The Heart of the Matter:

Bogotá

by Adam Jones (1994)

[From Guns and Orchids: A Journey through Colombia (unpublished

ms.)]

Military police conducting body-searches,

Bogotá. Photo by Adam

Jones.

The

state of emergency goes into effect on the evening of May 1st. No-one in

Bogotá pays much attention. It is, after all, the third suspension

of the constitution in the past two years, and it results in no noticeable

increase in the number of armed security personnel in the streets, nor

in the frequency of hands-against-the-wall body searches.

The

state of emergency goes into effect on the evening of May 1st. No-one in

Bogotá pays much attention. It is, after all, the third suspension

of the constitution in the past two years, and it results in no noticeable

increase in the number of armed security personnel in the streets, nor

in the frequency of hands-against-the-wall body searches.

The emergency measures are aimed, instead, at circumventing the six-month

maximum allowed by the constitution for criminal cases to come to trial.

For some days, the papers have been full of government and editorial hand-wringing

over the impending release of more than eight hundred accused delinquents

charged with kidnapping, drug trafficking, "terrorist" activities or common

crimes whose cases have been mired at a preliminary stage in the sclerotic

Colombian judicial system. The state of emergency will tack on a ten-day

grace period to the constitution's six-month limit. Government spokesmen

are front and centre pledging that the measures will not be abused. (Nor

will they be effectively used: I return to Colombia some weeks down the

line to find more editorial venom, criticizing the release of most of the

eight hundred.)

I arrive in Bogotá on a direct bus, the only one of the day,

from Ambalema. Five hours to travel a hundred and fifty tortuous kilometres,

up mountain ranges that snatch the breath from your lungs and fill the

bus with vapour. That's five hours on a good day - without the treacherous

conditions caused by the heavy rains of the night before. It ends up taking

us six, with the extra hour spent in an impotent slither at the bottom

of a muddy thirty-degree grade. The driver chuckles as he manoeuvres the

bus backwards, sideways; he succeeds only in sliding us up against a forty-metre

bank of glistening earth at the side of the road. I look out the window

nervously. Armero has taught me something about the power of mud. "Maybe

you should move to the other side of the bus," a Colombian traveller

offers from across the aisle.

Not a bad idea. But rescue is at hand. The driver's assistant has managed

to squeeze himself through the narrow crevice between doorway and mudwall,

and has made his way to a construction site half a kilometre down the road.

I watch his heartfelt pleading, and then a stolid bulldozer detaches itself

from the work crew and huffs over to us. A cable is attached; our wheels

come loose with a grateful sucking sound; and we are on our way. My only

injury is a bruised knee, the result of leaping back onto the moving bus

after jumping out to capture the scene on film. "Nice souvenir!" the driver

yells, giving me a thumbs-up. I rub my kneecap ruefully.

We cross the boundary of the capital district a good hour before we

reach the Bogotá main terminal. Like most cities in Colombia, Bogotá

has boomed and sprawled at an epic pace over the last thirty years, swallowing

up a number of outlying towns and villages along the way. So my first glimpse

of this monster - the only city on the trip that truly makes me nervous - is

strangely pastoral. There are large, empty fields with only a few cows

grazing. Some serious land speculation is likely going on: many of the

fields sport signs bearing cautions, along the lines of, THIS PROPERTY

NOT FOR SALE. DO YOU UNDERSTAND? NOT FOR SALE. UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES - But they are hardly productive tracts, and my guess is that the bovines

are there to preserve the land's "in-use" status, as insurance against

seizure or tax hikes. When prices rise high enough in these outlying areas,

you can bet the cows will head to the slaughterhouse, and condominiums

will graze instead.

The suburbs proper are filthy. I mean sloppy, rubbish-strewn, stray-dog

filthy. Devoid of everything but the limitless energy of the new arrivals,

determined to make it big (or at least bigger) in their squalid corner

of La Capital. And it is not long before the notorious traffic of

Bogotá clamps down on us like a rabid hound, refusing to let go,

no matter how the driver wheels and honks and curses. My head spins from

the belching diesel fumes. Grey, grey everywhere on this drizzly winter

morning.

We pull, at long last, into Bogotá's gleaming transport terminal,

still a long way from downtown, and I plod along the busy halls just to

stretch my legs. It's Saturday. I'm coasting on the seven thousand pesos,

or thereabouts, that I saved in Ambalema by shifting from the Motel Los

Ríos to the Barcelona. With the banks closed until Monday, it's

a choice between springing for a taxi into town or splurging on that very

handsome and, really, absurdly cheap Guns N' Roses T-shirt hung invitingly

in the window of a terminal boutique.

Half an hour later, G N' R shirt safely stowed, I'm stuck again in an

infernal traffic jam - this time aboard a Bogotá public bus whose

shock absorbers gave up the ghost around the time of Simón Bolívar. The driver takes a perverse pleasure in riding up over the curb on

every sharp corner. My knee bangs painfully against the seat in front.

The bus starts half-empty, but is soon filled to bursting with bogotanos.

One of them is a speechgiver. He brandishes hospital documents and a tattered

bit of X-ray film to back his tale of woe, and he rakes in a decent haul

from the passengers. There will be more evidence of this over the next

few days: the surprising generosity of bogotanos, whose big-city

aloofness melts in the face of an outstretched hand.

"Gringo! Your stop!" The driver's yell startles me into action, and

the other passengers chortle indulgently as I squeeze out the back door

... and smack onto Carrera 10, probably the busiest street in Bogotá,

a crazy tangle of taxis and busetas jockeying for position as they

inch up the boulevard. I survive this first thirty seconds in the heart

of the jungle, and pause across the street for breath. Cool air here, almost

fresh; we are nearly three thousand metres above sea level.

Once past the sidewalk stalls and road-repair crews, Bogotá exudes

a curiously genteel ambience. It's the tail end of lunch hour in the city

centre, and the scene is something out of the 1940s. Respectable-looking

businessmen in pinstripes; solid brownstone architecture, mingled with

the occasional colonial flourish. If there are thieves and pickpockets

everywhere, as the stories suggest, they're well-hidden.

It is a ten-block walk to a hotel in La Candelaria, the colonial core

of Bogotá, and once in the vicinity I circle aimlessly, unable to

register the street numbers in my muddled brain. A high, keening headache

is setting in. It's the altitude; and besides, I'm famished, the bus having

left Ambalema well before my stomach woke up for breakfast. It feels like

the dregs of a hallucination, the tenth hour of an acid trip when all that's

left is a body-buzz and a vague mental queasiness.

The foyer of the Hotel La Concordia is set at the end of a long, dank

hallway. The keys behind the desk have HOTEL GRAND embossed on them. And

perhaps it was grand, once; it has the same down-at-the-heel faded dignity

of much of the downtown core. The rate of decay is greater within the walls,

though. The cherubic young woman proprietor shows me to a single room.

It's tiny and rank with mildew, but somehow appealing: the first carpet

I've had in a Colombian habitación; the first wallpaper;

and the bed is comfortable and well-blanketed.

Then there's that hot water the guide spoke of. God, what a luxury that

will be, after a month of cold showers ... not. The lady at my elbow

grimaces. "Sorry. Only cold water now." And there's no current in the electric

socket, and the woman who's supposed to provide a laundry service has mysteriously

absconded, hasn't been seen for days, and that water is cold, baby

- so cold it's almost scalding. But it's three bucks a night, it's central,

and it will be home for the next week-and-a-half.

Bogocentrismo, they call it here: the Colombian equivalent of

"all roads lead to Rome." There are local variations on the theme, of course.

The Colombian archipelago, as mentioned, has spawned a powerful regionalism

centred on the country's other major cities: Medellín, Cali, Barranquilla,

Bucaramanga. So Bogotá never attained the singular status of a Lima

or a Buenos Aires, arrogating to itself the lion's share of the financial,

political, and cultural resources of the land.

But the capital is still a world apart. It is four times larger than

any of its rivals, and growing out of control. With its demographic edge

and political supremacy, it gives off a haughty air, a conviction that

its ways and attractions are several notches above anything its baby brothers

can offer.

This is a fairly recent occurrence. A tour through the city's perfunctory

Museum of Urban Development shows a mere nucleus of today's metropolitan

tangle in the early twentieth century. In the late 1700's Bogotá

had only 17,727 inhabitants, and was outstripped even by Ambalema. A lithograph

from the 1820s, sketched from the high hills that bound the city to the

east, looks like a vista of an English country town. La Candelaria is still

about all there is; the savannah stretches, empty, many kilometres into

the distance. As recently as 1938, Bogotá had fewer than 400,000

inhabitants.

The explosion came in the latter half of the 1940s. The city's industrial

growth began attracting peasants from across the land, and that pull was

accompanied by the "push" of La Violencia, the phenomenally bloody

civil war that, in less than a decade, turned Colombia from a predominantly

rural country into a predominantly urban one. In 1954 the capital district

came into being, and the tide of migrants continued, filling in the wide

reaches of the savannah.

The first morning in town Sunday I join the pilgrims to the church of

Monserrate, five hundred metres above the city proper, up a winding trail

dotted with hawkers and juice stands. It's another grey day, but Sundays

are the only time it's safe to walk up the hill alone. Safe from thieves,

that is; altitude sickness is another matter. Whether it's the thin air

or the cigarettes or both, I find I can walk only a couple of hundred metres

before sagging at the side of the path, heart pounding, head ringing.

Halfway up the hill is the most expansive view I will have of Bogotá:

Candelaria and the Centro Internacional, the central business district,

below and to the left; the wealthy northern suburbs off to the right; and

everywhere else that anonymous low-built sprawl, with autoroutes disappearing

into the haze like Nazca Lines.

Near the top - after one or two dispiriting false summits - the clouds close

in like the embrace of your least-favourite aunt. It begins to rain, then

to pour. I take shelter with dozens of laughing bogotanos under

the leaky eaves of a food stall. It's nearly an hour before the weather

lets up enough to continue.

At the mountaintop church I offer a silent prayer of thanks for my leather

jacket. It had been a sweaty encumbrance on the walk up, and is a godsend

now. Visibility is perhaps fifty metres. I warm myself with a cafe tinto

and a smoke, and decide to wait out the drizzle. Not a chance. After another

hour, with the afternoon waning and my stomach growling, I trot back down

the clammy steps to Avenida Jiménez and the comparative warmth of

the hotel, the smell of wet leather filling my nostrils.

With the murderous traffic, Bogotá is a city for walking. I

spend some time watching people and pigeons down at the Plaza Bolívar.

On the north side of the square, an immense reconstruction project is underway:

the Palace of Justice, seized by M-19 guerrillas in November 1985. With

the government paralyzed by the crisis, the army decided to make plain

who was boss. It mounted the crudest of armed assaults on the Palace knocking

aside the gates with armoured personnel carriers, and killing ninety-five

people. The dead included every guerrilla inside (among them, most of the

leadership of the M-19), twelve Supreme Court justices, and numerous staffers,

hangers-on, and visitors. The building caught fire and was left a derelict

shell for years.

Away from the plaza, Simón Bolívar's stamp is everywhere.

There is the Quinta de Bolívar, a luxurious villa donated to the

Liberator by grateful municipal authorities. Rejection would come later,

not long after the attempt on Bolívar's life in 1828, which saw

him spirited out the rear window of his house just off the plaza that now

bears his name - saved by Manuela Saenz, his mistress. (Bolívar took

refuge under a nearby bridge, where legend has it he contracted the lung

ailment that killed him.)

The house in which the assassination attempt took place still stands,

as do Saenz's own, more modest dwellings. She outlived Bolívar,

and was among the handful that stayed true to him to the end. Reading J.B.

Trend's Bolívar and the Independence of Spanish America,

I'd found myself as fascinated by Saenz as by Bolívar himself. Among

other things, she authored what must be the most brutally amusing "Dear

John" letter ever written - to the English husband she abandoned for Bolívar:

No, no, no! No more, man; for God's sake! Why do you force

me to write and break my resolution? What do you gain by it, except the

pain you give me by telling you No a thousand times? Oh, sir! you

are excellent, you are inimitable. I will never say anything except how

good you are. But, my friend, to leave you for General Bolívar is

something; to leave any other husband without your good qualities would

be nothing. And yet you think that I, after being the General's lover for

seven years, and with the absolute certainty of having his whole heart,

would prefer to be married to the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost or the

Holy Trinity! If I regret anything, it is that you were not even better

than you are, so that I could have left you all the same. I know quite

well that nothing can unite me to him under the auspices of what you call

honour. Do you think me less honoured because he is my lover and not my

husband? Oh, I don't live under the social preoccupations invented for

people to torment one another! Leave me alone, my dear Englishman. We will

do something else: In heaven we will be married again; but not on earth.

Do you think this is a bad arrangement? If you do, I can tell you that

you are very difficult to please. In the heavenly country we will live

an angelic and wholly spiritual life (for as a man you are a bore). There,

everything will be as it is in England; for the monotonous life is reserved

for your nation (in love-making, I mean; for in other things, who are cleverer

at shipping or commerce?). You prefer love without pleasure, conversation

without wit, walking slowly, greeting with reverence, getting up carefully

and sitting down, joking without laughing. These are divine politenesses;

but I, miserable mortal ... I want to laugh at myself, at you and at all

those serious English ways. How badly I should get on in heaven! As badly

as if I went to live in England, or Constantinople; for the English give

me the idea that they are tyrants with women, though you were not one with

me, but certainly more jealous than a Portuguese. That is not what I want!

Have I not good taste? But joking apart: politely and without a smile,

with all the seriousness, truth and purity of an English lady, I tell you

that I will never come back to you! You, Church of England, and

I an atheist: that is the strongest religious impediment; and the fact

that I am in love with someone else is a greater and stronger impediment

still. Don't you see how formally correct my thoughts are?

Your invariable friend, MANUELA.

In the margin of her rough draft, she added: "N.B. My husband is a Catholic,

and I was never an atheist; only the longing to be separated from him made

me write like this."(1)

It is a city that defeats the most energetic efforts to see everything

at a go. Impatience can be fatal when crossing the nervewracking main streets,

where a red light only sometimes translates as "Stop." I resolve to take

it easy. There is a trip to be made to the opulent northern sector - to Embassy

Row, where a bright Canadian flag flutters in the breeze, and where I can

read two-week-old copies of the Toronto Globe and Mail. They report

the inconceivable: the Montreal Canadiens, my heroes, defending Stanley

Cup champions, have been bounced from the first round of the playoffs by

their old nemeses, the Boston Bruins. At least the sun is shining when

I return to the streets.

There are dangerous parts of town, the guides say, and I edge into them

with some trepidation. But as in Medellín, no-one pays me the slightest

heed, unless it's to offer a smile and try out their halting English on

a foreign visitor. There are scruffy street-people on many corners, but

they have some dignity, and are not threatening in the least.

It's on a

stroll through one of the no-go zones, on Calle 21 to be precise, that

I spy a knot of men standing outside a doorway. A couple are peering eagerly

inside. I join them for a peek, and ...

Have you ever wondered what a whorehouse looks like inside? I know I

have.

But this is more like a warehouse than a whorehouse. It's late afternoon,

and the place is packed with the kind of crowd that might gather at the

local pub: businessmen in suits, nervous-looking student types, all of

them jostling in the hallway or sitting peaceably on benches against the

walls. Woven through the crowd are the main attractions: a couple of dozen

whores in skimpy dress, chatting with customers or each other, cadging

the occasional cigarette but otherwise holding back from the hard sell.

I buy a beer from a surly bloke in a booth. Seven hundred pesos - more

than twice the price at your average corner café. Then I settle

back to watch the action. It's all unusually sedate and civilized - more

like a high-school prom than a den of iniquity. And like the prom, it's

up to men to make the first move, while ladies wait for an invitation to

get horizontal. Occasionally one brave soul gathers himself for

a proposition, and the pair depart for the rooms upstairs.

I strike up a conversation with my bench-mate. He's Rafael, 45, with

dark Indian features. He guzzles what is clearly not his first beer with

a quiet intensity. "It's a strong name, yours," I tell him, and he puffs

out his chest, pleased. "There are no fewer than four - four! - cabinet ministers

with this name." He isn't one of them. He paints cars for a living, which

explains the flecks on his faded suit.

"You're from Canada? Ah, a beautiful country, they say. All those waterfalls.

Niagara."

How often do you come here, Rafael? "De vez en cuando. Now and

then. It's very expensive! Ten thousand pesos for an hour with these women!

But such beautiful, beautiful women." His eyes water as he surveys the

room.

I find myself wondering what he would be like as a client. He is not

the most attractive of men, and is perhaps drunk to the point of impotence.

But he's more interested in window-shopping for the moment, and he is good

company. From his no-doubt-paltry resources, he insists on buying me a

beer and showing off his isolated phrases of Italian and German. "Say something

to me in English!" he commands, and I tell him, "It is good to come to

a strange city and find a friendly person like you who offers me a drink."

When I translate it for him he nods earnestly and clasps my hand: beer-buddies

for life.

"You're not going to take a woman? Who would you have if you felt like

it?" That puts me on the spot. I mention the young woman sitting in front

of us, immersed in conversation with an eager male who looks about sixteen.

For that matter, so does she, but she stands out in this crowd. She is

dressed much more casually and conservatively than her co-workers: jeans,

a printed blouse buttoned to her throat. Black hair cascades Niagara-like

down her back. "I think she's very appealing, but it's hard to think of

her in a sexual way," I whisper to Rafael: the woman is only a couple of

metres away. "She's more like a younger sister. Or" - remembering Claudia

in Medellín - "a younger brother." It's the cheapest (and probably

most boorish) of jokes, but Rafael erupts in gales of laughter, and draws

a few stares.

After a while I excuse myself and wander back to the hall. A number

of whores are gathered there, in cramped quarters with men arriving and

exiting. One touches my arm lightly as I walk past. "Want to buy me a beer?"

She is a Black woman, full-breasted and gorgeous. Yeah, I tell her,

but I don't have the money for much more. A couple of thousand pesos. What

I'd really like is to ask her a couple of questions. Five or ten minutes

of her time - will two thousand cover it? She shrugs: "Sure."

I fetch the beers and we detach ourselves from the throng, talking quietly.

She is from Buenaventura, the largest port on the largely Black Pacific

Coast of Colombia. "My name's Consuela. I'm twenty-four. Two young kids,

the father isn't around." She looks distracted, scanning the crowd for

more promising clients as she answers my queries.

Why is she in the trade? "The money is great. I work when I want. The

house gets its cut from the extra that guys pay for the room, and from

the markup on the booze."

What does she think of the guys who come here? She shrugs. "It's natural,

I guess. They're looking for a bit of company. They don't expect me to

fall in love with them." What are her ground rules? "A condom always, always.

And I won't" - the Spanish word is vulgar, so she mimes the action, sucking

on her finger. "They can't do that to me, either."

She has her regular customers, of course. And she has a lover, a man.

Does he know what she does for a living? "Sure. But he knows the money

I'm making. And he also knows there's a part of me I save for him, that

I won't share with anybody else." She is a devout Catholic, she tells me,

attending Mass every Sunday.

A few days before I left Canada I'd bought the latest issue of The

New Internationalist, the progressive monthly with a Third

World focus. The theme of the issue was prostitution, and the articles,

all written by committed feminists, offered a slant very different from

the standard. In an article titled, "Prostitution: soliciting for change,"

Nikki van der Gaag notes that "Prostitution is one of the few ways in which

women with no other skills and little education can earn a living." A Canadian

whore tells Erica Scott that "In order for women to be truly free sexually

they have to have the right to say 'no' and also to say 'yes' but on their

terms. It's not about sex. It's about power. Women become prostitutes because

they decide to go for the best deal for the amount of time they put in

- the money is good. It's right up there with being a lawyer." In a Third

World country, it arguably beats hell out of a twelve-hour shift in a cafeteria

kitchen. (Or the male equivalents of prostitution, work as a sicario

or petty drug-dealer or emerald-miner.)(2)

The greatest threat to prostitutes, perhaps, is not anything ignoble

or debilitating in their labour - AIDS aside, and whores everywhere are among

the best-informed and most rigorous about disease prevention - but the police,

who harass, molest, arrest and exploit them with near-total impunity. To

the police threat must be added - in Colombia at least - the attentions of

right-wing death squads, who often view themselves as vigilantes of public

"morality." The thugs who toss grenades at street-kids are the same ones

who co-ordinate drive-by shootings in the red-light districts, to "cleanse"

the streets of delinquent elements - like the single mother trying to earn

enough for her family's keep by providing solace to lonely, curious, or

alienated men.

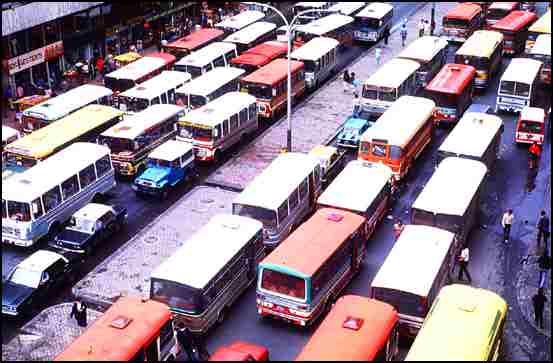

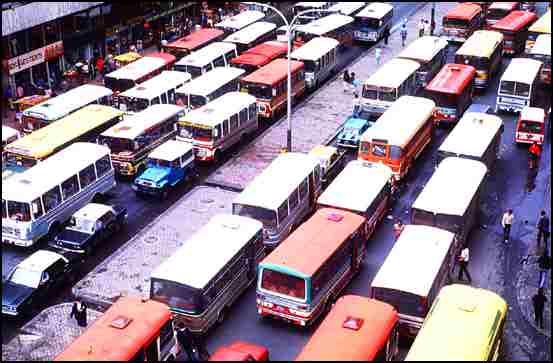

Bogotá traffic (courtesy of Lonely Planet Publications)

Friday is one of those goddamn days. It begins with the obligatory

arctic shower, which is getting harder and harder to face, and a couple

of meat empanadas from a sidewalk stall. Then, guidebook instructions

in hand, I head down to what may be the most congested intersection in

the city - Avenida Jiménez and Avenida Caracas. I stand on a traffic

island in the middle of the bleating, careening mayhem, waiting for a bus

bound for Zipaquirá in the north. It's said to run every fifteen

minutes.

Half an hour later, I'm still standing there, feeling my freshly-washed

hair turn to razor-wire, wondering what my chances are of contracting irreversible

pulmonary damage. A few last broadsides of black diesel smoke, and I've

had enough.

"The bus to Zipaquirá? Not around here," a gentleman tells me,

back on the sidewalk. "You have to catch it up around Calle 80." About

seventy blocks north.

I hop a bus that lumbers through the insane traffic and then, around

Calle 75, veers west into unknown territory. Uh-oh. "You want Zipaquirá?"

a young woman offers from the seat in front. "Best to get off here and

walk over to the Autopista Norte. Down that street, over the bridge ..."

It's raining lightly, enough to turn the streets slick, as I slosh along

to the northern highway and finally flag down a "Zipa"-bound bus. Already

my head's spinning, my chest aches. It's not yet noon.

The rain gives Zipa's outskirts a ghastly pallor. Even the guidebook

concedes that the city, fifty kilometres from downtown Bogotá, "is

of little interest." The reason to come here is to see Zipa's claim to

fame: a massive underground cathedral, carved out of solid rock-salt in

a mountain that, it's said, has enough of the mineral to meet the world's

salt requirements until the end of the twenty-first century, even after

a hundred years of steady exploitation. "A monumental work of engineering,"

the guide glows. "The huge interior is some 25 metres high, and is capable

of holding 10,000 people."

But where is it? Underground cathedrals don't exactly leap out

at you, and the guide is of little help: "The cathedral is a 20-minute

walk uphill from the centre of town." Where, for that matter, is the centre

of town? Zipa is spread out like any aimless Third World blue-collar suburb,

with the added disadvantage that any street into the hills to the west

of town seems to loop back on itself after a couple of hundred metres.

The rain falls steadily. I find myself muttering curses, getting only the

vaguest information from passersby: a sweep of the arm, "Up there, over

there." Finally one pleasant young man adds an additional, crushing piece

of news. "The cathedral? Oh yes. It's closed."

Closed? Closed? The only reason in the world to come to Zipaquirá

has decided to go on holiday? Has the roof fallen in? My grumbling is a

sure sign of blood-sugar crash - those breakfast empanadas are ancient

history - and so I repair to the nearest restaurant. The waitress, at least,

has the good grace to make flirtatious eyes at me. Her name is Marta, and

she brings me really a very good tamale, wrapped in a steaming banana

leaf. Should I make a pass at her? And then what?

Belly full, it's back to the street. There is a piece of graffiti splashed

over the wall opposite. Nothing from the M-19 or FARC, this time. It's

the plea of a lovelorn fool: S. I am an idiot. Please forgive me. William.

The day nods in melancholy approval.

Finally the route to the cathedral becomes clear, but as soon as I round

the last bend, I can see my earlier informant was spot-on. A chain bars

the path; there's a small sign reading, THE CATHEDRAL IS CLOSED. "Until

July," says a guard at the nearby booth.

"What's going on? Is there some danger?"

"No danger."

"Well, isn't there anything at all to see up there?"

The guard shakes his head, and his eyes add: It's an underground

cathedral, dummy. What else could there be to see? I slouch back to

a main road, and am grateful when a Bogotá-bound bus rolls immediately

into view.

Walking bleakly along Calle 19, leather jacket turned pulpy from the

rain, my eyes alight on a bold newspaper headline I'd somehow missed that

morning: DESPENALIZAN USO DE DROGAS. What!

I fumble for change and run off to a café to read the astonishing

news. By a five-to-four decision, the Colombian Supreme Court has ruled

that the possession and consumption "for personal use" of marijuana, hashish,

cocaine, and hallucinogens will cease, as of midnight tonight, to be a

crime in Colombia. Restrictions on the production and sale of drugs will

remain; but the Court has ruled that jailing someone thirty days for a

first offence, up to a year for a second, is a violation of Colombians'

constitutional right to "privacy, autonomy, and the free development of

the personality."

The justices in the minority protest that the legalization of drugs

is a violation of the constitution's equally-entrenched guarantees for

the rights of the family, "and, especially, of citizens' right to live

in peace." Prominent police officials add to the criticism, claiming a

bit dubiously that a high percentage of assaults and homicides in Bogotá

"are carried out by persons under the influence of hallucinogenic substances."

(The real culprits, one suspects, are booze, and possibly glue - both legal.

And then there are those carrying out homicides not under the influence

but under orders ...)

I pore fervently over the report in El Tiempo, the conservative

(though Liberal) Bogotá daily, and it's all I can do to keep Handel's

Hallelujah Chorus from bursting forth. My first thought is, Oh, man,

is the U.S. ever going to be peeved. That's certainly one mark in the

Supreme Court's favour. Then it occurs to me that a real blow has been

struck for individual liberty and common sense. This tempers my exhilaration

somewhat. Neither liberty nor common sense has ever been much in vogue

among the Colombian political class, and it's reasonable to expect an immediate

counterattack from the bastions of privilege.

It will begin the next morning, with newspapers full of vitriol

- editorial and otherwise - against the Court's judgment. OVERDOSE, El Tiempo

blares on its front page, lining up an impressive array of politicians,

security officials, and church leaders who join in "unanimous condemnation"

of the decision. President Gaviria is heard to mumble something about a

constitutional amendment that will recriminalize drug use. And from the

U.S. there is, predictably, damnation and dismay.

But all that's tomorrow. First I have to get through the evening,

and since the Court's decision doesn't take effect until midnight, I'm

stuck with presently-legal drugs to take the edge off the restlessness

and gloom that have descended over the course of the day. Friday night.

Normally I'd be getting ready to head down to the Fogg N' Suds, to chat

with Andrew or Elvis behind the bar. It would be a rare Friday that J.

wouldn't drop down with an evil glint in his eye that bespoke the presence

of "rocket fuel," ready for smoking, in his jacket pocket. And maybe C.

would stop by in a sexy mood, to drag me off for one of our occasional

bouts of casual slamming. Vancouver seems a long way away. Tired and thirsty,

I stop by a café across the street from La Concordia and slug back

four Poker beers in rapid succession. Then I weave my way through boisterous

early-evening streets, with salsa pounding from the rumbeaderos

up on Calle 25. I plant myself briefly at another dive, and down three

thimbles of aguardiente in quick sips. "You're drinking fast," the

proprietor says. "You must be from Germany." I'm walking fast, too - unsteadily

by now, but I feel enough artificial exuberance to dull the homesickness

and the failed explorations of the day. What next? A sidewalk tout hands

me a slip of paper: "BABILONIA. Multiple shows in erotic showers. Body

massages. Video show." Worth a look? But it's pathetic, a few business

types sipping overpriced beers as combination-hookers-and-strippers make

the rounds. Occasionally the music rises to an ear-shattering crescendo

and one of the girls does a bump-and-grind onstage, flinging off her clothes

and escaping as quickly as possible to the changing room.

Enough of this shit.

It's only just gone nine o'clock, but Friday night in Bogotá

is winding down, at least at street-level. The vendors are closing up their

stalls; a few straggling couples are hailing taxis; and the alcohol high

has worn off enough to make me realize I'm hungry. I walk for blocks trying

to find some sustenance; nothing's open, and I end up at the Super Perro

Suiza, a hot-dog stand near the Plaza Bolívar. I inhale two heavily-laden

dogs - odd dressings, including something like Kellogg's Frosted Flakes,

but palatable - and burp the last few blocks home. Lying on the bed at La

Concordia, a nightcap smoke just makes me feel wretched; the room spins

when I close my eyes.

Dizzy, dusty-mouthed sleep comes.

One last day in Bogotá. I wake without the splitting headache

I'd feared, and spend a leisurely morning, camera in hand, photographing

the busy Saturday street-life.

One side-expedition proves fruitless. Passing the new Congress building

a couple of days earlier, I'd had a good giggle at the sign posted at the

main entrance: FOR YOUR SECURITY, PLEASE DEPOSIT YOUR FIREARMS HERE. But

when I head over to take a snap, the sign has mysteriously disappeared:

there is only a patch of drying concrete. Someone, it seems, has decided

the message is out of keeping with "the new Colombia."

"The new nation," in fact, is all the rage as the country works to throw

off its unhappy international image. Even the police have gotten in on

the act, promising "a new era" free of the corruption and abuses of the

past. Change is the dominant theme in Colombia's presidential-election

fever - except that this is more of a mild flush than a fever. The main preoccupation

of the political class is to deal with the embarrassing dilemma of absenteeism,

which is predicted to surpass fifty percent in the national poll scheduled

for the end of May.

The general consensus in the press is that this year's voting will be

an exercise in controlled tedium. That is how many Colombians apparently

prefer it. The last round of presidential voting, in 1989 and 1990, was

anything but dull. It was also anything but peaceable. Four presidential

candidates were assassinated, including the projected winner, the Liberal

candidate Luis Carlos Galán. Galán was gunned down at Bogotá

airport in August 1989, presumably at the behest of the Medellín

cartel, whose organization he had vowed to eradicate. His death was a watershed,

"felt in Colombia much the same way that the killing of Benigno Aquino

was felt in the Philippines, or the murder of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro

was felt in Nicaragua," according to María Jimena Duzán.

The high-profile killing of a mainstream candidate overshadowed a much

more far-reaching and bloody campaign against the Unión Patriótica,

a coalition of leftist parties (including the Colombian Communist Party)

cobbled together by the FARC guerrillas during a brief truce worked out

with the administration of Belisario Betancur. The process, aimed at incorporating

the FARC into the civilian political process, soon foundered. The organization

remains the most active, and incidentally the wealthiest, of Colombia's

guerrilla groups, in large part thanks to its lucrative skimming of cocaine

profits in the areas it controls in the south and southwest of the country.

But the civilian coalition thrived, "successfully establish[ing] itself

as the country's third political force and main opposition party" (according

to Jenny Pearce); it won nearly five percent of the vote in the 1986 elections.

That immediately exposed the UP to the wrath of the right wing, furious

that a "guerrilla front" was permitted to contest national elections at

a time when the truce with the FARC had broken down and the rebels were

continuing their campaign of subversion in the countryside. A retired general,

Rafael Peña Ríos, voiced conservative and army concerns in

a widely-cited 1988 interview with El Tiempo. Asked, "Don't you

think that the [leftist] political groups are one thing and the guerrillas

another?," Peña Ríos responded: "The violence of the so-called

paramilitary groups [i.e., right-wing hit squads, often working in tandem

with the army and drug traffickers] comes from the transparent relationship

between political groups and guerrilla groups. It wouldn't have arisen

if from the beginning in the [peace] agreements the former were made responsible

for what the latter did."

Nearly two thousand UP members and leaders were exterminated in the

runup to the 1990 elections, and close to forty thousand other Colombians

died in the same period - most of them leftists slaughtered in perhaps the

worst paroxysm of state terror the country had ever seen.

After the carnage of the late '80s, the emphasis in the 1994 elections

has shifted to symbolism rather than substance. On a surface level, the

campaign has all the trappings of its correlates in the West. Bright billboards

are everywhere; there are upbeat radio jingles and TV spots, energetic

discussion in the press about the ostensible differences among the candidates.

But the bluster cannot disguise that this is very much a two-horse race,

as has been standard in Colombia since the advent of the modern party system

in the mid-nineteenth century. The problem is, the Liberal-Conservative

dyad has blurred so much over the years that it's often difficult to tell

who is riding which horse.

As in Lebanon, the most significant twentieth-century transformation

in the Colombian political system was the striking of a "National Pact"

aimed at ending (in Lebanon's case, forestalling) a debilitating civil

war. La Violencia, which began as a straightforward Liberal-Conservative

feud of the kind familiar to historians of Colombia and Latin America more

generally, had spiralled out of control. Not only was the country facing

economic and social breakdown, but a real threat of revolution had appeared

on the horizon. Peasant bands in the countryside were moving away from

their explicit Liberal or Conservative allegiances, and establishing power

bases of their own, becoming the de facto authority over large swaths of

rural Colombia. (The FARC guerrillas, for instance, date from this period.)

To avoid the collapse of an élite-run political system, Liberals

and Conservatives united in 1957. They agreed to support a single presidential

candidate, and to divide cabinet and state appointments equally for sixteen

years. Though formally abrogated in 1974, the agreement continued to structure

Colombian politics in reality until at least 1990. And it would be a dissenting

voice indeed that didn't consider the National Pact still the philosophical

bedrock of national political life. On one level, it has functioned smoothly,

preventing a renewed flaring of the Liberal-Conservative civil war and

allowing high levels of macroeconomic growth. On another, it has created

an ossified, noncompetitive political system that has excluded more than

it has incorporated. The high levels of absenteeism, along with the numerous

guerrilla groups and other non-state actors operating throughout the country, testify to popular disenchantment with a system based on cronyism

and the backroom divvying-up of the spoils.

In Ambalema, over a beer, I'd asked William - a young café employee - just what was going on. "It's hard for a foreigner to figure out. You have

Ernesto Samper the Liberal candidate, right? And Andrés Pastrana,

the Conservative. So how come I keep seeing 'Liberals for Andrés'

banners?"

William had smiled. "Look. Being Liberal or Conservative doesn't say

much about what you really believe. It's a matter of tradition. It depends

on the family you're born into. I was born a Liberal, for instance. What

you have these days is a lot of courting of support across traditional

political lines. Pastrana, for example - he's younger than Samper, so he's

going heavily after the youth vote, whether Conservative or Liberal."

Like Democrats-for-Reagan. And in fact, the U.S. political system, with

its entrenched two-party oscillations (the two branches, that is, of the

Capitalist Party), seems to parallel Colombia's closely.

The Liberal and Conservative platforms are strikingly similar. Jobs

(for). Corruption and narcotrafficking (against). Peace and reconciliation

(pro, with various caveats). A straw poll I've been conducting as I travel

the country has yet to turn up a single person who doubts the Liberal,

Samper, will emerge triumphant. ("As far as I'm concerned, he's the only

one who's not an outright thief and scoundrel," one woman had told me in

Cartagena.) Samper is playing the "kinder, gentler" angle for all he's worth,

promising a "social capitalism" that will accord a strong role to the state

in guaranteeing public welfare. Pastrana, a former TV journalist and mayor

of Bogotá who was briefly kidnapped by the Medellín cartel

in 1988, is pushing free enterprise, a tough line against guerrilla "assassins,"

and heavier punishments for "delinquents and terrorists." "I've presented

my candidacy as a multiparty movement," he tells El Espectador,

"in which people from every party or from no party can participate. Because

this is what corresponds to the new vision of Colombia."

Bringing up the rear is Antonio Navarro Wolff, a tall, ascetic-looking

former guerrilla leader, now presidential candidate for the M-19/Democratic

Alliance, which accepted the government's peace offer in 1990.(3)

Wolff now presents himself as the candidate of "the centre-Left," and rejects

accusations that he has sold out progressive forces in Colombia by joining

the civilian process - at a time when the other ex-guerrilla coalition, the

Unidad Patriótica, is being exposed to one of the most savage assassination

campaigns against an organized political force in hemispheric history.

"The Unión Patriótica was part of a project that advocated

the simultaneous pursuit of armed struggle and political struggle," Wolff

told Marc Chernick in November 1993. "This type of project is not viable

... We could either persist in a politics that was not viable and thus

forfeit the possibility of ever gaining power, or choose a path that was

more politically viable despite the inherent limitations." He, too, claims

to represent "a force for change."(4)

This year's campaign has not gone perfectly smoothly. There is the nagging

problem of generalized political apathy; UP members and leftist forces

more generally continue to be targeted; and, in late April, the treasurer

of Ernesto Samper's campaign in Antioquia department was killed. El

Tiempo's editorial comment on this last outrage was revealing. The

paper - a strong supporter of Samper - discounted suggestions that the killing

was politically motivated. It took pains to point out that "The campaign

for the presidency has developed more or less tranquilly, without acid

expressions or verbal aggressiveness from the participants, especially

[the major] candidates, who have tried to stay calm and avoid offensive

allusions and personal provocations." El Tiempo did take a stab

at one "well-known" figure in the Pastrana campaign (perhaps Pastrana himself?)

who had "seized every opportunity to return to this dangerous style of

politics," using "every error, suspicion, or rumour to launch attacks against

the Liberal candidate." Nonetheless, "nothing has happened that would imply

serious repercussions," such as political murder: this would threaten "the

internationally-recognized [!] democratic stability of the country." The

editorial closed with a plea for National Pact-style unity: "On May 30,

Liberals will open our arms to our ideological opponents, ready to forge

a better nation."

REJECT THE ELECTORAL FARCE - ABSTAIN. DON'T VOTE - STRUGGLE. If there

is any part of Bogotá that could be expected to embrace these sentiments,

it's the barrio popular on whose walls it is splashed.

Time, on this final day, to go looking for Bogotá's other face

- the south of the city, home to the bulk of the city's population, and the

destination of tens of thousands of poor migrants who flood annually into

this locus of perceived opportunity and upward mobility.

If I'd felt nervous about visiting Bogotá in the first place,

the prospect of busing out to the southern slums alone, and with no idea

precisely where I'm going, is even greater cause for anxiety. But I find

myself on Carrera 10 anyway, trying to choose among the dozens of busetas

streaming south. On an impulse, I hop a 689 circular route, and settle

myself by the window.

We roar a good thirty blocks south on Carrera 10, and the shanties come

into plain view to the southeast: a tangle of low-slung buildings, extending

to the very limits of settlement on Bogotá's southern fringe. There

are only green mountains beyond. I'm beginning to wonder whether the bus

will just do a U-turn at the end of the main thoroughfare, which so far

looks not much different from its more central and northern stretches.

But suddenly we are winding up to the left, and I begin to realize my arbitrary

choice of the 689 was an excellent one. The bus seems determined to traverse

every major road in these barrios, and I sit, glued to the window,

waiting - for what?

For a shantytown, I guess. You know: cardboard shacks, festering streets

choked with mud and ordure, pigs rummaging through the garbage. Children with torn T-shirts and runny noses. Barefoot women with hopeless

expressions. Men standing idly or menacingly by, or passed out on the sidewalks.

But it quickly becomes clear that Bogotá - at least in this broad

southeastern stretch - is very far from Managua, or Manila, or Port-au-Prince.

For one thing, the construction is sturdy: brick and concrete, densely-populated

but habitable. There is little in the way of jerry-built corrugated-iron

housing, except where a coop has been added to an existing roof. There's

certainly no one living in cardboard boxes or stacked sewage pipes. Many

of the dwellings, though simple, are tidy and brightly-painted; sidewalks

are no more litter-strewn than their downtown counterparts.

Yes, sidewalks. The roads here are mostly paved, right up to

the edge of most recent settlement. Even there, on this sporadically drizzly

afternoon, the streets are hardly a quagmire. Electrical lines are everywhere

in evidence, and it is the rare home that lacks a television aerial (even,

in a couple of instances, a satellite dish).

The people strolling past, or boarding the bus, seem well-dressed (who

am I to judge, with my soiled pants and three-day-old T-shirt?). Kids seem

healthy and well-fed. Not once in an hour-and-a-half of touring these slums

to their furthest periphery do I see a single example of the desperately

grimy street-life of downtown Bogotá. There's no-one sleeping in

doorways, no sooty urchins with heads buried in gasoline cans or pots of

glue.

Those people, of course, may be commuters from these very slums, headed

to where the opportunities for scavenging are greatest. But I don't think

so, somehow. There is too much determination and vivacity evident here.

The streets are alive with formal commerce: metalsmiths and car-repair

shops and sign-painters and corner-store proprietors. There is playful

mischief and good humour (one man runs out to pinch the bum of a friend

who's leaning into a car window, and retreats quickly, with an expression

of blithe innocence). There are plenty of smiles, even a couple for me

as I dismount at the end of the bus's route and hang around a few minutes,

licking a street-stall ice cream, before catching a bus home.

So what am I not seeing? A great deal, obviously. The grind of unemployment.

Crime - though I wonder how much more pervasive it is here than downtown,

given the vibrant community life everywhere on display. Alcoholism, domestic

violence, abandonment. The migrant's daily struggle to make ends meet in

unfamiliar and intimidating surroundings. But I feel confident in making

one vow: henceforth, I will expunge the word "slum" from my vocabulary

in describing these southern settlements. Barrios populares captures

the atmosphere perfectly. People's neighbourhoods. That's what these seem

to be, functioning and cohesive neighbourhoods, with one insuperable

advantage over other poor urban zones I've seen: they are full of Colombians,

who appear determined to undermine my pat stereotypes and suspicions at

every turn.

When I finally hop off the bus back at Avenida Jiménez, Bogotá

has gone all soft and mushy on me. The sprinkle of rain has subsided, and

downtown is aglow with late-afternoon sun that turns the buildings pink

and orange, and erects a magnificent rainbow high over the peak of Monserrate.

As an aside, has there ever been a presidential election in which, of

six candidates in total, four were assassinated (three from the UP alone),

while even the survivors could set off metal detectors with the ammunition

still in their bodies? Reading Jimena Duzán's firsthand description

of the 1990 elections, one has the sense that a journey through Colombia

a few years ago might have been a different and more frightful experience,

at least in the larger cities. Car-bombs in the streets were regular occurrences,

and levels of state terror and paramilitary activity were higher than in

1994. "The truth is that all of us who were still living felt like survivors

of a bloody war in which we lost the most important members of an entire

political generation. The majority of Colombian households had experienced

death close at hand. Mothers lost their children, brothers lost their cousins,

and cousins lost their best friends" (p. 255). Jimena Duzán lost

her sister, Sylvia, shot down while working on a British TV documentary

that dealt with narcotraffickers' involvement in the elections.

"Your war, understandable in its origins, now goes against the grain

of history. Today your standard tactics include kidnapping, coercion and

forced contributions, all of which are an abominable violation of human

rights. Terrorism, which you had always condemned as an illegitimate form

of revolutionary struggle, is today a daily recourse. Corruption, which

you also rejected in the past, has contaminated your own ranks through

your dealings with drug traffickers. ... It is time to search for a new

and innovative form of politics more in tune with the realities of today's

world. Your war, gentlemen, lost its historical significance long ago."

"It must be said that if certain practices and historical conceptions

have lost their historical significance, it is precisely the practice of

state terrorism and the systematic use of institutional mechanisms to assassinate

and 'disappear' political opposition. Such practices have converted despotism

into the natural form of governing." For the full text of the letters,

and the interview with Navarro Wolff, see Marc Chernick, "Is the Armed

Struggle Still Relevant?," NACLA Report on the Americas, 27: 4 (Jan./Feb.

1994), pp. 8-13.

The

state of emergency goes into effect on the evening of May 1st. No-one in

Bogotá pays much attention. It is, after all, the third suspension

of the constitution in the past two years, and it results in no noticeable

increase in the number of armed security personnel in the streets, nor

in the frequency of hands-against-the-wall body searches.

The

state of emergency goes into effect on the evening of May 1st. No-one in

Bogotá pays much attention. It is, after all, the third suspension

of the constitution in the past two years, and it results in no noticeable

increase in the number of armed security personnel in the streets, nor

in the frequency of hands-against-the-wall body searches.

adamj_jones@hotmail.com

adamj_jones@hotmail.com