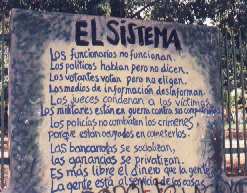

Managua, 1996 (Photo by Karen Stille).

Wall outside the University of Central America,

Managua, 1996 (Photo by Karen Stille).

The System

"The functionaries don't function.

The politicians talk, but they don't say anything.

The voters vote but don't elect anybody.

The information media are agents of disinformation.

The judges condemn the victims.

The soldiers are in a war against their compatriots.

The police don't fight crime,

Because they're too busy committing it.

Bankruptcies are socialized,

Profits are privatized.

Money is more free than people.

People are at the service of things."

- Eduardo Galeano

In Costa Rica, people wrinkled their noses at the sound of the word. "Feo Nicaragua," they sniffed. "An ugly place."

To which I can only respond: You'd be ugly, too, if you'd been tortured for the better part of a half-century.

Sure enough, crossing the Nicaraguan border at Peñas Blancas was a little like stepping back 75 years in time. Ox-drawn carts with wooden wheels are à la mode in the rugged cattle-country of southern Nicaragua. Poor-as-shit thatched-roof huts crowd the roadside. The market at the town of Rivas reminded me of a scene from the movie Walker - which was filmed there, sure, but was set in the 19th century.

I exaggerate, of course. The surprise, returning to Nicaragua after five years, is to see anything functioning. But buses still run; it is even possible to find a seat on the Canadian Blue Bird bus ("Your Children's SAFETY is our business") which takes me into the Nicaraguan capital. Pulling into Managua, I am met by a familiar big-city bustle at the Huembes market. Taxis screech in and out of the parking lot, and traffic roars over the main road's concrete paving stones - the very ones which were torn up for barricades in the 1979 revolution, and again in the massive strike and near-insurrection of last July.

The water still flows - in Managua, it's even drinkable - although it's still shut off twice a week at least, more often at the height of the dry season. Electrical blackouts are more rare. Public transit is operational. Private cars still rattle around the streets, although the only requirements seem to be four wheels and an engine: windshields, tire-treads, even license-plates are all optional. In an almost surreal fashion, life goes on, in a manner which can only strike a North American as unusually relaxed and laid-back. Managua is not Nicaragua, but the city is, nonetheless, a survivor: ravaged by economic and social dislocation, but hanging in there.

Politics is as inescapable as ever. On the bus in from the border, it is gratifying, even a little exhilarating, to see visible evidence of Sandinismo everywhere, and mostly unmolested. People on the bus plough through their copies of Barricada, the Sandinista paper. Many of them wear their bright "Daniel" T-shirts from the 1990 elections - though with basic goods like clothing in short supply, this can't necessarily be interpreted as a statement of Sandinista sympathies. From one of the rural thatched huts, a huge red-and-black Sandinista banner billows proudly in the breeze.

However they may have fared in the elections themselves, the Sandinistas clearly won the pre-vote graffiti war hands down. The sloganeering and artwork is ubiquitous. Very little of it, surprisingly, has been disfigured by the election's eventual victors.

Satisfying as some of us might have found it to see Señor Bermúdez sent to hell, there to roast in peace alongside his fat friend Somoza, the assassination was a near-catastrophe for the tenuous peace hammered out between Nicaragua's contending social forces in the concertación agreements of July 1990.

Given that Bermúdez had headed the terrorist force which sought their overthrow, suspicion immediately fell on the Sandinistas. Rather, it was dumped there by a Nicaraguan ultra-right hollering for revenge.

The Sandinista representatives in the National Assembly resolutely refused to stand for a minute's silence in Bermúdez's memory, but they were quick to deny any involvement in his death. The FSLN, said ex-Vice Preside Sergio Ramírez, had "always rejected political assassination and terrorist actions. In the clearest possible terms, we reject these tactics, wherever they may originate."

Ramírez added, in a cautionary tone: "Those who see in this act the opportunity to initiate a violent escalation, as indicated by the irresponsible way in which they are seeking to justify acts of irrational vengeance, must be stopped - because a spiral of killings will be unstoppable."

The radio airwaves were filled with the voices of political leaders from the FSLN and Violeta Chamorro's governing UNO coalition, appealing for calm, promising a prompt and exhaustive investigation of the killing. Over the following days, discussion in the Sandinista and pro-Sandinista press centered on the factional infighting among the ranks of ex-Contra leaders, many of whom were vying to organize the increasingly disaffected ranks of demobilized Contra foot-soldiers, diffused throughout Nicaragua. Bermúdez had headed one of three broad Contra factions. It was the opinion of many that one of the other groups had bumped him off.

By the end of the week, the situation had calmed considerably. A week after that - as the investigation proceeded, and one hapless suspect was incarcerated, then released - the story had all but disappeared from the newspapers.

Fires were still burning in the U.S., however, where Bermúdez had been a favorite son of the far right. Reagan's former ambassador to the U.N., Jeane Kirkpatrick, wrote a column accusing the Sandinistas of complicity in the Bermúdez execution. According to Kirkpatrick, rumors were circulating that "one of the groups of armed civilians" under Sandinista direction had carried out the killing. She pointed a finger in particular at General Humberto Ortega, chief of the EPS (Sandinista People's Army), who was retained by Chamorro's government to oversee the progressive dismantling of the Sandinista military apparatus. The new UNO government, Kirkpatrick claimed, was handcuffed by continuing Sandinista domination of the Army and security forces. The Sandinistas' "control over these institutions contributes to disorder," she complained; hence the lackadaisal investigation of Bermúdez's death.

Kirkpatrick's article was published in the Chamorro-owned daily paper, La Prensa, on March 4. Alongside it appeared a carefully modulated but scathing response - headlined, "Disinformation" - by Antonio Lacayo, President Chamorro's chief minister. With perhaps a touch of irony, Lacayo complimented Kirkpatrick for not having forgotten Nicaragua, "unlike so many others." But he pointed out that Bermúdez, since his return, had gone about his business with so little fear that he was not even accompanied by a bodyguard on the night of his death. The fact that the crime was still unsolved nine days later, when Kirkpatrick wrote her column, "hardly constitutes a justification for concluding that there exists an official indifference," Lacayo commented.

Crises have a short life in Nicaragua. There is always another one looming on the horizon, preparing to crowd out its predecessor. But this by itself can't explain why the Bermúdez killing dropped so quickly from public view. Equally significant is the fact that neither UNO nor the Sandinistas had any interest in a round of destabilizing mud-slinging, just as it was in neither's interest to assassinate Bermúdez in the first place. More revealing, perhaps, was the immediate aftermath of the killing. La Prensa reported that "hundreds" of Bermúdez supporters lined the approaches to Sandino Airport, shouting "Death to the Sandinistas!" as Bermúdez's corpse was delivered for its journey to Miami. When the coffin arrived in Florida, on the other hand, "thousands" were waiting to receive it - up to a hundred thousand supporters, by one report.

The old Contra chief, it seems, had spent so much of his time relaxing in Miami on his CIA stipend, courting the exile crowd, that the great majority of his fans were there. They remain vocal enough, but they're hardly a decisive factor in the Nicaraguan political equation.

On the day I arrive in Managua, my father, along for the ride for a couple of days, tracks down the friend of a friend who has recently returned after six years of self-imposed exile in Florida. We are duly invited out to her gracious home on the Carretera Masaya for rum, shrimps served in an exquisite spicy sauce, and a chance to meet the family.

Señora J.'s husband had stayed behind in Nicaragua to manage a large industrial enterprise, while she and the kids flew north. Every inch the hostess - making light conversation in reasonable English, and smiling encouragingly at my bad Spanish - she turns very serious and steely indeed when the conversation touches on politics.

I ask her about Bermúdez. She had met him, it turns out, at a Contra fundraiser in Miami. "He was a very great man. Of course, the Sandinistas killed him. He was too popular with the people, and they saw him as a threat. All the people loved him."

Were acts of revenge likely? She is convinced yes, and the names roll off her tongue with real relish: "Daniel or Humberto Ortega. Tomás Borge. One of them."

Señora J. had stuck it out in Nicaragua through to 1984, even though, she says, she feared for her life. "You know, I'm a direct woman, I speak my mind. I thought the Sandinistas would come and kill me for it, like they killed so many people who spoke out. I'm surprised they didn't."

Were things, at least, an improvement under the Sandinistas, compared to the Somoza dictatorship? Señora J. mulls that over. "Well. I hated Somoza. What I didn't realize at the time was that the Sandinistas were committing all kinds of atrocities and blaming them on Somoza. So I came to blame him for those things, even though he was in no way responsible. Under Somoza, you can't deny it, Nicaragua was the best, the richest country in Central America."

Her greatest venom, though, is reserved for the new government. For those like Señora J. who equated a Sandinista electoral defeat with the complete dismantling of the Sandinista state - a return to "Somocismo without Somoza" - the Violeta Chamorro administration has been a bitter disappointment. Chamorro retained Sandinistas in key positions of authority; she approved negotiations with Sandinista-linked unions during the two dangerous strikes of Summer 1990.

Last November, during an outbreak of right-wing agitation, Chief Minister Lacayo pointedly proclaimed that "In Nicaragua there was not an armed victory, and the counterrevolution did not triumph." Instead, "There was an electoral process, a victory that obliges us to choose democracy, reconciliation and concertación." Meanwhile, the darling of the Nicaraguan far right, Vice-President Virgilio Godoy, was virtually frozen out of office by the President and her close advisors. Godoy was reduced to slinging arrows at the administration of which he was officially second-in-command. (On February 25, the first anniversary of the UNO victory, he conveniently arranged to be out of the country.)

It's not surprising, then, that Señora J. tells me: "This government has been Sandinized. Violeta is a woman without a brain, and her advisors are all in league with the Sandinistas."

What about Godoy? She smiles broadly. "A very good man. Not left, not right. Moderate."

The Sandinistas, while badly damaged by the electoral result of February 1990, still emerged with a respectable 41 percent of the popular vote. I ask Señora J., if figures like Godoy and Bermúdez are so beloved, what is the Sandinistas' constituency? Who supports them?

She misunderstands the question, or maybe she doesn't. "Saddam Hussein. Khaddafi. That's about it."

After a while the conversation turns to the tour my father and I have taken of downtown Managua. In fact, of course, there is no downtown. The city was knocked flat by the earthquake of December 1972, and was never rebuilt. The dictator Somoza bought up large tracts on the city's outskirts, then gave preferential treatment to applications for building permits in the areas he all but owned. The result, today, is a city that lives and bustles along its periphery: nodes of commercial activity and suburban neighborhoods are strung around the outskirts. Downtown is the Bank of America, the Central Bank building, and the Hotel Intercontinental - the only major edifices to survive the quake - and a vast, eerie expanse of dusty, overgrown lots, strewn with débris. The area is popularly known as los escombros: "The Rubble."

Many of the lots are crammed full of squalid squatter's shacks, made of castaway wood, tin, and cardboard. Recently, the bulldozers of the Managua municipal authorities have been busy in the squatter settlements, mowing down the makeshift shacks. City workers follow behind, erecting shiny new barbed-wire fences around the lots. Apparently someone, somewhere, has a development plan for the downtown core. Perhaps that plan will never leave the fevered mind of Managua's virulently anti-Sandinista mayor, Arnoldo Alemán.

I ask Señora J. about that sea of squatter shacks. "Housing is a big problem, sure," she agrees. "But what can you do? You can't just let all these people come in from the countryside and set themselves up in the middle of downtown. It's a terrible eyesore. And you know, they tap into the water mains and take water for themselves without paying for it. So sometimes all the water gets used and we don't have any out here!

"There's plenty of land in the northern part of the country," she continues. "It's just going to waste because these people don't want to work it. They should be moved back there so we can get this city cleaned up."

There is a strange expression on her face, and after a minute I put my finger on it: She is embarrassed. The Managua of her mind's eye is a jewel; the Managua we have seen on our tour of "downtown" is a festering sore. It is as though we have been invited into her kitchen, only to find it crawling with cockroaches.

Throughout most of the conversation, Señora J.'s husband sits in benign silence. His occasional comments make it clear that he understands more of the English banter than he's letting on. In a subtle way, I sense he does not fully share his wife's extravagant hatred of the Sandinistas. He has, after all, spent his time here, and the company for which he works survived and prospered under the revolutionary government.

The two grown children, Kathy and Carlos, float in and out. Carlos is in the government, but he's cagey about his exact function. Kathy, who's divorced, smokes a lot and adopts a pose of terminal boredom. Her son, Nestor, is blond-haired, bucktoothed nine-year-old who's studying at the American School in Managua. I ask him if he has a girlfriend yet - the kind of question guaranteed to make nine-year-olds blush and adults smile.

"Yeah, I have a girlfriend. But my grandfather wants me to marry a nigger." He screws up his face in disgust.

That stops things cold. Even Señora J. seems faintly ill at ease.

"Why wouldn't you want to marry a black person, Nestor?"

"Niggers stink," Nestor explains.

As a going-away present, we are loaded down with bottles of excellent Flor de Caña rum. Kathy drives us back, chewing gum, smoking nervously. "I love Miami," she says. "It's the best. It was my own decision to return to Nica, but now I want to go back. I have to find myself a nice Latino guy there to marry, I guess."

Frances is my age - 27 - tall, wiry, and African in appearance (her father is Afro-Caribbean, from Nicaragua's Atlantic Coast). One evening, a few weeks after I meet her for the first time, we are lying in hammocks on a cool, breezy Managua evening, watching the stars. I get her talking about herself. In 1979, she was in León, and fought her way into Managua with the Sandinista columns. Somewhere along the way, she was wounded. Matter-of-factly, she hikes up her T-shirt to show the tangle of scars on her belly. "This is where the bullet went in, and here" - she turns a little - "is where it existed." Did she, herself, kill anyone? "Sure. But never in cold blood," she adds hastily, as if to reassure me I have nothing to fear.

"When I fought, it was for this country and for the liberty of my people," Frances says in the same offhand, casual tone. "I'm a Sandinista militant, but I wasn't fighting for an insignia, whether of the FSLN or anyone else." Today she works at Telcor, the Nicarguan Post and Telecommunications Ministry. She makes just enough to get by. "It's surviving. It's not living." She wrinkles her nose and shrugs resignedly.

Frances is a survivor of the '72 earthquake. She describes the event with energetic gestures: walls falling in, houses swaying and collapsing, streets crumbling into the muddy mire of subterranean groundwater. That gets her talking, with great gusto, about all the natural catastrophes to which Managua residents are prone - particularly, she suggests, those of us in the pleasant, middle-class suburb of Colonia Centroamérica. "If there's another earthquake, boom, goodbye. See these walls? They're concrete, not stone blocks. Be down on you in an instant and splat, you're dead. Did you know we're just a couple of kilometers from the Masaya volcano? If it ever erupts we'll be under lava in a flash." I nod my head, thinking of my return flight, hoping Managua's Armageddon holds off until then.

"But don't worry about any of that," Frances says soothingly. "I don't worry about it at all. When my day's up, it's up. Nacimos para morir - we're born to die."

One evening, Frances comes home after hours of drinking with a friend, Alberto, who fought in Managua and Masaya during the insurrection and spent five years in the madness of the northern mountains, battling Contras. Alberto is 28. We chat about this and that. After he leaves, Frances slips next door to buy a bottle of beer, comes back, rolls us a fat joint. She is already inebriated and getting more so.

She starts talking, again, abut the insurrection. "I don't know how many people I killed. I mean, you're running around, ducking behind barricades, firing in the general direction of something, ducking again. You never know. But I only killed once in cold blood."

That's a change from what she'd assured me earlier. "When? Who?"

She sighs. "Four months after the triumph. A Somocista military man who was responsible for the deaths of many, many of us. He'd fled Managua and was holed up in Puerto Sandino. We tracked him down. Three of us, the squad that killed him. With AKs" - the ubiquitous Soviet- and Chinese-made machine guns - "brap, brap, brap. Shit, it's a bad thing, to kill like that. I never want to do it again. Triste. Triste. Sad."

I calculate backwards: she was sixteen at the time.

She looks at me strangely. "Ah, you see me, you talk with me. But you can't know. Sometimes it's like ... my home isn't here. My thoughts are ..." She trails off and twirls a finger in the air at the side of her head. She points at the half-drained bottle of beer. "Too much of this stuff, you know. For the pain."

Her boyfriend was killed in the mountains years ago, she says. She is estranged from her mother on political grounds. At the moment she is seeing a young German woman doing graduate research in Managua. "Just now and then, I need to be held." It is a straightforward statement: she wants, and expects, no sympathy.

Later, almost nodding off from the booze and dope, she tells me she's planning to jump on a ship and head to Kuwait. She wants to find work in the postwar reconstruction there. The application procedure cost her a quarter of her monthly income, but she figures it's worth the gamble. "I want to spend two or three years overseas. See some of the world. I don't want to be here anymore."

A good question. A few days earlier, around midweek, Managua had erupted with rumours about an impending devaluation of the national currency, the córdoba. Government sources confirmed a devaluation was at hand. It would be aimed at finally phasing out the nearly worthless old cordoba and phasing in the new "gold córdoba," which had been introduced shortly after the Chamorro régime took power, with an artificial one-to-one parity with the U.S. dollar. The idea, the governmented sources suggested, was to devalue the gold córdoba relative to the dollar. Its exchange rate would then be fixed relative to the old córdoba, which now stood at 4,500,000 to the dollar and was still hyperinflating wildly. The old cordoba could then be dispensed with, and the shiny new gold cordoba would stand as the country's only currency. Prosperity and foreign investment was bound to follow.

No-one, on this Saturday, has any idea what the scale of the devaluation will be. Estimates range as high as 100 percent - that is, slashing the dollar exchange rate of the gold córdoba in half. The pervasive uncertainty has meant that for two or three days, commerce in Managua has all but ceased. How can merchants be sure that they won't sell goods at retail for prices that, once the devaluation is made known, turn out to be less they paid wholesale?

The few commodities still up for grabs are fluctuating wildly in price. The "coyotes" - those bands of hardy entrepreneurs who crowd Managua intersections, proffering dollars and gold córdobas at at exchange rates about 20 percent higher than the banks - are hedging their bets. Yesterday, before the rumours started, you could buy dollars for around five million old córdobas. Today they cost 12 million.

The gold córdoba, meanwhile, has inflated to 1.4 to the dollar on the street exchange. This proves to be a brief boon for shoppers at Managua's official diplotienda, the hard-currency store where the gold córdoba is still pegged at one-to-one with the dollar. On Friday, swamped by bargain-hunters, the dollar-store shuts down too: "Closed for Inventory," like every supermarket in town. On Saturday, I wander the streets for an hour trying to find something to eat. Eventually I come across a roadside café selling rice, beans, and a scrap of meat. It costs four dollars a plate at the official exchange rate, more than twice its price 48 hours earlier.

On Sunday the news breaks, courtesy of a four-page "special edition" of La Prensa. The devaluation will be - not one hundred, not two hundred, but five hundred percent.

Literally in the blink of an eye, the official exchange rate for the old cordoba leaps from 4.2 million to 25 million to the dollar. The gold córdoba slips to five to the dollar. Public sector wages rise by only two-and-a-half times, on average; wage increases in the private sector are at the discretion of the owner. Government-controlled prices of staple goods increase by factors of three to five.

The measures, Violeta Chamorro announces in a speech to the nation, are aimed at "turning economic disaster into stability," stemming hyperinflation, and making sure that "workers' salaries maintain their purchasing power for the necessities of home and hearth." ("Home and hearth" is a big catch-phrase for her tradition-conscious administration. Never mind that "purchasing power" has just been slashed by 30 to 50 percent - for those lucky enough to have their wage increases mandated by the public sector.) The measures, Chamorro concedes, are strong medicine, but "Vale la pena" - it's worth the pain. (Vale la pena immediately becomes the slogan for the new austerity campaign, appearing in newspaper ads alongside photos of a stalwart-looking Violeta.)

The outcry from Sandinista ranks is loud and strong. But the government has timed its measures well. The devaluation is so enormous that most Nicaraguans are simply dazed, immersed in the immediate problem of figuring out the ramifications for their daily lives and businesses. People who until now have scraped by with the bare necessities are reduced to the most basic subsistence, if that. Juan José Villalta, a pensioner, tells Barricada that his pension has been raised to 168 gold córdobas a month. "A tortilla costs a million and a half," he says sadly. "I eat three tortillas a day."

But the only alternatives to the measures - rebellion or general strike - are just not on the agenda in Nicaragua. Memories are still fresh of the two massive strikes of Summer 1990 which brought the country to the brink of civil war. In Managua last July, barricades sprang up all over the city; armed "squads of national liberation" were organized by the right wing; Sandinista militants made night-time rounds among sympathizers, urging them to stockpile weapons in their bedroom closets. The experience was exhilarating for some, but chilling for many others. After ten years of grim, exhausting war, very few Nicaraguans really want to come that close to the precipice again.

The 1990 strikes were widely hailed as Sandinista victories. The FSLN successfully mediated negotiations between the government and the main union, the FNT. In retrospect, though, the balance-sheet seems more ambiguous.

"To be perfectly honest, it was a pain in the ass trying to get around the city," one Managua resident, a Sandinista, tells me. "Not only during the strike, but for a long time afterward, since the roads were in such a mess. And it was scary. I was there when hundreds of anti-strike people came pouring into Managua. A lot of them were carrying sticks, and I saw at least one gun. They were shouting, 'We want to work!' A lot of them were market people from nearby cities. Their livelihoods were being threatened because the barricades stopped them getting into Managua to sell their wares.

"I guess the workers - the FNT and the Sandinistas - proved that no government program could be imposed without their assent," she concedes. "But you know, the reason they struck in July was that the government wasn't keeping the promises it had made in May. And all they ended up getting the second time round was more promises, more pieces of paper. The government hasn't lived up to any of those commitments, either. So what did they really achieve?

"There's a lot of people here - and I know some of them, very strong and devoted Sandinistas - who say, 'We just want to live our lives. We don't want war, we want to be able to work and make a decent living. We don't want to run out into the street and demonstrate every five minutes.' People are tired, man. This has been going on a long time."

If this kind of thinking predominates among Nicaraguans - at least in the cities, where any immediate threat of insurrection would arise - it could explain the tacit grace period the Chamorro government receives after the devaluation announcement. The Sandinistas issue a formal position paper on the party's views "in face of the national problem." Eloquent and humane, it acknowledges the necessity of stemming hyperinflation, but calls for the "urgent implementation of auxiliary actions to benefit the least protected sectors of the population," including food assistance for the poor and provision of essential medicines. It is, the FSLN cautions, "a critical moment for the country."

The critical moment passes. The government settles a protracted strike by hospital workers, recognizing them as a "historically underpaid" sector and granting them wage increases which, almost uniquely among public-sector employees, keep pace with price increases. Meanwhile, the government - whose top executives are paid in dollars, granting them immunity from the impact of their own measures - sets its sights on the end of April. By then, the old córdoba will be history; hyperinflation will be in full retreat; accords will be reached with international donors and lending agencies, and stabilization will be well underway. That, at least, is the dream.

Still and all, the scale of the austerity measures astonishes me. When they are first announced, I expect any minute to hear the grating sounds of paving stones being torn up for barricades. The day after the package is introduced, I drop by the home of Scott Eavenson. Scott translated for the Tools for Peace delegation on my first trip to Nicaragua. Now he is married to a Nicaraguan woman and living just down the road in Centroamérica. He's trying to make ends meet, with his tour-group and delegation clientele radically reduced in the wake of the Sandinista electoral defeat.

"Just how far does the government think it can push people?" I ask Scott, more or less rhetorically. "I mean, the workers were at the margins of subsistence before the crunch hit."

Scott shrugs. "That's what I thought when I first arrived here. That the next round of austerity measures would be the straw that broke the camel's back."

"When was that?"

"Nineteen eighty-three."

The first fact of life is that anybody who can possibly sell something is doing so. The family down the street with a refrigerator is retailing ice and cheese through its front door and window grill. The house kitty-corner to me has a phone; its occupants rent it out for the exorbitant sum of two gold córdobas (about 40 cents) a call. (There are, of course, no public phones in this part of the world, and the directory for the entire country would fill about a quarter of the Vancouver phone book.)

The family next door is strategically located on the corner of the row. Through a door which opens onto a busy alley, it has set up a flourishing trade in packets of soup, tinned goods, rum, and beer. In the afternoon, the front step of their little tienda becomes a neighborhood pub: a hangout for a small knot of steady customers (who usually leave rather less steady). Nearby is another house that serves as the local milk-and-egg outlet. The owner has outfitted his living room with racks of Ropa americana, the second-hand clothes shipped in bulk and retailed throughout Central America at prices that would make the Salvation Army blush, but which are still cheaper than buying new.

Mornings and afternoons, I sit on my front step and watch the regular stream of women wandering down the callejón, performing amazing balancing acts with wicker baskets on their heads, laden down with vegetables and snacks and tortillas. They call out their sales pitches in penetrating, sing-song cadences. Newspaper boys and shoeshine men make the rounds. Occasionally a small kid follows in their wake, begging door-to-door for food or money.

Garbage collection in Managua is almost nonexistent. The standard practice is for rubbish to be lugged to one of the 150 unofficial dumpsites scattered around Managua. This offers more room for entrepreneurial activity. Into the gap steps a wizened old man in filthy polyester slacks. He comes around every few days and, for a couple of dollars or a pound of rice, will cart away the bags of litter and dead leaves you've been allowing to pile up in your courtyard. We are lucky to have an official garbage collection point just down the road - big iron barrels with "Municipality of Managua" stencilled on the side - but it doesn't seem to help much. Ordinarily, the barrels are stuffed to bursting. If the collection trucks haven't been by recently and aren't expected anytime soon, which is usually the case, the barrels are simply tipped over. Their contents spill into the parking lot; the sticky, rotting mess is then set alight. A sickly sweet smell wafts around the neighbourhood, and the fire smoulders for days.

When I first move into Colonia Centroamérica, the commercial and entrepreneurial life just below the surface is almost invisible to me. Getting to know the area means wandering around with my eyes peeled for the nondescript signs on houses, announcing whatever is for sale as the family's sideline, and (most important) making inquiries of those who've been around long enough to have up-to-date mental maps of the local network.

Now more than ever, Managua gets through the day by word-of-mouth, on the basis of a subtle skein of common points of reference. This is, after all, a city where formal addresses barely exist: street directions are often based on where certain landmarks used to be - before the earthquake, before the Revolution. At first I am perplexed by how much of the Sandinistas' physical legacy in Managua has been left intact. One would expect a campaign of despoliation to be mounted not only by the new city authorities, but by the more extreme, unofficial rightwing elements who are not bound by niceties of inter-party diplomacy. Surely they'd like to see the revolutionary landmarks - monuments, commemorative plaques, and so on - obliterated from the landscape?

Then again, I muse, the answer to the riddle might be more practical than political: no-one could find their way around town without them.

It would be nice to be able to sketch a profile of the Sandinista Front and the revolutionary movement as they now stand in Nicaragua. But my evidence is too fragmentary; the Managua circle I moved in, too constricted. And witnesses with return tickets should be wary of drawing sweeping, presumptuous conclusions about complex situations which they can only glimpse, not truly live.

Instead, I want to present four Sandinistas to you - two of them in this issue, two of them next time. Wherever possible, I want to let them speak for themselves.

All four are urban, middle- or upper-class militants who hold important positions in the Sandinista and pro-Sandinista media. (I was in Nicaragua to study the transition of the Sandinista press since the 1990 election defeat, and these people were at the top of my list of interview subjects.) As a result, although three of the four are recognized (or self-proclaimed) champions of Nicaragua's poor and disenfranchised majority, none can provide testimonies from the countryside, where members of pro-Sandinista agricultural cooperatives are struggling to defend their land from incursions by old landlords and demobilized Contra rebels - or, in some cases, working to forge alliances with those same ex-Contras on issues of common concern. None of the people profiled below can tell you what it's like to live on Nicaragua's Atlantic Coast, as the legacy of autonomy from the Sandinista years (which was, admittedly, very late in arriving) is chipped away by the Chamorro government. And they don't have stories from the urban front lines - where Nicaraguan women and men struggle to eke out a bare living, as their meagre incomes are eroded by inflation or government austerity plans.

What these voices can provide, perhaps, is some indication of the different currents now flowing through the Sandinista movement, and the various controversies over identity and strategy that have raged among Nicaraguan revolutionaries since the Sandinistas surrendered the reins of government.

Information about the Sandinistas' first Congress, held July 19-21, is scarce in the North American media, even in the progressive press. What details there are, though, suggest that the formal structure of the Sandinista Front, and the relationship between leaders and the rank-and-file, has not been radically altered. The existing National Directorate has been supplemented by two more members (to replace Carlos Nuñez, who died in 1990, and Humberto Ortega, who resigned his post in order to remain head of the Army under the Chamorro government). All the surviving members of the old directorate received a somewhat gerrymandered vote of confidence (they were presented to delegates as a blanket slate of candidates). And the nine-man directorate is still a nine-man directorate - both new additions were male. Apparently the "glass ceiling" blocking women's rise to the top is every bit as daunting an obstacle in Nicaragua as it is in North America.

The most significant change in the direction of greater inter-party democratization is the decision to redefine the role of the Sandinista Assembly, previously a consultative body subordinated to the National Directorate. The Assembly will now have formal sovereignty over the directorate, and will serve as something of a "parliament" for discussion and deliberation. How this relationship will work in practice remains to be seen.

The overall impression is of a stopgap Congress: one designed to retain much of the old structure (perhaps to preserve a measure of institutional stability in the face of serious internal upheaval), while still making some attempt to respond to the rank-and-file clamour for new faces and more democratic decision-making. As revolutionary Nicaraguans face the future, then, there can be little doubt that the issues and disagreements outlined in the following profiles will remain live ones.

The weapon tells you that underneath his laconic demeanour, William Grigsby is edgy. One senses that he's usually a little agitated: Grigsby is, after all, probably the most controversial voice on the airwaves, a longtime Sandinista militant who offends other Sandinistas every bit as much as he ruffles right-wing feathers. Any added nervousness might be due to the timing of our interview. We're speaking a week and a half after the assassination in Managua of Enrique Bermúdez, former military chief of the Contras (see Part One of the "Notebook" in the May/June Connexions). The day Bermúdez was killed, Grigsby tells me, "we had death-threats all day long." They weren't the first such threats, and according to Grigsby, they come at him "from all sides."

He's a very gringo-looking man, as his name would suggest: pale complexion and blond hair. His leg jitters and twitches as he answers questions in short, sometimes curt bursts. Grigsby is 31, a self-trained journalist with only a high-school education. After the Revolution, he became a founding member of the New Nicaragua Press Agency (ANN) and hosted a program on Sandinista Television. He did a stint in the Sandinista Front's Department of Agitation and Propaganda. In 1986 he started work at the Managua daily El Nuevo Diario, and was also taken on by a pro-Sandinista radio station, La Primerísima.

On February 5, 1987, an article commissioned by Grigsby appeared in El Nuevo Diario. It was an interview with Alan Bolt, leader of a Matagalpa-based theatre group. Bolt, an early Sandinista militant, had an ideological falling out with the Front's leadership; he was given his walking papers in 1976. What he had to say to El Nuevo Diario was explosive. He criticized the Front's verticalism and bureaucratism, and issued a call for a more horizontal apportioning of power: for "discipline without hierarchy ... well-being for all, but without special privileges."

The criticisms were close to Grigsby's own, which were well-known by that point. It was too much for the Front's leaders. In January 1987, Grigsby was expelled from Sandinista ranks. He subsequently wrote an article of his own for El Nuevo Diario entitled, "Fear of Democracy." The article further riled the leadership, Grigsby says, "because of its honesty, and because it was a challenge to the official line." In May of the same year - as a result of pressure from the top, he claims - Grigsby was fired from El Nuevo Diario. He turned to fulltime work at Radio Primerísima, eventually becoming director of the station. Subsequently, he asserts, he was offered reinstatement in the party. "But I'm not interested in returning, because I want to continue being a journalist. I don't want that work to be subject to Party dictates. I'm a Sandinista. But I'm a journalist first and last."

Grigsby moved from being controversial to being downright notorious in the wake of the Sandinista electoral defeat. On his nightly radio show, he presented himself as the voice of the impoverished Sandinista majority. While the masses fought the Chamorro régime's attempts to roll back the Revolution, Grigsby asserted, the Front's leaders - fresh from years of enriching themselves at the public trough - were betraying popular interests by cooperating with the new Chamorro government.

The figure for whom Grigsby reserved his most vituperative criticism was Humberto Ortega, Daniel's brother, who retained his position as Army head by pledging allegiance to the Nicaraguan Constitution and agreeing to implement a large-scale downsizing of the military.

"Humberto Ortega is a man accustomed to power," Grigsby tells me, a tone of derision in his voice. "Since the division of the Front into three 'tendencies' [in the 1970s], he was the man who really led the Tercerista tendency. He had a crucial influence on the ten years of revolution: on decisions taken by the government and the Front.

"He didn't make power into a tool with which to change reality, for the benefit of the great majority. Rather, he used it to consolidate his personal power, and to preserve his privileges. He has certain characteristics - an overbearing nature, arrogance, ambition - which prevent him from being a genuine revolutionary. So after the change of government, he was able very quickly to accommodate himself to the new situation; he used weapons and arms, which were instruments of the revolution, for his interests and his alone.

"What I criticize isn't that he obeys the executive power, nor that he swears allegiance to the Constitution. It's that, from the political point of view, he's taken the role of counsellor, advisor of the new government, to the detriment of the Sandinista Front."

In a series of controversial interviews after Chamorro took power, Ortega called for the Front to change its name, remove leaders over 40 years of age, and adopt a social-democratic ideology which would permit it to join the Socialist International. "This is a man who preferred to stay in power rather than continue as political leader of a revolutionary party," Grigsby argues. "He wants to be a military man. Fine. Let him be one. Let him die there if he wants. But in that case, he should keep his opinions to himself."

As the Army was being cut from 70,000 to 28,000 troops, Grigsby opened his call-in show to disenchanted and disoriented career soldiers, who suddenly found themselves out on the streets with few severance benefits and even sparser job options. Much more provocative, though, was Grigsby's behaviour during the huge strike and near-insurrection in Managua last July. Humberto Ortega vowed his troops would never fire on the strikers. But he pledged his support to President Chamorro, and sent in soldiers to clear barricades set up by Sandinista workers as well as by right-wing militants. Grigsby was furious - vocally so - at the idea of a Sandinista institution adopting a posture of neutrality or even active opposition toward popular agitation and discontent. Ortega, he said, was a traitor to the revolutionary cause.

On September 30, Radio Primerísima's transmitters were bombed, knocking the station off the air. No-one was ever arrested or charged with the crime. At the time, Grigsby openly accused Humberto Ortega of complicity in the attack. Today, he's more cagey. "It could have been anybody. I don't have proof to point to anyone." But his eyes twinkle mischievously.

Was he satisfied with the way the investigation was conducted?

"I can't be satisfied, because there hasn't been any investigation."

Why might that be?

"I imagine because they - the police, the government - are afraid of finding out who did it."

La Primerísima returned to the airwaves by means of a one-kilowatt transmitter that barely covered the central Managua area. Grigsby departed on an overseas tour, appealing to non-governmental organizations and solidarity groups for aid to buy more powerful transmitters. Aid poured in from Nicaraguans, as well as from Spain, Canada, and half a dozen other countries. In April this year, the station returned to full operations. Grigsby is still hunkered down in his regular 10 p.m. time slot; the passion of his polemics is undiminished.

If he's still a Sandinista, where does Grigsby see the Front heading? Where does he think it should be heading?

He shrugs. "I don't know what concrete direction it should take. The July Congress should be an event to purge the ranks, I think: to move ourselves in the direction of a genuine opposition party, rather than a co-governing party. We should elect temporary leaders - a small nucleus - and order them to initiate a national process of consultation in order to elaborate, within two years, a program outlining the statutes and principles of the Front. The most important thing is to recover credibility among the Sandinistas and the people as a whole." That, he thinks, is the agenda the majority wants. But he expects it to be fought every step of the way by highly-placed Sandinistas.

Grigsby's bête noire in this context is Rosario Murillo - former head of the Sandinista Association of Cultural Workers (ASTC), editor of the publication Ventana, and common-law spouse of ex-President (and recently-confirmed Front leader) Daniel Ortega. The feud between Grigsby and Murillo is one of the more famous spats on the Nicaraguan political scene. At the height of his anti-Humberto Ortega campaign in 1990, Murillo flatly accused Grigsby of being a CIA agent.

On Grigsby's office wall, there hangs a cartoon drawn for him by a Primerísima listener. It shows Murillo, tarted up in all her cyberpunk glory, playing chess. Grigsby, facing her across the table, has only one piece left: but it's Justice, the blindfolded woman holding a set of scales. A frustrated Murillo is complaining: "If it weren't for this lady, you'd have been checkmated long ago."

Murillo is renowned for her purist stance vis-à-vis revolutionary ideology and the institutional coherence of the Front. Grigsby sees that as a pose - part of an intricate game-plan designed to bolster the power and influence of a central figure: Daniel Ortega.

To co-opt the reformist energies, Grigsby argues, Murillo is hiding her allegiance to two sacred principles which, in his view, the masses don't share. One is continuity in the leadership of the Front. The other is a defense of what many Nicaraguans call "la piñata," "the grab-bag" - a reference to the children's game of bashing a clay or papier-mâché container to get at the candy and other goodies inside. The political "piñata" was the Sandinistas' transferring of large amounts of state property to individual Nicaraguans during the three-month transition period that followed the electoral defeat. Many top figures are alleged to have feathered their own nests from the giveaways - including Murillo and her common-law husband.

I ask Grigsby how strong he thinks this politically purist, "radical" tendency is among the Front.

"I don't think there's any sector that's purist or radical."

So it's a question of individual personalities, like Rosario Murillo?

"The Front is divided into two sectors, the rich and the poor - just like society as a whole. That's what I'm telling you."

Rosario Murillo leans forward earnestly, propping her elbows on the elegant oak desk.

"Listen. I think you can become an agent even without your knowing it," she says. "By the issues you start addressing, and by addressing them without any consideration of broader context.

"Put it this way. If the United States expected to preserve Somoza's National Guard when the Sandinistas won the war in 1979, then of course they also expected to exterminate the Sandinista Revolution in 1990 - the Sandinista Army, the security forces, and everything else. And if the revolutionaries in Nicaragua proved themselves capable of preserving those institutions, in a fight with the United States - the most powerful enemy in the world! - well, I think you have to be very careful about the way you deal with that.

"Personally, I might not agree with the political positions expressed by Humberto Ortega as head of the Army throughout this last year," Murillo adds. "That's my right, to disagree. But what if, instead of registering my disagreement, I start accusing Humberto Ortega of being a traitor? What am I doing, if I try to pit low-ranking Army officials against high ones, saying that the poor are living in misery while the rich wallow in opulence?

"Don't you have a responsibility, as a revolutionary, to be very careful about what you say, how you criticize what could be mistakes in a given institution - an institution we have managed to preserve for the defense of the people of Nicaragua? You can't act to provoke confrontation within the Army. That's very dangerous! What is your aim - to divide that Army? Do you want Sandinistas fighting against Sandinistas within the Army, from a class perspective?

"Those are the questions I asked William Grigsby. I don't like to say this, but I was the only person who responded to his campaign of defamation. I didn't do it because I live with Daniel Ortega. I did it because I think the same criticisms could be made in a much more constructive, helpful, loving, responsible way.

"I didn't mean to suggest Grigsby received a salary from the CIA. But I did mean to say that you can act as an agent for hostile forces without even knowing it, as a result of your arrogance, your self-righteousness - or, in Grigsby's case, your political ambition, the desire to be acknowledged as a 'voice' and a 'brain'.

"The Nicaraguan people," she says finally, "have suffered too much to let things go down the drain on the basis of individuals' personal resentments."

Murillo takes a breath, and so do I. She has spoken in a hushed voice, but with an almost hypnotic intensity. And it's been tough to get a word in edgeways.

Not that I'd really expected to. "La Rosario's" reputation, after all, precedes her.

On first meeting, the 38-year-old Murillo looks much as you'd imagine from all the stories. She wears a gaily-coloured, '60s-style dress over bright Spandex tights. Her hair is close-cropped, a little punky; she sports huge mismatched earrings, groaning under the weight of their baubles and beads. Her eye shadow is a rather garish tint of blue, and her perfume fills the small room where we're sitting. In conversation, she sometimes lives up to her hippie image, quoting Robert Redford, John Lennon, or Shirley MacLaine more often than Marx or Milan Kundera.

This is the Nicaraguan woman around whom more invective swirls than almost any other you'd care to name. The accusations levelled at Rosario Murillo are sharp indeed: that she is a shameless booster of Daniel, devoting all her energies to advancing his career; that she is an artistic dilettante who took control of the state-sponsored cultural association largely owing to her status as the comandante's companion.

But Murillo is also an accomplished poet in her own right. And she is far from being a parvenu when it comes to revolutionary work. In fact, she was a member of the first "induction" into Sandinista ranks, in the mid- and late-1960s - "Back when you were very few," she says, "when it was like getting into something that was a dream you were sure you wouldn't see realized in your lifetime, but a dream for which you were willing to give your life and go through anything, expecting nothing in return."

There are other things the dragon-lady tales don't tell you. A slightly-built woman, Murillo is soft-spoken, courteous to a fault, with a faint tinge of reticence and shyness. She speaks English nearly perfectly - but carefully, weighing her words. At times she is genuinely eloquent, though when inspiration wanes, her vocabulary tends to float off into the realm of abstract nouns. Like many intellectuals, Murillo seems to use interviews as an opportunity to explore her own thoughts - following her questioner's lead into territory which she, herself, might not have deemed interesting or relevant.

Her responses to the allegations made against her are methodical, rigorous, and extensive. Very extensive. We sit at the oak table for four hours solid, during which time I rarely open my mouth, except to insert a sandwich she orders for me.

She joined the Sandinista Front in 1969, she tells me. During the 1970s, she worked at the opposition paper La Prensa as a secretary to the late editor Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, Violeta's husband. Under the Sandinista government, in addition to serving as director of the ASTC, she edited Ventana, the cultural supplement to the daily Barricada. Much of the criticism raised against Murillo in the last year and a half concerns the way in which Ventana increasingly has become her personal mouthpiece. Murillo concedes her recent editorial dominance, but ascribes it to staff shortages rather than any megalomania on her part.

In the early summer of 1990, in Ventana and in an opinion piece written for El Nuevo Diario, Murillo launched a polemic against nearly every other organ of the Sandinista or pro-Sandinista press - including Barricada, the official party daily at that time, in which her Ventana still appeared as a weekly supplement. According to Murillo, a "sect" had commandeered the Sandinista media outlets "for purposes of personal projection, both at the level of ideas and currents and at the level of appointing themselves alternative figures of the Revolution."

Her main targets, in addition to Barricada, were Gente, the popular Barricada supplement edited by feminist activist Sofía Montenegro, and La Semana Cómica, run by Róger Sánchez, a brilliant satirist and cartoonist who died of cancer in late 1990. All three publications, Murillo charged, were being used "to attack and discredit the Sandinista Front," "to promote hatred of women toward men [apparently a reference to Sofía Montenegro's feminist stance], anti-party feeling, [and] disrespect for the Revolution's symbols."

The vitriolic broadside flabbergasted many Sandinistas. Murillo says today that "I don't think everything I've said or during the last year has been correct, appropriate, or respectful. I think I've made mistakes." But she still maintains the media outlets she attacked were guilty of launching an insincere, excessive, and unsubstantiated campaign of criticism against the Front's leadership, and especially against Sandinista government policies in the immediate aftermath of the election defeat.

What criticisms does she reject? Well, those regarding the "piñata," for one. "The famous piñata! Well, I defend it. And I will defend it to the end of my days. Why? Because I'm a witness to that piñata. I know what it meant.

"I'm not talking here about people who might have turned a profit from it, or people who might have ended up with two or three houses. That could have happened. If it did, you should denounce it, and we have an ethical commission to deal with it. But aside from that, you have tens of thousands of people who were given the right to own the house they lived in, or the car they drove themselves around in, or the right to a piece of land to work when they were left without jobs.

"Those people came to you, pleading. They came to this building, to this door." She points out the window of the Casa Fernando Gordillo, the cultural centre where Ventana is based. "Mothers of martyrs; relatives of people that had given their lives for this Revolution. They were asking for a freezer or refrigerator, so they could sell ice or gaseosas [soft-drinks] from their houses, and earn some kind of living that way. We had buses here to take them to Government House, where they were given something to help them provide for themselves. That's the 'piñata'. Well, why not defend it?"

There is, though, the matter of her own residence - a mansion, seized from a pro-Somoza businessman, that now serves the Nicaraguan right-wing as a symbol of piñata excess. Before the Chamorro government took power, Rosario and Daniel received a deed to their property for the token payment of $3000. In the face of intense pressure and government eviction threats, they have refused to budge.

"My father owned lots of properties that I could have inherited," Murillo says staunchly. "I gave it all up for the Revolution. I used to be a rich person. I have nothing now - only the house where we live, which doesn't belong to me personally. I live on what I earn from my work.

"Many, many Sandinistas did that. We gave up everything, because we were raised on the ideal that the Revolution would take care of everything - even of our children if we died. Everything was in the government's name. So of course we were concerned about would happen to our houses after a change of government.

"When the criticism started from the right wing, even before the actual transfer of power, people were able to see it was only one more rightist campaign to undermine the revolutionary movement," Murillo contends. "I mean, we've been through thousands of such campaigns. But when our own compañeros began accusing us - Sandinistas calling other Sandinistas 'ladrones', robbers - I couldn't believe it!"

Murillo says she found the criticisms profoundly disillusioning. "I thought that losing the elections meant the Sandinistas would get back together, be as united as ever. An underground brotherhood, like we'd been before July 1979. I had a romantic perspective. What did I see instead? People ripping off the skin of their own brothers and sisters, and in our own media!

"Individuals make mistake. But to call into question the whole conduct of the Sandinista leadership? I think that's unfair. Unfair in terms of the Sandinista movement, of the Nicaraguan people that believe in the Sandinista movement and see it as their hope for a dignified future. If you undermine the moral strength of that movement, you're destroying an instrument of hope of the vast majority of your people."

We are speaking before the Sandinista Congress, for which Murillo has limited hopes or expectations. "I know it has to take place, I know it's important, but I also know it isn't anything that's going to make a dramatic change to the Frente Sandinista. Why? Because it's almost impossible for anyone, anywhere in the world, to define a strategy that looks five years down the road. It's absurd. The world is changing every day!"

Her greatest desire, she says, is for the Congress to renew a sense of unity among Sandinista ranks. "In terms of the Sandinista Front, if we're to be coherent in our principles, then personally, I'd like to see a lot of people kicked out. I'm not going to say any names. But then I also think: Well, is this the right time to be thinking about throwing people out? If our strategy is to defend what we've achieved over these years, and if all Sandinistas can agree upon a reaffirmation of the founding ideals we embraced - justice and solidarity and human growth - then what good does it do to sow division?"

She thinks imbuing the Front's basic principles with new life should take precedence over a specific electoral strategy to reclaim power in 1996. "We should ensure the values and principles, and defend the accomplishments, even if it means that for some people, the Sandinista Party doesn't represent an option for government. If representing the interests of the majority of Nicaraguans should mean continuing this struggle against the United States, and even losing another election to the United States, I prefer to represent the majority.

"We were never conceived of as an electoral party. And to me it's absolutely wise not to turn the Front into a rigid party. We should remain a Front, which would mean that within the movement there would be people from different social and economic levels, different background. This is consistent with the historic reality of the Sandinista Front, the revolutionary movement, and Nicaraguan society as well.

"We can't change the basics," Murillo sighs.

"This is what people have fought and died for. And it's what people are

fighting for now - with no one telling or forcing them to."

But in the course of fifteen hours of interviews, it's inevitable the family element will work its way in. After all, plenty of Nicaraguans visited their mothers the day after the Sandinistas' shocking election defeat in February 1990. But Carlos Fernando's visit was made (in the company of defeated President Daniel Ortega) to congratulate his mother - "Doña Violeta" Chamorro, a staunch anti-Sandinista - on her presidential election victory. ("There was no chance to have a private conversation with her. I just told her she would be shouldering a big responsibility from now on, and I expected her to be able to handle it. Something like that.")

Then there's the matter of his father. Over drinks at his house one night, Carlos Fernando tells me of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro's influence on him. "I guess it was more personal, centred on certain basic values: being transparent, being faithful to your own beliefs, having some degree of tolerance, being responsible for your own actions. And there was also his strongly anti-Somocista attitude, of course."

Indeed. Pedro Joaquín Chamorro was publisher of the daily La Prensa, and the best-known opposition figure in Nicaragua during the years of the Somoza dictatorship. He was assassinated, allegedly by Somoza's henchmen, in January 1978. The killing sparked massive protests which contributed to Somoza's overthrow just over a year later.

And so it goes. "My uncle" - that's Xavier Chamorro, Pedro Joaquín's brother. Xavier publishes El Nuevo Diario, Nicaragua's third daily paper, born from a core majority of La Prensa staff who jumped ship in 1980 to protest the paper's increasingly anti-Sandinista line. Until her election victory, Doña Violeta owned a controlling interest in La Prensa. Violeta's daughter Cristiana, Carlos Fernando's sister, still sits on the La Prensa Board of Directors. Pedro Joaquín Jr., Carlos Fernando's brother, took time off from La Prensa to accept a posting as Nicaraguan Ambassador to Taiwan - an important and strategic assignment, since Taiwanese investment (particularly in exploitation of Nicaragua's rainforest) is being eagerly sought by the new Chamorro government. Another of Carlos Fernando's sisters was a Sandinista diplomat during the revolutionary years.

It's amusing to imagine this collection of strong Sandinista supporters and stridently anti-Sandinista opponents sharing a dinner table. Actually, there's no need to imagine it: during the 1980s the Chamorros met weekly for family suppers, a tradition which continues today. Politics as a subject of discussion was, and is, taboo.

With luck, there's some symbolism in all this. At least, the picture of the Chamorro clan appears to offer some hope for the future, as Nicaragua stumbles forward under the weight of economic crisis and continuing political polarization.

The Chamorros are only the best-known of the thousands of families who found the Revolution running like a fault-line through kith and kin. Many relatives - usually from poorer families - ended up facing each other on the battlefield. Those that sought to preserve a measure of normal family life through the upheavals of the 1980s learned a lot about the art of compromise. Today, with "depolarization" all the rage in Nicaraguan politics, that most intimate experience - coexistence with political opponents who are also beloved relatives - may prove indispensable.

On January 30 of this year, Carlos Fernando Chamorro's paper Barricada - the "official organ of the Sandinista Front" from the first days of the revolutionary era - unveiled a new and in some ways radically revamped version of itself. Gone was the insurrectionary logo alongside the masthead: a guerrilla crouched behind a barricade of paving stones, taking aim with a rifle. Most striking of all was the change in the paper's slogan, which now reads, "In the National Interest."

In an editorial some five months after the electoral defeat, Chamorro wrote that Barricada aimed to become "a broad forum of popular and national debate ... with no restrictions other than the demand that contributors display a constructive and unifying spirit."

This remarkable evolution in Barricada's role and function is what I went to Nicaragua to study. And if you study Barricada, you are studying, to a greater or lesser degree, Carlos Fernando Chamorro. Chamorro joined the paper only a few weeks after it was born, in July 1979. He was 23. Shortly afterward, he became the paper's director, a position he has held ever since.

He has a reputation as a rather austere character, and his first greeting to me is restrained and correct. Over hours of interviews, though, Chamorro unwinds a lot. He's as reflective, thoughtful, and articulate as you would expect one of Nicaragua's most prominent intellectuals to be. But there's a certain playful insouciance to him as well. He swears there's no significance to the Charlie Chaplin photo he keeps in his office, but I wonder.

Chamorro tells me that over 11 years of Sandinista rule, Barricada became a "para-statal" organ. The interpenetration of party and revolutionary state was so intimate that the two were usually indistinguishable.

"If you like, the party considered the state as the most important instrument of its revolutionary policy," he says. "When you lose the elections, that's finished! The state is no longer the axis of cohesion. The professional apparatus of the party disappears from one day to the other, because you don't have the financial resources to sustain it."

The impact on the Sandinistas' official organ was equally immediate and far-reaching. "Barricada goes its own way," Chamorro tells me. "It's not a matter of the party having more or less control over it. It's a recognition of a new and different reality. It makes it easier for everybody to understand that you now need a very strong newspaper, one that will be accepted by the population as a whole and not only by the Sandinistas."

In fact, the election defeat allowed Chamorro to accelerate plans for change at Barricada which had been in the works since 1987, when the long-running war against U.S.-supported Contras began to wind down. After years of civil strife and extreme political polarization, the newspaper - and party leaders - saw a need to open Barricada to a broader diversity of viewpoints. The paper would work to decrease the mutual antipathies, fuelled by angry rhetoric, which were held to be poisoning social and political discourse in Nicaragua.

In the period immediately following the 1990 elections, the project of depolarization became more urgent, and the changes correspondingly more sweeping. Thousands of Contra troops were demobilizing and reintegrating, not always smoothly, into the social fabric. Thousands of anti-Sandinista Nicaraguans were returning from self-imposed exile in the United States. And the country's crushing economic problems only worsened, forcing all sectors to seek a modus vivendi that would allow the country to rebuild.

Chamorro himself set the tone for the new Barricada by commissioning a controversial interview with Managua Mayor Arnoldo Alemán, an arch rightwinger who has waged a one-man campaign against the material legacy of Sandinista rule.

"I edited the interview myself, and I defend that decision totally," Chamorro says. "Whether he's a fascist or not, Arnoldo Alemán is the Mayor of Managua. We consciously wanted to send a signal that anybody who gave an interview to Barricada would have his or her ideas respected. Alemán was the best signal."

Barricada's general stance toward the Chamorro government follows the broad outlines of Sandinista opposition strategy, which is based in turn on the concertación agreements between the Sandinistas and Violeta Chamorro's team in the transition period following the elections. The Sandinistas have sought to keep a critical distance from Chamorro government policies. But in return for continued control over the army and security forces (something no popular movement in Central America would casually surrender), they have supported the Chamorro regime's applications for foreign aid, helped in negotiations between the government and pro-Sandinista unions, and made it clear they will seek a return to power by peaceful, electoral means only.

"It would be wrong, totally wrong, for us to deny the legitimacy of this government," Chamorro argues. "If we decide they don't exist, that they're a fraud, that they are simply the sons of Yanqui imperialism ... well, what we have to do is organize a coup d'état or a military insurrection. But they exist. And we have to dispute their ideas against our ideas."

There is, in all this, a sense of relief that Barricada's writers and editors can write more or less what they want, now that the paper is freed of the need to disseminate the Sandinista party line and nothing else. Chamorro, and everyone else I spoke with at the paper, readily concedes that during the Sandinista years in power, Barricada was constrained to the point of suffocation by its official, para-statal function.

Nonetheless, Barricada managed to preserve something of the journalist's traditional approach and value-system. "Our criteria as journalists was that you had to take political considerations into account," says Chamorro. "But you couldn't subordinate the journalistic importance [of a story], or the public interest, to political considerations all the time. There was always a fight to have our own agenda."

A crucial consideration in Barricada's new, post-election orientation is the financial straits in which the paper finds itself. When the Chamorro government took power, it cancelled Barricada's contract with the Ministry of Education to print state textbooks. Another crucial source of funding, state-sector advertising, all but disappeared.

The broader economic crisis has had a powerful impact on all three of Managua's daily papers. With most Nicaraguans struggling to put a bare quantity of rice and beans on the table, potential readership for any publication is strictly limited: a single copy of Barricada can cost 20 percent of a worker's daily salary.

The paper has developed a variety of free-market strategies to secure more readers and advertising revenue. To compete with the freewheeling, sensationalistic leftwing daily El Nuevo Diario, Barricada is bolstering its entertainment coverage. It's also dabbling in a bit of periodismo amarillo - "yellow journalism," though less splashy than that of Nuevo Diario. There are more stories on crime, more women in bathing suits, more gossip about Madonna's lesbian love-life.

Barricada is also seeking outside clients for its printing facilities, by far the most sophisticated in Nicaragua. This has made for some strange marriages of convenience. El Nicaragüense, the organ of the rightwing businessman's organization COSEP, is printed at the Barricada plant. It seems El Nicaragüense's editors have more intransigent political disputes with the publishers of La Prensa across town - whom they accuse of taking an overly "conciliatory" line toward the Sandinistas!

"The most I can see now is a newspaper which will have much more the characteristics of an institution," he answers. "More autonomous. I'm not saying less Sandinista, but with its own internal rules that are more strongly defined and institutionalized. And I expect our readers themselves to have much more of an influence on what you find in the paper."

What about Barricada's relationship with the party that gave birth to it?

"I hope by then there'll be an understanding among the Sandinista leadership that Barricada has to be seen as a newspaper of the Sandinista movement in general. Whatever happens with the Sandinistas, I think the best thing for the movement will be to have a strong newspaper that can be seen by the population as a whole, and the Sandinistas in particular, as a real leader of public opinion."

It could be Sofía's credo.

Montenegro, 37, is no stranger to complications, nor to controversy. She has worked at Barricada from the very beginning, when the paper was put together by a hodgepodge amalgam of untrained militants, radio journalists, and staff on loan from La Prensa (whose offices had been bombed out in the final stages of the 1979 insurrection). She edited Barricada's editorial page for much of the 1980s. Today she runs Gente, the newspaper's most popular and lively weekly supplement. It's full of daring commentary on sexuality, gender issues, and other subjects traditionally paid little attention in the Nicaraguan media.

During the '80s, though, Montenegro was sanctioned several times by the Sandinista Front and expelled twice for breaches of discipline. When not in hot water with the party leadership, Sofía was off in the northern mountains fighting Contras ("I don't know if I killed anyone; it was enough I didn't kill myself!"), or travelling the world as a Sandinista representative. She also positioned herself at the forefront of the unofficial Nicaraguan women's movement: together with Nicaraguan writer Gioconda Belli, Sofía was a founder of the Party of the Erotic Left.

The what?

"That name came about as a reflection of our thinking in certain areas," Sofía remembers. "We felt the revolution shouldn't only be addressing itself to issues of economics and production, but all parts of society and people's subjectivity. That meant transforming the reproductive side of society, where women are stuck. It also meant an emotional transformation of the population: raising the banner of love.

"Obviously, this moved us into the area of sexuality, along with all the other subjective aspects of the human experience. We felt the prevailing economic and social model was built on the repression of sexuality, and on a mode of sexuality which kept women on the bottom of the pile. We sought to reintegrate pleasure and individual self-nourishment, promoting the individuality of each citizen in a society which, because of tradition and political culture, had always placed the community and collective welfare above the individual.

"It was clear, then, that we were an erotic left. Not a sensual left, but an erotic one."

The Sandinista election defeat has brought conflict between two broad strands of the Nicaraguan women's movement into the open. The "official" strand, centred around the Association of Nicaraguan Women (AMNLAE), shared the fate of many Sandinista mass organizations over the revolutionary decade. It became a relatively hierarchical body, integrated into the revolutionary state, directing its principal energies toward support for the war effort and Sandinista national campaigns. Meanwhile, a smaller, looser-knit movement arose in the mid-1980s. The Party of the Erotic Left was one outgrowth of it, a think-tank which emerged among women intellectuals in Managua.

The organizing efforts of this strand of the movement centred around issues like reproductive choice, women's health, wage parity, and daycare centres. According to Sofía, the momentum of this kind of agitation grew as the war against the Contras took young men away to the front. Women, especially younger ones, took charge of economic production.

Montenegro says that these women "quickly became much more belligerent and assertive in their demands, especially around economic issues like salaries. They began to enter a stage of awareness which marked the beginning of a consciousness for themselves. That assertiveness and self-assurance was born of the realization that they could handle things on their own. I think that was the beginning of a genuinely feminist consciousness in Nicaragua, and that's the field we're now trying to sow."

AMNLAE, and the Sandinista Front in general, "failed to recognize and adjust to the new reality," Sofía believes. And at that point - perhaps from 1987 onward - "AMNLAE began to lose its national representativeness. The FSLN knew this was happening, but it constantly put off adapting to the situation. The Front would always tell us [critics]: 'You're too far ahead of the masses, the majority of women are not ready for this new agenda. You're a bunch of petty-bourgeois intellectuals who are far too radical on the women's issue.'

"Well, I think history's proving us right."

Since August 1990, the coalition has been holding seminars for women from different regions of the country, trying to come up with a consensus on strategy. "At one of those seminars," Sofía recalls, "a peasant woman stood up and said something very beautiful. 'So far,' she said, 'we've been the humble wife of the Sandinista Front. Now it's time to make the Front our lover.'

"In other words, we're going to have a divorce, but on good terms, and we'll take back the old husband as a lover instead. A husband gives orders. He's the master of the house. But a lover isn't. He may come or he may go; you're essentially on your own. By taking this line, you're doing away with the patronizing and the paternalism that has characterized relations between the Front and the women's movement up until now."

We talk perhaps a dozen times, some 25 hours in all, cramped into her corner office at Gente. Montenegro smokes like a chimney throughout, and "talks like a truck-driver" (as she cheerfully puts it).

There is a gentle and uncertain side to her as well. She speaks with painful openness of her complex and traumatic relationship with her mother. For years, Sofía, as a committed Sandinista, took family blame for the death of her brother, Franklin. (A Somocista National Guardsman, Franklin Montenegro was killed in late 1979, allegedly while trying to escape from a Sandinista prison.) It comes as no surprise to me that Sofía and Carlos Fernando Chamorro seem almost brother and sister. Both know how deep family divisions can run.

Add to these filial stresses Sofía's stormy relationship with the Sandinista leadership; factor in a life-threatening illness contracted during her stint in the mountains; and you have the recipe for mental and physical breakdown, which Sofía courted at a couple of points in the mid-1980s. She speaks today with the sagacity of the survivor. It gives her, she says, "a certain advantage" in coming to terms with the new reality in Nicaragua.

"The Sandinista Front is going through its own small death. I'm lucky, because I feel I've died before. Some people are for the first time having to confront death and rebirth, and a lot of them are dropping to the floor under the burden. They've lost, some of them, their reason for living."

A few months after the defeat, Montenegro put together a special issue of Gente on the topic of mourning. "We're not experiencing someone's death as such, not even the death of the party. Nonetheless, it's an enormous sense of loss which, psychologically, has the same effects as mourning for someone dear to you."