I arrived by plane from Mexico City after a real "Keystone Kops" day of travelling. I should have realized I was in for a few bloopers when I stepped off the public bus at the bus station in Guadalajara, stumbled, and ripped half the sole of my shoe off. Not much opportunity to do anything about it, since I had a bus to catch - so I patched it up with masking tape, and settled in for the seven-hour overnight ride to the world's biggest city. Got there around 3:30 a.m., waited for the metro to open at five, and then headed straight to the airport, where I confidently marched up to the LACSA (Costa Rican airways) window to present my ticket, only to be told: "There's been some mistake. This flight hasn't existed for eight months." What!! I'd reconfirmed it with the LACSA office in Guadalajara three days before! Before too long, no fewer than half a dozen other travellers had turned up with tickets for the same non-existent flight. What was really amusing was the way the LACSA rep made out that it was somehow my fault (because I didn't have a phone number for them to contact me, to inform me of the error), or that of my travel agency (and all the other travel agencies who'd written tickets for the hapless travellers stranded along with me). Anyway, the upshot was not too severe. I was transferred over to a Copa (Panamanian airlines) flight, and although it left six hours after mine was due to, it was direct to Managua, with an arrival time only an hour later than my originally-scheduled flight (which had a long stopover in Costa Rica - however strange this may seem if you look at a map). I kept myself busy chatting up a nice Colombian girl who was headed to Medellín - pronounced "MedeJIN" in the local accent, in case you're curious.

The flight itself was lovely. From the south of Mexico onwards, we basically followed the coastline, along the Pacific coast of Guatemala, over El Salvador (blink and you'll miss it, from 30,000 feet!), and into Nicaragua. Almost an unbroken chain of rugged mountains and active volcanoes, then Lake Nicaragua (second-largest in Latin America, and the only lake in the world with freshwater sharks), and finally Managua, a low-slung city of 900,000 or so, with the white tower of the Bank of America building visible from a good fifty miles away. This was the only major building in downtown Managua to survive the great earthquake of 1972 - more on that later.

We landed at Managua International Airport, which is about the size of Kelowna's, and immediately I was assailed by the muggy tropical air that soaked my shirt through. The customs officer asked for U.S. $5 for the entry permit (standard procedure), and I indicated that I would have to pop over to the money-change window first, because I only had Mexican pesos. Memo to all those contemplating a trip to Nicaragua: BRING U.S. DOLLARS! Nothing else works! It was the only currency accepted at the change window. Why I didn't prepare for this, after three previous trips to Nicaragua, is anybody's guess. But I was left floundering around penniless, until finally the customs guy stamped my passport without even charging me the entry fee, and the lady at the change window gave me the address of a bank that was still open, and where I could get an advance with my Visa card. Then I had to negotiate with a taxi driver to take me to the bank "on spec," wait while I changed some money, and carry me on to my destination in Colonía Centroamerica. As I left the bank, newly rich in Nicaraguan cordobas, the skies opened and one of those amazing ten-minute Managua downpours hit, turning the roads to rivers and forcing the driver to negotiate every intersection with great care lest he flood the engine.

But even in the middle of the downpour, I was feeling some of the energy and strange beauty of this city seeping in - something to do with the casual cheerfulness of the people at roadside, the heavy, sultry air that always lets you know you're alive, the colourful political graffiti on every wall, the lushness of the tropical foliage. The taxi driver (a nice guy, César Chavez by name - like the Mexican-American union activist) dropped me at the end of my little anden (alleyway) in the middle of Centroamerica. I was meant to pick up keys from "Doña Flor" a little further down the anden, who, I had been assured, was always home ... except she wasn't when I rang. I was just beginning to imagine a further sweat-and-possibly-rain-soaked expedition to one of the guest-houses downtown, when Doña Flor came back from a shopping expedition, all smiles. Two minutes later I was pushing open the door to Liz's place and making myself at home.

Didn't have energy for much more than that last night, as you'll appreciate, but I did manage to partake of two of the great pleasures this city has to offer. The first was a cold bottle of Victoria beer, which for my money (about 50 cents) is the best pilsener outside the Czech Republic - if you check the "Travel Page" of my Website you'll see it listed as one of the "great beers in countries where you wouldn't expect to find great beers"! Number two was Colonía Centroamerica itself. It's nothing special - just a middle-class Managua 'hood, all single-storey dwellings with clusters of much poorer tin-and-wood shacks around the edges. But life in Centroamerica is always visible from the street - it's so hot and muggy that people keep their doors and windows wide open to catch the breeze, and then pour out into their gardens and onto the sidewalks to chat, eat, and listen to music. I'm writing now (mid-evening) to the accompaniment of cicadas' song, the chatter of TV, kids fooling around with a football ... a few houses down is the "pulperia" of my anden - a house that the tenants have turned into a corner-store, retailing cold beers and other essentials of life; and in the morning I can look forward to a succession of door-to-door marketers calling out their wares: newspaper vendors, purveyors of agua dulce ("sweet water," that is, coconut milk), mangoes, avocados, tortillas, insecticide ...

Only one thing about Centroamerica: if you're walking around in the evening, be careful - it's dangerous. Not because there are criminals out to do you harm, but because it's nearly pitch-black in most parts of the neighbourhood, and the infrastructure of sidewalks and drains leaves a little to be desired. Last night I was strolling along the sidewalk and glanced down just in time to see a yawning hole, around four feet square and as many deep, with a pool of grim-looking water of unknown depth at the bottom. More than a few people have broken limbs as they suddenly disappeared beneath the level of the sidewalk ...

Today, my first full day in Managua, I spent gathering supplies at the local market. Word must have got out about my flapping shoe, because there was a guy on the street-corner selling Super Glue for a dollar a tube, and now I am properly shod again! In the afternoon we had another pelting rainstorm; and after it had abated, I went on a long stroll along the Carretera Masaya, one of the main roads leading out of town. The first stop was the offices of Barricada, the newspaper that I came down to study in 1991 and again in 1996, and which died a mostly-unlamented death in February of this year. (You can read a quick summary of its history at <http://www.interchange.ubc.ca/adamj/diss.htm>.) I'm back here, for the most part, to investigate the circumstances of Barricada's death - interviews and archival research are the focus. To my surprise, the gates to the building were open, and I went in for a stroll - rather a sad little look-see, since the building I'd spent months working and researching in on past visits is now a derelict shell, and soon to be torn down.

From there, I strolled down to the University of Central America, the journalism school to be precise, where I left a note for one of my hoped-for interview subjects, who teaches there. Then it was down to Plaza Espana and Barrio Marta Quezada - my base of operations in 1996, and the place where most backpack travellers stay while they're in town. I passed on the way the brand-new McDonald's - the first in Nicaragua since the revolution of 1979 sent many foreign capitalists fleeing. The return of McDonald's has been hailed in the local press (as I know from a clipping Liz left for me) as a sign of Nicaragua's "regeneration" - but since all of about five percent of the population can probably afford to eat there, I'm not so sure, personally. There has certainly been a proliferation of restaurants, boutiques, and spiffy cars in the two short years since I was here last - but behind these facades, the poverty seems every bit as grim as on previous visits. The new (well, post-1996) president, Arnoldo Alemán, is pretty much a fascist of the old school, and he and his brazenly corrupt team are not likely to do much to alleviate the situation.

But more on politics later. Zapa and her offspring are now curled up snoozing by my computer, and I'm beginning to think (after a couple of Victorias) that they have the right idea. I still have some shut-eye to catch up on after the travelling of the last couple of days; and there's no need to try to tell you everything all at once.

Part of it has to do with the fact that Managua, unlike virtually any other Latin American city of its size, is reasonably uncongested. There's a lot more traffic now than when I first came here, in 1986; but because life is lived in the alrededores - the suburbs - it moves fairly freely along the main arteries. This has very little to do with intelligent urban planning, and a lot to do with a natural disaster: the earthquake of December 1972. In addition to killing upwards of 20,000 people, that quake levelled virtually the entire downtown core, which used to be strung along the shore of Lake Managua. I was "downtown" today, for reasons to be mentioned, and was struck again by the empty-lot feel of the whole area. Most of it is still overgrown rubble and shells of buildings - although, because this is Managua, there are people living in those buildings, hanging out their washing on the second floor of an edifice with spider-web cracks all through it, kids playing on the abandoned stairwells. The main cathedral of Nicaragua was one of the casualties of the quake and still stands as a cracked facade. The former mayor of Managua, now president, Arnoldo Alemán decided after 1990 that the city needed a new grand cathedral, and so he built it away from the fault-line ... although, despite a cost of some $100 million, it's not much of an improvement. For one thing, it must be the ugliest building in the western hemisphere - it looks like a nightmare combination of a Moorish castle and a wedding-cake. Secondly, the paper today reported that serious cracks have just become evident in the facade - leading people to wonder whether it will last five seconds in the next big quake, which everybody expects. (There's a tremor every few weeks here; I'll let you know if one hits while I'm in town.)

Anyway, slowly, slowly, the downtown core is being "regenerated," which basically means that Arnoldo has decided on another mega-project - a presidential palace currently under construction. About the only other thing standing, apart from the Bank of America building, is the National Palace, where I was today. This was the building seized, in 1978, by the Sandinista rebels, in one of the greatest guerrilla actions ever staged - they disguised themselves as guards of the then-dictator, Anastasio Somoza, strolled in as though they owned the place, and sequestered every deputy in the National Assembly who'd bothered to show up for work that day. By doing so, they won the freedom of most of the top Sandinista leaders in Somoza's jails, and flew off with them to Cuba - with tens of thousands of Managuans lining their route to the airport, to cheer them on!

Anyway, the palace was quickly repaired after the '72 quake, and today, thanks to a generous grant from the Taiwanese government, it's home to the National Library. (Nicaragua is one of the few countries in the world that still recognizes Taiwan as the legitimate ruler of all China. In return, it's welcomed a string of Taiwanese investors, who've set up a number of sweatshops failing to meet the most minimal labour standards, and who have also cheerfully headed into the forests of the Atlantic Coast to strip the country of its precious hardwood resources.) The library is still in the process of being unpacked, but it houses a fairly complete collection of Nicaraguan newspapers - hence my visit. On past trips I used the Barricada library for my research, but of course that's no more (I could swear some of the bound volumes of back-issues that I plowed through on previous occasions are the very same ones now stacked against the walls of the National Library. Well, they'd have had to do something with them after Barricada closed, I guess). I'd already had a very successful start to my first full day of research - tracked down Alfonso Malespín, a former Barricada reporter, at the University of Central America and sat him down for an interview, in which he explained a lot of what I've been missing from the last couple of years of Barricada's history. (He also agreed to proof the book manuscript I'm finishing up about the paper - the more well-informed types I can find to do that, the fewer egregious errors there'll be in the finished product.)

I also stopped off to try to see Sofía Montenegro, with whom many of you will be familiar; but the office of the research organization she works in has moved. The National Palace being in the neighbourhood, though, I decided to stop in - and ended up spending a fascinating four or five hours leafing through stacks of newspaper back-issues, with a hot breeze blowing off the lake and through the windows to rustle the pages of my reading-matter. For some of you this will probably seem the most boring afternoon imaginable, but I was in my element. I pulled a lot of important stuff (important to me, anyway) from the late 1997 issues of Barricada, when its fatal crisis hit; and more good stuff from the only surviving leftist paper in town, El Nuevo Diario, which had some pretty solid coverage of the final closure of Barricada and the journalists' protests that surrounded it. I stayed to close the place, with the librarian drumming her fingers ostentatiously on the table to let me know my time was nearly up; and headed home with the sun setting over the hills and Managua glowing a spectacular burnt orange. (Another reason I love the place: I'm a sucker for sunsets.) Of course, getting home meant riding one of the city's famously-crowded buses, in this case the no. 119, known far and wide as "The Managua Massage." I actually thought I had two square feet of standing room to myself when I boarded - and then I saw the space was empty because somebody had vomited all over the floor. Oh well.

Now I'm back at Liz's place with a long weekend ahead - which might explain why neither Sofía Montenegro nor Carlos Fernando Chamorro (son of former president Violeta Chamorro) was home when I tried to call them. These two were the leading lights of the old (pre-1994) version of Barricada, and my two closest contacts on previous visits. It's actually a pleasure to be able to roll into town without having to sit them down for formal interviews - I'm looking forward to just getting together, knocking back some rum, and talking about old times and new, with a few notes jotted down whenever they divulge some interesting gossip. (Ninety percent of Nicaraguan politics is gossip, anyway.) Looks like I'll have to try to get them next week, at which time I'll also be heading back for another couple of days in the National Library. I did manage to get hold, last night, of Daniel Alegría, who used to edit the international edition of Barricada and actually edited the daily edition for all of three days in 1994, after Carlos Fernando Chamorro was kicked out of the paper by the ortodoxo ("orthodox," i.e., more hard-line) faction of the Sandinista Front. Then he, along with Sofía Montenegro and about 80 percent of the former staff, split rather than work under the new bosses, who proceeded to run the paper into the ground economically and professionally.

Daniel is an amazing character - has an American father, so he speaks English (or rather American) like a native; about my age, though eternally boyish in looks; and with quite a remarkable background. He moved back to Nicaragua after the revolution in 1979, and quickly joined the special forces of the Ministry of the Interior - he's never confirmed this to me, but several others have told me that among other duties, he was assigned to infiltrate the ranks of the Contra rebels who terrorized Nicaragua (under the sponsorship of Ronald Reagan) in the 1980s. He lived to tell the tale, and moved on to become personal bodyguard to Tomas Borge, Minister of the Interior under the Sandinista revolutionary government. Borge in 1994 was the one who led the overthrow of Carlos Fernando Chamorro at Barricada and installed himself in Chamorro's place! Which explains how Daniel came to edit the paper for a few days in October 1994, before he threw up his hands in disgust and split. He now works at Oxfam, and seems happy with his job. He's also become something of a cyber-junkie, and compiled a Web page for himself and his interesting family, which if you read some Spanish you could check out - <http://www.oxcamex.org.ni/cuentos>. Daniel is headed to the fancy resort of Montelimar for the weekend, but is back on Monday, when we'll be getting together for lunch and a nice chat.

Thanks to my conversation with Alfonso Malesp&237;n, I also have leads on the whereabouts of several other Barricada alumni whom I'll be looking to track down next week. Now, however, with the percussive sound of mangoes falling onto my tin roof (yet another reason I love this place), Zapa has curled up by my computer and is demanding some attention. Since I haven't been around all day, I kind of owe her. Ciao for now!

The Sandinista Front was formed in 1962 to oppose the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza, third (and fortunately last) in a family line who ruled Nicaragua since the U.S. Marines ended their most recent occupation of the country in 1934. The first Somoza was America's man ("He may be a son-of-a-bitch, but he's our son-of-a-bitch," as Franklin D. Roosevelt famously put it). Somoza had Augusto C. Sandino, who'd opposed the U.S. occupation with a protracted and eventually successful guerrilla war, rather treacherously bumped off; and so when the rebel movement against the family dictatorship arose in the early sixties, they modelled themselves after Sandino - hence, "Sandinistas." Only one of the founding members of the Sandinista Front is still alive - Tomas Borge, the guy Daniel Alegría served as bodyguard. Until as late as 1975 or 1976, the movement was tiny, limited to student supporters in the cities and a couple of hundred guerrillas in the mountains. But the dictatorship began to waver in 1972, after the earthquake destroyed Managua: Somoza appropriated a lot of the foreign aid and made sure the companies that he and his families owned profited most from the reconstruction. That alienated a lot of the middle and upper classes as well as the poor, and a multi-class coalition began to form against him. In 1977 and 1978, the Sandinistas leapt to the forefront of Nicaraguan politics with spectacular actions like the seizure of the National Palace, already mentioned. In 1978, Somoza had Pedro Joaquín Chamorro assassinated: he was the editor of La Prensa, the major opposition daily, and also the father of Carlos Fernando Chamorro, who went on to edit Barricada and be interviewed (more often than he probably wished!) by yours truly. Pedro Joaquin's rather glum-looking features, incidentally, now adorn the Nicaraguan 50-cordoba bill. I wonder if there's any other journalist in the world who's similarly memorialized.

In 1978 and 1979, the Sandinistas organized a series of urban and rural insurrections that forced Somoza to divide his forces, weakening his resistance. It's estimated that about 50,000 Nicaraguans died in the final rebellion of 1979 - the equivalent of around half a million Canadians, proportional to population. Finally, on 17 July 1979, Somoza fled the country to Paraguay, where, happily, he was blown up by a bazooka wielded by a Sandinista hit-squad in May 1980. The Sandinistas entered Managua on 19 July - that is, exactly nineteen years ago today. They held power throughout the 1980s, winning free elections in 1984 and losing them in 1990, when they turned over the government to Violeta Chamorro - yep, the wife of that murdered editor Pedro Joaquín, and mother of my interview subject Carlos Fernando. Ever since, July 19th has been celebrated as a national holiday - but no more, apparently. Our friend President Alemán has decided that the celebration only serves to bolster the Sandinistas as the opposition force they are today. So beginning next year - the twentieth anniversary, no less! - it'll be just another day, at least as far as the government is concerned. On the other hand, the fact that 70 percent of the adult population of Nicaragua is unemployed means that the large majority don't have work to take the day off from anyway. So I fully predict that there'll be tens of thousands of people in the Plaza de la Revolucion next year - just as there were today.

I rose early to be sure of catching the celebrations from the beginning, and caught a bus downtown, joining hundreds of people who were walking the last half-mile or so to the Plaza. Picked myself up a nice red-and-black Sandinista scarf for half a dollar (the Sandinistas borrowed the flag from the original Sandino, who took it, in turn, from the anarchist forces in the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s). I also had my red T-shirt and black cycling socks on, so I blended right in - yeah, right! Actually, I had to put up with friendly cries of "Chele!" (the Nicaraguan equivalent of "Hey, gringo!") for most of the morning.

To be honest, I was somewhat ambivalent about the politics of the occasion. I was a very staunch supporter of the Sandinistas during the 1980s, as most of you know - visited Nicaragua for the first time at the height of the revolution, in 1986, and recorded my impressions in a long article that's now lodged on my Website, at <http://www.interchange.ubc.ca/ adamj/nica1.htm>. But after their 1990 election defeat, which nobody expected, the Sandinistas entered a period of deep crisis and internal division - basically the split between the moderates and the hard-liners that I hinted at earlier in this diary. Among the "moderates" were most of the staff of Barricada, which is why they weren't too popular with the hard-liners, led by the former Nicaraguan president (1984-1990), Daniel Ortega.

To

present it in such ideological terms doesn't really cover the whole story,

though. In a lot of respects, what's happened since 1990 is the consolidation

of a more traditionally Latin American-style party around the personalist

rule of that same Daniel Ortega, who once again contested presidential

elections in 1996, and once again lost. I'm unhappy with the way the staff

at Barricada were so vindictively and summarily (though not violently)

treated by the "orthodox" bunch; I also have deep doubts about Ortega these

days. If I were a Nicaraguan, I'm not sure I'd even vote Sandinista anymore

- and I never thought I'd hear myself saying that. But I don't see any

prospect for a renewal of the party until the older generation of leaders

leaves the scene, and some fresh talent comes to the fore. Nicaraguans

as a whole have an antipathy towards re-electing anyone who's already served

as president: it's too reminiscent of the way the Somoza dictatorship used

to run things, perpetuating a narrow clique in power seemingly forever.

Beyond that, Ortega's come under a new cloud in recent months, since one

of his step-daughters - by his longtime companion, Rosario Murillo - announced

that he had sexually abused her for years as a child and adolescent. The

allegations are unproven, and Ortega won't be tried on them (he won election

as a deputy to the National Assembly in '96, which gives him parliamentary

immunity); but there's no obvious reason I can see for his step-daughter,

Zoilamerica, to be fabricating the charges, so they're disturbing to say

the least.

To

present it in such ideological terms doesn't really cover the whole story,

though. In a lot of respects, what's happened since 1990 is the consolidation

of a more traditionally Latin American-style party around the personalist

rule of that same Daniel Ortega, who once again contested presidential

elections in 1996, and once again lost. I'm unhappy with the way the staff

at Barricada were so vindictively and summarily (though not violently)

treated by the "orthodox" bunch; I also have deep doubts about Ortega these

days. If I were a Nicaraguan, I'm not sure I'd even vote Sandinista anymore

- and I never thought I'd hear myself saying that. But I don't see any

prospect for a renewal of the party until the older generation of leaders

leaves the scene, and some fresh talent comes to the fore. Nicaraguans

as a whole have an antipathy towards re-electing anyone who's already served

as president: it's too reminiscent of the way the Somoza dictatorship used

to run things, perpetuating a narrow clique in power seemingly forever.

Beyond that, Ortega's come under a new cloud in recent months, since one

of his step-daughters - by his longtime companion, Rosario Murillo - announced

that he had sexually abused her for years as a child and adolescent. The

allegations are unproven, and Ortega won't be tried on them (he won election

as a deputy to the National Assembly in '96, which gives him parliamentary

immunity); but there's no obvious reason I can see for his step-daughter,

Zoilamerica, to be fabricating the charges, so they're disturbing to say

the least.

Nevertheless,

the Sandinistas remain the largest political party in Nicaragua and the

main opposition force - and the turnout they were able to muster at the

Plaza today was impressive. That's all the more true when you consider

that this year's celebration of the revolution almost didn't happen, if

you believe a couple of the local newspaper reports. The Sandinistas are

nearly broke (one of the reasons Barricada died an ignominious death

earlier this year), and apparently they had to pass the hat among the wealthier

members of the party to raise the $35,000 or so required to hold the fiesta

in the Plaza. None of this, though, seemed to matter much to those who

showed up. They were definitely in a partying mood, as evidenced by the

fact that quite a few people were reeling drunk at 9 a.m.! I'm bad at estimating

crowds, but in the past couple of years these gatherings have drawn about

50,000 people, and I'd be surprised if it was much less than 40,000 today.

Naturally, the people selling beer, peanuts, plastic bags full of drinking

water (something I've only ever seen in Nicaragua), and the like were having

a field-day. Under the burning mid-morning sun, even I relented and knocked

back a cold Victoria or three. For a while a band was playing - not a very

good one, though quite a loud one; the music was punctuated by a couple

of rather predictable speeches and cheers of long-live-this-and-that.

Nevertheless,

the Sandinistas remain the largest political party in Nicaragua and the

main opposition force - and the turnout they were able to muster at the

Plaza today was impressive. That's all the more true when you consider

that this year's celebration of the revolution almost didn't happen, if

you believe a couple of the local newspaper reports. The Sandinistas are

nearly broke (one of the reasons Barricada died an ignominious death

earlier this year), and apparently they had to pass the hat among the wealthier

members of the party to raise the $35,000 or so required to hold the fiesta

in the Plaza. None of this, though, seemed to matter much to those who

showed up. They were definitely in a partying mood, as evidenced by the

fact that quite a few people were reeling drunk at 9 a.m.! I'm bad at estimating

crowds, but in the past couple of years these gatherings have drawn about

50,000 people, and I'd be surprised if it was much less than 40,000 today.

Naturally, the people selling beer, peanuts, plastic bags full of drinking

water (something I've only ever seen in Nicaragua), and the like were having

a field-day. Under the burning mid-morning sun, even I relented and knocked

back a cold Victoria or three. For a while a band was playing - not a very

good one, though quite a loud one; the music was punctuated by a couple

of rather predictable speeches and cheers of long-live-this-and-that.

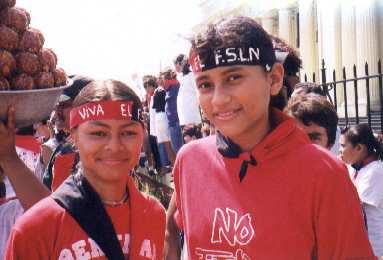

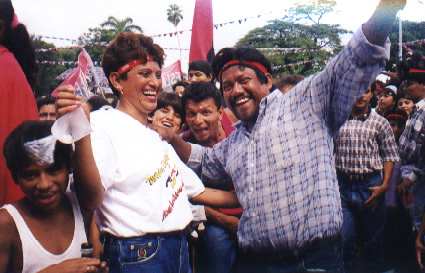

For my part, I wandered around and through the sea of red-and-black flags and similarly-painted or -bescarved people, snapping away like mad with my trusty Olympus. Nicaraguans are notorious clowns whenever there's a camera in the vicinity, and that, combined with the freely-flowing alcohol, made for some really great people shots, I think. It was also a very young crowd, somewhat to my surprise - although maybe it's not too surprising when you realize that youth are disproportionately targetted by a lot of the social and economic difficulties in the country these days, and are anxiously looking for someone to lead them out of the nightmare. Hence those of you who see the photos will notice a disproportionate number of little babies clad in the rojinegro (red-and-black), as well as a few nubile young women. Sorry, couldn't resist - photo-taking's always a great chance to strike up a conversation!

About an hour into the festivities, Fiona showed up. She's a friend of Liz who's been here for the last couple of years, working first with an Australian organization and now with an Irish one. I have a lot of admiration for those foreigners who've continued to come to Nicaragua to do important and much-needed social work, even though the country isn't as trendy as it was during the 1980s. We strolled around together and chatted. I asked her what she liked about living in Managua, and her thoughts bore a passing resemblance to my own: she enjoys the easygoing, no-frills attitude of the people; and the way that few rules exist, while those that do can be bent! The climax of the celebrations came with speeches by Tomas Borge - the surviving founding member of the Sandinista Front and former Barricada director - and, last but not least, Daniel Ortega, who got a rapturous greeting from the crowd. Obviously he still has a lot of fans. Fiona and I got close enough for me to get a snap or two, and then decided to abandon the crush and the blazing heat while Daniel was still speaking, before the other few dozen thousand people in the square decided to do so. We caught a taxi back to her house, ate cheese-and-Marmite sandwiches, and fooled around with her new computer for a while. Then I sauntered home through a quite magical and refreshing sun-shower - rain like diamonds out of a nearly clear-blue sky. That was my Sunday. Beats hell out of going to church.

Any of you who haven't met Sofía yet and would like an introduction to this remarkable lady can check out the long excerpts from "'A Woman and A Rebel'" on my Website, at <http://www.interchange.ubc.ca/adamj/Sofía.htm>, and the briefer profile of her in part two ("Four Voices") of my feature piece, "Nicaragua, 1991: After the Earthquake," <http://www.interchange.ubc.ca/adamj/nica2.htm>. As was typical of many Nicaraguan families in the years leading up to the 1979 revolution, Sofía found herself estranged on political grounds from many of those nearest and dearest to her. We in North America, with our tradition of rebelling against our parents, sometimes have difficulty grasping just how family-centred politics was in Nicaragua for the better part of 150 years. When the Sandinistas came along to drive divisions down the middle of many families, it was in its own way one of the most revolutionary aspects of the changes they brought.

Sofía worked in the Sandinista underground for two years or so prior to the overthrow of the dictatorship, running messages for the Front and establishing contacts with the foreign journalists based in Managua (her fluent English came in handy). But her brother, Franklin Montenegro, followed instead in the footsteps of their father, who had been a senior officer in Anastasio Somoza's hated National Guard. Franklin rose through the ranks of the Guard and ended up commanding Somoza's forces on one of the key battlefronts during the urban insurrections of 1978-79. When the "somocista" forces collapsed, Franklin tried to flee with other Guard units across the Gulf of Fonseca to El Salvador, but was captured by a Sandinista patrol and imprisoned. Then he was shot and killed "while trying to escape" - Sofía believes he deliberately courted suicide to spare the family the public revelations of the atrocities he and his National Guardsmen had inflicted on the population. But because Sofía was prominent within the Sandinista movement, and refused to appeal to the Front leadership to release her brother, her mother blamed her for Franklin's death - leading to a traumatic estrangement through most of the revolutionary decade of the 1980s.

During that time, Sofía became one of the founding staffers of Barricada, and served as foreign editor before (in 1989) founding a fascinating supplement called Gente (People). Gente became the most popular feature of the paper and broke a lot of new ground with its discussions of gender issues, sexuality, and other themes. She was, of course, among the 80 percent or so of editorial staff who left Barricada when the "orthodox" wing of the newspaper took over in 1994. (This is the "coup" referred to in the title of my book manuscript on Barricada, Chronicle of A Coup Foretold.) Since that time, she's been working at a communications-research centre established by Barricada's former director, and Sofía's former lover, Carlos Fernando Chamorro; she's just published a book about women and communications in Nicaragua, which she presented to me last night, pointing out that my Master's thesis on Barricada makes an appearance in the bibliography. At last, I'm famous! According to Sofía, whenever somebody asks her for the details of what happened at Barricada in the 1980s and early '90s, she just gives them my thesis to photocopy - she says she herself has forgotten most of the details, and is glad to have my work nearby to remind her!

Our conversation last night ranged far and wide, and included some juicy gossip about a phone call she received earlier this year from one of the Barricada editorial board, asking her (along with several of the other old staff) to come back to work on a new version of the newspaper. Apparently the Front's leaders came to realize the error of their ways in deposing the crew who'd turned Barricada into an interesting and semi-independent paper in the early '90s, and replacing them with half-skilled propagandists. Naturally, Sofía (and apparently everyone else from the old team who was contacted) told them to take a hike (Sofía put it slightly more bluntly, as is her wont!). But she did offer the prediction that Carlos Fernando Chamorro would try to found a new daily paper once he finishes his studies at Berkeley next year - so perhaps there'll be another chapter to write in the story of revolutionary journalism somewhere down the line.

We also spoke a fair bit about the story of Zoilamerica, Daniel Ortega's stepdaughter who went public in March with allegations that he'd sexually abused her from the age of 11. It turns out - I should have guessed - that Sofía had been instrumental in marshalling support for Zoilamerica when she first told her tale. Needless to say, she believes the allegations completely, having spent many hours working through the gory details with Zoilamerica herself. She also recommended to me a book that's just appeared and which I picked up this morning, called The Silence of the Patriarch (a takeoff on Gabriel García Marquez's Autumn of the Patriarch, just as my own manuscript on Barricada draws its title from Marquez's Chronicle of a Death Foretold). It's a collection of materials on the Zoilamerica case edited by Juan Ramón Huerta - another guy I'm trying to track down for an interview while I'm here. He was one of the very few editorial staff at Barricada who stayed on after (and, indeed, welcomed) the coup against Chamorro and the others in 1994. Eventually he became chief editor of the paper before it died ... but he seems to have changed his tune quite considerably since that time, to the tune of editing this compilation that's highly critical of Ortega's personality and behaviour. Anyway, Sofía's strong conviction that Zoilamerica is telling the truth I found pretty persuasive in and of itself. She also cited the alleged events as the reason that Daniel's partner, Rosario Murillo (who's interviewed and profiled in the <nica2.htm> Website file I mentioned earlier), has managed to accumulate so much "power behind the throne." It's rather sickening to contemplate, but her argument is that Rosario got Daniel under her thumb by knowing all about the abuse of Zoilamerica, and telling nothing - in effect, pimping her daughter to her husband. If that's true, it really beggars belief.

We also spoke about Sofía's feelings of guilt at having outlived some of her close Sandinista comrades. This is a movement that has suffered the loss of some of its most creative and vibrant talents at a preposterously early age. Sofía's great friend, the cartoonist and satirist Roger Sanchez, died in 1991 of stomach cancer at age 30; another close friend from Barricada, Noel Irías (whom I interviewed in 1991), also died of cancer in his early 30s. For Sofía, these bizarre illnesses were related to the shock of the Sandinistas' loss of power in 1990 - she sees them as somehow psychologically induced. They weigh very heavily on her, along with the death of her brother: she's someone who carries around a lot of ghosts. Perhaps this explains why, at the end of the evening, we found ourselves sitting around her dinner-table with the wreckage of a pizza she'd ordered nearby, knocking back the last of the rum, and with Sofía doing a tarot-card reading for me - the first in my life, I hasten to add! I wish I could remember exactly what the prognostications were. Apparently I will be presented with a major choice in the next few months, one that I need to be skeptical and think very carefully about. Sorry, but the rest is a bit of a blur. It was late, and the rum was rather good.

I have to say, incidentally, that this was probably the evening when I decided I've really, truly quit smoking (tobacco, that is). Sofía puffs like a chimney, and if I was ever going to cave in, it would be in her company, with the drinks and conversation flowing freely, and Sofía lighting up a new Belmont every five minutes or so. But I managed to grit my teeth and get through with only a few deep, nostalgic whiffs of second-hand smoke for consolation.

I stumbled out of Sofía's place around midnight, but not before I'd vowed to take on a project that seems to make good sense: to launch Sofía properly into cyberspace. She frankly avows that she's a "techno-brute" who's barely got a handle on e-mail; so I'm going to put time this fall into assembling a Web page for her, incorporating the extensive interviews about her life and views that we did in 1991, along with some of her favourite (and most recent) journalistic writings. Look for it to be up-and-running by Christmas! It would be a pleasure to help publicize her work. She's really one of the people in the world that I feel a bond with; she's taught me an amazing amount about this country and its revolution; and I know that most of the people who've encountered her through the interview material have learned a lot - sometimes about themselves.

After a rather sl-o-o-o-w start to the day today, I managed to get my act together sufficiently to meet Daniel Alegría for lunch. He's the eternally boyish former editor of the Barricada's international edition who's now working at Oxfam. In marked contrast to Sofía, Daniel is a total technophile, who basically put together Oxfam's computer network here in Nicaragua ... and so, much of our conversation revolved around the wonders of the 'Net and the Web, though we also found time to range across Nicaraguan politics and other subjects. He's someone whose good cheer is always infectious, and after lunch we headed back to the OXFAM office, where I was able to check my e-mail (though I didn't have time to answer any of it properly - sorry, all). After that, I wandered home to sleep for most of the rest of the afternoon ... and now it's time to sit down to some of the serious manuscript-and-dissertation editing that I've been studiously avoiding for the last couple of days. Talk to you soon!

There remains, then, only a couple of days of writing to finalize the Barricada manuscript once I'm back in Canada; then I can send it off to my prospective publisher. A further challenge will come when I try to slash the book down to about a third or two-fifths of its present length for dissertation purposes. But I really feel the results of these two weeks in Managua have vindicated the decision to come back here for one last visit (at least as far as the Barricada work is concerned). There's just oodles of stuff you could never get your hands on in a North American library or over the Internet, and I have the satisfaction now of knowing I've given this (admittedly obscure!) case-study as close an analysis as it will probably ever receive, in English or in Spanish. At least, it's hard to imagine anybody ever bothering to spend as much time interviewing the principal actors as I've done over the last few years - and even if somebody decides to do it in the future, it's likely the memory of the participants will have faded on the details! I will probably be posting the text of my manuscript on my Web site when I'm home in the fall, although unannounced and without links - so that interested individuals can access it by contacting me separately, but also so I can avoid jeopardizing my chances of publishing it in print. So if any of you would like to get the "full scoop" on this interesting tale, let me know in the autumn, and I'll forward the "hidden" Website address.

Now it's time to pack up my gear once again, hop on a plane tomorrow morning - hopefully LACSA will be a tad more efficient this time. Another night bus back to Guadalajara will give me a chance finally to send this massive missive off to you by e-mail. Then, first thing Sunday morning - Havana, and a chance to kick back for several weeks, explore, and enjoy myself without this research monster lurking about. As mentioned, I'll be incommunicado the entire time I'm in Castroland, but I'll be trying to put together some kind of "Cuba Diary" to share with you once I'm back in Vancouver. I've decided to take my laptop computer along for the ride, despite the risk of theft - it just makes life so much easier than with paper-and-ballpoint.

The thought of returning home on September 2nd fills me with the pleasure you can feel only when you haven't figured out a way to take those nearest and dearest to you along on your far-flung adventures! I'm looking forward to sitting down and chatting with all of you who'll be within striking distance geographically in September. Meanwhile, thanks to those who've continued to send e-mail over the course of the summer - please be assured that every word has been avidly read and appreciated.

And so, with the sweat dripping down my forehead and onto my keyboard, it's time to take a nice cold shower (no other kind in this part of the world, I'm afraid), and head out for my last Managua meal and bottle(s) of Victoria. There should be time to knock out a quick paragraph or two back in Guadalajara before I consign this message to cyberspace, so stay tuned, and meanwhile accept all my love from the distant but still rather special land of Nicaragua.

I'm looking forward to my three days of decadent luxury (by my standards) at the Hotel Capri in Havana, and then a trip into the unknown - although thanks to my friend and former student, Paul, I have a contact in Havana who should be able to find me a home-stay for the rest of my time in the capital. Thereafter, we'll just have to take it day by day - but that's life, right? However much I'm eagerly anticipating these new adventures, it's hard to imagine being out of touch with friends and family for four weeks: Internet access is tightly-controlled by the Cuban government, so the "Cyber Cafe Video Beer" hasn't opened a Havana branch yet! But you can look forward (with dread, if you prefer) to that "Cuba Diary," which I'll enjoy putting together for you and will e-mail once I'm back in Guadalajara on August 30th. Until then, you'll be in my thoughts.

Love,

Created by Adam Jones, 1998. No copyright claimed for non-commercial

use if source is acknowledged and notified.

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

Last updated: 10 October 2000.