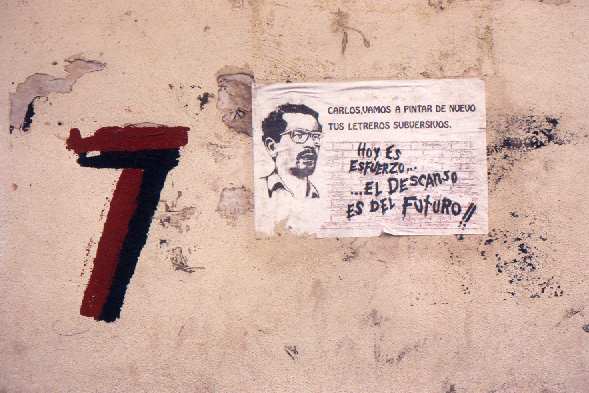

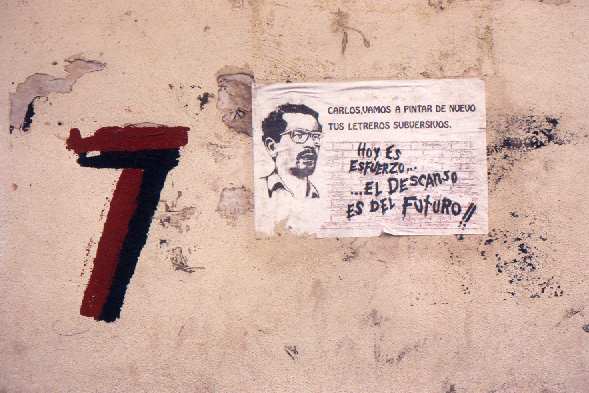

Graffiti in Nicaragua, 1986, commemorating the seventh anniversary of the revolution and the death of Carlos Fonseca ten years earlier: "Carlos: We will paint anew your subversive signs: Today is for struggle - Rest is for the future." Photo by Adam Jones.

Managua, Nicaragua. The Aeronica jet banks low over Sandino International Airport and the city sprawls out below us, hugging the shores of the lake. Away in the distance is the mountainside with its huge "FSLN" insignia. We skim past a ditch full of the carcasses of World War II-era Corvair fighters, past a couple of hangars housing dangerous-looking MI-24 attack helicopters. Then we're down.

This is where abstractions become reality. In Canada, Nicaragua means war, peace, independence, anti-imperialism, self-determination - pick your ideal. Here it is a humid dusk, a rickety ride down streets whose paving stones were torn up for barricades during the insurrection. Billboards. Dust and diesel. A young Sandinista couple in khaki military garb, strolling along a sidestreet, locked in an embrace.

I went expecting a defensive, cowed revolution, a social transformation stuck in a holding pattern. I came away marvelling at the energy and vitality of the Nicaraguans I met: their generosity and confidence and resilience. In a very real way it seems, as Anna-Patricia Elvir told we Tools for Peace delegates at our wrap-up meeting, that "the Revolution is more vibrant, more alive than ever."

Anna-Patricia is a slight, relaxed 25-year-old with a wry smile and omnipresent cigarette. She is also General Secretary of the CNSP, the organization responsible for helping to shape the political dimension of solidarity campaigns like Tools for Peace. On our first morning in Managua, at CNSP headquarters in the city's Bologna district, she leans back in her chair and tells us where her country stands.

"Right now there's nothing new happening in Nicaragua. The present conditions are the product of six years of U.S. aggression. But the attack has increased. In 1982, we were still talking about development; we had 36 major investment plans and hundreds of smaller ones." The wry smile. "Then reality intruded. For investment you need stability and the kind of material and technological base that Nicaragua just doesn't have. As of last year we began to talk about simple survival."

For Tools for Peace, it means a move away from the kind of broad, somewhat chaotic collection campaigns of years past, and a shift in the direction of a more focused, more overtly political campaign that concentrates on the collection en masse of a few priority items. Hammers. Saws. Rubber boots. Pencils. Blankets. Sanitary napkins. At Berta Calderón Women's Hospital in Managua, most of the bedsheets have been destroyed by patients' tearing them up for rags during their periods. The nation's supply of sanitary napkins is miniscule, and is not expected to last beyond October.

Anna-Patricia is the first of dozens of Nicaraguans to tell us that Tools for Peace, and the international solidarity it symbolizes, are of immense importance. There are ways of saying this sort of thing in a pat, token kind of way - Thanks a lot, comrades - and then there are ways of saying it that can make you glow or bring tears to your eyes, make you realize that people are actually counting on you.

In Nicaragua we get the latter, day after day, from people who speak to us as friends: people who in many cases are our own age, like Anna-Patricia - thrust into positions of responsibility that in North America would be reserved for safe middle-aged bureaucrats. "The people of Nicaragua see you foreigners as the hope," Anna-Patricia says. "When Daniel Ortega goes to Paris, or New York, or Harare, and we see on TV thousands of people cheering him, it fills us with pride. And we see that even if we die, there are others around the world to carry on the battle."

Tools for Peace, she tells us, "means a machete for a Nicaraguan peasant being attacked by U.S. terrorism. It means a roof over his head, notebooks for his children who are continuing their education in spite of the war. It means medicine for our people to maintain the advances made in health since 1979." This year, as last, some of the material aid received in Nicaragua (particularly the industrial and agricultural implements) will be sold, rather than given outright, to workers and peasants in the country.

"We feel people should receive foreign aid, but also should give something of themselves in return, to imbue Nicaraguans with the kind of self-sufficiency which is going to be vital in the future. Originally we had a very paternalistic attitude to the workers, you know. It encouraged passivity on their part, because work for them had always been a form of exploitation." The money collected from the sales is ploughed back into the impoverished economy.

Conceptually, it's a little difficult to get used to. Then you realize that this is how maximum value is obtained. Nicaragua, after five years of brutal war, with over half the national budget going to the military defence of the country and the revolution, is in an emergency situation.

And if it's a problem for us, what is it like for the Nicaraguans like Anna-Patricia who have to handle the distribution of aid? "Our country is so impoverished," she says matter-of-factly, "that every time a product arrives, twenty hands stretch out to grab it. We have to decide who should have it and when. We've learned over the years when we are faced with three hungry faces to say no to two of them. We've had to make difficult decisions and sometimes cruel ones, with the coldest analytical reasoning."

She is nothing if not straightforward.

He's happy to oblige. After the triumph, he says, La Terraza owed a great deal of money to its personnel. The owners sold off most of the fixtures, down to the furniture, to pay off some of the debt. The place still wasn't viable. So the employees took it over, and were apportioned shares in the enterprise according to the debt they were owed.

Today, even with the economy in shambles, La Terraza is making money; lesser shareholders take the same percentage of profits as larger ones. Felix points out that now the restaurant is open to anyone at all, not just the elite - but prices are high by Managua standards, and most of the clientele seems pretty well-heeled.

What about the personal changes in his life since 1979? Felix grins. "You know, I always wanted to set up a restaurant of my own, and after the revolution we had one handed to us!"

After lunch we lounge around at Xilaó, an idyllic volcanic lake in the hills around Managua. Opportunities for indolence will be few and far between on this trip, and we are encouraged to make the most of them. The sky is bright blue, the water warm. The concrete pathways scorch our soles. Two young local kids, Rodolfo and Manuel, hitch a ride back to the city with us. They receive a lot of attention and some camera clicking.

We promise to send them a couple of copies of the photos. Where do they live in Managua? But addresses in the capital city are notoriously vague, sometimes centring on where a particular building once stood, years ago. They don't seem to have much of a conception of "address": they know where they live, so what's the problem? We try again. Perhaps their parents work at a more coherent location.

"What does your father do?" Scott, our translator, asks Manuel.

"He does nothing," Manuel replies. "They killed him in the war."

"How does your family get by?"

"My mother sells white wrapping paper in the market."

There is a pause. "Rodolfo?"

Rodolfo says his father is in prison. He was a member of Somoza's National Guard, and he committed some crimes.

We let the two off in town, Rodolfo fiddling with a bright new Canada pin impaled on his grimy T-shirt. I feel sad and speechless until I notice the twinkle in Scott's eye. He's smiling, amused. "If we picked them up tomorrow, they'd probably tell us something completely different."

Scott learned his Spanish in Spain, and speaks it like a native. He has lived in Nicaragua for three years and is married to a Salvadorean woman. In 1980, he flew into El Salvador with Quebec MP Jacques Couture to attend the funeral of six FDR opposition members assassinated by Salvadorean security forces. As they were passing through the airport to their waiting van, they met two American nuns, Maryknoll sisters, awaiting the arrival of two other sisters from Nicaragua. Scott thinks he and his party might have been the last to speak to the Maryknolls, who left the airport about half an hour later and were seized by soldiers, raped, and brutally murdered on their way back to the capital.

Alma is 23: cheerful and animated, with a reckless, insouciant intelligence. After dinner and some idle conversation, we ask to hear her story.

The first thing she tells us is she feels proud and privileged to be part of the revolution. She grew up in León and got involved with the active anti-Somoza movement there which produced people like Omar Cabezas, author of the classic Fire from the Mountain. Eventually her family moved to Managua.

"In 1978 I joined the FSLN squad in my barrio. It had various functions: mainly political work, plus some small-scale military work. We started to make contact bombs, very rudimentary: newspaper, stones, powder, masking tape; that was that. And we went out painting the walls in the wee hours of the morning.

"I want to say something, and I don't know if you'll understand its importance: the family thing. I mean, my family didn't know I'd joined the FSLN, and suddenly I was having all these male visitors, compañeros in the struggle, older than me, and I was going out at all hours of the night. My mother was saying, 'What's going on here?' So eventually she started coming out with me! And she found out what I was up to. She said, 'Okay, fine, go and do what you want.' That was very important to me.

"In 1979, I moved on to another kind of work. At that time, each FSLN squad - tactical combat units, they were called - was responsible for several neighbourhoods in Managua. In April 1979, these units with their popular action committees were planning on taking over a neighbourhood - the one where we were living. Our task was to distract the National Guard with diversionary tactics. One of these tactics was making the contact bombs, which you'd throw late in the evening or really early in the morning when the Guard was patrolling, to scare them shitless.

"One of the bombs exploded in my hands."

She pauses and knits her brows in concentration.

"Everything we were doing was illegal. You have to realize that: it's what we lived with; we were mentally prepared for disaster. It didn't matter. Just to be young at that time was a crime in itself. When the bomb went off, I think I lost consciousness for a few seconds. There were a few of us in there, we were lucky; I was the only one seriously hurt. The first thing we thought about was how to get the hell out of there, the garage where we were putting these devices together. I couldn't go out in the condition I was in."

She waited there with her hands blown off. "I remember telling myself of everything the struggle meant to us, to keep me going. Who could get to us first, the Guard or the compañeros? Well, it was a compañero. They took me to a clinic, a maternity clinic! We had to lie to the doctors, and of course, they didn't believe us. It was a tense situation and they shifted me after three days to a safe house, gave me what care they could. They operated on me with razor blades."

When the insurrection came, her comrades told her she would have to go to an embassy and ask for asylum; keeping her hidden was becoming too risky. "I found that option very hard to take. But it was an order." She went to the Venezuelan embassy, but at the end of June her compañeros came and took her with them on the FSLN's own "Long March," the tactical retreat from Managua to Masaya that immediately preceded the final victory. "Two days before the Triumph they took me to Costa Rica. That's there I was on July 19, 1979. Then they took me to Cuba for medical treatment. I was there till December and came back to join the literacy brigades."

Doctors in East Germany outfitted her with the prosthetic "claws" that she uses to eat and write and rummage for cigarettes. When she returned to Nicaragua she joined the Sandinista Youth League, in which she is now an official.

We chat on into the evening, the excellent Flor de Caña rum disappearing at an even pace. Alma talks a little about subjects like the general amnesty for ex-National Guardsmen and the contra war. I've heard from Anna-Patricia about her boyfriend, and I ask the question, delicately. She shrugs. "I had a boyfriend. He was killed last year. It's not an easy thing to talk about." For the first time, there are tears in her eyes.

It has been a harsh year climatically for Nicaragua. Thirty-five million dollars was lost in this year's cotton harvest alone due to drought conditions. We have to remind ourselves, wiping the sweat from our brows or applying protective grease to chapped lips, that this is supposed to be the height of the rainy season. But the land, viewed from the window of our León-bound minibus, is lovely nonetheless. For even the scruffiest vista there is a backdrop of brilliant hills, covered with billowing clouds of green foliage.

After the aimless, earthquake-shattered sprawl of Managua, León is a spectacular city. It is all crumbling colonial grandeur, fiery murals, rich slashes of Sandinista red-and-black nestled among bullet holes on every plaster façade. Founded in 1610, it is Nicaragua's second-largest city, and perhaps its most staunchly militant. Carlos Fonseca, the pre-eminent founder of the Sandinista movement, came from here; León is known as "The City of the Three Insurrections" for the uprisings against Somoza mounted in 1959, 1978, and - victoriously - 1979. I find it impossible to walk the streets without my pace quickening to a march and my heart beating faster.

On Sunday morning in León, a couple of hundred raucous kids gather in the central plaza for a rally of the Association of Sandinista Children (ANS). The cathedral bells peal. In response, the plaza's tinny loudspeakers blare a familiar melody, which takes me a minute to pick up on. It is John Cougar Mellencamp, "R.O.C.K. in the U.S.A." I sing along, laughing at the incongruity of it all.

A couple of blocks away a ragtag group of children drags a dog around on a rope leash, whacking and slashing at it with sticks and leather belts, laughing gleefully as it yelps and dodges. They deal it a few sharp strokes for good measure as it lies prostrate on the ground. "The dog is loco," they tell me warily. But it doesn't look crazy, just exhausted and dazed; it pants, eyes glazed over, and lets me stroke its paw soothingly. I want to tell the children that just down the road is the building where the National Guard once took prisoners for torture, and giggled with the same gratuitous infliction of pain on fellow creatures. But I don't speak Spanish.

Gladys Baéz is one of the most famous women in Nicaragua: a true hero to thousands for her work in the revolution (she was a close comrade-in-arms of Carlos Fonseca); a member of the National Assembly and the Sandinista Assembly. Smiling, with long twin braids halfway down her back, she sits with us in a stiflingly close meeting room in León and talks about the country's predicament.

"What we see coming is a tremendous period of hunger. All the mass organizations are encouraging people to plant family and community gardens. Meanwhile, we can only hope for better results from the second crop in 1986."

And again we hear it: "There are two things that really strengthen our hope for the future. One is the immense effort made by our own people; the other is the efforts of international solidarity workers like you. We know your expectations of us. We won't let you down."

We talk for a while about agriculture and the impact of Tools for Peace in this region, which has been very positive. On the way out, I spy a slogan scrawled in the lobby. Nuestro mejor triunfo es cumplir siete años: Our greatest victory is to have made it through seven years.

Francisco, a man of movie-star good looks, is Assistant Manager of fishery plant operations at Corinto. Graciously, in a soft voice, he delivers a numbing account of the calamities that have struck the fishing industry at Corinto.

Twenty-two shrimp fishing vessels currently operate out of the port. Most of them are 16 to 18 years old and in need of constant repair. In May 1983, Corinto's oil tanks were attacked for the first time, by air, stopping work at the port for five days. In December of the same year, two months after the devastation at the refinery, a speedboat attack blew up a fishing boat, killing the captain.

In 1984 the port was mined by the CIA's "unilaterally controlled Latino assets." When foreign vessels struck the mines, Francisco says, "Foreign captains began to insist that Nicaraguan boats precede them into port - guinea pigs, to make sure the path was clear." Five boats were sunk. They were refloated, but some still have not been repaired.

A loan from the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), granted under the Carter Administration for offices and ship-repair docks, did not filter through until 1984. A significant portion of it was blocked by the Reagan Administration. About 60 percent of the loan, or US $24 million, still has not been delivered. "We're afraid it too will be blocked by the U.S.," Francisco says. In the meantime, of course, prices - for construction and materials, as for everything else - have risen significantly.

"In order to keep going here we've had to ask our workers to make an immense effort. They've had very little theoretical training; everything's been learned on the job. Our potential production capacity is 250,000 pounds of shrimp a month. But the deficiencies in our infrastructure mean we could only feasibly produce 100,000 pounds, and right now a lot less."

Nature, too, has not been kind this year. The drought that kills the cotton crop inland also warms the waters close to shore. The shrimp head for cooler climes further out, and that makes them harder to catch. Francisco estimates that the plant is working at only 20 percent capacity overall. "At the moment seafood exports account for about 4 percent of the country's exports. If we were producing at capacity, it would be closer to 25 percent."

Afterward, painfully, we tour the dock area. Several of the boats that hit mines are visible in drydock, the wooden-hulled ones showing large patches of fresh planking where they were ripped open. Further down wallow a few derelict vessels, half submerged. From the end of one of the piers, we can see the tangled ruins of the refinery tank destroyed in the contra attack. Another, also set ablaze, has a scorched and lopsided appearance. I make myself look at the scene for a long time, trying to etch it indelibly into my mind. This is the reality.

She discusses the risks in a no-nonsense way. "It's no game. We're not out to get ourselves martyred. You take what security measures you can. I mean, I don't want to die; I have daughters. You carry your gun so if you're attacked, you can at least get off a couple of shots. That's not going to be much help if you run over a land mine, of course. ...

"It's a matter of luck. Any number of times we've been told a road is safe, driven along it, and found out later that five or ten minutes after we passed a certain point, the contras passed by too."

Region VI comprises the provinces of Matagalpa and Jinotega. Together with Region I, to the west, it is where most of the war is being fought. Contra operations have forced thousands of peasants from their homes and land. They have been relocated in asentamientos, resettlement camps, mostly organized into agricultural cooperatives. Coping with the flood of displaced campesinos with the limited resources available has proved an immense and complex task.

In priority areas like Region VI, an aid project like Tools for Peace can accomplish a great deal. "In 1984, we were deluged with materials from the campaign," says Karla's friend, Marianne, who works directly with the asentamientos. "We worked day and night on the inventory and more than 3000 families here ended up benefitting directly, mainly with clothes and tools to build their own houses."

The regional authorities are trying to ensure that each resettlement camp has at least a school, visits from nurses who move among the settlements giving medical attention, and potable water systems. (Most of the water in rural areas is contaminated by the rotted husks of coffee beans, and by animal excrement.) So far some $20 million has been spent on the relocation programs. This year the budget has been cut - another casualty of spiralling defense costs - and Marianne and her co-workers are depending on funds from foreign solidarity groups.

"We're hoping to receive even more help from people like you," she tells us, "because the $100 million in aid to the contras will almost certainly result in intensified sabotage, more attacks on co-operatives, more displaced people."

The process of resettlement is complex. "There are different situations. Twenty-five percent of the resettled families were moved from the war zones. We went to the communities and explained why they had to move, and gave them what support we could, like trucks so they could take all their belongings with them. They tend to end up living better because they can take those belongings along, which often isn't the case with those families who are forcibly displaced by contra attacks."

Opposition to the relocation campaign has been less than might be expected. Certainly, there has been no repetition of the clumsy and callous relocations forced upon Nicaragua's native Atlantic Coast population during the early stages of the war there. Peasants often find the land they are given in the resettlement areas is five or six times as productive as the dry, stony mountain plots they left behind. According to Marianne, they are also given the choice of farming individually - which is the norm in the widely-dispersed, and thus highly vulnerable, northern settlements - or combining in co-operatives. It's important not to tread on toes if you can avoid it.

"It would be a lie to say that all farmers are good Sandinistas," Marianne notes. "I mean, some of them are with the contras, either by choice or by force. But most of them just want to live in peace, and work - as farmers, not as Sandinistas or contras."

In the two months prior to our visit, the contras had destroyed five resettlement camps. "Sometimes the people say after an attack, 'Why didn't you give us some mortars, some machine guns to defend ourselves? If you had, maybe we wouldn't have had people killed.' It's very sad to hear that, because we just don't have enough of those weapons to go around."

And yet, there has been at least one valuable by-product of these years of suffering and destruction: the changing role of rural women. The situation now is so extreme that it's difficult for men to prevent their partners playing increasingly active and productive roles in the family and community. In Nicaraguan cities - and especially Managua - many women who'd been active in the revolution have been forced back into traditional roles by their menfolk. But for some peasant families just scraping by, machismo is a luxury they can no longer afford.

Karla: "Before, we'd go to co-operatives and the man would open the door, the woman would stay in the background. Sometimes you wouldn't even see her, and if she offered her opinion it was almost as though she had to ask her husband's permission to do so.

"Now that's changing. There are more and more women prepared to speak their own minds without fear." It's a long process, she adds, imbuing women with a new consciousness. But as with the revolution itself, the longer the process continues, the less are the chances of a reversion to traditional patterns of domination and repression.

It makes me think of the people we've met so far, how many of those who've made a strong impression on me - Alma, Anna-Patricia, Karla, Marianne - have been women. There's an aura about them of total commitment that never seems strident or doctrinaire. Perhaps it results from a heightened recognition of the revolution's profound importance - not just to the health of their societies, but to the fulfilment of their own roles within society.

In Jinotega, across a range of hills from Matagalpa, we are due to visit a military hospital which also treats civilians injured in contra attacks. We drive dutifully out, and run smack into some nervous buck-passing while arrangements are checked and phone calls to headquarters made. Eventually it transpires that the head doctor is away for the day, and a tour of the hospital is out of the question.

Our schedule in the area has fallen to pieces, generally and unavoidably. There is no saying from day to day which roads will be safe, and for how long. The morning of our planned visit to a cooperative, the trip is cancelled: there may be mines along the road.

In Region VI, it appears that foreigners are being specifically targeted in contra attacks. Several European aid workers have been killed by mines and in ambushes in the last couple of months: "a matter of bad luck, bad timing and the wrong place," according to an American solidarity worker based in Matagalpa.

The contra leadership's latest trick is passing around copies of weapons permits allegedly found on the bodies of the dead foreigners. In typically scurrilous fashion, this is cited a proof that the foreigners have been co-opted by the vicious Sandinistas into helping with brutal government repression of the peasantry. No weapons have actually been recovered from the corpses, mind you. And what if they had been? Why shouldn't those Europeans have carried guns? After all, the people who killed them did.

In Jinotega, by exquisite chance, we run into a remarkable old man: a 75-year-old Sandinista who fought with Sandino in the guerrilla leader's war against American occupying forces back in the 1920s and '30s. Such living links to the past are cherished in Nicaragua, and this proud gentleman is glad to point out the medal given him by Daniel Ortega, confirming his status as one of the original revolutionary force. He stands ramrod-straight for our photos, clearly basking in the attention.

How did he feel when Sandino was killed? The deep lines on his face contort with remembered rage. "Furious! But I went into hiding, as an opponent of the government. Really! How were my children going to eat? How was I going to send them to school?"

After the Triumph, he was mobilized in a battalion as a fully-fledged member. Any tokenism there, friends, and he'd probably have kicked some young upstart ass. I tell him: "I reckon if we put two old-timers like you and Ronald Reagan together in a room, we could be pretty sure who'd come out." When it's translated, he nods emphatically and gives a vigorous thumbs-up.

Alejandra Picado Martínez remembers. "On a day like this, around midnight, we heard a bomb go off. I was a little sick at the time; I heard the bomb and went back to sleep. About half an hour later I woke up again and heard the kids moving about. I wondered what was going on. One of my sons came in and told me that if anything happened, he would be down at the end of the block. So at four a.m. I got up and went around the various rooms to see where my children were. None of them was there. They'd all gone off to take up their positions. That was Sunday morning. On Monday, the planes began to bomb the city. They bombed every day for nineteen days, all day long."

Clementina Rodríguez remembers. "My children were part of the Revolutionary Students Federation at the time, and I was involved in the group that later became the Association of Nicaraguan Women. Our role was to try to organize more women for the struggle, and to prepare food and medicine for the upcoming insurrection. We were hiding guns in our attics too.

"During the insurrection, we intercepted the National Guard's radio communications by stringing wires to our TV antennas. That way we could tell which parts of town they were planning to bomb and give the warning to evacuate. That's maybe the reason there weren't too many casualties from the bombs themselves. And we could hear the Guard over the radio, saying, 'Those sons-of-bitches are pretty good shooters - they're killing us with .22s!'"

Cristina López remembers. "I was supporting my children's activism even though I didn't really know what the FSLN stood for. I began to grasp it when I saw how the Guardia treated youth. They would drag them away in the middle of the night, with no shoes, or naked - just take them away and shoot them. Once, right outside my window, I saw the Guard build a bonfire. They took a kid out and threw him into the fire. That's when I began to understand.

"Today we're organized, we're continuing to support our sons so they can carry on the struggle of all Nicaraguans. I've already had one son killed and I'm never turning back now." A ripple of gunfire punctuates her speech - a signal of some kind, or a celebration - and she smiles. "Thank you all for coming here. Some of you might be a little scared hearing gunfire. I promise you, we're used to it."

Cristina's son was killed fighting the contras. Alejandra's son was killed at San Juan del Rio Coco in April 1979, not long before the Triumph. Since the advent of the war against the contras, the ranks of the Mothers of Heroes and Martyrs have swelled considerably.

The next day, the anniversary of the insurrection, we attend a special mass for the Mothers on the upper level of a ministry building. It's a lovely scene: an open balcony, silver rain falling behind a fringe of tangled vines. The priest, clad in a white cassock with a multicoloured woven scarf, mutters soothing words of comfort and benediction. The Mothers whisper "Amen" and sniffle quietly into handkerchiefs. Afterward, some of them walk around the adjacent gallery with us: row after row of grainy photographs, all the mothers' sons and daughters who fell and continue to fall; ominous spaces left on the walls for the photographs still to come.

We're sitting in the shade of a big tree, sun baking the ground in dappled patches, listening to Rafael Flores. Rafael is president of the Gámez Garmendia cooperative near Estelí: one of the largest and most successful in the region. He speaks in smooth, measured phrases from under his bright blue New York Yankees cap. (Nicaraguans are famous baseball fanatics; we come across an old man on the beach at Corinto spending his afternoon painstakingly scrawling the names of North American teams into the sand.)

I end up taking notes later from someone else in the group. It's just too relaxing here to be diligent. A few flies buzz around; the sun licks at the edges of our shade; and away in the distance there are futile squeals of protest from what will shortly be our pork lunch.

Rafael talks about the revolution. "In 1979, after the third and final insurrection (in Estelí), we began to work in the streets clearing up the rubble. Some of us were saying, 'What will we do now the bosses have gone?' Then we were told that the revolution had triumphed, that land would be given to the peasants. So we thought, let's go out and take some land and farm it.

"We had our eyes on a piece of land that had absentee owners. Fourteen of us went and started to work it. That was August 1979. We got basic tools and a bit of money and advice from the government."

The first crop at Gámez Garmendia was potatoes and cabbage. "It turned out well. We were able to pay back the government, and we made 10,000 córdobas profit." That was a lot of money back then, with a few córdobas to the dollar instead of 1,400. "Before 1979, I'd never even seen what a thousand-córdoba note looked like! When word got round of our success, there were plenty of other people willing to join our co-operative."

"But of course, every year you take your chances. The next year we bought seed from Guatemala that turned out to be bad. Our potato crop failed, and we lost money. Our new compañeros left us, and we were back to the original group of people."

Francisco chips in: a swarthy and amiable man, tough as nails. "I was an ATC (Rural Workers Union) leader, and we were told approach people and tell them about the co-ops, encourage peasants to form them. The idea wasn't new. In the '30s, Sandino and his men had formed co-ops which were eventually destroyed by the Guard, everybody killed. But it's not a simple thing, forming one. It requires real ideological change, asking farmers to work for a larger entity than themselves and their family."

Gámez Garmendia was the first in the Estelí region to receive an official title to its land - third in Nicaragua overall. Eventually the co-operative united with one nearby. Twelve families joined with eighteen others, and since July of this year 18 more families have signed up. "The door's open for more," Rafael says. "People are in favour of co-ops now. They can see the fruits of the new system.

"The counter-revolutionaries have been coming out with all kinds of propaganda crap - saying all the profits go to the government and so on. It's not true. Leaders visit us to exchange information and to give us advice and support, not to tell us what to do. We make our own production and marketing plans. The only thing the government demands is that we be hard workers and responsible."

It's all very smooth and low-key. Rafael laughs. "We're proud to have you here with us, because in the past we would never have had this kind of visit. Before the revolution, only government ministers received visitors. When we had our first delegation, back in 1980, we were actually trembling with nervousness!"

No sign of it now. Rafael and Francisco are proud of the cooperative, and we trot off in groups to explore it a little on our own, climbing the stony hillside where the goats graze. Eric, a cheerful Manitoban, slips into a shady glade with his flute. A few seconds later a rustic melody wafts out over the dales.

Surprise: We've been granted the afternoon off from our hectic schedule. We spend it lounging around, chowing on the cooked remains of Mr. Pig whose tragic fate was audible earlier in the day. Francisco holds court on a stone fence at the shady end of the fields, talking softly about his militia service in the north, about fighting the contras.

He has a really remarkable quiet confidence, cleaning his AK-47, talking of chases and battles and days when he and his compas were ambushed three or four times in succession. "The contras are pretty astute," he says, "and in the mountain zones they have a whole system to manipulate the peasants. But they've never succeeded in their military objectives."

It echoes comments we've heard throughout the trip, always with the same matter-of-fact certainty: the contras are beaten, strategically at least. They're still capable of doing enormous damage, but it's terrorism, not combat. The Sandinista Army's morale has grown and that of the contras has fallen, to the point that serious clashes between the two are now almost unheard of.

The last major engagement was almost a year ago, in La Trinidad, not far from Estelí. Nine hundred contras came down from the hills and shot up the town, wrought some havoc, and retreated. Then the pursuit began. This is the usual procedure. The Sandinistas take no chances with indiscriminate fire in the towns or settlements under attack. Instead, they harass the contras constantly, vengefully, as the rebels race back to their hideouts in Honduras. In the attack on La Trinidad, the contras lost 150 killed, 350 wounded; 60 more surrendered.

With casualty rates like these, the contras' recent actions - blowing up civilian buses with land mines, targeting foreign-aid workers - seem signs of desperation more than anything else. Terrorism is the war of the weak, and the longer it continues in Nicaragua, the less the chances of the contras coming to be seen anywhere as an effective or legitimate opposition force.

It's all very fine, the heat of the day and the long valley vistas. There's Francisco's conversation, and some warm rum flowing through the system. Sometimes you have to pinch yourself and notice just how vulnerable cooperatives like Gámez Garmendia really are: tucked away a few kilometres off the main road, surrounded on two or three sides by lush ranges of hills.

I imagine looking up from my reverie and seeing battalions of blue-clad killers flowing down the hillsides. Then I look back at Francisco, giving a couple of our internacionalistas lessons in assembling his old friend, the AK-47. Francisco has seen a few scenes like that, or something very similar, and he's seen them through. Confidence.

A notice we saw taped up in Estelí bore a quote from Sandinista comandante Tomás Borge. When we run into difficulties, when we are backed into a corner by scarcities, we should think of those who are fighting and spilling their blood, who ask only for the strength of heart that comes from doing one's duty.

And Ulises Gonzalez, an official here in Region I, told us: "Beans, corn, rice, tobacco - but maybe our main product here is courageous people."

Miraflores is an agricultural cooperative a few miles to the north, near the border with Jinotega Province. It has been attacked by contras four times, beginning in 1983. The couple of hundred workers there have been offered relocation to a safer zone. For the most part, they've refused, though the majority of women and children have been removed.

In the May attack, the contras used M-79 grenade launchers and fragmentation grenades. One worker, an architect, was caught in one of the defensive trenches ringing the perimeter. He had his legs blown off by a grenade. He didn't die right away. The contras set about eviscerating him with bayonets; then they castrated him and left him there to die slowly. Two small children hiding in a room were blown apart by a grenade. When Scott, our translator, visited the scene three months later, the room had been whitewashed, but a few dark pellets of dried blood were still visible on the ceiling.

Earlier in the day, before our visit to Gámez Garmendia, we had stopped off at El Portillo, a cooperative on the outskirts of town. There, we had seen army helicopters thrumming busily overhead. On the way back into town, we were told that Miraflores - fifteen kilometres and two or three hillcrests away - was once again under attack.

We kept our eye on the papers, but nothing appeared in Barricada or El Nuevo Diario. The action seems to have been more of a nip at the cooperative's defences than anything else, a warning of things to come. Or it may not have happened at all. Like any country in wartime, Nicaragua is alive with unsubstantiated rumours.

It is described to us by Eduardo Baéz; and in Eduardo's energy and enthusiasm I find what may be my most vivid imagine of Nicaragua. You can weep for all the opportunities lost and crushes, the immense obstacles, the way Reagan's war is bleeding sectors of Nicaragua - health care, education - when all the world should be rejoicing at the advances made in those fields. But then you can talk with Eduardo, and see what is still possible on a wing and a prayer in this country, with nothing but ideas and commitment and hard work to tide you over.

"Popular education," Eduardo tells us, "is a totally different concept from traditional education. The traditional form depends on the stereotypes of all knowledge being found in books, and teachers being the repositories of all that's knowable."

He sits on the counter in an office at Estelí's adult education centre, swinging his legs rhythmically back and forth like an eager schoolkid, talking in rapid-fire English. Eduardo studied in the States back in the early '70s, "back in the good times." He still keeps the blue jeans and long hair from that era.

"We're developing a concept of knowledge not as a passive thing, but as the capacity one has to understand reality in order to change it. It's really a very subversive concept of education. If you want to change a building, but don't understand its structure, you may end up painting the building, but you won't change it. ... The challenge of popular education is to take school out of the classroom and into the community, into daily life and reality - work, the family, society.

"This project in Rio San Juan has involved all the teachers in the region, unions, women's organizations, everybody. It's organized by the people at a local level, not under centralized control - and all this in a war zone that's also one of the most underdeveloped regions of Nicaragua. The people are learning things related to real life - health, hygiene, defense, social problems, community organizing, and so on."

He grabs an alphabetization manual. "First lesson: 'Education Is Our Right.' Second lesson: 'The Kid Has Diarrhoea.' Then comes reading and writing practice. The objectives are integrated, you see. Lesson three: 'He Brings Down the Potato' - a chance to discuss food, nutrition, and so on." Eduardo flips through the manual rapidly. "Here: 'The Kid Sucks the Tit.' Breast-feeding. The language is the people's language, not some scientific jargon that would mean nothing to them."

What about criticisms of the political content of Nicaraguan textbooks? "There's not a single sentence like 'Long Live Sandino' in this textbook. That was a mistake we made in our first textbooks, trying to inculcate a revolutionary ethic and so forth. We finally realized that sort of thing has to develop naturally. It can't be forced. There's things occasionally like adding up the number of grenades in the picture, sure. It's reality for people here! You're not going to be adding apples and oranges when grenades are falling on your roof."

Not surprisingly, teachers of popular education have been one of the contras' main targets. Dozens have been killed or kidnapped. The alternative offered by the counter-revolution is revealing. A doctor at a neighbourhood clinic in Managua told us that in backward areas like Rio San Juan, health workers have met resistance from campesinos who have been exposed to contra propaganda. The contras tell the peasants that health workers who comes with needles are planning to inoculate them with communism.

"Nineteen eighty-seven is going to be the most complicated and difficult year we've had since 1979. There's the legislative elections in the States, elections in several Western European countries - a whole range of imponderables. We still haven't seen the results of the $100 million in contra aid (passed by the U.S. Congress in Summer 1986), or of the $300 million allotted by the CIA. But everything we've seen leads us to conclude that still further military aggression will be carried out. The international scene is complex and deteriorating. Only our enemies seem united. The threat of direct U.S. intervention is still grave.

"We, and those working in solidarity with us, are going to have to find a way to get us through another year. There's a big drive underway to make the contras look like a legitimate opposition; you in Canada are going to have to counter that in your own work. For our part, we can only work to make the American public understand how costly, on all levels, direct U.S. intervention would be. What it would mean for hundreds of thousands of Americans to be killed; the kind of historical consequences there would be for all Latin America."

It's sobering. Diana, an Ottawa volunteer, asks: "Do you think the U.S. pressure is killing the Nicaraguan revolution?"

Anna-Patricia gathers her thoughts for a moment. Then: "Don't imagine that the revolution is the economy. The revolution means holding guaranteed power. This small territory of ours is still in our hands, and I think the revolution is more vibrant, more alive than ever. We have to admit that the U.S. intervention is causing us great, perhaps irreparable damage. But those who are making the decisions here are the people themselves, the organized people and the FSLN. The day the people no longer support the revolution, then we'll have failed."

The day is not yet.

Sandino Airport, one last time. The young customs official hands my passport back to me. "Gracias," I say, "y viva Nicaragua libre." He grins broadly. "Gracias. Adios."

On our way back to Canada, we spend a day in San José, Costa Rica. There are banks and Pizza Huts; there are policemen in green fatigues, with pistols and billy clubs, who return smiles with glowers. The range of trivial consumer goods in the stores is dizzying, almost overpowering after the material paucity of Nicaragua. It is Costa Rican National Independence Day. The flag-laden vans racing through the streets are obviously government-hired, and the cheers in the street sound more than a little ragged.

La Prensa, the reactionary rag shut down by the Sandinistas a few months ago, has a new life as Nicaragua Hoy, publishing as an insert to the conservative La Nación. The masthead features an outline map of Nicaragua, tangled in barbed wire.

"I can't even play the thing," he said, tapping the bleached lid [of the piano] with his elegant fingers. "I tell myself I will one day; I'll take lessons or get a book. But I don't really care. I've learnt to live with being half-finished. Like most of us."Maybe, just maybe, revolutions are getting better.

- John Le Carré, A Small Town in Germany

Think about it for a moment. The French Revolution, 1789: limited bourgeois origins, then chaos, carnage, and a tyranny as cruel as the one it overthrew. The Russian Revolution, 1917: a country dragged kicking and screaming into the twentieth century, but by a fairly narrowly-based urban intelligentsia and proletariat, and with millions of disgruntled peasants killed in the process. The Chinese and Vietnamese Revolutions, 1949-54: the developing unity of city and countryside against corrupt, foreign-backed despotisms; considerable material gains, tempered (at least in the Chinese experiment) by massive violence and present-day stagnation. Cuba, 1959: the advent of a strikingly robust socialist culture, a standard of living unheard-of in the region, but a pattern of political repression that is by now all too familiar.

Nicaragua, 1979, seems different. The reasons are manifold, and would take a great deal longer than two weeks to appraise properly.

There is, first, the nature of the revolution itself. At least in its final stages, it marshalled a broad cross-section of the labouring and business classes to overthrow the Somoza dictatorship. For idealistic and pragmatic reasons, the Sandinista leadership has found it worthwhile to encourage "responsible" pluralistic thought and discussion. (Those who point to increasingly strict limitations on this pluralism ought to remember that the civil-liberties record of North American and European countries in wartime is hardly spectacular.) Indeed, many Nicaraguans would disagree with Sandinista policy, without necessarily questioning the motives and sincerity of that policy.

Related to this, and it seems to me every bit as important, is the growing alliance between the revolution and progressive Christianity. Entre cristianismo y revolución, no hay contradicción! Between this Christianity and this revolution, there is no contradiction.

This isn't to deny the very real degree of polarization in Nicaragua's church. It is merely to note that, where politics and religion have fused in Nicaragua, they have formed a hybrid world-view and aesthetic that, in some ways, is to previous revolutions as the Iron Age is to the Bronze Age.

This thought occurred to me while speaking with a woman in one Managua barrio who was organizer of a base Christian community. She spoke with fervour of the movement against Somoza and the role Christianity had played in mobilizing and motivating people to overthrow the dictatorship. She showed us the dusty graveyard for the dozens of neighbourhood residents killed in the revolution. And later that night we went to a party: a raucous affair at which this very sincere, very committed middle-aged woman let loose with lusty renditions of well-known revolutionary songs. She followed that up with a rather suggestive tune whose general thrust was conveyed with a campy strut that would have made Mae West blush. Politics, Christianity, and unabashed good times: in one evening, in one person.

Faith, like any catalyst for human progress, flows underground. It is not something that can be tapped in a brief visit, and I resist drawing firm conclusions. But the words of Conor Cruise O'Brien bear considering. Writing in August's Atlantic Monthly, he notes:

You can actually feel around you in Nicaragua something going on that you know can't be switched off, either from Washington or from Rome: that most intractable thing, a new kind of faith. ... I think it would now be more accurate to speak of Sandinismo as a faith rather than an ideology. It is the most formidable kind of faith - the kind that is emotionally fused with national pride. And this kind of faith is now alight in every corner of Latin America. ... It is true that in the past the United States has been able to intervene in Latin America repeatedly and with impunity. But things are a bit different now; there is a new spirit around. In particular, the new alignment of el Dios de los Pobres (the God of the Poor) and la patria - faith and fatherland - is shifting the balance.O'Brien adds that "The Sandinistas sincerely pride themselves on their magnanimous and positive approach to religion and on having altogether abandoned the doctrinaire hostility to all religion which has hitherto been common to all revolutions claiming any degree of Marxist inspiration." Whether this new revolutionary alignment will prove strong enough to withstand the superpower assault is open to question. But its energy, resilience, and potential are all beyond doubt.

Real abuses have occurred - and still occur - in Nicaragua. The Sandinista revolution, under fire, remains incomplete. Yet against all odds, and contrary to my expectations, the Nicaraguans we met last month showed no inclination to settle for that as an end-product. They showed even less desire to back-pedal in a fashion that Ronald Reagan and his counter-revolutionary clique might find halfway acceptable.

Who, after all, wants to live a half-finished life? Patria libre o morir.

Created by Adam Jones, 1998.

No copyright claimed for non-commercial use if source is acknowledged and notified.

adamj_jones@hotmail.com.

Last updated: 10 October 2000.