Franz Kafka went to places no other writer had, and left an indelible mark on twentieth-century writing. "Kafkaesque" has joined "Orwellian" in our political lexicon. I came to him through The Trial in an undergraduate English course. What made the sometimes-crushing bleakness of his work bearable was its leavening with a comic tone and an irrepressible absurdist outlook. In that sense, Samuel Beckett and Eugene Ionesco owe him a great debt. So do the magical realists of Latin America - García Márquez and the others - with their hallucinatory vision of politics and society.

Popular culture has also been penetrated by Kafka's gaze. I hear it in Bob Dylan's "Desolation Row," or Dire Straits' hilarious "Industrial Disease." Most of all, perhaps, Kafka hovers over cinema. Wherever someone is tormented by irrational forces, as in After Hours, Blue Velvet, or Jacob's Ladder; or where characters are drawn into bizarre labyrinthine confrontations with administrative or criminal authority, as in Die Hard and The Fugitive - the Kafkaesque is not far away.

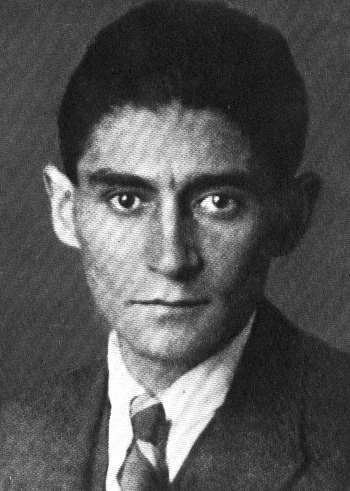

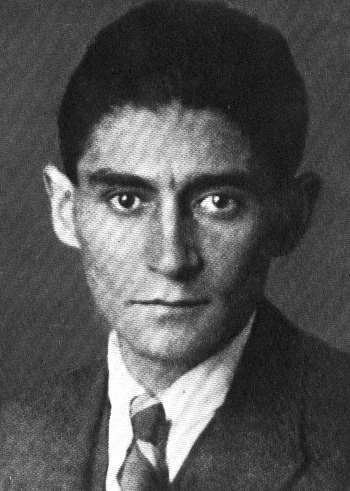

In Summer 1989, only a few months before the Berlin Wall fell and the Czechoslovak regime along with it, I visited Prague. It was a time of suppressed ferment. In neighbouring Poland, Solidarity was already being elected to the national parliament. In Czechoslovakia, the cultural pall of state socialism was still much in evidence. Kafka served as a good thermometer for the political climate. New Czech editions of his work were being prepared and published, and his brooding features adorned many sidings: a theatre troupe was publicizing a production of The Trial. (Link to my letter to the editor describing Kafka's Prague.) I visited the tiny house, which seems as though it could not have been inhabited by anyone larger than elves, where Kafka wrote The Castle - a short walking distance from its inspiration, Prague Castle. The residence had been turned into an ordinary book-and-souvenir shop, not a Kafka tribute per se. The only acknowledgment of its previous tenant was a dignified plaque, with "Here Lived Franz Kafka" in Czech. Doubtless the little house has now glammed itself up for post-communist times.

Albert Camus wrote of Kafka: "I shall speak like him and say that his work is probably not absurd. But that should not deter us from seeing its nobility and universality. They come from the fact that he managed to represent so fully the everyday passage from hope to grief and from desperate wisdom to intentional blindness. His work is universal (a really absurd work is not universal) to the extent to which it represents the emotionally moving face of man fleeing humanity, deriving from his contradictions reasons for believing, reasons for hoping from his fecund despairs, and calling life his terrifying apprenticeship in death."

[Suggested reading: The Nightmare of Reason: A Life of Franz Kafka, by Ernst Pawel (New York: Farrar-Straus-Giroux).

Created by Adam Jones, 1998. No copyright claimed for non-commercial use if source

is acknowledged and notified.

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

Blog: http://jonestream.blogspot.com

Last updated: 10 October 2000.