Alfred

George Jones, 1885-1949. The photo appears to have been taken shortly

after he signed up for service on the Western Front, in time for the Battle

of the Somme, July 1916.

Alfred

George Jones, 1885-1949. The photo appears to have been taken shortly

after he signed up for service on the Western Front, in time for the Battle

of the Somme, July 1916.

It was nothing special. Just a spent rifle bullet, curiously hooked at the tip, like a shark's tooth. I have no idea how it got there: probably it was left behind by a souvenir-collector who'd passed through the hotel before me.

It's even hard to say which war it came from. The bullet in my bed is an apt symbol for the modern history of Arras. Explosive violence lurks beneath the placid surface of the towns and villages of northern France. Twice in this century, armies have battled back and forth across the gently rolling landscape.

For a brief period in the early days of the First World War, the dividing line between the French and German forces ran right across Arras's central square. Today, that square - just outside the front door of my hotel - shows no sign of the fighting. A short walk away, though, the gloomy façade of the domed Arras Cathedral is still pocked and scarred by innumerable wayward shells and bullets.

There is something apocalyptic even in the quality of the early winter light. In Arras at this time of year, day doesn't exactly "break." Instead, darkness gives way to faint grey. A pale light puts up a brave struggle for a few hours, then gives up and retreats around four-thirty in the afternoon. The sun itself is rarely seen, except indirectly: lighting the fringes of clouds at dusk, or turning a jet's distant vapours into threads of spun gold.

The climate is appropriate. Time seems to hang in the air; seventy years might as well be yesterday. The impression is intensified by the scrupulous care with which 20th-century history is signposted.

For Canadians, Arras, holds a special significance. For most of the First World War, the Allies held the city. But just eight kilometres out of town is Vimy Ridge.

On April 9, 1917, the four divisions of the Canadian Corps launched their famous attack on this German front-line strongpoint. The operation was a spectacular success - in the context of a war where "success" was measured in yards gained. Here, as at most other points along the front, the German army held the strategic high ground. The Canadians not only overran the ridge but succeeded in holding it against a strong German counterattack.

In a wider sense, the Battle of Vimy Ridge was far from decisive. The Germans had already staged a planned withdrawal to a new, heavily fortified line, and the war still had a full year and a half to run before the Kaiser's armies collapsed amid the carnage and chaos.

Vimy has served, instead, as a symbol for Canada: the kind of bloody coming-of-age ritual that modern nation-states seem unable to do without.

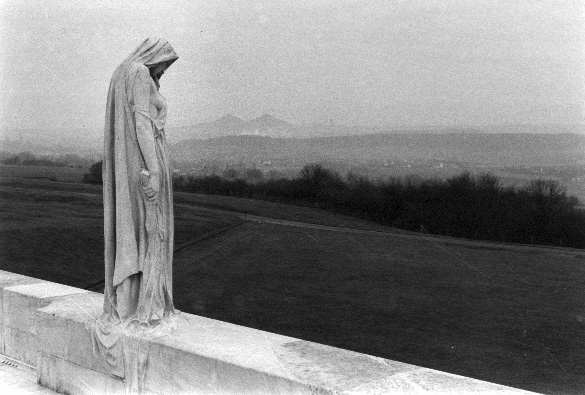

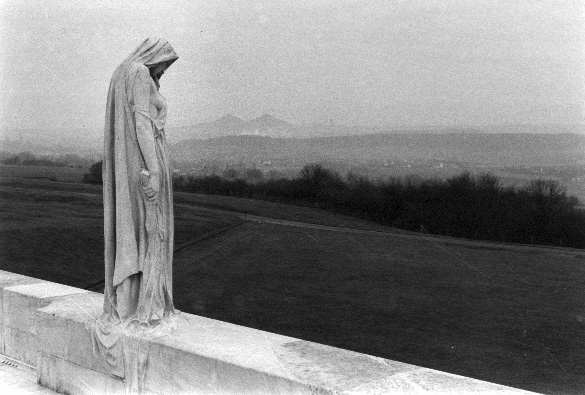

Vimy today is a haunted place. It has been turned into a park, deeded in perpetuity to the people of Canada. At the rear of the imposing monument to the 60,000 Canadian dead of the First World War, a statue of a crestfallen woman looks out from the summit of the ridge, over the plain beyond.

Today, the same countryside is dotted with smokestacks and industrial slagheaps. Far removed from the pastoral vision of the soldiers of 1917, perhaps. But the mutilated terrain over which the Canadians launched their attack has been preserved, and in parts even reconstructed.

There are other, more sinister reminders of the hell the soldiers left behind them. Signs off the main tracks, among the remnants of the trench system, warn of unexploded bombs and grenades.

For the amateur war historian, the Arras area offers a further bonus. Just half an hour away by train lies the town of Albert. This was the central staging point for the notorious, and disastrous, British attack in July 1916 that became known as the Battle of the Somme.

The opening day of the offensive, July 1, is famous as the "Black Day of the British Army." Owing to antiquated tactics and otherworldly optimism, the Allies suffered an almost inconceivable 57,470 casualties in a single day's fighting - including 20,000 killed.

For me, there is a personal connection. My grandfather, who died long before I was born, fought with the British at the Somme. He was blown up and buried by a German shell in no man's land. Three days later a search party, by some astonishing chance, found him under the earth, unconscious but still alive. He recovered. According to my father, it was an experience he didn't talk about much.

I walked out of Albert in the footsteps of my grandfather and the countless troops who headed for the front to mount the Somme offensive. Still standing in the heart of Albert is the famous basilica, topped by a gilded statue of the Virgin Mary holding aloft the Christ child. In the Great War, the basilica was badly damaged by German shellfire, but the statue clung to the steeple throughout the German bombardment. It became a good-luck symbol for the Allied forces, and its precarious hold was soon strengthened (surreptitiously) by teams of Royal Engineers, who recognized its importance to troop morale.

It is a disquieting sensation to stroll across the terrain for which so many thousands fought and died. I stood for a while on the lip of the Lochnager Mine Crater, a couple of kilometres outside Albert, near the village of La Boisselle. The Lochnager Mine was the largest of a series detonated under German lines to start the Somme offensive. It left behind an awesome bowl in the earth, as though a meteorite had struck. After the war, the land was purchased as a testament to the crater's role as a place of refuge for the numerous troops who spent July 1 pinned down by German machine guns. You can see the hill-line from which British forces attacked at dawn, walking at a rigid parade-ground pace into the steel hail of the German machine-gunners.

A memorial at nearby Thiepval commemorates some 70,000 British soldiers who went missing over the four-and-a-half months of the "battle." The Allies suffered 630,000 casualties in those few months, but never penetrated more than eight kilometres behind German lines.

Newfoundlanders, who were at that time citizens of a separate crown colony, have a special link to the Somme. A few kilometres along the road from Albert to the village of Beaumont Hamel lies the Newfoundland Memorial Park. Here, under the eye of a bronze caribou, is the ground the Newfoundland battalion crossed as it launched its part of the July 1 offensive. The attack turned into a massacre, and the Newfoundlanders suffered one of the most withering casualty rates of that whole horrifying day.

The terrain is even better preserved than at Vimy, and more haunting. The front-line trenches are clearly marked. You can stand on the German parapets and imagine the waves of Newfoundlanders stumbling across a hundred metres of barbed wire and corpse-strewn earth.

Beaumont Hamel was their objective - today, just a short walk from the Memorial park, down a muddy farmer's path. The village was not taken until November 1916, by the 51st (Highland) Division; the 51st's battle fatalities were buried in a large shell-hole, which is now a cemetery at the far end of the park.

When I visited, the Somme farmers were waiting for the spring plowing. If past years are any indication, that plowing would probably turn over more relics of the Somme offensive: spent (or unexploded) shells, helmets, insignias. Almost certainly, too, a few more old bones from no man's land would percolate to the surface. As in the past, they would be disinterred and moved to graves in one of the dozens of cemeteries in the area, under headstones reading: "A soldier of the Great War ... known to God."

Created by Adam Jones, 1998. No copyright claimed for non-commercial use of text or images if author

is acknowledged and notified.

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

Blog: http://jonestream.blogspot.com

Last updated: 10 October 2000.