S. traveller's cheques are widely accepted, and cash advances on Visa and Mastercard are available from branches of Sogebank and Unibank, if the phone lines are working that day. Currency matters are a little more complicated than we can explore here; for more information, and a generally reliable guide to Haiti as a whole, see Lonely Planet's Dominican Republic & Haiti guidebook (Raincoast Books, 2002).

Haiti today is a very poor and sometimes-turbulent country. Be attentive to current events before you travel, and check U.S. government advisories. Good sources of up-to-date English-language information on Haitian politics and society are the Haitian Press Agency and Haiti Global Village. We encountered no violence or hostility walking around in Port-au-Prince and Cap-Haïtien, but muggings, armed robberies, and occasionally murders of foreigners are not unknown. Use caution, especially at night. As well, be careful to get people's permission before you photograph them; a dollar tip is standardly requested. No inoculations are required, but it is worth following a regimen of anti-malaria medication before, during, and after your trip. Tap water throughout the country is very far from potable, and only the local bottled waters, Culligan or Crystal, should be drunk or used to brush your teeth. Most of the better hotels will provide potable water free of charge.

For background on Haiti's colonial era and wars of independence, there is no better source than C.L.R. James's The Black Jacobins, first published in 1938 and still in print (Vintage Books). Useful works on the country's recent history include Amy Wilentz, The Rainy Season: Haiti after Duvalier (Touchstone Books, 1990); Alex Dupuy, Haiti in the New World Order (Westview Press, 1997); David Nicholls, From Dessalines to Duvalier: Race, Colour and National Independence in Haiti (Rutgers University Press); and Charles Arthur and Michael Dash, eds., Libète: A Haiti Anthology (Latin American Bureau, 1999). Of the novels set in Haiti, Graham Greene's The Comedians (Penguin Books, 1966) is probably the best-known.

The official language of Haiti is French, but only about ten percent of the population speaks it. Nearly everyone, by contrast, knows Creole. Apart from the ubiquitous "Hey you, give me one dollar," English is rarely spoken except by would-be tour guides -- a worthwhile option for those who wish to circumvent the language difficulties.

U.S. travellers require only a valid passport to visit Haiti, but for non-Haitian citizens, there is a $30 departure tax upon leaving ($10 if you go overland to the Dominican Republic).

-- Adam Jones

Created by Adam Jones. This article is copyright 2002. It can be freely distributed for non-commercial purposes if the author is credited and notified. For commercial use, please contact the author.

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

Blog: http://jonestream.blogspot.com

Last updated: 27 September 2002.