Excerpted from The Press in Transition: A Comparative Study of Nicaragua,

South Africa, Jordan, and Russiaby Adam Jones

Hamburg: Deutsches Übersee-Institut, 2002

[Link to order The Press in Transition from the Deutsches Übersee-Institut.]

Note: All quotations that appear without a footnote are drawn from the body of interview materials compiled for The Press in Transition. A complete list of interviews, dates, and locations appears at the end of the book.

For centuries, the press and politics have been intimately intertwined. Indeed, the freedom of print media, and later of their broadcast and new-media counterparts, has been seen as definitional to the wider freedoms of expression and association that define liberal democracy. From Milton's Areopagitica and the First Amendment, through to Mill and Orwell,(1) the notion that truth is knowable, but that it can only emerge if individuals are free to disseminate it, has guided the assumptions of many of the world's greatest liberal thinkers. A recent contribution to the study of mass media and political transition makes the point at some length, but with admirable concision:

There is a common understanding [in liberal-democratic societies] that a strong connection exists between mass communication and democracy. Simply put, the assumption is that for democracies to function, civil society requires access to information as a means to make informed political choices. Similarly, politicians require the media as a way in which they can take stock of the public mood, present their views, and interact with society. The media are thus viewed as a vital conduit of relations between state and society. But the media are not simply instruments of political actors, lacking their own independent power. Democracies are political systems that allow for the dispersal of power and public access to it, but liberal-democratic theory also notes that such systems can be easily corrupted, thereby undermining participation and voice. Institutional checks and balances within the state structure are highlighted as necessary firewalls against such abuse, and the media are equally valued in this area. As the fourth estate or watchdog of government, the media are expected to critically assess state action and provide such information to the public. Ideally, then, the media not only provide a link between rulers and the ruled, but also impart information that can constrain the centralization of power and the obfuscation of illicit or unethical state action.(2)

Those who reject liberal prescriptions have, nonetheless, acknowledged the centrality of the press and other media to political strategy. A noted journalist named Karl Marx moved, over the course of his political life, from a classical-liberal view of the press as "the omnipresent open eye of the spirit of the people" to a more radical, social-revolutionary conception: the press's role was "to undermine all the foundations of the existing political system." But the inseparability of journalism from his political project was plain at each stage.

Vladimir Lenin developed Marx's mobilizing model further, seizing upon "an all-Russian newspaper" as the only "means of nurturing strong political organizations ... [of] generaliz[ing] all and sundry sparks of ferment and active struggle."(3) In the post-World War II era, a mobilizing model of the media was a key ingredient of the "developmentalist" prescriptions advanced by scholars like Lucien Pye, Gabriel Almond, and James Coleman.(4) Underdevelopmentalist critiques rejected this communications model along with the western conceptions of "modernization" that underpinned it. They called instead for a "New World Information Order" (NWIO) to redress imbalances in the international political economy of news production and dissemination.(5)

Given its importance to these various "democratic" and "authoritarian" political models,(6) it is striking that the press receives such little attention in the burgeoning literature on democratization and political transition. "The role of mass communication" in democracies and democratizing societies "is not open to question," according to Patrick O'Neil; but "despite the fact that the recent spread of democracy has led to a commensurate amount of scholarly work on authoritarian collapse and democratization, little attention has been given to the media in this regard." The press has indeed been "absent from relevant discussions"; it is "the forgotten actor in transition analysis," according to Lise Garon (1995).(7) The first landmark study of transition, O'Donnell, Schmitter, and Whitehead's four-volume Transitions from Authoritarian Rule (1986) completely ignored the media, except as a peripheral subset of the "revival of civil society." Larry Diamond and Juan Linz at least acknowledged the deficit in their edited work (1990), the most ambitiously synoptic project of its kind to date. They noted that "we lack, in the social sciences, a good understanding of how a democratic press develops over time and articulates with other social and political institutions." But they themselves offered nothing to fill the void.(8)

In the years after Diamond and Linz's compendium appeared, a number of important case-studies were published. They include Lise Garon's chapter on the Algerian press, Elena Androunas's and John Murray's overviews of post-Soviet media transformations, Peter Gross's detailed treatment of post-Ceauescu Romanian media, and the monographs on East Asian cases by Chan and Lee (Hong Kong) and Daniel Berman (Taiwan).(9) But a void stall yawned, at least in the eyes of the first theorist to adopt a comparative approach to media and political transition. In his book Internationalizing Media Theory (1996), John Downing wrote scathingly of a kind of "structuring absence" in political-science analyses of key political phenomena, including "questions of ... regime transition." These, he argued, had "generally been researched without benefit of attention to communication processes, rather as though politics consisted of mute pieces on a chessboard." In his more specific treatment of the transition literature, Downing was scarcely less critical. "Know-nothingism" prevailed "among political scientists about the very communication processes by which authoritarian rule, regime transition and contestatory political movements develop or decline." Journalistic treatments had been at least a match for more traditional "scholarly" investigations of transitional media.(10) Downing instead advances a proposition that the present work shares, asserting

that mainstream media are a pivotal dimension of the struggle for power that is muted but present in dictatorial regimes, [and] that then develops between political movements and the state in the process of transition from dictatorship (though perhaps only into some form of "delegative" democracy). This equally applies in the consolidation period after the transition.(11)

Downing in fact moves well beyond mainstream media in his analysis, drawing in "such forms of expression as graffiti, theatre, music, [and] religious observances" into the discussion. His original and provocative description of "marginal" communications processes, and their sometimes dramatic influence on transition processes, represents both a summing-up of sociological and journalistic work on the subject over the last twenty years, and a paving of the road for future comparative investigation. The ambit of my own comparative project is narrower thematically -- I do not move much beyond mainstream print media -- but it does follow Downing's "marginal" pursuits in arguing for greater attention to tabloid-style "yellow" media like Nicaragua's El Nuevo Diario, Jordan's Shihan, and Speed-Info in Russia, or "qualoids" such as Moskovsky Komsomolets, as political and professional actors in their own right.(12) I think it is also fair to say it investigates their agendas and impact in a more detailed and multinational manner than Downing manages in his analysis, which is bounded by the relatively well-studied Russian, Polish, and Hungarian cases.

The first truly global surveys of media and transition appeared in 1998: Patrick O'Neil's edited volume, Communicating Democracy, and Democratization and the Media, edited by Vicky Randall.(13) O'Neil's work adopts a cross-regional case-study approach, as does my own. Ten chapters in two hundred pages, however, does not leave much room to move beyond system-level analyses, usually written by those (Elizabeth Fox on Latin America, Owen Johnson on Central Europe) whose more substantial contributions have been available for years. Despite many thought-provoking moments, O'Neil's introduction does not depart from, or significantly supplement, a classic liberal analysis. As for the individual contributions, their quality varies, as with most edited volume of this type. Johnson's survey of "The Media and Democracy in Eastern Europe" is actually a small masterpiece of concision and useful insights, well-sprinkled with case-study examples despite its brevity. Silvio Waisbord on "The Unfinished Project of Media Democratization in Argentina" adds a well-conceived case-study to the (English-language) scholarship on transitional media. At the other end of the scale, Louise Bourgault's analysis of "The Politics of Confusion" in Nigeria seems to have strolled into the wrong volume: the media finally make their first appearance thirteen pages into a nineteen-page chapter.

The contributions to Randall's edited volume also tend to stay stuck at the system level, while offering useful and insightful overviews of media and democratization in Taiwan, China, Poland, the Middle East, and Mali, as well as industrialized liberal-democratic countries (the United States, France, and Britain). Much the same can be said of the most recent and bulky contribution to this burgeoning sub-field: Democracy and the Media, edited by Richard Gunther and Anthony Mughan.(14) This nearly-500-page tome in one sense stands as the most ambitious survey of trends and transformation in democratic media; but it limits itself to the developed West and the post-Soviet societies of Eastern Europe, without any serious attempt to expand its range to the Third World. Thus, despite these promising recent additions to the literature, The Press in Transition can still make a claim for distinctiveness: not only does it draw its case-studies from four continents and diverse media systems, but it seeks to bridge system-level analysis with up-close consideration of transformations and continuities at the institutional and even the individual level.

In its concluding chapter, this book seeks to sketch an analytical framework of the press in transition, to suggest how such a transition can be conceptualized and differentiated from "ordinary" transformations in fast-moving mass media, and to draw out some detailed similarities and differences in the way the press has negotiated tumultuous political transitions worldwide. A worthwhile prelude, in my view, is to arrive at some understanding of how the press functions the world over. I stress here, and will repeat in the conclusion, that the emphasis in this work is on the written press. I believe that many of the basic frameworks and interpretations are valid for broadcast media (and occasionally new and alternative media); but their applications should be viewed throughout as more tentative in these spheres. What are the basic imperatives that unite both capitalist and state-socialist press systems? What do the sponsors of press organs expect from "their" media; how do journalists and editors charged with the task of generating editorial content seek to do so? What tensions and clashes may result from the interaction of sponsors and professional journalists?

Usually, the situation is that a newspaper follows the point of view of its owner, more or less -- in the west and everywhere else.

- Alexander Sychev, foreign editor, Izvestia

The mobilizing imperative that dominates a given press system or newspaper institution, and the identity of the sponsor and primary mobilizer, is easily enough isolated by asking a few basic questions. Who owns the institution? Who pays the staff, and covers the cost of inputs? If it is not the state or regime directly, what is the relationship between the sponsor and the state or regime? If we expand the analysis beyond simple survival, the broader mobilizing imperative can likewise readily be ascertained. What constituency does the newspaper target? What is the stated agenda of the institution, as this is expressed in editorial page "leaders"? (Where, in other words, do "leaders" lead, and whom do they seek to lead?) Which taboo areas are respected -- that is to say, what social, economic, and political options tend to be foreclosed, rendered "unthinkable," in the paper's reportage and editorial commentary? What, at its heart, qualifies as "news"? Which social sectors and class interests tend to be selected out for special attention, treated more favourably and attentively, as measured (for example) by the kind of supplements the paper publishes? Given the limitations of the social sciences, it is best to consider all these questions in tandem. Any of them alone, however, may serve as a fairly reliable lead to the source and character of the wider mobilizing imperative, in both its material and editorial manifestations.

The guardians of the mobilizing imperative seem best located, across media systems, in the nexus of owners, managers, and senior editors. These together control the "strategic heights" of any newspaper's operations. They are largely responsible for day-to-day strategizing at both material and editorial levels. They act to balance the varied, sometimes conflicting, mobilizing considerations -- beyond the simple imperative of institutional survival -- against an analytically-separable set of professional imperatives, discussed in greater detail below. As a result of the "gatekeeping" procedures that obtain in newspapers as in all institutions and organizations, the sponsors of the mobilizing imperative tend to display -- and demand -- a high degree of common purpose and ideological cohesion. Any institution, though, has its fissures. It appears that the bond between owners and managers is stronger than that between managers and editors, with correspondingly higher levels of conflict evident in the latter relationship. The relationship between owners and editors is more variable and contingent still. The South African case studied for this book exemplifies well the complexities of these relationships. In the modern history of the English-language press, an "English model" of editorial autonomy and intra-institutional communication prevailed. Its essential feature was the establishing of direct lines of communication between editors and owners, to give editors a degree of breathing space from management's day-to-day mobilizing priorities. At the same time, though, ownership was highly dispersed through shareholders (in stark contrast with centralized state or party ownership in classically authoritarian societies). The role of the owner was thus more "hands-off" than in the state-socialist societies or, for that matter, the more personalist operations of the early Hearst or modern Black eras.

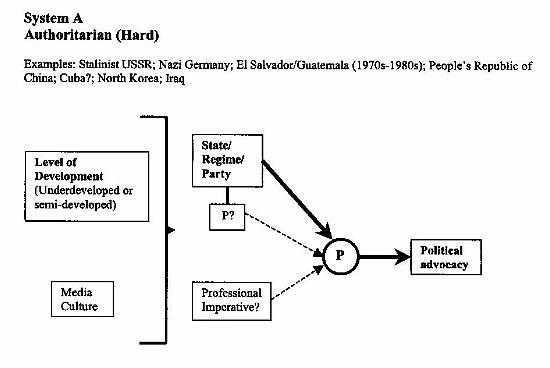

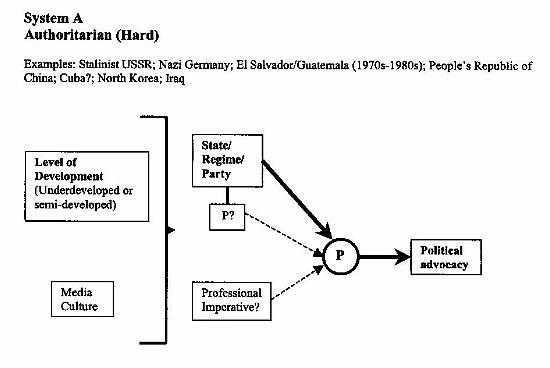

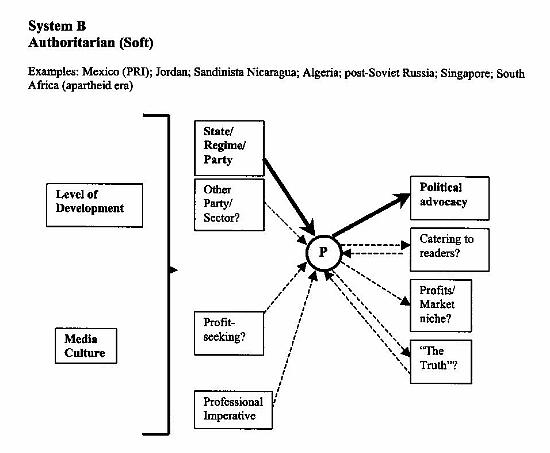

Environmental variables act to condition the mobilizing imperative prevailing in a given media system or institution. The most important are 1) the degree of underdevelopment and 2) the degree of regime authoritarianism -- with a strong correlation evident between the variables as well. Material concerns are so primary in press functioning, and underdevelopment exacerbates them to such an extent, that we need to consider the ways in which this "meta-environmental" variable makes itself felt.

Underdevelopment correlates with poverty and illiteracy, which in turn act to constrain the reach of the written press. Hall writes of the Malawian press that it "is operating in a market in which a majority of people cannot read, cannot afford to spend money on newspapers, radio receivers or batteries, and are difficult to reach because they live in rural areas."(15) In rural areas of northern Nicaragua, according to a foreign aid worker with whom I spoke in 1991, newspapers were usually purchased in bulk (at a steep discount) days or weeks after they were published. They were bought not mainly for informational purposes, but for use as toilet paper -- though the aid worker assured me that literate peasants read them first.

Underdevelopment also privileges broadcast over printed media. When illiteracy and poor transportation infrastructures are combined with questions of cost-efficiency, the advantage of broadcast over print media is heightened, at least as far as mass constituencies are concerned. Print media -- at least "serious," mainstream media -- are targeted disproportionately at intellectuals and professional elites. In countries where these classes speak a foreign tongue, moreover, media may be limited to audiences with linguistic capacities that the overwhelming majority of the population does not share. In all of Africa, according to Kwame Karikari, "Only Tanzania had a[n African-language] daily and weekly, and Kenya a monthly, all in KiSwahili, each of which had [a] 100,000 circulation figure. Very few others surpassed 50,000 copies per edition ..."(16)

Distribution difficulties. The written press, unlike its broadcast counterparts, relies upon a distribution infrastructure that is especially sensitive to the constraints of underdevelopment. Carlos Fernando Chamorro vividly described the constraints that underdevelopment imposed on his former paper, Barricada -- even in a capital city that was home to a third of the country's population:

It's a problem of circulation. Let's say there are in Managua 150 or 200 agents. Each agent has under him a group of kids -- most of them are kids. They study. Now, a good seller could sell 80 newspapers, maybe up to a hundred. But what happens is that you have the same agent taking both El Nuevo Diario and Barricada. So that kid who could sell 80 or 100 papers would only sell 40 of Barricada. If, on the same day, he has also to sell [the pro-Sandinista weeklies] El Semanario or La Semana Cómica, that adds to the amount of paper he has to carry. The result of all this is that if you get the papers to the drop-off point a bit late, the kids will take El Nuevo Diario and not come back [for Barricada]. The amount of time they can devote to selling the papers is relatively brief, because they have to go on to study [later in the day].(17)

Dependence on imported material inputs. Karikari writes that African societies provide only a "weak industrial base for a dynamic mass media": "Not even paper stapling pins are manufactured in Africa: paper, ink -- indeed, all the material inputs for publishing -- have to be imported. Thus, in countries where currencies are constantly being devalued, the unit price of newspapers, magazines and books gets ever higher and, finally, unaffordable."(18)

Paucity of advertising revenue. Hall writes of Malawi, a paradigmatic Third World example, that

The nature of [the country's] limits the opportunities for media to earn revenue from advertising. The rural/agricultural sector, which is dominant, does not generate much advertising. there is a small internal market for manufactured goods and the structure of business in many sectors is monopolistic, which means manufacturers don't have to advertise as much as in a more competitive environment because they have already developed large market shares. ... All this forms a vicious circle. Because the advertising base is low, publishers need to earn more from copy sales[,] which means they need to place a high cover price on their newspapers. Because incomes are low, fewer people can afford to buy them[,] which means lower circulation[,] which means less appeal to advertisers. It also means, obviously, that the cost of publishing is met by the newspaper buyer, rather than the advertiser.(19)

Underdevelopment and authoritarianism. In underdeveloped societies that also exhibit authoritarian patterns of governance -- the large majority -- mass media tend to depend overwhelmingly on the state or ruling regime. "What is important for the authoritarian conception is its instrumental approach," said Yassan Zassoursky, dean of the journalism faculty at Moscow State University. "Media are seen as a tool. The tool might be an axe, it might be a whip, it might be a carrot; but it's an instrument. And an instrument in the hands of the mighty -- the rulers, mostly." Even opposition media voices, if permitted to exist, will regularly depend on the goodwill or at least benign indifference of rulers. In these resource-scarce societies, the state/regime often exercises a monopoly on materials and services that are vital to media functioning. In a positive sense, it will be able to channel a wide range of inducements and subsidies to favoured media institutions -- those it does not own outright (or control indirectly, as in Jordan). The catalogue of state "carrots" on offer to the Mexican press under the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), for example, could be extended with few alterations to numerous societies in the developing world: "subsidized newsprint, state control of newsstand distribution, circulations inflated by government purchasing and advertising revenues dependent on government advertising, and a revolving-door relationship between newspaper editors and government press offices."(20) Through judicious manipulation of these assets, a more sophisticated authoritarian state can maintain its sway at discreet arm's length, even over "independent" and oppositionist newspapers. "When a subsidy makes up a certain part of your income, and a rather important part, you don't even have to be pressured into acting," said Alexei Pankin of the Media Development Program in Moscow. "You just know that if you want to keep it, you have to stick within certain boundaries which basically exist in your head."

Nor does this exhaust the list of positive inducements that the authoritarian state can brandish. It can "encourage" private business to establish or otherwise help sponsor media projects.(21) It can provide direct payoffs to editors and journalists, right down to "supplementary" pay envelopes slipped into the pocket of the reporter on the beat. In underdeveloped societies, these are often mainstays of a journalist's or editor's income; plum patrimonial relationships may be highly prized and hotly competed for. The stuff and substance of the reporter's daily life -- sources and access to information -- can be granted disproportionately to the sycophant: the regime is, after all, the story that often must be reported on, even by more "objective" news standards. It is in any case usually the custodian of the archives, and the security guard at the press conferences.

In the most highly-centralized and repressive political systems, the state's reach is all-pervasive, touching on many more facets of a journalist's life than the ability to earn a living wage:

Like other workers in a centralized system that allocates most jobs regardless of individual preference, [Chinese] journalists know they must work where they are assigned in order to eat. If they give up their jobs, they must also surrender their work unit's housing, food coupons, and other subsidies. Refusing to work on the basis of principle is more than a luxury; in China's work unit system, it can be suicidal.(22)

Even in the comparatively liberal media climate of Jordan, according to Jordan Times political editor P.V. Vivekanand,

very few [people] have been willing to openly challenge the system. And those that did got in trouble. They were made miserable; their passports were withdrawn; they couldn't travel; they could be questioned for hours and hours, with nothing coming from the questioning -- sheer harassment. After a time, you say, "What the hell am I working for? If I have to go and report to someone [in the security apparatus] at nine o'clock every morning, and be there until two o'clock, then be asked to come back the next morning ..." You start to think, "Is this the price I'm paying for trying to do an objective, truthful job and live up to the principles of my profession?" Not many people can withstand that test.

For those who conform, there are important rewards. The material pressures media institutions often face in politically and economically freer environments may be rendered redundant. As we will see in Chapter 4, Vivekanand's Jordan Times made no profit for nineteen years, surviving thanks to indirect regime sponsorship. The Citizen in South Africa performed at below-survival levels for years, thanks to the (sufficiently) generous expenditures of its Perskor parent (Chapter 3). And the negative inducements available to the regime are numerous. They range from the aggravating to the appalling. Media can be hemmed in by an apparatus of direct censorship, or (more commonly) by indirect censorship exercised through the selective application of media or libel legislation and intricate licensing restrictions. The material functioning of the media is also exposed at many points to the disciplinary actions of a powerful state or regime. Louise Bourgault's depiction of Nigerian media under military rule provides a veritable catalogue of regime "sticks":

Nigeria's press has suffered such indignities as the temporary seizure, banning, and closure of newspapers; harassment of vendors, distributors, and even readers; the hijacking, impounding, and arson of newspaper delivery vans; a shortage of newsprint; and even the firebombing of presses. Bogus editions of the feistier publications -- the News and the Sunday Magazine -- have even been circulated [!]. Meanwhile, the country's journalists and publishers have suffered harassment, intimidation (of themselves, their spouses, and their children), detention, arrest without trial, death sentences, and even death by parcel bomb.(23)

In Cuba, similarly, "a nascent independent press" must grapple with the difficulties of procuring "basic supplies, such as pens, notebooks, [and] typewriters" outside state distribution channels. It must also reckon with the regime's restrictions on ownership of fax machines and computers.(24) The state can pressure businesses, whether state-owned or private, to withhold advertising from oppositionist media. In Dakar, the newspaper Sud Hebdo received just such a cold shoulder, according to its chief editor, Mamadou Oumar Ndiaye:

No business, no corporation, no state-owned company would buy ads in the paper. Why? Most of the people who run state institutions, or even private businesses, are afraid to appear to be supporters of ill-thinking people. The nature of the state in Africa is such that, whatever situation you are in, you still have some sort of links, and you are to some extent dependent on the state. So that you constantly fear retaliation. Even foreign business organisations have the same attitude. Because, in Africa, the state is the largest single contractor.(25)

Under regimes better termed tyrannical than authoritarian, total conformity is enforced in cruder fashion. The trussed and tortured bodies of journalists and editors along Salvadorean and Guatemalan roadsides in the 1980s attested to the willingness of state agents to punish deviation with death. In other, superficially less authoritarian societies -- Mexico, Colombia, Algeria -- bloodshed is a greater or lesser feature of the journalistic landscape. "Non-regime" actors including gangsters and religious fundamentalists are as likely to be the ones delivering the death-threats or planting the car-bombs. Often, of course, the regime will turn a blind eye to such activities, or collude with them outright, in addition to launching its own crackdowns.

The standard effect of these positive and negative inducements under authoritarianism is for the media -- especially broadcast media -- to be owned and administered outright, and used to mobilize public support for regime leaders and policies; or, in "softer" authoritarian societies, for media to maintain a superficially autonomous but generally sympathetic orientation towards those leaders and policies. ("This is a government television station," said one emblematic TV executive, "and we believe that the news should be consistent with the government's point of view and its national policy."(26)) What is truly remarkable is that the trend is not universal. There are numerous examples of media workers seeking to operate outside authoritarian constraints. Often this requires courage on a scale that can only leave the analyst slack-jawed, and that tends, lamentably, to correlate with a shorter lifespan. Under hard authoritarianism, a newspaper(27) may manage to establish other sources of sponsorship that help it confront the basic challenge of material survival. The most common are wealthy patrons (as the Chamorro clan in Nicaragua supported La Prensa through the Somoza dictatorship); opposition parties, trade unions, or other political groupings; and "civil society" -- an elite or mass readership that can support the enterprise through newsstand sales and associated advertising revenue.

But the harder and/or more underdeveloped the authoritarianism, the rarer are such instances of semi-autonomy and independence. At the extreme, the trend is for media subservience to the regime's mobilizing agenda to be virtually total. Indeed, it makes little sense to differentiate between press and regime under such circumstances. In Iraq, "the press is the state," according to one dissident journalist; as another in neighbouring Syria put it, "the press is a branch of government and journalists are government employees."(28) Senior editors are likely to be handpicked party appointees and cronies;(29) they may serve in separate capacities as political leaders and decision-makers. As for journalists, there is little practical difference between their daily task and that of the professional mourners hired to emote at Chinese funerals. What Alec Nove has called "the language of catechism" dominates editorial content.(30) The Stalinist media model described by Nove (and satirized by Orwell) is the classic example. Though for the most part it has been consigned to the ash-heap of history, it still survives in isolated outposts, and retains its capacity to amuse, if not inform or edify. Consider this news roundup offered by the (North) Korean Central News Agency, on a day in February 1997 when the defection of North Korean professor Hwang Jang Yop was dominating headlines worldwide:

Conveyed in papers is news that Kim Jong-Il's Selected Works (vols. 9, 10 and 11) were brought out by the Workers' Party of Korea Publishing House and commemorative stamps and postcards [were] issued by the Ministry of Post and Telecommunications. ... It is reported in the press that senior party and government officials appreciated the sixth part of Kapf Writers, part 30 of the multi-part feature film The Nation and Destiny. Conspicuous in the press is the February Appeal issued by the Central Committee of the National Democratic Front of South Korea calling upon the South Korean people from all walks of life to brilliantly adorn the 55th birthday of the great General Kim Jong-Il as the anniversary of victory which will long shine in the annals of the nation. Rodong Sinmun [newspaper] reports that the South Korean puppets ceaselessly staged war exercises and committed provocations near the military demarcation line ...(31)

And so on, with news of the defection conspicuously absent. Even in a softer autocracy like Jordan, press adoration of senior regime figures may know few bounds:

Your Royal message delighted our hearts which are brimming with love and allegiance to Your Majesty as it reflected Your Majesty's support for the Jordanian journalists who have been relentlessly working under your Hashemite standards and contained pure wisdom and Royal directives for pursuing efforts to follow the sound course in helping the country to achieve its objectives. ... We solemnly pledge to remain true to the cause under your directives working relentlessly and unyieldingly so that Al-Ra'i can remain a platform for free and responsible expression.(32)

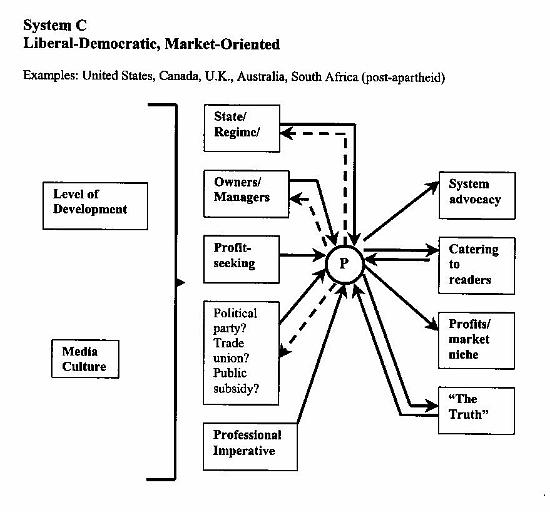

So declared the chairman of the board of Al-Ra'i, the Hashemite kingdom's leading establishment daily, in response to King Hussein's fraternal message of congratulation upon the paper's 25th anniversary. It is easy to poke fun at such examples from a western, liberal-democratic perspective. One advantage of an overarching mobilizing framework, however, is that it can be readily extended to western media themselves. What we have described is the mobilizing imperative as it tends to operate under authoritarian, especially underdeveloped, societies: forcing or luring most media into the more or less formal embrace of the state, in return for which media institutions receive the requisites of survival and a range of other useful "carrots." The "free" media institutions of the western world may be less prone to direct regime intervention and the shackles of underdevelopment alike. In a free-market environment, though, in which they operate for the most part as mainstream corporate enterprises, they are free to fail commercially. Their overriding mobilizing imperative, externally generated by sponsors and shareholders, is profit. Under market conditions, corporations called newspapers have as their primary source of income (hence profit) other corporations -- those that advertise in the newspaper's pages. Large press institutions in these circumstances are seamlessly woven into the fabric of a capitalist society and economy. As important shapers of public opinion, one of their overriding functions, deriving from the profit imperative, is an ideological one: to advocate on behalf of the system that makes profit possible.

In the case of the world's dominant capitalist power, the United States, this means that newspapers and their staff can no more easily position themselves outside the ideological framework of the market economy than King Hussein's acolyte at Al-Ra'i could envisage limits to the monarch's munificence. It is no more conceivable that The New York Times, or any other mainstream U.S. paper, would one day declare itself in favour of socialism than that the Korean Central News Agency would suddenly start singing odes to market capitalism. In fact, it is somewhat less conceivable, since we have one example of an avowedly communist society and media system (China) that has shown considerable flexibility in adapting to market ideologies. The situation in Canada, Western Europe, and Australia is somewhat different than in the U.S., reflecting a more diverse political culture, more varied patterns of economic organization, and a wider range of sources of press sponsorship. Political parties and trade unions, for example, still play a leading role as sponsors of Western European and Scandinavian media; many of these systems also feature direct government intervention in the media, through a vigorous public-broadcasting sector and strict anti-monopoly legislation. In Scandinavia things are carried further still, with the regime providing subsidies "in the public interest" that offset the profit imperative to some degree for the written press. Analysis of the mobilizing imperative that prevails at a given mainstream press institution needs to be correspondingly more nuanced, though commercial considerations will almost certainly still be primary.

Do these comments unfairly demonize the profit motive? The positive aspect of a commercial mobilizing imperative should be acknowledged. Market mechanisms were crucial in establishing an important measure of political autonomy for the press, and bolstering it in the face of regime pressures -- no small accomplishment in world-historical terms. So long as the basic ideological underpinnings -- respect for private property and the corporate organization of the economy -- are incorporated, press workers may have substantial freedom to debate secondary political and economic issues (such as the actions of a given regime and its policies), and to investigate corruption and other malfeasance, even in the corporate sphere. As far as transitional media are concerned, the most impressive achievements of the press in undermining authoritarianism, or in supporting democratic forces during liberalization and political transition, are rarely ascribed to regime-affiliated media, for obvious reasons. Indeed, they tend to correlate with corporate sponsorship, since this is the most common alternative to direct or indirect regime affiliation. Daniel Berman cites Huang-mao Tien, a Taiwanese political scientist, to the effect that "before the lifting of martial law [in Taiwan], commercial pressures and network competition for popular programming rendered many government restrictions extremely difficult to implement. It was due to the fact that business goals sometimes run counter to political interests, according to Tien, that Taiwan's newspapers were able to maintain a degree of independence not found in other authoritarian systems." Berman adds: "the economic interests in a capitalist system may sometimes be the only force powerful enough to override authoritarian political directives."(33)

We should not, though, exaggerate the degree of autonomy from state or regime that the press enjoys in the market democracies. Regimes remain powerful mobilizing forces unto themselves, deploying a battery of functionaries and representatives to try to bend mainstream media -- particularly elite "agenda-setters" and opinion leaders -- to their own views and priorities. By varied means, essentially clientelist in nature, they encourage these institutions to respect rules of "acceptable" political discourse that protect powerful interests from public inspection and intervention. And regimes are important players, if arguably secondary ones, when it comes to establishing the "rules of the game" within which public discourse occurs. Its regulatory apparatus is normally held in reserve, but in times of war or national emegency, censorship and news management on a massive scale are the norm -- even in the most liberal media systems and the most recent crisis settings (for example, the conflicts in the Falkland Islands and the Persian Gulf).(34) The running battles between successive apartheid regimes and the liberal English press in South Africa provide one of the few examples of real disharmony between regime and mainstream media in an emergency situation, and even there, the press was usually careful to operate within the law.

Regimes, corporations, political parties, and trade unions or other public associations are thus the key actors determining the mobilizing imperative of press institutions the world over. But newspapers are also influenced by a range of petty mobilizers whose input may, on a given day and in a particular setting, prove significant or even decisive. In a classic authoritarian system, the petty mobilizer will likely be a functionary dispatched by the state or regime, usually to ensure a smooth translation of the regime's mobilizing agenda into daily editorial content. Occasionally, usually as a reflection of a softer authoritarian system, such functionaries may clash with editors or journalists, for reasons to be considered shortly. Regime functionaries also play a role in the market democracies, as noted. Here, though, the petty mobilizers are more likely to be corporate functionaries of one kind or another: the "advertisers, public relations officers, and commercial managers," as Ken Owen put it in the South African context, who "want to slip propaganda into the newspaper in the guise of 'news'."(35) They compete with each other for the newspaper's attention and favour (more favourable advertising terms, greater publicity for corporate products or services, and so on). Newspapers also court them, assiduously -- most obviously for the advertising revenues whose disposition they control. These varied architects and representatives of the mobilizing imperative, then, combine to exercise the greatest influence over press functioning. Indeed, the influence of the mobilizing imperative is so obvious that many media systems -- particularly those in highly authoritarian and/or underdeveloped societies -- are seen as responding to little else. In my view, though, the mobilizing imperative rarely tells the whole story -- even in classic authoritarian systems where all media of note are owned and administered by the state or regime. Other influences, priorities, and practices must be factored in -- elements that do not result directly from the newspaper's struggle for survival, nor respond to the mobilizing agenda implemented by powerful sponsors, managers, and (usually) senior editors. I group these factors and considerations under the rubric of the professional imperative, which I locate for the most part within press institutions themselves, notably at the level of journalists and editors. These are the actors who have the task of producing the day-to-day "output" of the institution, at least what can be squeezed in among the advertisements.(36) Senior editors, as already mentioned, occupy something of an ambiguous position straddling the two imperatives. On the one hand, they are the proximate architects of the paper's editorial output, and the key "gatekeepers" when it comes to maintaining the integrity and cohesion of the institution. But they are themselves neither owners nor bean-counters, and may very well find themselves on the hot seat if and when mobilizing and professional imperatives clash.(37)

There are two forces. On the one hand, there is outside interference in terms of money, influence, direct control, and so on. On the other hand, there is a corporatist spirit within the community of journalists, and professional training, which is very strong. So every competent journalist has a kind of internal contradiction.

- Boris Kagarlitsky, Russian intellectual

We had to reconcile what we construed as sensitive reporting, as far as the government was concerned, with a minimum level of integrity.

- Walid Sa'di, former chief editor, Jordan Times

Conceptions of "professionalism" are inherently slippery. But is it nonetheless possible, by now, to speak of a "universal journalist," as David Randall does in his stimulating little book?(38) There is little doubt that the art of "reporting" has established itself as a professions, and often as a distinguishable "estate," in diverse political systems around the world. With this process of professionalization, and the diffusion or imposition of western models of modernization throughout the world, has come a greater routinization of journalistic behaviour, guided by a distinctive set of professional norms, standards, and strategies. Thus, any evaluation of a "professional imperative" must see it as "part of a general trend ... toward conceptions of administrative rationality and neutral expertise," beginning in 19th-century Western Europe and the United States.(39)

The expression of such a "professional imperative" seems contingent on a diversity of other political, social, and economic forces. The version of "professionalism" propounded by U.S. media was likewise an offshoot of distinctive patterns of sponsorship and mobilization during the nineteenth century. Michael Schudson has argued, for example, that the professional values of North American journalists were conditioned by the mobilizing imperative of commercial success.(40) Advertisers replaced parties and regimes as the leading source of sustenance; advertisers wanted readers; and to broaden their constituency newspapers (and also wire services) increasingly adopted a less partisan, more "objective" tone in their coverage. The appeal to a mass audience encouraged an emphasis on human-interest issues rather than the narrow concerns of political and economic elites. Over time, these trends coalesced into a "cultural form, with distinct technical codes and practical rules," according to Hackett and Zhao. These included "the attribution of opinion to sources, the construction of information in an appropriate sequence and format (the news story), the presentation of both or all major sides or viewpoints on public issues, and adherence to prevailing standards of decency and good taste."(41)

There is little doubt that professional self-conceptions are strongly shaped and constrained by the level of development that prevails in a given society and media system. The sense of professional self-worth that journalists and editors feel tends to arise and increase in tandem with the broader development of a media system and a society itself. Certainly, underdevelopment induces a hangdog cast, professionally speaking. When the material infrastructure or finished product is ramshackle, journalism is much less likely to be perceived as an honourable career to pursue -- often with good reason, and in good measure because of the professional compromises (corruption, "moonlighting") that may be necessary to win a basic subsistence. Underdevelopment also affects the institutionalization of journalism, an important factor in instilling and bolstering professional self-esteem. The evolution of press organs into at least semi-autonomous institutions; the growth of unions and professional associations for journalists, editors, and publishers;(42) the evolution of internal "watchdogs" on press conduct -- all these may serve to demarcate the profession of journalism from occupations that otherwise might be closely related: publicist, stenographer, tout.(43)

We cannot, however, posit a simple causal link between development and professionalism. First of all, professional tradeoffs and compromises may be felt every bit as acutely in an underdeveloped media environment like Nicaragua as in a more developed one, as we will see shortly. Second, as Jae-Kyoung Lee has argued in his analysis of the "rather disappointing or even dire record" of East Asian media, "the fundamental assumption ... that economic growth will translate into a concomitant increase of press freedom must be either abandoned or radically modified." He proposes the addition of an historical variable to consider the strength of "civil society" or "the public sphere" in bolstering the professional imperative. Because newspapers "are literally grounded in the history and culture of a society, an adequate analysis of them will yield rich insights about how institutions of public communication have evolved in a country and why the country has come to have a certain type of national media system rather than other types."(44) A particularly important factor appears to be the presence or absence of an "independent" press tradition in a country's past. Another meta-environmental variable, media culture, is therefore worth factoring in; it would be difficult to examine the evolution of Barricada, Izvestia, or the Johannesburg Star without understanding something of the impact of La Prensa on the culture of Nicaraguan reporting; the role of the "fat journals" (tolstyi zhurnal) in 19th-century Russian journalism; and the formative influence of the "English model" of liberal journalism on the English-language press of South Africa.(45)

Journalists start to realize after a couple of years of experience that there is a thing called responsibility. When you write something, you should think about the people who will read it, because you can change people's lives. You should remember that some people read newspapers as though they were the only true opinions about something. You should always bear that in mind.

- Irina Petrovskaya, Media Columnist, Izvestia

Beyond the political, social, and economic influences discussed above, are we justified in isolating an ethical and epistemological foundation to the professional imperative? In recent years, commentators have begun to speak of the creation of a "global civil society" or body of "world public opinion," built around core values like respect for life, human rights, and opposition to war.(46) In the same way, global conceptions of professional journalism seem increasingly to have moved towards consensus on what might be called a "moral economy of journalism." (The reference, of course, is to James Scott's classic study of subsistence and rebellion, The Moral Economy of the Peasant.(47)) I contend that a major force shaping the professional imperative is a set of normative and ethical principles which are not simply reducible to material self-interest:

an adherence to the values and procedures of liberal democracy and the rule of law (except where law is administered by tyranny);

a relatively high degree of autonomy from state and regime(48) -- a "watchdog" role vis-à-vis ruling authorities and other locii of power;

service to readers and the public good more generally (the "social responsibility" model of press functioning, with developmentalist overtones in many parts of the Third World);(49)

consultation of a diversity of sources and accurate representation of their views; and finally,

"objectivity": the separation of fact and opinion, story and reporter, news and editorial content, with a ritualized language of "distancing" from one's subject material.

This last concept is probably the most contentious, and I would hardly deny that it varies widely across existing media systems, even western ones. It is doubtlessly more muted in European than in U.S. media, for example,(50) and may also be less prominent in media systems where developmentalist influences are strongest. Recognizing this especially highly-contested character, I regularly place "objectivity" in quotation marks throughout this work.

The expression of these core values is limited by authoritarianism and other mobilizing constraints. The surface of relations between media institutions and authoritarian regimes, for example, may be very placid for a very long time. In The Moral Economy of the Peasant, Scott likewise stresses how rare and difficult is fullscale peasant rebellion, calling it "one of the least likely consequences of exploitation ... To speak of rebellion is ... to forget both how rare these moments are and how historically exceptional it is for them to lead to a successful revolution."(51) The basic power imbalance, and the consequent "reliance on state-supported forms of patronage and assistance" that entrenches the dependent relationship with and subservient posture towards the authorities, are also enough to mute most expressions of a professional imperative in journalism. As a result, in both sets of circumstances, lesser means tend to be found of evading constraints, be they oriented to material subsistence or professional self-expression. The peasant strategies cited by Scott -- exit through migration, "raiding the cash economy," "growing symbolic withdrawal" -- strongly resemble professional strategies used to circumvent mobilizing restrictions, whether under authoritarian regimes or modern corporate management.

To see some basic tenets of the "moral economy of journalism" writ large, consider the New Editorial Profile promulgated by Barricada's Editorial Council and approved by the Sandinista National Directorate in December 1990. The drafters of the profile pledged, among other things, to move towards

a balanced journalism which breaks with the unilateral nature of information predominant in Nicaragua. That is to say, the consultation of various sources in covering news, the presentation of alternative opinions, etc., in order to gain credibility and professional quality. ... To establish a solid relationship with the public which is linked to the daily. Their minor and major concerns and demands -- whether individual or social -- should always receive privileged attention. ... To formally separate opinion from information, and to adopt a necessary distance in treatment of informational subjects. This does not imply that information should be stripped of all its political significance [intencionalidad política] ...(52)

In a very different media environment -- South Africa -- that paradigmatic English daily, The Star, proclaimed in its Code of Ethics a vision that with one (italicized) exception was in every respect typical of the consensus that has evolved among media in the developed market democracies:

1. In its reporting and comment, The Star should be accurate, fair, honest and frank.

2. The Star should aim to give all sides of an issue, by means of balanced presentation without bias, distortion, undue emphasis or omission.

3. The Star should be independent of government, commerce or any other vested interest.

4. The Star should expose wrongdoing, the misuse of power and unnecessary secrecy.

5. The Star should encourage racial co-operation, and pursue a policy aimed at enhancing the welfare and progress of all sections of the nation ...(53)

Fine words -- but also more than that, in my view. The moral economy, with its "objective" epistemological essence, responds in part to the desire of media workers to reconcile the inevitable (and primary) mobilizing imperative with their professional and ethical desire to tell the truth. We have already seen examples of the kind of dissonance that can result when journalists are asked to bend reality too far to suit sponsors' wishes. For another, consider the plight of Barricada journalist Gabriela Selser, dispatched in the early 1980s to report on the fate of the indigenous population of Nicaragua's Atlantic Coast. Thousands of Miskito villagers were being forcibly relocated away from the war zone along the Honduran border, where it was feared they would fall (or had already fallen) under the influence of contra rebel forces. Barricada's editors, said Selser,

sent me to [the resettlement camp] the day or the day after the people had been moved, supposedly to write about how nice [the camp] was. The problem was the people didn't want to live there. The women were crying, accusing the Army of having forcibly removed them from their houses. They asked us [journalists] to tell the truth: that they weren't doing well there. ... They missed the river, their trees, their houses. I remember I came back really traumatized. We had very strong discussions at the newspaper about how to focus the story on this. We managed to write a story in which everything was outlined, but sort of between the lines, in a disguised way. For example, we said it was natural [those resettled] would feel badly, but they'd get used to it. I never agreed with that [approach] ...(54)

The dissonance here was between reality as the journalist understood it, and the editorial "output" that best suited the mobilizing requirement of the sponsor -- in this case, the Sandinista Front. A rationalist or positivist epistemology (call it what one will) appears necessary in order for such a "moral-economic" crisis to arise. There must be the assumption, and the professional conviction, that reality is not infinitely malleable. Only if this is the case can that reality be seen to vary from the sponsor's requirements or preferences; only then can the gulf between mobilizing and professional imperatives give rise to anxiety, unease, or "trauma." One can see from the example, and numerous others that will be cited throughout this work, how delicate is the task of juggling mobilizing and professional considerations in the task of daily journalism: how fraught the strategy is with pitfalls; how readily it can give rise to tension and discord, and sometimes open conflict, between the custodians of the respective imperatives.

We must ask, lastly, how applicable this framework is to the media of the developed west. They are not a focus of this work, but one of their offshoots -- South Africa's English press -- very much is. Moreover, all the case-studies (as well as the supplemental Jordan study) offer examples of press institutions moving towards western models, usually as a reflection of declining or defunct regime sponsorship and the move to a market economy. We do not need to expend much energy demonstrating that the professional imperative as described is relevant to western settings, since the classical version of it originated there. But can one meaningfully speak of conflicts between the prevailing mobilizing imperative -- usually profit -- and the tenets of the professional imperative and the moral economy?

My conviction is that such a framing is valid, perhaps no less in the market democracies than in authoritarian (at least soft-authoritarian) systems. The fact that newspapers must both report on and derive the bulk of their income from large corporations (via advertising) is a situation tailor-made for quandaries and conflicts. Consider, for example, the regular clash between advertising departments, which belong to the category of "petty mobilizers," and editorial departments. Most journalists and editors know that the advertising department is indispensable to the newspaper's continued existence, and hence to the reliability of their paycheques. But journalists and editors in market systems also tend to feel that advertising -- the visible expression of the newspaper's profit imperative -- is not the primary reason the paper is read. Whatever "brand loyalty" the institution commands among readers is seen to derive mainly from the efforts of editors and reporters. Those on the editorial side regularly see themselves as resisting the encroachments of "bean-counters." Kaizer Nyatsumba, political editor of the Johannesburg Star, captures well this sometimes-fractious interplay of mobilizing and professional imperatives:

I do believe very strongly that those who run newspapers are not running charities, but business ventures. Newspapers anywhere in the world have got to be profitable and self-sufficient [n.b.: perhaps an overstatement]. But journalists anywhere in the world -- those who are regarded as serious journalists -- will be very unhappy about a situation where those who own newspapers only want them to rake in money and make lots of profits, while editorial space shrinks. It's something about which I feel quite passionately. The thinking here now is that the newspaper must make money. I have no quarrel with that, provided part of the profits made are plowed back into the paper -- to pay people well, to create more editorial space. The moment we lose space, then I think most of us will be unhappy. Because then [management] people [at The Star] would be more concerned about profits than about serving the public, and that's an important responsibility that should not be shirked at all.

The perceived encroachment of commerce into editorial deliberations was in fact central to the high-profile resignation of The Star's editor, Richard Steyn, in 1994. A number of other instances of such dissonance are cited in the South African case-study (Chapter 3); the relationship between the press and the corporate sphere in that country has been even more cozy than the western norm. More generally, radical critics of western, especially U.S., press performance have tended to focus on the intimacy of ties between mainstream newspapers and corporate and/or political elites. These critics argue, with considerable validity in my opinion, that the pressures and constraints of the profit imperative are not profoundly different, in nature or impact, from those brought to bear in more formally authoritarian societies.

The critics' views are worth exploring a little further here, since it is in their writings that we might expect to find the harshest denunciation of the idea of a "professional imperative" or a "moral economy." What objections might the radical be expected to pose to this framing, whether it is applied to the developed market democracies or underdeveloped authoritarian systems? Perhaps that the professional imperative is merely a self-delusion -- posturing of the type that any publicist or propagandist is bound to engage in, the better to harmonize reality with the warped version that is their stock-in-trade. Radical critiques do, indeed, usefully stress the range of mobilizing imperatives that help us to extend our analysis beyond authoritarian and/or underdeveloped societies. But it is notable that, to take a well-known example, the "propaganda model" of Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky(55) does not rule out the existence or validity of a professional imperative and a "moral economy of journalism." One might be surprised to find Chomsky writing elsewhere that

The general obedience of the [U.S.] media does not approach full subservience, much to the distress of "conservatives," and there is a tradition of professionalism of reporting that is also lacking in much of the world. An American journalist is as likely to give an accurate account of what he or she sees as any in the world, far more than most; though what they look for, and how they perceive it given a background of indoctrination, and what the editors will tolerate or select, are different matters.(56)

"The mass media," Chomsky told an audience in British Columbia, "are complicated institutions with internal contradictions. So on the one hand there's the commitment to indoctrination and control, but on the other hand there's the sense of professional integrity."(57) It is not difficult to find similar comments scattered throughout the work of other radical critics. Michael Parenti, for example, writes:

Journalists who believe they are autonomous professionals expect to be able to report things as they see them. If the appearance of journalistic independence is violated too often and too blatantly by superiors, this can have a demystifying effect, reminding the staff that they are not working in a democratic institution but one controlled from the top with no regard for professional standards as they understand them. To avoid being criticized as censors and intrusive autocrats, publishers and network bosses sometimes grant their news organizations some modicum of independence, relying on hiring, firing, and promotional policies and more indirect controls. They might show themselves willing to make an occasional concession so as to minimize the amount of overt intrusion. The idea of a free press is more a myth than a reality, but myths can have an effect on things and can serve as a resource of power. ... At times superiors can be prevailed upon to make concessions.(58)

From a less radical perspective, Ben Bagdikian contends that today's "journalists are not only better educated, but ... are more concerned with individual professional ethics than would have seemed possible fifty years ago. The conventions against lying, fictionalizing, and factual inaccuracy are strong and widespread. ... The devotion to accurate facts and the rarity of suppression of dramatic public events are strengths of American reporting."(59)

In sum, it appears as though a professional imperative not only figures in much radical or quasi-radical commentary; but that it actually constitutes the very ideal of press functioning which they espouse. It is the chasm between the professional imperative and professional performance that radical critics generally assail -- not the existence or validity of the imperative itself.

In the following sections, I attempt a taxonomy of the most common strategies by which journalists and editors seek to express the professional imperative under authoritarianism, and the structural conditions most likely to encourage that expression. It would be deeply misleading to extend the analysis to developed, liberal-democratic, market-oriented mass media without caveats and qualifications. But it would also be a mistake to view authoritarian and/or underdeveloped media systems as somehow sui generis, immune to the kind of conflicts between the imperatives that are more plainly visible in democratic systems. We will return to this point later in the chapter, and explore it further in the South Africa case-study in Chapter 3. For now, the question is: how do press workers, confronted with the panoply of constraints discussed, seek to counter them with a "professional" agenda of their own?

Taking advantage of splits in sponsors' ranks

With the Sandinista Front divided and dislocated after its election defeat in 1990, Barricada found the ideal moment to forge a more autonomousagenda that allowed greater breathing-space for the professional concerns staff had long harboured (see Chapter 2). Izvestia in Russia likewise seized the opportunity (and responded to the challenge) presented by the collapse of the USSR to establish itself as one of the most "professional" dailies of the post-Soviet era (Chapter 5). Newspapers the world over seek to exploit such rifts within sponsors' ranks in order to widen the professional sphere of their operations. What are the sources of these splits in sponsors' ranks? Often personalistic power struggles seem the most prominent consideration. They can also result, though, from differing visions of the relationship between regime and civil society, especially as this pertains to the desirable scope of civil freedoms (note the clash between duros and blandos -- hard-liners and soft-liners -- isolated by O'Donnell and Schmitter).(60) Whatever its roots, disunity or factionalism among sponsors is a leading contributor to periods of liberalization and "thaw," almost always exemplified in the media above all other fora. At such times, the taboos that buttress authoritarian rule are suddenly opened to transgression, and journalists move to the forefront of the societal ferment. Thaws, of course, can unleash avalanches -- the point at which the analyst might, with the benefit of hindsight, locate the onset of a fully-fledged political transition. It cannot be too strongly stressed that the behaviour of the media, especially the press, at such points may be crucial to the liberalization or transition as a whole. It is undeniably central to any understanding of transformations those press institutions themselves experience.

The South African case-study offers a somewhat novel variant on this theme. The split in sponsors' ranks occurred at the level of societal elites broadly viewed, rather than among the owners and directors of English press institutions per se. A substantial component of that elite, indeed the economically dominant group -- English Whites -- spent more than four decades deeply estranged from their politically-dominant Afrikaner counterparts. The result was the positioning of the English press as an opposition voice, one that took pride in its "professional" sensibilities as against the overtly propagandistic role of Afrikaner media. There is much more to the story of press-as-opposition, which will be considered at length in Chapter 3; but it was clearly the lack of elite unity that permitted the English press to play whatever critical and progressive role it did in undermining the apartheid system.

It is also possible to speak of a split among sponsors as reflecting divided priorities among groups that otherwise appear coherent or unified. Barricada in Nicaragua offers a notable example. Its autonomy experiment relied above all on uncertainty and dislocation within its Sandinista sponsor: even those figures (such as former president Daniel Ortega) who would later prove decisive in the dismantling of that project initially felt bound to support it. Likewise, when the ortodoxo contingent established hegemony and an artificial "unity" within Sandinista ranks, the professional space opened to Barricada was doomed, and finally -- in October 1994 -- closed.

Exploiting a "soft" authoritarianism

"Soft" authoritarianism generates a host of challenges and constraints -- but also a number of opportunities -- that strongly influence the expression of the professional imperative. The Sandinista regime in Nicaragua, for instance, was an unusually tolerant and open one, providing a space for opposition media unusual not just for left-revolutionary regimes in this century, but even compared with liberal-democratic societies in conditions of war or national emergency. The effect on the FSLN's official organ was multifaceted. The paper was able to develop its own sense of professional identity -- and then to lobby the leadership of the Front, successfully, for greater institutional room to express that identity. These negotiations presaged the more dramatic transformations of January 1991; they would hardly have been countenanced in, for example, Castro's Cuba, the left-revolutionary society that was closest to Nicaragua in both the geographic and the political sense. Unknown elsewhere, too, was the existence of a broad range of opposition media throughout the Sandinista years in power. The most prominent opposition voice during the revolutionary decade was Violeta Chamorro's La Prensa, an institution with deep roots in the country, and a leading player in the struggle against the Somoza dictatorship. After July 1979, La Prensa sundered internally, giving rise to the pro-revolutionary El Nuevo Diario and a more conservative version of La Prensa that came out in strong, often bilious opposition to the Sandinista authorities. At the height of the contra war, La Prensa went so far as to send senior editorial staff to Washington to lobby for aid to the rebels, a near-treasonous action that led to the paper's closure for 15 months. For most of the revolutionary decade, however, La Prensa served as Barricada's principal opponent and competitor. This "reflex relationship" between the two papers, as Barricada's director Carlos Fernando Chamorro referred to it, was a powerful spur to Barricada's professional imperative; staffers spoke of a sense of disorientation in both mobilizing and professional senses when the paper was banned.

South Africa under apartheid should similarly be classed as a "soft" authoritarianism, at least as far as the White opposition and English-language press were concerned. Certainly its repression was serious and systematic enough to cripple the development of an independent Black press. But the degree of latitude the regime permitted intra-elite opposition was again unusual for an authoritarian polity. It was certainly decisive in enabling the press to play the role that it did in confronting apartheid and developing an "English model" of liberal-democratic journalism. The third case-study country examined in this book, Jordan, likewise merits the "soft" designation. Even before 1989, the country had a reputation as one of the most liberal in the Arab world, perhaps matched only by Kuwait and antebellum Lebanon. Regime control over print media was diffuse rather than direct, and the system of prior censorship and state agents in the newsroom was a sporadic rather than pervasive feature. All these factors were vital in allowing the regime-affiliated press to take halting steps towards greater independence, as described in Chapter 4; and in permitting the rise of tabloid and political-party media after the liberalization process began in mid-1989.

"Piggy-backing"

When reformist impulses arise in authoritarian systems -- if the blandos gain the upper hand over the duros, usually as a reflection of wider popular opposition and unrest -- then newspapers and their staff will often be quick to seize the opportunities presented to downplay mobilizing considerations and expand the reach of the professional imperative. They will often seek to "piggy-back" on the forces of reform, through a variety of overt and coded strategies. For example, journalists may selectively cite examples from the mythologized past in order to align themselves, in readers' eyes, with reformist or liberalizing elements. (They may also, of course, align themselves with the most reactionary elements -- but not, I would argue, on grounds of professional principle.) In the best-known cases, the Soviet Union and China, the linguistic intricacy of these strategies spawned an entire cottage industry devoted to reading the tea-leaves of the "totalitarian" press, looking for cracks in the elite edifice.

Another "piggy-backing" tactic that deserves consideration is the exploitation of a privileged relationship with a powerful or dominant regime actor -- usually manifested in the relationship between the actor and the press organ's director or chief editor. The degree of professional space granted to newspapers under authoritarianism often correlates directly with the trust established between senior figures at both the regime and the institutional level. Favoured editors and directors may use their greater leeway to bolster the professional imperative and institutional autonomy of their paper -- even when this irritates or alienates other important regime players.(61) Much of the success of Barricada's autonomy project in the early 1990s can be ascribed to the proximity of its director, Carlos Fernando Chamorro, to the the inner circles of Sandinista power. (Chamorro even headed the FSLN's Department of Agitation and Propaganda for a time in the mid-1980s.) Partly as a result, Barricada was never exposed to the kind of prior censorship visited upon the other Nicaraguan dailies in the 1980s (even the pro-Sandinista El Nuevo Diario); the chief censor during this period, Nelba Blandón, referred in an interview to "a relationship of trust" existing between the Front and its official organ under Chamorro's direction. As well, it is unlikely that Barricada's FSLN sponsor would have been willing to grant the far-reaching independence that it did in December 1990 to a paper headed by a more mercurial, less sympathetic figure than Chamorro.

In South Africa, the degree of independence from sponsors' interference that M.A. "Johnny" Johnson, editor of The Citizen, enjoyed was unparalleled not only among pro-regime media, but anywhere in the English-language press as well. The personal relationship between Johnson and Perskor chair Koos Beytendag appears to have been crucial to the arrangement. According to Senior Assistant Editor Martin Williams, Johnson "has no power without the chairman. It's the relationship between them -- that's where the power exists. If the chairman says go, he walks. But as long as he has that relationship with the chairman, he doesn't go."

A number of other examples of "piggy-backing" can be cited from media systems other than the case-studies profiled in this book. In his analysis of The Russian Press from Brezhnev to Yeltsin, John Murray offers an interesting anecdote about how personal clout can allow editors, at least, to override mobilizing requirements -- and pave the way for others to do the same. The example is drawn from the newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda during the early Khrushchev era (1957). Murray writes that

One journalist, [Alexander] Krivopalov, was working as duty-editor in the news-room when a TASS [state wire service] communiqué that would have filled an entire newspaper page arrived on his desk. Customary practice had been to print TASS communiqués in full, often, moreover, on the page and position on the page indicated on the TASS notice. About to proceed, Krivopalov was interrupted by the editor, Khrushchev's son-in-law, [Alexei] Adzhubei, who looked at the official notice and expressed his indignation at having to devote so much space to it. He then told Krivopalov to reduce the length of the notice by five times before printing it. Krivopalov, with grave misgivings, did so. The edited résumé appeared and neither Adzhubei nor Krivopalov were fired, a probable outcome prevented only because of Adzhubei's favoured status at the time, according to Krivopalov. Subsequently, other papers followed suit and soon TASS began to shorten their communiqués.(62)

Adzhubei went on to edit Izvestia, where the "close family connections between Khrushchev, the top leader at that time, and our editor-in-chief" likewise gave the paper added clout and breathing room, in the recollection of Stanislav Kondrashov (see Chapter 5). The role played by People's Daily editors during the Tiananmen events of 1989, when "the state's most important propaganda tool emerged as a virtual flagship of rebellion," was made possible by the unique trust extended to the party's time-honoured mouthpiece. This had manifested itself, over time, in a degree of structural separation between sponsor and institution -- a partial but unusual autonomy that the People's Daily then used to press for a more professional journalism and the political reformism that would entrench it. Frank Tan's careful study zeroes in on the right aspects of institutional functioning, in my view, and draws conclusions that seem congruent with the arguments advanced here:

In order to understand how disagreement with the party line could manifest itself in the People's Daily, it is necessary to know something about the paper's internal operations prior to the suppression of the student movement and the corresponding repression of the press in general. An important underlying principle at the People's Daily has always been that leading editorial staff, from the chief editor and his deputies to the heads of departments and the editors in charge of putting together specific pages, have had more authority and discretionary powers than one might expect. True, they attend regular meetings and consultations with propaganda authorities, receive direction and orientation from written materials, and sometimes get specific instructions to publish certain things, but the editors make most day-to-day decisions on whether, where and how their reports are used.

According to Tan, "The latitude for editorial judgments built into the organization of work at the People's Daily did leave room for editors to stray from the official line. They seldom did so, however, because their training, socialization and positions made them staunch loyalists and devoted propagandists. But a radically different situation had arisen by the spring of 1989," drawing journalists and editors towards a much more activist orientation, and incidentally raising the question of how "staunch" and "devoted" the loyalty to their sponsors truly was.(63)

Exploiting the foreign dimension